Tools of the trade for a nineteenth-century bar at the Erie Canal Museum in Syracuse. Author’s photo.

THE “PROFESSOR” AND THE COCKTAIL

THE BARTENDER TURNS PROFESSIONAL

For much of the early to mid-nineteenth century, bars and saloons—and the drinks consumed in them—were on the seedy side of society. You’ve seen the movies where the cowboy walks into the saloon and gets a quick shot of whiskey or a beer—or both. It was true in the Wild West, but also in parts of the East, like Upstate New York.

“In the 1800s, the saloons thrived because the factory workers, the guys who did dangerous grunt work, had them as the places where they could go to relax—sort of like the modern man-caves,” said Dennis Connors, curator of history at the Onondaga Historical Association in Syracuse. In 2014, Connors created an exhibit called “Culture of the Cocktail Hour” at the museum using artifacts from two centuries of Syracuse drinking history.

Drinks author William Grimes, in Straight Up or On the Rocks, notes that things were starting to change just before and during the Civil War. It was the time of the creation of a new profession in society: the bartender. Grimes traces the origins of the term to about 1836. At some point during the nineteenth century, the bartender changed from the fellow who slid the beer glass down the bar to someone who might be able to mix you a decent cocktail.

“The mixing of a cocktail was a matter for professionals,” Grimes writes. “A man would no sooner shake one up himself than cut his own hair or bake his own souffle.” And no one did more to change that image than a son of Upstate New York: “The Professor,” Jerry Thomas.

Tools of the trade for a nineteenth-century bar at the Erie Canal Museum in Syracuse. Author’s photo.

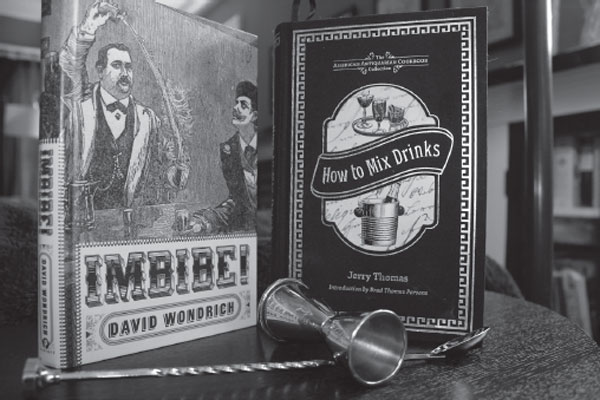

Bar books: a reprint of Jerry Thomas’s How to Mix Drinks (1862) and Imbibe!, the 2007 biography of the celebrated bartender by cocktail historian David Wondrich. Author’s photo.

He made his name in locales like San Francisco, St. Louis, New Orleans, Chicago and New York City—all the drinking and sporting capitals of nineteenth-century America.

He was the world’s first “celebrity” bartender, earning the nickname “The Professor” for his wizardry in concocting creative cocktails. He’s credited with inventing (or at least popularizing) many of the classic drinks we know today, along with some long-forgotten libations. He compiled the first book of cocktail recipes ever printed, in 1862.

He was as much a showman as a mixologist, celebrated around the world.

Jerry Thomas was born and raised in Upstate New York. His hometown is Sackets Harbor, located on the often frosty shores of Lake Ontario, just west of Watertown in northern New York. Sackets is an old military town and was the scene of an important naval battle in the War of 1812. A young Ulysses S. Grant was once stationed at the army barracks in Sackets Harbor.

Thomas achieved considerable fame in the mid-1800s—but not for military action or for the other usual paths of that era, like holding political office, writing novels or performing in the theater. His initial renown came from knowing his way around a bar. He wielded a bar spoon, with mixing glasses at hand and bottles of spirits and flavorings at the ready.

