CHAPTER 1

La Belle France

I. SEA CHANGE

AT FIVE-FORTY-FIVE in the morning, Paul and I rousted ourselves from our warm bunk and peered out of the small porthole in our cabin aboard the SS America. Neither of us had slept very well that night, partially due to the weather and partially due to our rising excitement. We rubbed our eyes and squinted through the glass, and could see it was foggy out. But through the deep-blue dawn and swirling murk we spied rows of twinkling lights along the shore. It was Wednesday, November 3, 1948, and we had finally arrived at Le Havre, France.

I had never been to Europe before and didn’t know what to expect. We had been at sea for a week, although it seemed a lot longer, and I was more than ready to step onto terra firma. As soon as our family had seen us off in fall-colored New York, the America had sailed straight into the teeth of a North Atlantic gale. As the big ship heeled and bucked in waves as tall as buildings, there was a constant sound of bashing, clashing, clicking, shuddering, swaying, and groaning. Lifelines were strung along the corridors. Up . . . up . . . up . . . the enormous liner would rise, and at the peak she’d teeter for a moment, then down . . . down . . . down . . . she’d slide until her bow plunged into the trough with a great shuddering spray. Our muscles ached, our minds were weary, and smashed crockery was strewn about the floor. Most of the ship’s passengers, and some of her crew, were green around the gills. Paul and I were lucky to be good sailors, with cast-iron stomachs: one morning we counted as two of the five passengers who made it to breakfast.

I had spent only a little time at sea, on my way to and from Asia during the Second World War, and had never experienced a storm like this before. Paul, on the other hand, had seen every kind of weather imaginable. In the early 1920s, unable to afford college, he had sailed from the United States to Panama on an oil tanker, hitched a ride on a little ferry from Marseille to Africa, crossed the Mediterranean and Atlantic from Trieste to New York, crewed aboard a schooner that sailed from Nova Scotia to South America, and served briefly aboard a command ship in the China Sea during World War II. He’d experienced waterspouts, lightning storms, and plenty of the “primordial violence of nature,” as he put it. Paul was a sometimes macho, sometimes quiet, willful, bookish man. He suffered terrible vertigo, yet was the kind to push himself up to the top of a ship’s rigging in a fierce gale. It was typical that aboard the tossing SS America he did most of the worrying for the two of us.

Paul had been offered the job of running the exhibits office for the United States Information Service (USIS), at the American embassy in Paris. His assignment was to help promote French-American relations through the visual arts. It was a sort of cultural/propaganda job, and he was well suited for it. Paul had lived and worked in France in the 1920s, spoke the language beautifully, and adored French food and wine. Paris was his favorite city in the world. So, when the U.S. government offered him a job there, he jumped at the chance. I just tagged along as his extra baggage.

Travel, we agreed, was a litmus test: if we could make the best of the chaos and serendipity that we’d inevitably meet in transit, then we’d surely be able to sail through the rest of life together just fine. So far, we’d done pretty well.

We had met in Ceylon in the summer of 1944, when we’d both been posted there by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the CIA. Paul was an artist, and he’d been recruited to create war rooms where General Mountbatten could review the intelligence that our agents had sent in from the field. I was head of the Registry, where, among other things, I processed agents’ reports from the field and other top-secret papers. Late in the war, Paul and I were transferred to Kunming, China, where we worked for General Wedemeyer and continued our courtship over delicious Chinese food.

Although we had met abroad, we didn’t count our wartime in Asia as real living-time abroad: we were working seven days a week, sleeping in group quarters, and constantly at the beck and call of the military.

But now the war was over. We had been married in 1946, lived for two years in Washington, D.C., and were moving to Paris. We’d been so busy since our wedding day, September 1, 1946, that we’d never taken a proper honeymoon. Perhaps a few years in Paris would make up for that sorry state of affairs and give us a sort of working honeymoon. Well, it sounded like a good plan.

AS I GAZED through the porthole at the twinkling lights of Le Havre, I realized I had no idea what I was looking at. France was a misty abstraction for me, a land I had long imagined but had no real sense of. And while I couldn’t wait to step ashore, I had my reasons to be suspicious of it.

In Pasadena, California, where I was raised, France did not have a good reputation. My tall and taciturn father, “Big John” McWilliams, liked to say that all Europeans, especially the French, were “dark” and “dirty,” although he’d never actually been to Europe and didn’t know any Frenchmen. I had met some French people, but they were a couple of cranky spinster schoolteachers. Despite years of “learning” French, by rote, I could neither speak nor understand a word of the language. Furthermore, thanks to articles in Vogue and Hollywood spectaculars, I suspected that France was a nation of icky-picky people where the women were all dainty, exquisitely coiffed, nasty little creatures, the men all Adolphe Menjou–like dandies who twirled their mustaches, pinched girls, and schemed against American rubes.

I was a six-foot-two-inch, thirty-six-year-old, rather loud and unserious Californian. The sight of France in my porthole was like a giant question mark.

The America entered Le Havre Harbor slowly. We could see giant cranes, piles of brick, bombed-out empty spaces, and rusting half-sunk hulks left over from the war. As tugs pushed us toward the quay, I peered down from the rail at the crowd on the dock. My gaze stopped on a burly, gruff man with a weathered face and a battered, smoldering cigarette jutting from the corner of his mouth. His giant hands waved about in the air around his head as he shouted something to someone. He was a porter, and he was laughing and heaving luggage around like a happy bear, completely oblivious to me. His swollen belly and thick shoulders were encased in overalls of a distinctive deep blue, a very attractive color, and he had an earthy, amusing quality that began to ease my anxiety.

