Sign outside the Erie Canal Museum, Syracuse. Author’s photo.

WHISKEY AND THE “WEST”

We were forty miles from Albany

Forget it I never shall

What a terrible storm we had that night

On the E-ri-e Canal

O-o-oh the E-Ri-e was a-rising

The gin was a-getting low;

And I scarcely think

We’ll get a drink

Till we get to Buffalo-o-o

Till we get to Buffalo

—an old Erie Canal song

WHERE THE SPIRITS FLOWED: THE ERIE CANAL

Nothing in the nineteenth century did more to impact the growth of Upstate New York—and its burgeoning whiskey and spirits trade—than the Erie Canal. The canal itself linked Buffalo, on Lake Erie in the west, to Albany and the Hudson River in the east. When it opened in 1825, officials led by Governor DeWitt Clinton poured some Lake Erie water into the harbor at the mouth of the Hudson River, in New York City, in a ceremony marking the “wedding of the waters.”

Canal travel was made possible by water, but history shows the Erie was also well lubricated by whiskey. During the 1820s, as the canal was being dug, “America was reeling through the most phenomenal drinking binge in its history,” author Jack Kelly writes in Heaven’s Ditch: God, Gold and Murder on the Erie Canal, a 2016 account that explores the canal and the social upheavals of its time, including those related to drink, temperance and religion.

Sign outside the Erie Canal Museum, Syracuse. Author’s photo.

As we’ve seen, immigration, westward migration and the canal helped bring an end to the rum distilleries of Albany and elsewhere in New York. But that didn’t bring an end to distilling. Whiskey took over, partly because it was cheaper to make that spirit from the state’s own wheat and corn crops than to make rum from imported molasses.

That wasn’t the only economic benefit.

“Western farmers who grew barley, corn, and rye found it more profitable to ferment and distill their crops into strong liquor than to ship the grain to market,” Kelly writes. “Whiskey was plentiful and cheap.…By the middle of the decade [the 1820s], more than a thousand distillers were operating in New York state.”

It began even as the canal was under construction. Many independent contractors were engaged to dig sections, and they had to hire labor. “It was up to the contractor to hire the men to do the work,” according to The Erie Canal, a straightforward history written in 1964 by Ralph K. Andrist. “He was also expected to put up a shack big enough to sleep twenty-four to 40 men; to supply them with horses, capers, shovels and other equipment; to feed them and give them their daily ration of whiskey; and to pay them.”

Among the jobs on some canal-digging crews was a position called the “jigger boss,” Andrist notes. One canal contractor, a man named JJ McShane from Ireland’s County Tipperary, “paid a fair wage—75 cents a day—and provided a ‘jigger boss,’ a man who went along the line dispensing whiskey to the workers several times a day.”

Digging the canal was hard. “It was backbreaking work,” Andrist writes. “Every bit of dirt had to be dug up with picks and shovels from nearby fields and hills, and hauled by wheelbarrows and horse-drawn carts to the valley.” The contractors hiring workers had to make it sound a little more appealing. “‘Would you care for a fine job upstate?’ the hiring boss would ask Irish immigrants arriving in New York City. ‘Working conditions are very good, with roast beef guaranteed twice a day, regular whiskey rations and wages 80 cents.’”

Once the canal was completed, whiskey and other spirits took their place among the many goods shipped between Buffalo and Albany. “Boats from the west carried the produce of farm and forest to the cities of the East Coast: potatoes, apples, cider, wheat and milled flour, whiskey, live turkeys, lumber and precious furs,” Andrist writes.

And whiskey and distilled spirits were available along the route, Andrist’s account attests: “A captain could tie up in front of [canal-side shops] and buy a firkin—a small cask—of salt mackerel or a bushel of oats, have a horse shod or get a gallon of whiskey, and pick up the latest news at the same time. There was a grocery store, and sometimes two, at every lock—and in those days, they sold much more than food. Almost all of them carried liquor which, being very cheap, was drunk in great quantities.”

Passengers could drink their fill. In Heaven’s Ditch, Kelly writes of the delays that travelers endured during the many tedious stops the boats had to make when passing through locks. “During the wait, many passengers hop off the boat to stretch their legs. They can be pretty sure of a chance to grab a glass of whiskey. Locks are favorite spots for locals to set up small grocery shops that sell drinks and sundries.”