During Prohibition, author Herbert Asbury, a frequent (but not always reliable) chronicler of colorful American history, wrote this description of the Professor:

[He]was an imposing and lordly figure of a man…portly, sleek and jovial, and yet possessed of immense dignity. A jacket of pure and spotless white encased his great bulk, and a huge and handsome mustache, neatly trimmed in the arresting style called walrus, adorned his lip and lay caressingly athwart his plump and rosy cheeks. He presented an inspiring spectacle as he leaned upon the polished mahogany of his bar, amid the gleam of polished silver and cut glass, and impressively pronounced the immemorial greeting, “What will it be, gentlemen?”

When Thomas mixed many of his drinks, he put on a show. To make his famous Blue Blazer concoction, for example, Thomas lit whiskey on fire and then mixed or “rolled” it from glass to glass in a pyrotechnic performance behind the bar.

“Like Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone and Buffalo Bill Cody, he was the sort of self-invented, semi-mythic figure that America seemed to spawn in great numbers during its rude adolescence,” William Grimes wrote in a 2007 New York Times story titled “The Bartender Who Started It All.”

Grimes’s newspaper account of Thomas’s life also marked the publication of a book by fellow cocktail historian David Wondrich. Imbibe!, as noted earlier, tells the story of nineteenth-century cocktails and cocktail culture through the lens of Jerry Thomas’s life and career. The subtitle expounds upon that journey: “From Absinthe Cocktail to Whiskey Smash, a Salute in Stories and Drinks to ‘Professor’ Jerry Thomas, Pioneer of the American Bar.”

Even a seasoned historian like Wondrich had trouble tracking down details of Thomas’s life before he left Sackets Harbor. The future bar star seems to have been born in 1829 or 1830, the son of Jeremiah and Mary Morris Thomas, about whom “we know nothing,” Wondrich says. There is evidence he had a brother named George M. Thomas because there are business records showing they ran saloons together at some point.

“His early childhood is a blank,” Wondrich writes. “We can deduce that his social class wasn’t the highest, but only from his career choices.” (Being a barman in the 1800s was not the way to a spot on the Social Register.) According to one obituary, Thomas started his bar career at age sixteen in New Haven, Connecticut. It’s not clear how or when he got there.

“New Haven, which was both a seaport and a college town, would have been an excellent place to pick up the rudiments of the [bar] craft,” Wondrich writes in Imbibe! “In 1846, though, it was a craft still transmitted by long apprenticeship, and his duties in the bar would far more likely have included sweeping, polishing, and carrying than mixing fancy drinks for customers.”

He later shipped out as a sailor before returning to bar work, initially in the California Gold Rush. He may also have done some prospecting. His career eventually took him to New York City, where he ran a series of bars before going broke.

His death, in December 1885, merited a news obituary in the New York Times under the heading “In and About the City. A Noted Saloon Keeper Dead.” The account read, “‘Jerry Thomas’ as he was familiarly called, was at one time better known to club men and men about town than any other bartender in this city, and he was very popular among all classes.”

“Jerry was of an inventive turn of mind and was constantly originating new combinations of drinks,” the obituary continued, noting especially his claim to have invented the Tom & Jerry, an egg-based warming winter drink he named for himself. (We’ll have more on that drink—and Thomas’s dubious claim to be its inventor—later.)

If he didn’t invent all the drinks he claimed, he was at least responsible for the first book that collected recipes and techniques. The book had multiple editions, including a noteworthy 1887 revision. It was published under several names, such as How to Mix Drinks, The Bartender’s Guide and, most colorfully, The Bon Vivant’s Companion.

“So rapturously was The Bon Vivant’s Companion acclaimed, and so phenomenal its success, that scores of imitations soon appeared, and the book-stalls of the nation groaned beneath the weight of volumes purporting to give directions for the concocting of all sorts of delectable beverages,” wrote Asbury in a piece for the American Mercury during the height of Prohibition, in December 1927. “But through all this excess of publishing Professor Thomas’s work remained steadfastly first in the hearts of his countrymen, everywhere accepted as the production of a Great Master.”

Asbury, best known today as the author of The Gangs of New York, wrote the introduction that appears on the 1887 edition of Thomas’s book. It should be noted that Asbury wrote in extraordinarily purple prose and had little command of facts. He reports, for example, that Thomas was born in New Haven, when that is not the case.