So THAT’S what a real Frenchman looks like, I said to myself. He’s hardly Adolphe Menjou. Thank goodness, there are actual blood-and-guts people in this country!

By 7:00 a.m., Paul and I were ashore and our bags had passed through customs. For the next two hours, we sat there smoking and yawning, with our collars turned up against the drizzle. Finally, a crane pulled our large sky-blue Buick station wagon—which we’d nicknamed “the Blue Flash”—out of the ship’s hold. The Buick swung overhead in a sling and then dropped down to the dock, where it landed with a bounce. It was immediately set upon by a gang of mécaniciens, men dressed in black berets, white butcher’s aprons, and big rubber boots. They filled the Flash with essence, oil, and water, affixed our diplomatic license plates, and stowed our fourteen pieces of luggage and half a dozen trunks and blankets away all wrong. Paul tipped them, and restowed the bags so that he could see out the back window. He was very particular about his car-packing, and very good at it, too, like a master jigsaw-puzzler.

As he finished stowing, the rain eased and streaks of blue emerged from the gray scud overhead. We wedged ourselves into the front seat and pointed our wide, rumbling nose southeast, toward Paris.

Paul’s photographs of the French countryside

II. SOLE MEUNIèRE

THE NORMAN COUNTRYSIDE struck me as quintessentially French, in an indefinable way. The real sights and sounds and smells of this place were so much more particular and interesting than a movie montage or a magazine spread about “France” could ever be. Each little town had a distinct character, though some of them, like Yvetot, were still scarred by gaping bomb holes and knots of barbed wire. We saw hardly any other cars, but there were hundreds of bicyclists, old men driving horses-and-buggies, ladies dressed in black, and little boys in wooden shoes. The telephone poles were of a different size and shape from those in America. The fields were intensely cultivated. There were no billboards. And the occasional pink-and-white stucco villa set at the end of a formal allée of trees was both silly and charming. Quite unexpectedly, something about the earthy-smoky smells, the curve of the landscape, and the bright greenness of the cabbage fields reminded us both of China.

Oh, la belle France—without knowing it, I was already falling in love!

AT TWELVE-THIRTY we Flashed into Rouen. We passed the city’s ancient and beautiful clock tower, and then its famous cathedral, still pockmarked from battle but magnificent with its stained-glass windows. We rolled to a stop in la Place du Vieux Marché, the square where Joan of Arc had met her fiery fate. There the Guide Michelin directed us to Restaurant La Couronne (“The Crown”), which had been built in 1345 in a medieval quarter-timbered house. Paul strode ahead, full of anticipation, but I hung back, concerned that I didn’t look chic enough, that I wouldn’t be able to communicate, and that the waiters would look down their long Gallic noses at us Yankee tourists.

It was warm inside, and the dining room was a comfortably old-fashioned brown-and-white space, neither humble nor luxurious. At the far end was an enormous fireplace with a rotary spit, on which something was cooking that sent out heavenly aromas. We were greeted by the maître d’hôtel, a slim middle-aged man with dark hair who carried himself with an air of gentle seriousness. Paul spoke to him, and the maître d’ smiled and said something back in a familiar way, as if they were old friends. Then he led us to a nice table not far from the fireplace. The other customers were all French, and I noticed that they were treated with exactly the same courtesy as we were. Nobody rolled their eyes at us or stuck their nose in the air. Actually, the staff seemed happy to see us.

As we sat down, I heard two businessmen in gray suits at the next table asking questions of their waiter, an older, dignified man who gesticulated with a menu and answered them at length.

“What are they talking about?” I whispered to Paul.

“The waiter is telling them about the chicken they ordered,” he whispered back. “How it was raised, how it will be cooked, what side dishes they can have with it, and which wines would go with it best.”

“Wine?” I said. “At lunch?” I had never drunk much wine other than some $1.19 California Burgundy, and certainly not in the middle of the day.

In France, Paul explained, good cooking was regarded as a combination of national sport and high art, and wine was always served with lunch and dinner. “The trick is moderation,” he said.

Suddenly the dining room filled with wonderfully intermixing aromas that I sort of recognized but couldn’t name. The first smell was something oniony—“shallots,” Paul identified it, “being sautéed in fresh butter.” (“What’s a shallot?” I asked, sheepishly. “You’ll see,” he said.) Then came a warm and winy fragrance from the kitchen, which was probably a delicious sauce being reduced on the stove. This was followed by a whiff of something astringent: the salad being tossed in a big ceramic bowl with lemon, wine vinegar, olive oil, and a few shakes of salt and pepper.

My stomach gurgled with hunger.

I couldn’t help noticing that the waiters carried themselves with a quiet joy, as if their entire mission in life was to make their customers feel comfortable and well tended. One of them glided up to my elbow. Glancing at the menu, Paul asked him questions in rapid-fire French. The waiter seemed to enjoy the back-and-forth with my husband. Oh, how I itched to be in on their conversation! Instead, I smiled and nodded uncomprehendingly, although I tried to absorb all that was going on around me.

We began our lunch with a half-dozen oysters on the half-shell. I was used to bland oysters from Washington and Massachusetts, which I had never cared much for. But this platter of portugaises had a sensational briny flavor and a smooth texture that was entirely new and surprising. The oysters were served with rounds of pain de seigle, a pale rye bread, with a spread of unsalted butter. Paul explained that, as with wine, the French have “crus” of butter, special regions that produce individually flavored butters. Beurre de Charentes is a full-bodied butter, usually recommended for pastry dough or general cooking; beurre d’Isigny is a fine, light table butter. It was that delicious Isigny that we spread on our rounds of rye.