Temperance advocates were alarmed by the numbers, according to Kelly. “Reformers insisted in 1835 that there were some 1,500 drinking establishments along the canal, an astounding average of one every quarter mile. In Lockport [near Buffalo], two dozen bars crowded together within fifty feet of the locks.”

The Erie Canal Museum and Visitor’s Center, Syracuse. Author’s photo.

Over time, attitudes on all this drinking evolved. Early on, Andrist notes, “it was believed then [1825] that whiskey helped ward off the combination of fever and chills,” which was just one of the reasons whiskey was supplied to canal diggers and boat crews.

But the temperance movement gained traction as the nineteenth century wore on. “Frequent drunkenness led to violence aboard the boats, which spilled over into the towns,” Andrist writes. He continues:

So flawed was the Erie Canal by immorality that many began to refer to it as the “Big Ditch of Iniquity.” Believing the moral decline was a result of excessive drinking, New York canal commissioners tried in 1833 to prohibit liquor use by canal workers, but it was impossible to enforce. At least one company of canal boat owners announced that they would employ only “men who do not swear nor drink ardent spirits.”

Eventually, the growing temperance movement spurred the drive that led to Prohibition in 1919. In the meantime, however, both the production and consumption of alcohol continued in Upstate New York and elsewhere.

COCKTAILS ALONG THE ERIE TODAY

The “old” Erie Canal—and much of the original route—had ceased operations by the early twentieth century. It was replaced by the larger, more efficient New York State Barge Canal, which combined some older sections with new wider, straighter and deeper ones. In some cases, old sections remain as sleepy backwaters or quiet parks, while others have been filled in.

One of the filled-in sections is the stretch now called Erie Boulevard, running through Syracuse and its suburbs. That’s where Jeremy Hammill, a modern mixologist, creates and mixes cocktails at the Scotch ’n Sirloin, a restaurant and steakhouse on Erie Boulevard East, in the Syracuse suburb of DeWitt. He and a friend, Scott Murray, also run a small company manufacturing cocktail bitters, called Mad Fellows.

Among the drinks on Hammill’s cocktail list at the Scotch ’n Sirloin is one he called the Erie Boulevardier, a spin on the classic Boulevardier. A Boulevardier is a combination of bourbon, red vermouth and Campari or other Italian bitter liqueur. (It’s similar to a Negroni, which uses gin instead of bourbon.)

A Mule Named Sal, an Erie Canal–themed cocktail by bartender Jeremy Hammill, at the Erie Canal Museum in Syracuse. Photo by Dennis Nett.

We asked Hammill to create a couple of Erie Canal–themed drinks for this book. For our photos, he mixed them up at the replica nineteenth-century bar in the Erie Canal Museum, which sits along Erie Boulevard in downtown Syracuse. The museum features a replica packet boat and many period items and exhibits and is located in a former Erie Canal “weighlock,” where boats would put in to have their cargos weighed.

Here are Hammill’s Erie Canal cocktails. Each uses exclusively Upstate New York ingredients.

A Mule Named Sal

From Jeremy Hammill of the Scotch ’n Sirloin, DeWitt

1½ ounces 1911 Established Vodka

1 dropper of Mad Fellows Spiced Apple Bitters (or a splash of fresh-pressed cider)

Saranac Ginger Beer

A Cortland apple for garnish

Fill a Moscow Mule cup (a small copper cup with a handle) with ice. Pour in vodka and then add the bitters or cider. Top with ginger beer. Garnish with apple.

The Low Bridge, an Erie Canal–themed cocktail created by bartender Jeremy Hammill that uses all New York ingredients, at the Erie Canal Museum in Syracuse. Photo by Dennis Nett.

Low Bridge

From Jeremy Hammill of the Scotch ’n Sirloin, DeWitt

1 ounce Albany Distilling Death Wish coffee vodka

1 ounce Black Button 4 Grain Bourbon

1 ounce cinnamon/clove infused simple syrup (note)

1 dropper of Mad Fellows Mulled Spice bitters

½ ounce heavy cream

Freshly grated cinnamon

Chill a martini glass or coupe. Fill a shaker glass with ice and then add all ingredients except the cinnamon. Shake well and strain into martini glass or coupe. Sprinkle on cinnamon for garnish.

Note: To make the simple syrup, boil 2 cups water with 1 broken up cinnamon stick and 4 whole cloves to extract the flavor. When it smells right, add 2 cups sugar and boil to dissolve. Let cool and strain into a clean bottle. Will hold for a month in the refrigerator. (It can be reduced, but always use equal parts water and sugar.)