If, during his illustrious career, Jerry Thomas ever used his Upstate boyhood for inspiration in creating drinks, there is no sure evidence. Given his renown, however, you will find various Thomas recipes sprinkled throughout this book.

Scouring his work for Upstate-specific drinks yields a few possibilities. One is called the Knickerbocker, a drink that takes its name from a word used to describe the early Dutch settlers in New York State.

Knickerbocker

From How to Mix Drinks, by Jerry Thomas

1 lime or small lemon

3 teaspoons raspberry syrup

1 wineglass Santa Cruz rum

3 dashes Curacao

Squeeze out the juice of the lime or lemon into a small glass; add the rind and the other materials. Fill the glass one-third full of fine ice, shake up well and strain into a cocktail glass. If not sufficiently sweet, add a little more syrup.

Another drink, in the 1887 update, uses Catawba, a popular red wine made from a native North American grape produced in great quantities in Upstate’s Finger Lakes and other wine regions in the nineteenth century.

Catawba Cobbler

From The Bartender’s Guide, by Jerry Thomas

1 teaspoon fine white sugar, dissolved in a little water

1 orange slice, cut into quarters.

Catawba wine

Seasonal berries

Fill a large bar glass half full of shaved ice, sugar and orange and then top with Catawba wine. Ornament the top with berries in season and serve with a straw.

THE LEGACY OF JERRY THOMAS

In the 1920s, Herbert Asbury wrote of Thomas’s work, “Even to this day the real adept at manipulating a cocktail-shaker and other such utensils, one who approaches the act of compounding a drink in the proper humbleness of spirit, regards it [Thomas’s The Bon Vivant’s Companion] somewhat as the Modernist regards the Scriptures: as perhaps a trifle out-moded by later discoveries, yet still worthy of all respect and reverence as the foundation of his creed and practice.”

In the 1990s and early 2000s, when classic cocktails were “rediscovered” and the art of mixing drinks began its resurgence, the “Scriptures” of Jerry Thomas once again found fame. Many of the mixologists and drinks writers who promoted the return of cocktail culture in America paid homage to Thomas.

In 2003, Robert Hess, who runs the influential cocktail website DrinkBoy.com, wrote a tribute to Thomas. It came on the occasion of a gathering of modern cocktail celebrities at the Plaza Hotel in New York City in which each created a drink from Thomas’s catalogue: “Bartenders world-wide owe a debt of gratitude to Jerry Thomas, but unfortunately few modern bartenders know anything about him,” Hess wrote. “Jerry Thomas is considered to be the Father of the Cocktail. This is not to say that he invented it, which he did not, but instead that he nurtured it, raised it, and in turn helped to introduce it to the world around him. By profession he was a bartender, and by reputation he was a showman. A combination of skills that we still see in place today behind many bars.”

It was Thomas’s work, Hess notes, that helped bring the cocktail to the forefront ahead of other mixed drinks. The 1862 book, Hess writes, “was the first recipe book for bartenders, as well as the first book to include recipes for the drink known as the ‘cocktail,’” though there were just ten of those in that edition. “Clearly they were just one style, among many other drinks that a bartender was expected to prepare. In later editions of this book, Mr. Thomas would double this count to a full twenty, as well as move it to the front of the book. Clearly the cocktail was building up steam, and Jerry Thomas was right there at the head of the train.”

Here’s a Jerry Thomas classic, as presented in April 2003 at that modern mixologist gathering at New York City’s Plaza Hotel.

Blue Blazer

As Presented by Dale DeGroff

1½ ounces Talisker Scotch whiskey, warmed

1½ ounce boiling water

¼ ounce simple syrup

Lemon peel

Warm two mugs with hot water. Pour whiskey and boiling water in one mug, ignite the liquid with fire and, while blazing, pour the liquid from one mug to the other four or five times to mix. If done well, this will have the appearance of a continuous stream of fire. Prepare a London dock glass (or Irish coffee glass) with syrup and lemon, and pour the flaming mixture into the glass.