Rouen is famous for its duck dishes, but after consulting the waiter Paul had decided to order sole meunière. It arrived whole: a large, flat Dover sole that was perfectly browned in a sputtering butter sauce with a sprinkling of chopped parsley on top. The waiter carefully placed the platter in front of us, stepped back, and said: “Bon appétit!”

I closed my eyes and inhaled the rising perfume. Then I lifted a forkful of fish to my mouth, took a bite, and chewed slowly. The flesh of the sole was delicate, with a light but distinct taste of the ocean that blended marvelously with the browned butter. I chewed slowly and swallowed. It was a morsel of perfection.

In Pasadena, we used to have broiled mackerel for Friday dinners, codfish balls with egg sauce, “boiled” (poached) salmon on the Fourth of July, and the occasional pan-fried trout when camping in the Sierras. But at La Couronne I experienced fish, and a dining experience, of a higher order than any I’d ever had before.

Along with our meal, we happily downed a whole bottle of Pouilly-Fumé, a wonderfully crisp white wine from the Loire Valley. Another revelation!

Then came salade verte laced with a lightly acidic vinaigrette. And I tasted my first real baguette—a crisp brown crust giving way to a slightly chewy, rather loosely textured pale-yellow interior, with a faint reminder of wheat and yeast in the odor and taste. Yum!

We followed our meal with a leisurely dessert of fromage blanc, and ended with a strong, dark café filtre. The waiter placed before us a cup topped with a metal canister, which contained coffee grounds and boiling water. With some urging by us impatient drinkers, the water eventually filtered down into the cup below. It was fun, and it provided a distinctive dark brew.

Paul paid the bill and chatted with the maître d’, telling him how much he looked forward to going back to Paris for the first time in eighteen years. The maître d’ smiled as he scribbled something on the back of a card. “Tiens,” he said, handing it to me. The Dorin family, who owned La Couronne, also owned a restaurant in Paris, called La Truite, he explained, while Paul translated. On the card he had scribbled a note of introduction for us.

“Mairci, monsoor,” I said, with a flash of courage and an accent that sounded bad even to my own ear. The waiter nodded as if it were nothing, and moved off to greet some new customers.

Paul and I floated out the door into the brilliant sunshine and cool air. Our first lunch together in France had been absolute perfection. It was the most exciting meal of my life.

BACK IN THE FLASH, we continued to Paris along a highway built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. With double roadways on each side of a grass median, and well-engineered overpasses and underpasses, it reminded us of the Hutchinson River Parkway, outside of New York City. That impression faded as dusk came on and the unmistakable silhouette of the Eiffel Tower loomed into sight, outlined with blinking red lights.

Paris!

At nightfall, we entered the city via the Porte de Saint-Cloud. Navigating through the city was strange and hazardous. The streetlights had been dimmed, and for some reason (wartime habit?) Parisians drove with only their parking lights on. It was nearly impossible to see pedestrians or road signs, and the thick traffic moved slowly. Unlike in China or India, where people also drove by parking light, the Parisians would constantly flash on their real headlights for just a moment when they thought there was something in the road.

Across the Pont Royal, up the Rue du Bac, nearly to Boulevard Saint-Germain, and then we pulled over at 7 Rue Montalembert in front of the Hôtel Pont Royal. We were exhausted, but thrilled.

Paul unloaded the Flash and drove off into the misty dark in search of a garage that was reputedly five minutes away. We’d been told that it wasn’t safe to leave the car on the street at night. The Buick wagon was considerably bulkier than the local Citroëns and Peugeots, and Paul was anxious to find a safe berth for what the garagistes called our “autobus américain.” I accompanied our bags up to our room, but noticed that the hotel seemed to be swaying from side to side, like the America: I had yet to regain my land legs.

An hour later, and still no sign of Paul. I was hungry and growing concerned. Finally, he reappeared in a lather, saying: “I had a hell of a time. I went up instead of down the Boulevard Raspail, then came back via Saint-Germain thinking it was Raspail, then got stuck on a one-way street. So I parked the car and walked. Eventually I found the garage, but then I couldn’t find the car—I thought I’d left it on Raspail, but it was on Saint-Germain! Nobody knew where the garage was, or the hotel. Finally, I brought car to garage and me to you at the hotel. . . . Let’s eat!”

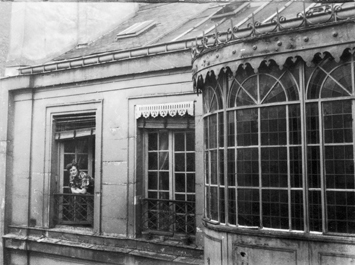

Me looking out at Paris from the Hôtel Pont Royal

We went to a little place on Saint-Germain where the food was fine, although nothing compared with La Couronne (the standard by which I would now measure every eatery), and disappointingly packed with tourists. I had only been in Paris for a few hours but already considered myself a native.

Paul’s job at the USIS was to “inform the French people by graphic means about the aspects of American life that the [United States] government deems important.” The idea was to build goodwill between our nations, to reinforce the idea that America was a strong and reliable ally, that the Marshall Plan was designed to help France get back on its feet (without telling Paris how to run its affairs), and to insinuate that rapacious Russia was not to be trusted. It seemed straightforward.