TEMPERANCE, TAXES AND “FIERY STUFF”

Rum distilling, which had thrived in Albany and the Hudson Valley in eastern New York in the 1700s, faded by the early 1800s. But thanks in large part to the Erie Canal and other westward trails, distilling of other spirits continued across Upstate New York, moving west along with the onrush of new settlers who built communities out of the wilderness.

“It was recorded in 1810 that Onondaga County had two breweries,” according to a 1997 pamphlet titled “Bottoms Up!” from the Onondaga Historical Association in Syracuse. “The average price for their product was $.17 per gallon and together they turned out about 7,200 gallons that year. It was a relatively minor enterprise, when compared to the 26 liquor distilleries in the county which produced nearly 80,000 gallons annually. Liquor sold at an average of $.80 per gallon!”

That scenario didn’t last, as breweries eventually overtook distilleries through the nineteenth century. The influx of German, Irish and other immigrants had something to do with that, but so did the rise of the temperance movement, as liquor was considered more evil than beer. Still, the distilled spirits industry did thrive. The rise of distilling took place all across Upstate New York, from the Hudson Valley west to the Great Lakes and up toward Canada.

It would be difficult to provide a record of every settler who set up a still or every entrepreneur who started a distilling business in Upstate New York. To provide a glimpse of how the distilling industry did emerge in the region, we’ll take a close look at one community: Skaneateles, a small village in Onondaga County, and the self-described “eastern gateway to the Finger Lakes.”

For this glimpse into distilling history we are indebted to Kihm Winship, a copywriter for a Skaneateles ad agency, who is also a local historian and a pioneering American beer and drinks writer. His research into distilling in and around Skaneateles is recorded in a WordPress blog entry he posted in 2011 called “Skaneateles Whiskey.”

Skaneateles is centrally located in New York and is on a major waterway (Skaneateles Lake). The lake feeds an outlet that turns into Skaneateles Creek, which descends through surrounding hills with enough force to power gristmills. The mills, back in the days before electricity and other modern energy sources, used water power to grind the grains that were grown in abundance on surrounding farm fields.

Grain and water—two major ingredients in distilled spirits—were plentiful. “Distilling was, not surprisingly, one of the first industries to accompany the settlement of Skaneateles,” Winship writes. And, he points out, distilling, like brewing, had another benefit for rural, farm-based communities like Skaneateles—the spent grain from the process was used to feed cattle, pigs and other livestock.

“Skaneateles whiskey was not sold by the bottle,” Winship writes. “If you wanted whiskey, you brought your own gallon jug to the seller, who might be the distiller or a merchant. In 1825, a gallon of whiskey cost 38 cents. And you could buy whiskey by the drink in a tavern or saloon. The earliest Skaneateles distilleries served the immediate area; the later distilleries were huge operations that sold the majority of their product elsewhere, shipping barrels by rail and the Erie Canal.”

Winship researched and found tales to tell about roughly a dozen Skaneateles distilleries that operated during the nineteenth century. (Keep in mind, Skaneateles has never been more than a small village of a few hundred or thousand residents). Here’s a sampling:

ROBERT & JONAS EARLL DISTILLERY. In 1802, Revolutionary War veteran Robert Earll and his brother Jonas Earll built and operated what appears to have been the area’s first distillery, north of the lake and near, but not directly on, Skaneateles Creek. “Using six bushels of wheat a day, the distillery’s daily output was 12 gallons of whiskey, which sold for 75 cents a gallon,” Winship writes.

WINSTON DAY DISTILLERY. Winston Day appears to have opened his distillery on the creek sometime before 1806. He had been a business partner of Isaac Sherwood, who founded an inn in the village that still stands today, the Sherwood Inn. Celebrated local artist John D. Barrow, Winship discovered, wrote this in 1876 about Winston Day’s product: “It was very fiery stuff…but from local patriotism and pride some of the townsmen confessed that they felt it their duty to learn to love it.”

EARLL, TALLMAN & CO., AKA EARLLS & TALLMAN DISTILLERY. This distillery was open from 1857 to 1882, according to Winship’s research. It was one of several run by family and descendants of Robert Earll and located along Skaneateles Creek near Mottville. “This distillery was by far the largest and most lucrative industry in Skaneateles,” Winship writes. In 1882, the distillery was purchased and converted into a paper mill—a fate shared by several of the Skaneateles whiskey makers.