Did drinks like this originate in Upstate New York? Perhaps not, but the man who made them famous certainly did.

A ROCHESTER BAR-KEEPER: PATSY MCDONOUGH

He was not nearly as famous or revered by modern cocktailians as Jerry Thomas. But Patsy McDonough was another Upstate New York bartender who contributed to the cocktail literature of the late nineteenth century. By the early 1880s, he had already worked at “leading bars” around the country for twenty-five years and was then serving as “head bar-keeper” at Lieder’s Hotel Brunswick in Rochester.

That background is included on the title page of McDonough’s Bar-Keeper’s Guide and Gentleman’s Sideboard Companion, which appears, from Library of Congress archives, to have been published about 1883.

In his introduction, McDonough writes, “The object of my book is to afford simple and practicable directions for manufacturing all kinds of plain and fancy drinks, that every man may become his own bar-keeper, at home or at the club-room, and at the same time giving to the professional bar-keeper my own extended experience behind the bar.”

The recipes, he says, “may be relied upon in every particular as accurate.… Tastes differ in certain cities, and certain drinks, prepared according to the prescriptions in this book, would not perhaps be acceptable all over the country.”

Aside from the recipes, McDonough offers a behind-the-scenes glimpse at the life of a bartender of the period:

The most unpleasant duties of a bar-keeper is the morning work. Then the bottles, reduced by the demands of the day and night previous, have to be refilled; the glasses used previous to closing, washed; the bar cleaned, and everything put in order for the day.…To keep a bar clean and neat during the day, the man in charge should have an abundance of towels—such as fall towels for the front of the bar, hand towels for the rear of the bar, fine linen towels for drying glasses and bottles, and a chamois towel for polishing the glassware.…The rear of the bar should be re-arranged at least once a week, and the weekly shifting of the glasses, decanters and bottles of different colors and shapes, will be a constant study for any bar-keeper who has a pride in his work.…So, too, the apparel of a first-class bar-keeper.…In the winter a neat, fur-trimmed cardigan jacket should be worn; and for summer months, a white duck coat with a white necktie should always be preferred. So, too, the tools necessary for work in a first-class bar, I would mention cork-screws, gimlet, shakers, ice picks, ice shaver, bar spoons, cocktail sieve, lemon knives, lemon squeezers, ice scoop, beer mallet, ale measures, faucets, wine cooler, &c.

For the drinks, his guide starts with this description: “The Cocktail is a very popular drink. It is most frequently called for in the morning and just before dinner; it is sometimes taken as an appetizer; it is a welcome companion on fishing excursions, and travelers often go provided with it on railroad journeys.”

McDonough lists many of the same drinks found in the contemporary editions by Jerry Thomas. It also features some whose names have Upstate New York references. Among them (with the recipes as given):

BUFFALO PUNCH. Fill large bar glass with shaved ice, one and one-half table-spoon of bar sugar, one wine-glass of Port Wine, one wine-glass of Brandy, three or four dashes of lime juice; shake well, and add fruit in season. Imbibe through a straw.

ROCHESTER PUNCH for a party of two. One pint imported Champagne, one wine-glass of Brandy, four slices of orange, two slices of pineapple, one table-spoon of powdered sugar to each glass; pour the Brandy on the fruit and sugar them, add the Champagne, which should be taken from the cooler; use a large bar glass; stir with a spoon.

ROCHESTER HOT. One lump of cut loaf sugar, one wine-glass of boiling water, one pony-wine-glass of Irish Whiskey, a small piece of toast, buttered. Use small bar glass

Another of the drinks found in McDonough’s guide is the Tom & Jerry.

TOM & JERRY: A JOYFUL UPSTATE NEW YORK

TRADITION

Walk into the Crystal Restaurant in downtown Watertown, New York, any time between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Eve, and you’re sure to see a large and boisterous crowd at the bar.

They’re gathered around a dark blue or black glass bowl and drinking from small milk-white cups with colorful lettering and images. Both the bowl and the glassware are marked with the words “Tom & Jerry.”