On his first day of work, Paul discovered that the USIS exhibits office had been leaderless for months and was a shambles. He was to oversee a staff of eight, all French—five photographers, two artists, and one secretary—who were demoralized, overworked, underpaid, riven with petty jealousies, and hobbled by a lack of basic supplies. There was little or no photographic film, paper, developer, or flashbulbs. Even essentials like scissors, bottles of ink, stools—or a budget—were missing. The lights in his office would conk out three or four times a day. Because there were no proper files, or shelves, most of his unit’s fifty thousand photographic prints and negatives were stuffed into ragged manila envelopes or old packing boxes on the floor.

In the meantime, the ECA, the Economic Cooperation Administration, which administered the Marshall Plan, was sending orders in big, thoughtless clumps: Prepare hundreds of exhibit materials for a trade fair in Lyon! Introduce yourself to all the local politicians and journalists! Send posters to Marseille, Bordeaux, and Strasbourg! Be charming at the ambassador’s champagne reception for three hundred VIPs! Put on an art show for an American ladies’ club! Et cetera. Paul had endured far worse during the war, but he fumed that such working conditions were “ridiculous, naïve, stupid, and incredible!”

I wandered the city, got lost, found myself again. I engaged the garage man in a lengthy, if not completely comprehensible, discussion about retarding the Flash’s spark to reduce the “ping.” I went into a big department store and bought a pair of slippers. I went into a boutique and bought a chic green-feathered hat. I got along “assez bien.”

At the American embassy I collected our ration books, pay information, commissary tickets, travel vouchers, leave sheets, cartes d’identité, and business cards. Mrs. Ambassador Caffrey had let it be known that she felt protocol had slipped around the embassy, and insisted that people like us—on the bottom of the diplomatic totem pole—leave our cards with everyone of equivalent or superior rank: that meant I had to leave over two hundred cards for Paul and over one hundred for me. Phooey!

ON NOVEMBER 5, a banner headline in the International Herald Tribune proclaimed that Harry S. Truman had been elected president, defeating Thomas Dewey at the eleventh hour. Paul and I, devoted Democrats, were exultant. My father, “Big John” McWilliams, a staunchly conservative Republican, was horrified.

Pop was a wonderful man on many counts, but our different world-views were a source of tension that made family visits uncomfortable for me and miserable for Paul. My mother, Caro, who had died from the effects of high blood pressure, and now my stepmother, Philadelphia McWilliams, known as Phila, were apolitical but went along with whatever Pop said for the sake of domestic harmony. My brother, John, the middle sibling, was a mild Republican; my younger sister, Dorothy, stood to the left of me. My father was pained by his daughters’ liberal leanings. He had assumed I would marry a Republican banker and settle in Pasadena to live a conventional life. But if I’d done that I’d probably have turned into an alcoholic, as a number of my friends had. Instead, I had married Paul Child, a painter, photographer, poet, and mid-level diplomat who had taken me to live in dirty, dreaded France. I couldn’t have been happier!

Reading about Truman’s election victory, I imagined the doom and gloom around Pasadena: it must have seemed like the End of Life as Big John knew it. Eh bien, tant pis, as we Parisians liked to say.

PARIS SMELLED OF SMOKE, as though it were burning up. When you sneezed, you blew sludge onto your handkerchief. This was partly due to some of the murkiest fog on record. It was so thick, the newspapers reported, that airplanes were grounded and transatlantic steamers were stuck in port for days. Everyone you met had a “fog drama” to tell. Some people were so terrified of getting lost that they spent all night in their cars, others missed plunging into the Seine by a centimeter, and several people drove for hours in the wrong direction, only to find themselves at a metro stop on the outskirts of town; they abandoned their cars and took the train home, but, upon emerging from the metro, got lost on foot. The fog insinuated itself everywhere, even inside the house. It was disconcerting to see clouds in your rooms, and it gave you a vague sense of being suffocated.

But on our first Saturday in Paris, we awoke to a brilliant bright-blue sky. It was thrilling, as if a curtain had been pulled back to reveal a mound of jewels. Paul couldn’t wait to show me around his city.

We began at the Deux Magots café, where we ordered café complet. Paul was amused to see that nothing had changed since his last visit, back in 1928. The seats inside were still covered with orange plush, the brass light fixtures were still unpolished, and the waiters—and probably the dust balls in the corners—were the same. We sat outside, on wicker seats, munching our croissants and watching the morning sun illuminate the chimney pots. Suddenly the café was invaded by a mob of camera operators, soundmen, prop boys, and actors, including Burgess (Buzz) Meredith and Franchot Tone, costumed and grease-painted as shabby “Left Bank artists.” Paul, who had once worked as a busboy/scenery-painter in Hollywood, chatted with Meredith about his movie, and how people in the film business were always the same agreeable type, whether in Paris, London, or Los Angeles.

We wandered up the street. Paul—mid-sized, bald, with a mustache and glasses, dressed in a trench coat and beret and thick-soled shoes—strode ahead, eyes alert and noticing everything, his trusty Graflex camera strapped around his shoulder. I followed, eyes wide open, mouth mostly shut, heart skipping with excitement.

At Place Saint-Sulpice, black-outfitted wedding guests were kissing each other on both cheeks by the fountain, and the building where Paul’s mother had lived twenty years earlier was unchanged. Glancing up at a balcony, he spied a flower box she had made, now filled with marigolds. But at the corner, a favorite old building had disappeared. Not far away, the house where Paul’s twin, Charlie, and his wife, Fredericka, known as Freddie, had once lived was now just a rubble-strewn lot (had it been blown to bits by a bomb?). Next to the theater on Place de l’Odéon we noticed a small marble plaque that read: “In memory of Jean Bares, killed at this spot in defense of his country, June 10, 1944.” There were many of these somber reminders around the city.