HEZEKIAH EARLL & CO. DISTILLERY AKA HART LOT DISTILLERY AKA EARLL BROTHERS DISTILLERY. This late nineteenth-century distiller was an Earll enterprise with more partners, at Hart Lot north of the village. Its story offers this little Civil War–era economics lesson: “In 1862, to pay for the Civil War…Congress passed and President Lincoln signed the Tax Act of 1862, which included a tax on all whiskey manufactured after the first day of July 1st,” Winship writes. “Every distillery in the country, including the Earll distillery, knowing when the law would go into effect, ran day and night until the last hour of June 30th, accumulating a large stock of whiskey, which at midnight rose in value, netting Hezekiah Earll’s sons thousands and thousands of dollars.”

Near Skaneateles, Winship found records for another distillery, CARPENTER’S DISTILLERY, in New Hope (Cayuga County). This one, operating between 1834 and 1875, was one of many businesses using the water power generated by Bear Swamp Creek as it flowed down to Skaneateles Lake. John H. Carpenter bought out a partner in 1844 and added a gristmill and a sawmill. In 1855, the distillery, at the hamlet of New Hope in the town of Niles, used twelve thousand bushels of grain, produced 550 barrels of whiskey and fattened eighty-five hogs with the spent mash.

Winship uses Carpenter’s experience to illustrate the rise of the anti-alcohol temperance movement. In this case, he found, Carpenter had “incurred the wrath” of Thurlow Weed Brown (1819–1866), a temperance advocate who edited and published the Cayuga Chief in nearby Auburn. Brown frequently wrote of Carpenter and the evils of his distillery, using what Winship calls “impassioned prose.” In one case, according to Winship, Brown recorded the death of a man whose corpse was found next to a jug of Carpenter’s whiskey.

“Carpenter knew the deceased was under the influence of liquor when at the distillery, and also knew that he had a wife and a large family of children at home,” Brown wrote in a piece called “Murder in Niles” in the Cayuga Chief on May 21, 1851. “He knew another thing, notwithstanding he swills liquor himself, or his barefaced swearing. He let his victim have his liquor and then over the corpse of the man his whiskey killed swears before God that he thought it would do him good for ‘mornings use’!”

Taxes and temperance were the twin killers of the small distilleries in Skaneateles and elsewhere in Upstate New York. “Two factors ended the run of distilleries in Skaneateles. First, safer drinking water and the success of the Temperance movement led to people drinking less whiskey,” Winship notes before he lists the accumulating taxes the whiskey makers faced. “Most distillers couldn’t wait to get into another line of work.”

SMALL-BATCH DISTILLING COMES HOME

It took more than one hundred years for distilling to return to Skaneateles and other small, out-of-the-way towns in the heartland of Upstate New York. We’ll get into the story of how the modern resurgence of distilling in Upstate New York came about in a later chapter.

In the meantime, let’s look at three of the twenty-first-century distilleries operating in the smaller towns of central New York State. They’re the modern equivalent of those small, family-owned distilleries found in Skaneateles and elsewhere in the nineteenth century. These three distilleries embody the spirit of those early spirits makers.

Last Shot Distillery, Skaneateles

In the summer of 2016, distiller Chris Uyehara proudly set a small oak barrel on the bar of the Last Shot Distillery just outside the village of Skaneateles. He inscribed these words on the barrel head: “First barrelled whiskey in Onondaga County since Prohibition.”

Uyehara knows his history. He and his partners, building owner John Menapace and John’s daughter Kate (the tasting room manager), opened Last Shot in late 2015 on the spot once occupied by the Earll & Kellogg Distillery, on Skaneateles Creek. “We’re bringing distilling home to its roots,” Uyehara said.

Like many small distillers, Last Shot started with clear or white spirits, including a vodka made from corn and wheat, a moonshine made from corn and a white whiskey called Lightning. (Lightning is both a traditional name for unaged whiskey and the name of a line of sailboats once manufactured on the distillery site.)

Uyehara, a noted local chef, culinary instructor at Syracuse University and a world-class ice carver, also immediately put in motion some aged whiskeys, including a bourbon made from the same mash bill (grains) as the Lightning. That’s the whiskey launched in that barrel in the summer of 2016.

Last Shot also makes two spirits distilled from maple syrup, a plentiful local product in the area. One is an unaged White Maple, and the other is Sweet Maple, aged briefly on oak staves and dosed with a shot of syrup at the end for flavor and sweetness.