Yes, it’s Tom & Jerry season at the Crystal. This is no cat-and-mouse caper; it’s a lasting tribute to a warming winter drink from a bygone age.

The drink itself is a mixture of eggs, spices, rum and brandy that dates back to at least the early 1800s. It’s “a rich holiday elixir” in the words of New York Times writer Robert Simonson. It is, he continues in an essay in The Essential New York Times Book of Cocktails, “a relative of eggnog that flourished in America in the 19th and early 20th centuries.”

There was a time when restaurant bars and taverns across America served Tom & Jerrys in the traditional way that lingers at the Crystal, using a marked punch bowl and mugs. Then fans of the drink brought the tradition home, serving Tom & Jerrys at the holiday gatherings in their parlors.

“The milky broth was once so popular that an ancillary trade in Tom & Jerry punch-bowl sets sprang up,” Simonson writes. “You can still spot them in antiques stores, typically emblazoned with the drink’s name in Old English type.”

Simonson, who grew up in Wisconsin, goes on to observe that this old-fashioned libation “somehow clung to life in Wisconsin and bordering states, while falling into obscurity everywhere else.”

Watertown is the major city in Upstate New York’s “North Country,” a land where winter brings bitter cold temperatures, fierce winds off the Great Lakes and heavy snow, dubbed “lake effect.” In other words, it has a lot in common with northern Wisconsin.

It only takes a peek into the Crystal Restaurant during the holidays to see that Watertown is one of the places beyond Wisconsin where the Tom & Jerry clings to life.

“Even if we wanted to stop we couldn’t,” says Libby Dephtereos, who owns the Crystal with her husband, Peter. “Our customers won’t let us.”

In the book A Taste of Upstate New York, Libby Dephtereos gave this description of the scene at the Crystal during Tom & Jerry season to author Chuck D’Imperio:

This place gets packed every day from Thanksgiving to New Year’s. The bowl is on the bar and we make each Tom & Jerry to order. Sometimes the girls in the back are making thirty to forty at a time. The magic really does happen back there in the kitchen. Nobody sees the drink being made, and when it comes out to the bar everybody cheers. It is nonstop and it is a madhouse in here. A fun madhouse, though.

At the bar, the bartender warms your mug with hot water, scoops some batter in from the bowl and adds the liquor. The mix is a family secret, Dephtereos says. “There’s not really any measuring to it; everything is just thrown in.”

Everything about the Tom & Jerry service at the Crystal evokes old-school tradition. The bowl is an antique that Peter and Libby Dephtereos claimed from the historic former Hotel Woodruff, once located nearby. Most of the glassware dates to the mid-twentieth century. Libby Dephtereos says they find replacements on eBay or from customers. “People bring them in, saying they found these sets in their grandmother’s attic,” Libby Dephtereos said.

The restaurant itself, on Watertown’s historic downtown square, opened in 1925 and hasn’t changed much: pressed tin ceiling, wooden booths and floors and a menu of reasonably priced comfort food. Drinks are served from one of those old-time “stand up” bars. There are no seats or stools—never have been. Libby Dephtereos told D’Imperio that the original owner believed if you had so much to drink that you couldn’t stand, you should leave.

Peter Dephtereos’s family started working there in the 1920s and later bought the restaurant. Libby Dephtereos told D’Imperio that Peter’s grandfather, an immigrant from Greece, started the Crystal’s Tom & Jerry tradition.

But where, and when, did the Tom & Jerry really get its start? How did it acquire such a fanciful name? This is another of the murky tales that fill spirits and cocktails history. Simonson, in the New York Times, writes, “It is frequently (though not definitively) credited to Pierce Egan, the [early nineteenth-century] English chronicler of sports and popular culture. The name, it seems, refers to the lead characters in a book Egan wrote in 1821, Life in London or the Day and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorn, Esq., and His Elegant Friend, Corinthian Tom.

But there’s another story that often pops up (and is just as frequently debunked). It ties the creation of the Tom & Jerry and its name to the bartending celebrity Jerry Thomas, who just happened to be born in Sackets Harbor, not far from Watertown.