We wended our way across the Seine and through the green Tuileries and along dank backstreets that smelled of rotting food, burned wood, sewage, old plaster, and human sweat. Then up to Montmartre and Sacré-Coeur, and The View over the whole city. Then down again, back over the Seine and, via Rue Bonaparte, to lunch at a wonderful old restaurant called Michaud.

Parisian restaurants were very different from American eateries. It was such fun to go into a little bistro and find cats on the chairs, poodles under the tables or poking out of women’s bags, and chirping birds in the corner. I loved the crustacean stands in front of cafés, and began to order boldly. Moules marinières was a new dish to me; the mussels’ beards had been removed, and the flesh tasted lovely in a way I had never expected it to. There were other surprises, too, such as the great big juicy pears grown right there in Paris, so succulent you could eat them with a spoon. And the grapes! In America, grapes bored me, but the Parisian grapes were exquisite, with a delicate, fugitive, sweet, ambrosial, and irresistible flavor.

As we explored the city, we made a point of trying every kind of cuisine, from fancy to hole-in-the-wall. In general, the more expensive the establishment, the less glad they were to see us, perhaps because they could sense us counting our centimes. The red-covered Guide Michelin became our Bible, and we decided that we preferred the restaurants rated with two crossed forks, which stood for medium quality and expense. A meal for two at such an establishment would run us about five dollars, which included a bottle of vin ordinaire.

Michaud became our favorite place for a time. Paul had learned about it through friends at the embassy, and it was just around the corner from Rue du Bac, where Rue de l’Université turns into Rue Jacob. It was a relaxed, intimate two-forker. The proprietress, known simply as Madame, stood about four feet three inches tall, had a neat little French figure, red hair, and a thrifty Gallic “save everything” quality. A waiter would take your order and bring it to Madame’s headquarters at the bar. In one motion, she’d glance at the ticket, dive into a little icebox, and emerge with the carefully apportioned makings of your meal—meat, fish, or eggs—put it on a plate, and send it into the kitchen to be cooked. She poured the wine in the carafes. She made change at the register. If sugar ran low, she’d trot upstairs to her apartment to fetch it in a brown cardboard box; then she’d measure just the right amount into a jar, with not a single grain wasted.

Despite her frugality, Madame had an intimate and subtle charm. In a typical evening, you’d always shake her hand three times: upon entering, when she dropped by your table in the midst of your meal, and at the door as you left. She was happy to sit down with a cup of coffee to talk, but only for a moment. She’d join in a celebration with a glass of champagne, but for just long enough. The waiters at Michaud were all around sixty years old and carried themselves with the same intimate yet reserved manner she did. The clientele seemed to be made up of Parisians from the quartier and a smattering of foreigners who’d stumbled over this little prize and had kept it to themselves.

That afternoon, Paul ordered rognons sautés au beurre (braised kidneys) with watercress and fried potatoes. I was tempted by many things, but finally succumbed once again to sole meunière. I just couldn’t get over how good it was, the sole crisp and bristling from the fire. With a carafe of vin compris and a perfectly soft slice of Brie, the entire lunch came to 970 francs, or about $3.15.

Computing l’addition all depended on which exchange rate you used. We U.S. Embassy types were only allowed to exchange dollars for francs at the official rate, about 313 francs to the dollar. But on the black market the exchange was 450 francs to the dollar, an improvement of more than 33 percent. Though we could have used the extra money, it was illegal, and we didn’t dare risk our pride, or our posting, to save a few sous.

After more wandering, we had a very ordinary dinner, but finished the evening on a high note with dessert at Brasserie Lipp. I was feeling buoyant, and so was Paul. We discussed the stereotype of the Rude Frenchman: Paul declared that, in Paris of the 1920s, 80 percent of the people were difficult and 20 percent were charming; now the reverse was true, he said—80 percent of Parisians were charming and only 20 percent were rude. This, he figured, was probably an aftereffect of the war. But it might also have been due to his new outlook on life. “I am less sour now than I used to be,” he admitted. “It’s because of you, Julie.” We analyzed one another, and concluded that marriage and advancing age agreed with us. Most of all, Paris was making us giddy.

Paul’s scenes of Paris

“Lipstick on my belly button and music in the air—thaat’s Paris, son,” Paul wrote his twin, Charlie. “What a lovely city! What grenouilles à la provençale. What Châteauneuf-du-Pape, what white poodles and white chimneys, what charming waiters, and poules de luxe, and maîtres d’hôtel, what gardens and bridges and streets! How fascinating the crowds before one’s café table, how quaint and charming and hidden the little courtyards with their wells and statues. Those garlic-filled belches! Those silk-stockinged legs! Those mascara’d eyelashes! Those electric switches and toilet chains that never work! Hola`! Dites donc! Bouillabaisse! Au revoir!”

III. ROO DE LOO

“IT’S EASY TO GET the feeling that you know the language just because when you order a beer they don’t bring you oysters,” Paul said. But after seeing a movie about a clown who cried through his laughter, or laughed through his tears—we couldn’t tell which—even Paul felt discombobulated. “So much for my vaunted language skills,” he griped.