In 2017, Uyehara introduced a “distiller’s reserve,” or limited batch whiskey, called Last Shot American Whiskey. It’s made with corn, wheat and triticale, a member of the wheat family that tastes a little like rye. The American Whiskey is aged in Last Shot’s used bourbon barrels, so it soaks up some of the honey and floral aromas from that spirit.

The first barrel of aged whiskey made in Onondaga County since Prohibition, released in June 2016 at the Last Shot Distillery in Skaneateles. Author’s photo.

The Lightning Mule, a cocktail made with Lightning (unaged) Whiskey at Last Shot Distillery in Skaneateles. Author’s photo.

Here’s a cocktail served in the Last Shot tasting room and made with its Lightning Whiskey.

Lightning Mule

From Last Shot Distillery, Skaneateles

1½ ounces Last Shot Lightning Whiskey

½ ounce fresh squeezed lemon juice

4 ounces ginger beer

Slice of ginger

Lime wedge

Put whiskey and lemon juice into ice-filled glass, top with ginger beer and stir. Garnish with a slice of ginger and a lime wedge.

Old Home Distillers, Lebanon

Lebanon is a small town that is also the geographic center of New York State. It’s close to where the Carvell brothers, Adam and Aaron, grew up.

Both brothers had moved on from their small-town roots in Central New York and found jobs in the drinks and hospitality business elsewhere. Adam Carvell pursued a law degree before deciding it would be more fun to run a bar in Tucson, Arizona. Aaron Carvell had a career in beverage and wine marketing in San Francisco before entering the hospitality industry in New Zealand.

They’re still in the drinks business. Only now they’re based in Lebanon, where they’re running Old Home Distillers, producing whiskey, gin and more. The chance to run the distillery with their mom and dad lured them back home, and Old Home Distillers opened in late 2015.

The idea to open a craft distillery started with Adam Carvell. “I was in the bar business and so I knew small, craft distilling was really picking up,” he said. “And I knew it was something we could do here. I knew it was getting big in New York state.”

The location they picked is a former “gentleman’s horse farm” on Campbell Road, south of Lebanon and close to the little crossroads called South Lebanon. The old tack room is the tasting room, and the still and production area is set up in what had been a horse barn.

Adam Carvell (left) and his brother, Aaron, owners and distillers at Old Home Distillers in Lebanon, New York. Author’s photo.

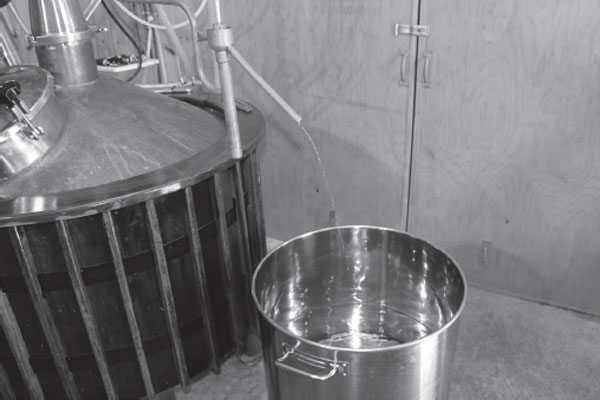

The still in action at Old Home Distillers, Lebanon. Author’s photo.

Their research led them to stories of the small distilleries once set up in the region. A local historian, Stan Roe, shared a story of a nineteenth-century distillery located in a barn not far from the current Old Home site. It used both potatoes and grain to make spirits. A member of the family born in 1852 remembered hearing “his mother tell of men walking down over the hills in the evening for whiskey.”

Today, Old Home Distillers has clear spirits, including a corn whiskey, gin and applejack in addition to a flavored maple whiskey and a pumpkin-spiced whiskey, plus two aged bourbons and a single-malt whiskey, made from barley.

The Carvell brothers like to experiment while staying within the spirits-making tradition. They’re both beer lovers and dream, for example, of distilling a hoppy India Pale Ale into a new type of spirit.

“We don’t want to just make whiskey, gin and vodka,” Adam Carvell said. “We want to bring something creative to the process.”