Here’s the account that appeared in the New York Times 1885 obituary of Thomas:

Jerry was of an inventive turn of mind and was constantly originating new combinations of drinks, some of which, like the “Tom & Jerry,” which he named after himself, became very popular, and, as they could not be patented, were quickly adopted by other saloons for the benefit of their patrons. The drink was first quaffed in 1847, and Mr. Thomas never wearied of telling the story of its first concoction. In repeating it to a friend a few months ago he said: “One day in California a gentleman asked me to give him an egg beaten up in sugar. I prepared the article and then I thought to myself, ‘How beautiful the egg and sugar would be with brandy in it!’ I ran to the gentleman and said ‘If you’ll only bear with me for five minutes I’ll fix you up a drink that’ll do your heartstrings good.’ He wasn’t at all averse to having his heartstrings improved so back I went and mixed the eggs and sugar, which I had beaten up into a kind of batter, with some brandy. Then I poured some hot water and stirred vigorously. The drink realized my expectations. It was the one thing I had been dreaming of for months. I named the drink after myself. I had two small white mice in those days, one of which I called Tom and the other Jerry. I combined the abbreviations in the drink, as Jeremiah P. Thomas would have sounded rather heavy, and that wouldn’t have done for a beverage.”

Tom & Jerry serving bowl and mugs at the Crystal Restaurant, Watertown. Author’s photo.

In Imbibe!, David Wondrich dismisses the claim. He cites references to the Tom & Jerry drink that appeared long before 1847, including one in a Salem, Massachusetts newspaper from 1827, two or three years before Thomas was born.

At the Crystal, Libby Dephtereos said she’d heard in recent years that a famous bartender named Jerry Thomas might have created the drink long ago, but she had no idea until she was interviewed for this book that he was from the Watertown area.

It seems coincidental, then, that the Tom & Jerry enjoys such a strong reputation so near his birthplace. For Dephtereos, it doesn’t matter. “It’s just such a great tradition,” she said. “We get so many people who come in during the holidays, some from far away, and greet their old friends over a Tom & Jerry or two.”

Whether he invented it or not, the Tom & Jerry appears in the first edition of Thomas’s cocktail book, How to Mix Drinks. Here’s his recipe, adapted and annotated for modern tastes by David Wondrich in Imbibe!

Tom & Jerry

From How to Mix Drinks by Jerry Thomas, Adapted by David Wondrich

Note: Thomas’s measurements appear first

(Wondrich’s adaptation in parentheses)

12 eggs

1½ teaspoons ground cinnamon

½ teaspoon ground cloves

½ teaspoon ground allspice

½ small glass (1 ounce) Jamaica rum

5 pounds (2 pounds) sugar

Use a punch bowl for the mixture: Beat the whites of the eggs to a stiff froth and the yolks until they are as thin as water; mix together and add the spice and rum. Thicken with sugar until the mixture attains the consistence of a light batter. (In his recipe, Thomas notes that “a teaspoonful of cream of tartar, or about as much carbonate of soda as you can get on a dime, will prevent the sugar from settling to the bottom of the mixture.”)

To deal out Tom & Jerry to customers: Take a small bar glass and to one tablespoonful of the above mixture, add one wineglass (2 ounces) of brandy and fill the glass with boiling water. Grate a little nutmeg on top. (Thomas notes that some bartenders of his era sometimes substituted a mixture of ½ brandy, ¼ Jamaica rum and ¼ Santa Cruz rum instead of just brandy. “This compound is usually mixed and kept in a bottle, and a wineglass (2 ounces) is used to each tumbler of Tom & Jerry,” Thomas notes.)

In Imbibe!, Wondrich notes that five pounds of sugar is a “crazy amount” by modern standards. He also notes that hot milk began to replace hot water by the early twentieth century. “It’s better that way, although there’s a certain austere ruggedness to the water version.” He suggests using three pounds of sugar if using water to add body to the finished drink. He also suggests rinsing the serving mugs with boiling water to warm them.