At least he could communicate. The longer I was in Paris, the worse my French seemed to get. I had gotten over my initial astonishment that anyone could understand what I said at all. But I loathed my gauche accent, my impoverished phraseology, my inability to communicate in any but the most rudimentary way. My French “u”s were only worse than my “o”s.

This was brought home at Thanksgiving, when we went to a cocktail party at Paul and Hadley Mowrer’s apartment. He wrote a column for the New York Post and did broadcasts for the Voice of America. She was a former Mrs. Ernest Hemingway, whom Paul had first met in Paris in the 1920s. Hadley was extremely warm, not very intellectual, and the mother of Jack Hemingway, who had been in the OSS during the war and was called Bumby. At the Mowrers’ Thanksgiving party, more than half the guests were French, but I could barely say anything interesting at all to them. I am a talker, and my inability to communicate was hugely frustrating. When we got back to the hotel that night, I declared: “I’ve had it! I’m going to learn to speak this language, come hell or high water!”

A few days later, I signed up for a class at Berlitz: two hours of private lessons three times a week, plus homework. Paul, who was a lover of word games, made up sentences to help my pronunciation: for the rolling French “r”s and extended “u”s, he had me repeat the phrase “Le serrurier sur la Rue de Rivoli” (“The locksmith on the Rue de Rivoli”) over and over.

IN THE MEANTIME, I had discovered an apartment for rent that was large, centrally located, and a bit weird. It was two floors of an old four-story hôtel particulier, at 81 Rue de l’Université. A classic Parisian building, it had a gray cement façade, a grand front door about eight feet high, a small interior courtyard, and an open-topped cage elevator. It was situated in the Seventh Arrondissement, on the Left Bank, an ideal location, one block in from the Seine, between the Assemblée Nationale and the Ministry of Defense. Paul’s office at the U.S. Embassy was just across the river. Day and night, the bells of the nearby Church of Sainte-Clothilde tolled the time; it was a sweet sound, and I loved hearing it.

On December 4, we moved out of the Hôtel Pont Royal and into 81 Rue de l’Université. On the first floor lived our landlady, the distinguished Madame Perrier. She was seventy-eight, thin, with gray hair and a lively French face; she dressed in black and wore a black choker around her neck. With her lived her daughter, Madame du Couédic; son-in-law, Hervé du Couédic; and two grandchildren. On the ground floor, a concierge, whom I thought of as an unhappy crone, occupied a little apartment.

Madame Perrier was a cultured woman, an amateur bookbinder and photographer. The widow of a World War I general, she had also lost a son and a daughter within three months of each other. Yet she glistened like an old hand-polished copper fire-hood. It gave me great pleasure to see someone as fully mature and mellow but also as lively and aglow as she was. Madame Perrier became the model for how I wanted to look in my dotage. Her daughter, Madame du Couédic, looked like a typical French gentry-woman, with a spare frame, dark hair, and a somewhat formal manner. Her husband was also pleasant, but had an air of cool formality; he ran a successful paint business. By unspoken consent, we all got to know each other slowly, and eventually considered each other dear friends.

Paul and I were given the second and third floors. The elevator opened into a large, dark salon on the second floor. Madame Perrier’s taste dated to the last century, and the salon looked faintly ridiculous: decorated in Louis XVI style, it was high-ceilinged, with gray walls, four layers of gilded molding, inset panels, an ugly tapestry, thick curtains around one window, fake electric sconces, broken electric switches, and weak light. Sometimes I’d blow a fuse in there simply by plugging in the electric iron, which made me curse. But the salon’s proportions were fine, and we improved things by editing out most of the chairs and tables.

We turned an adjacent room into our bedroom. The walls in there were covered in green cloth and so many plates, plaques, carvings, and whatnots that it looked like the inside of a freshly sliced plum cake. We removed most of the wall hangings, as well as a clutter of chairs, tables, cozy-corners, and hassocks, and stored them in an empty room upstairs that we named the oubliette (forgettery). Sensitive to the feelings of Madame Perrier, and in typically organized fashion, Paul drew up a diagram showing where each artifact had hung, so when it came time for us to leave we could re-create her decor exactly.

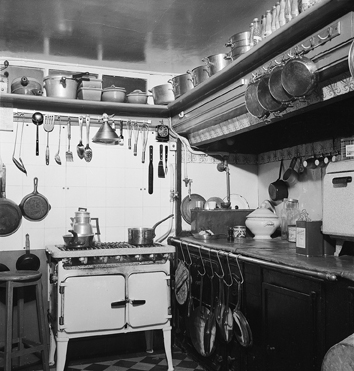

The kitchen was on the third floor, and was connected to the salon by a dumbwaiter that worked only some of the time. The kitchen was large and airy, with an expanse of windows along one side, and an immense stove—it seemed ten feet long—which took five tons of coal every six months. On top of this monster stood a little two-burner gas contraption with a one-foot-square oven, which was barely usable to heat plates or make toast. Then there was a four-foot-square shallow soapstone sink with no hot water. (We discovered we couldn’t use it in the winter, because the pipes ran along the outside of the building and froze up.)

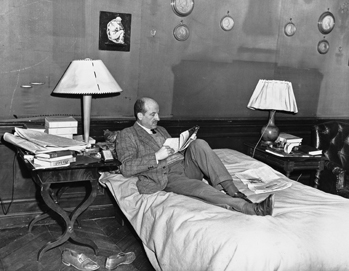

The building had no central heating and was as cold and damp as Lazarus’s tomb. Our breath came out in great puffs indoors. So, like true Parisians, we installed an ugly little potbellied stove in the salon and sealed ourselves off for the winter. We stoked that bloody stove all day, and it provided a faint trace of heat and a strong stench of coal gas. Huddled there, we made quite a pair: Paul, dressed in his Chinese winter jacket, would sit midway between the potbellied stove and the forty-five-watt lamp, reading. I, charmingly outfitted in a thick padded coat, several layers of long underwear, and some dreadfully huge red leather shoes, would sit at a gilt table attempting to type letters with stiff fingers. Oh, the glamour of Paris!