Makers of 100 percent barley malt whiskey were relatively rare in the first decade or so of the distilling renaissance in Upstate New York, in part because barley growers and malt houses are few and there is competition for the product with brewers. Here’s a cocktail made with Old Home’s Single Malt Whiskey (a nod to single-malt scotch):

Burns Night in America

From Old Home Distillers, Lebanon

Absinthe (or absinthe substitute) for rinse

2 ounces Old Home Single Malt Whiskey

½ ounce sweet vermouth

Dash of Angostura bitters

In a chilled cocktail glass, add a few dashes of absinthe, swirling around to coat the glass, and then discard excess. Combine whiskey, vermouth and bitters in a ice-filled shaker; shake and strain into the glass.

Brothers John and Joe Myer trace their family way back in the history of the town of Ovid, centrally located in Seneca County, the heart of the Finger Lakes.

Some of their ancestors helped found the town in 1789, and one, Andrew Dunlap, is credited with being the first person to plow land in what is today Seneca County. As early as 1810, some members of the family were operating distilleries, making hard liquor out of the grains available in the local countryside: rye, wheat, corn, barley and oats.

Today, John Myer is a farmer, raising many of the same crops in the old-fashioned way, that is, organically. Joe Myer is a former dairy manager, an expert on animal husbandry and a painter, musician and poet.

In 2012, John and Joe opened Myer Farm Distillers in the heart of the Finger Lakes and in the midst of a vibrant winery region. Like the many wineries that sit among the vineyards that supply their grapes, Myer Farm Distillers sits amid the corn and wheat fields that form the base of its spirits. The tasting room is well positioned along the wine trail for those seeking an alternative beverage or two.

Joe Myer in the barrel room at Myer Farm Distillers in Ovid, Seneca County. Author’s photo.

The Bourbon & Cherry, a cocktail made with John Myer Bourbon Whiskey at Myer Farm Distillers in Ovid. Author’s photo.

“We had a farm and the farm background,” Joe Myer said. “We saw the growth in craft distilling and realized what a perfect opportunity we had to do that together.” And, he added about his own decision to return to the farm, “It’s hard to get away when it’s in your blood.”

Myer Farm makes a wide array of spirits, from vodkas (including flavored versions), gins, aged and unaged whiskeys and flavored specialty spirits, including honey, cinnamon and ginger.

The farm is about nine hundred acres, and some 12 to 15 percent of its yield is used by the distillery. The brothers put the philosophy on their website: “At Myer Farm Distillers, we both plant the seed and produce the spirit.”

Myer Farm rotates its tasting room cocktail selection frequently. Here are some examples.

Bourbon & Cherry

From Myer Farm Distillers

1½ ounces John Myer Bourbon Whiskey

Cherry juice

Bitters, to taste

Orange wedge

Fill a rocks glass with ice. Add whiskey, top with cherry juice. Stir in bitters to taste. Garnish with an orange wedge.

Peach on the Beach

From Myer Farm Distillers

1½ ounces Cayuga Gold barrel-aged gin

1 ounce pineapple juice

1 ounce orange juice

1 ounce White Peach Daiquiri Mix (or peach puree)

Maraschino cherry

Shake all ingredients with ice and strain into martini glass. Drop a stemless maraschino cherry into glass.

Drawing of Hustler’s Tavern in Lewiston, which some believe was the birthplace of the cocktail. Lewiston Council on the Arts.

“Hudson” Mint Julep and Bittered Sling with Rum, two cocktails created by Jori Jayne Emde at Fish & Game. They were inspired by the first definition of the cocktail. Author’s photo.

The Pineapple Upside Down Cake at Water Street Landing, Lewiston. Blue Chair Bay Rum is bottled in Rochester. Author’s photo.

Four Grain Bourbon, from Black Button Distilling in Rochester. Author’s photo.

The Doctor Cocktail, made with Quackenbush Still House Albany Amber Rum, from Albany Distilling Company. OE Pro Photography for Albany Distilling Company.

The Nonny Jack Cocktail from the Cocktail Grove at Hudson Valley Distillers, Clermont. Author’s photo.

Bartender Jeremy Hammill of the Scotch ’n Sirloin in DeWitt mixes a cocktail he created called the Low Bridge at the Erie Canal Museum in Syracuse. Photo by Dennis Nett.