I didn’t mind living in primitive conditions with Charlie and Freddie Child at their hand-built cabin in the Maine woods, but I saw no sense in being even more primitive while living in the “cultural center of the world.” So I set up a makeshift hot-water system (i.e., a tub of water set over a gas geyser), a dishwashing station, and covered garbage cans. Then I hung a nice row of cooking implements on the kitchen wall, including my Daisy can-opener and a Magnagrip, which made me feel at home.

Saying “81 Rue de l’Université” proved too much of a mouthful, and we quickly dubbed our new home “Roo de Loo,” or simply “81.”

Rue de Loo came with a femme de ménage (maid) named Frieda. She was about twenty-two, a farm girl who had been kicked around by life; she had a darling, illegitimate nine-year-old daughter whom she boarded in the country. Frieda lived on the fourth floor at Roo de Loo, in appallingly primitive conditions. She had no bathroom or hot water, so I set aside a corner of our bathroom on the third floor for her to use.

I was not used to having domestic help, and the arrangement with Frieda took some adjustment for the both of us. She made a decent soup but was not a skilled cook, and she had the annoying habit of dumping the silverware on the table in a great crashing pile. One evening, I sat her down before dinner for a little consultation. In my inadequate French, I tried to explain how to arrange a table, how to serve from the left, how she should take time and care to do things right. No sooner had I commenced my well-intentioned instruction than she broke into sniffles, snorts, and sobs and rushed upstairs murmuring tragic French phrases. I followed her up there and tried again. Using my Berlitz-enhanced subjunctive, I explained how I wanted her to enjoy life, to work well but not too hard, and so on. This brought more sobs, tears, and blank stares. Eventually, after a few fits and starts, we got the hang of each other.

It was French law that an employer pay for an employee’s Social Security, which worked out to about six to nine dollars every three months; we also paid for Frieda’s health insurance. It was a fair system, and we were happy to help her. But I held on to my very mixed feelings about living with domestic help. Part of the problem was that I found I rather enjoyed shopping and homekeeping.

Feeling nesty, I went to Le Bazar de l’Hôtel de Ville, known as “le B.H.V.,” an enormous market filled with aisle upon aisle of cheaply made merchandise. It took me two hours just to walk around and get my bearings. Then I bought pails, dishpans, brooms, soap rack, funnel, light plugs, wire, bulbs, and garbage cans. I filled the back of the Flash with my loot, drove it to 81, then returned to le B.H.V. for more. I even bought a new kitchen stove for ninety dollars. On another jaunt, I loaded up with a frying pan, three big casserole dishes, and a potted flower.

Paris was still recovering from the war, and coffee rations ran out quickly, cosmetics were expensive, and decent olive oil was as precious as a gem. We didn’t have an icebox, and like most Parisians just stuck our milk bottles out the window to keep cool. Luckily, we had brought plates, silver, linen, blankets, and ashtrays with us from the States, and we were able to shop for American goods at the embassy PX.

I made up a budget, but immediately grew depressed. Paul’s salary was $95 a week. After I’d divided our fixed costs into separate envelopes—$4 for cigarettes, $9 for auto repairs and gas, $10 for insurance, magazines, and charities, and so forth—we’d have about $15 left for clothes, trips, and amusements. It wasn’t much. We were trying to live like civilized people on a government salary, which simply wasn’t possible. Fortunately, I had a small amount of family money that produced a modest income, although we were determined to save it.

PAUL’S FIRST USIS EXHIBIT—a series of photographs, maps, and text explaining the Berlin Airlift—was hung in the window of the TWA office on the Champs-Élysées. It proved very popular with passersby. In the meantime, he was feeling his way slowly through the embassy bureaucracy, taking care not to step on people’s toes or Achilles’ heels.

His French staff was increased to ten, and by all accounts they loved “M’sieur Scheeld.” But his American colleagues were not quite sure what to make of my husband. Paul was a very accomplished exhibits man, took great pride in a job well done, and knew the importance of establishing reliable channels of communication (“the channels, the channels,” he’d mutter). But he wasn’t professionally ambitious. For those who cared about vaulting up the career ladder, having lunch or socializing with the right people was terribly important; Paul often had a sandwich alone with his camera on the banks of the Seine. Or he’d come home for leftovers with me—chicken soup, sausages, herring, and warm bread—followed by a brief nap. This habit was probably not good for his career, but that wasn’t the point. We were enjoying life together in Paris.

Paul was ambitious for his painting and photography, which he did on evenings or weekends, but even those ambitions were more aesthetic than commercial. He was a physical person, a black belt in judo, a man who loved to tie complicated knots or carve a piece of wood. Naturally, he would have loved recognition as an Important Artist. But his motivation for making paintings and photographs wasn’t fame or riches: his pleasure in the act of creating, “the thing itself,” was reward enough.