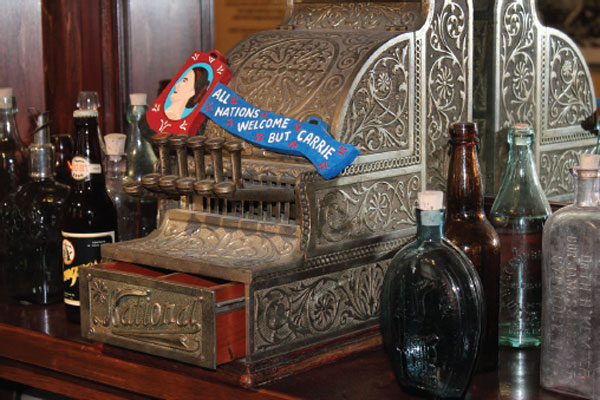

An antique cash register behind the bar at the Erie Canal Museum in Syracuse, with a sign poking fun at nineteenth-century temperance activist Carrie Nation. Author’s photo.

Distiller and co-owner Chris Uyehara at Last Shot Distillery in Skaneateles. Author’s photo.

A selection of the spirits offered at Old Home Distillers in Lebanon, New York, including corn whiskey, applejack, maple whiskey, malt whiskey and gin. Author’s photo.

Cocktails at Myer Farm Distillers in Ovid, Seneca County. Author’s photo.

Tom & Jerry drinks at the Crystal Restaurant in Watertown, where they are a holiday season tradition. Author’s photo.

Serving Tom & Jerrys from an antique punch bowl at the Crystal Restaurant in Watertown. The drinks are a holiday tradition at the Crystal. Author’s photo.

The Saratoga Sunrise Cocktail at the Travers Bar at Saratoga Race Course, Saratoga Springs. Author’s photo.

The Mamie Taylor, named for a renowned Broadway star, was one of the most popular cocktails at the turn of the twentieth century. Author’s photo.

The Cooperstown Cocktail, a pre-Prohibition drink, as made at the Otesaga Hotel in Cooperstown. Author’s photo.

The Not a PFD cocktail at the Channelside Restaurant overlooking the St. Lawrence River in Clayton, made with Clayton Distillery Bourbon. Author’s photo.

Bitters on the bottling line at Fee Brothers in Rochester. The company makes bitters, cordials and other cocktail ingredients. Author’s photo.

The Flaming Rum Punch, made at the Gould Hotel in Seneca Falls. The town becomes “Bedford Falls” each holiday season in honor of the movie It’s a Wonderful Life. Author’s photo.

The Mapple Jack Moonrise, a cocktail at the American Hotel in Sharon Springs. Author’s photo.

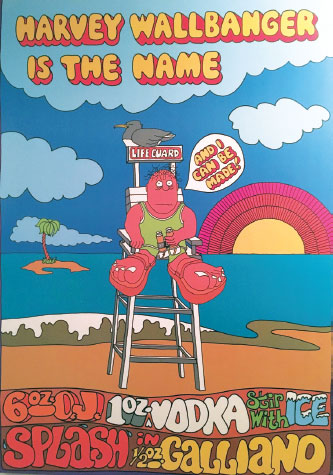

A 1970s poster created by William J. “Bill” Young, who came up with the ad campaign for the Harvey Wallbanger cocktail. Courtesy of Will Young.

A neon cocktail sign in the tasting room at Finger Lakes Distilling, in Burdett. Author’s photo.

The Hot Chai-der cocktail at 1911 Established (Beak and Skiff Orchards), LaFayette. Author’s photo.

Brian McKenzie, president of Finger Lakes Distilling Company in Burdett. The distillery overlooks Seneca Lake. Author’s photo.

The White Pike Mojito, at the Finger Lakes Distilling Company. Author’s photo.

The 585 Cocktail at Black Button Distilling in Rochester, made with the distillery’s gin and Bourbon Cream and Fee Brothers Orange Bitters. Author’s photo.

Spirits produced at Lockhouse Distilling in Buffalo, including a coffee liqueur, Ibisco Bitter, gins and vodkas. Author’s photo.

The What She’s Having cocktail, from Lockhouse Distillery in Buffalo, made with the distillery’s Ibisco Bitter. Author’s photo.

A patron having a tiki cocktail in a coconut at the Ox & Stone bar during the 2016 Rochester Cocktail Revival. Photo by Katrina Tulloch, NYup.com.

The Romancing the Stone cocktail in the Turquoise Tiger lounge at the Turning Stone Resort Casino in Verona. Author’s photo.

Ben Reilley, of the Life of Reilley Distilling Company in Cazenovia, with his DiscoLemonade, New York State’s first “cocktail in a can.” Author’s photo.

The New York State Fair Bloody Mary at the Empire Room patio on the state fairgrounds during the 2016 New York State Fair. Author’s photo.