Understaffed, running out of film, and facing a raft of promises unkept by the State Department, Paul was forced to cancel an early-winter vacation in order to cover for others at the embassy. In the meantime, I had volunteered to create a cataloguing system for the USIS’s fifty thousand orphaned photographs. I had done similar file-work during the war, but this was a real struggle. Not only was cross-referencing all of the prints close to impossible, I was trying to design an idiot-proof system for other people—French people—to use. In the hope of finding a standard approach to cataloguing, I visited five big photo libraries, only to discover that no standard existed. Photo cataloguing in France was generally left to ladies who’d been doing the job for thirty years and could recognize every print by its smell or something.

OUR DOMESTIC CIRCLE was completed when we were adopted by a poussiequette we named Minette (Pussy). We assumed she was a mutt, perhaps a reformed alley cat—a sly, gay, mud-and-cream-colored little thing. I had never been much of an animal person, although we’d had small dogs in Pasadena. But Paul and Charlie liked cats and were devoted to the briard, a wonderfully woolly, slobbery French sheepdog they referred to as “the Noblest Breed of All.” (We’d had one in Washington—Maquis—who had died tragically young by choking on a sock.)

“Mini” soon became an important part of our lives. She liked to sit in Paul’s lap during meals, and paw tidbits off his plate when she thought he wasn’t looking. She spent a great deal of time playing with a brussels sprout tied to a string, or peering under our radiators with her tail switching. Once in a while, she’d proudly present us with a mouse. She was my first cat ever, and I thought she was marvelous. Soon I began to notice cats everywhere, lurking in alleys or sunning themselves on walls or peering down at you from windows. They were such interesting, independent-minded creatures. I began to equate them with Paris.

IV. ALI-BAB

PAUL AND I were intent on meeting French people, but that was not as easy as one might think. For one thing, Paris was crawling with Americans, most of them young, and they liked to cling together in great expat flocks. We knew quite a few of these Yanks, and liked them well enough, but as time went on, I found that they grew less and less interesting to me—and I, no doubt, to them. There were two ladies from Los Angeles, for instance, whom I once considered “just wonderful,” and who lived not far from us on the Left Bank, but who completely faded from my life within a few months. This wasn’t an intentional separation from my past—it was just the natural evolution of things.

Upon departing the States we’d been given many letters of introduction to friends-of-friends we “must meet.” But we were so busy, and so excited, that it took a long time to get to the list. Plus we didn’t have a telephone.

You forget how much you rely on something as simple as a phone until you don’t have one. After we’d moved into 81, we had placed an order for a phone, and waited. First a man came by to see if we lived where we said we did. Then two men visited to make a “study” of our situation. Then another man appeared to find out if we really wanted a phone. The process was very French, and made me laugh, especially when I thought of how quickly such a transaction would have taken place in the States. In the meantime, I was making phone calls at the post office, the PTT (“Postes, Télégraphes et Téléphones”), where there were only two pay phones, and one could only buy one jeton, or token, at a time. It took hours to make a three-minute call, but I enjoyed it because I was able to practice my French on the two ladies at the counter. They were curious about how things were done in America, and filled me in on all the local gossip about who had done what during the war, how la grippe (the flu) was spreading like wildfire, and where to find the best prices in the quartier.

When we finally did get to calling on our friends-of-friends, one of the first couples we met was Hélène and Jurgis Baltrusaitis. He was a taciturn, inward-looking Lithuanian art historian who had just returned from a sabbatical year at Yale and New York University. Hélène was an outgoing enthusiast, the stepdaughter of Henri Foçillon, a famed art historian who had been Jurgis’s mentor. They had a fourteen-year-old boy named Jean, who distressed his parents by madly chewing American bubble gum. We hit it off immediately, especially with dear Hélène, who was a “swallow-life-in-big-gulps” kind of person. Whereas Jurgis saw Sunday as an opportunity to burrow deeply into his books, Hélène couldn’t wait to join Paul and me for a jaunt through the countryside.

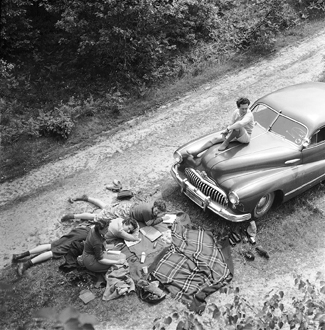

One December Sunday, the three of us drove out to the Fontainebleau forest. The cloudy gray sky broke open and turned blue, the air was vigorously cool, and the sun shone brightly. After an hour or so of hiking, we broke out a picnic basket brimming with sausages, hard-boiled eggs, baguettes, pâtisseries, and a bottle of Moselle wine. We ate lying against twisted gray rocks covered with emerald-green moss. Except for the yawping crows in the beech trees, we were the only ones in that enchanted place. On the way home, we stopped in the little town of Étampes. At a café next to a twelfth-century church, a mob of locals, all red in the face from wine, were celebrating something with expansive singing in hoarse, quavering voices. It was a lovely scene.

The longer I was in France, the stronger and more ecstatic my feelings for it became. I missed my family, of course, and things like certain cosmetics or really good coffee. But the U.S. seemed like an increasingly distant and dreamlike place.

The Baltrusaitises—the Baltrus—introduced us to le groupe Foçillon: fifteen or twenty art historians, many of whom had been disciples of Hélène’s stepfather. They met once a week chez Baltru for wine, a nibble of something, and impassioned debate over, say, whether or not a certain false transept in a certain church was built before or after 1133. Regulars at these meetings included Louis Grodecki, a violently opinionated Pole, and Verdier, a smooth and witty Frenchman, who were constantly attacking and counterattacking each other over medieval arcana; Jean Asche, a husky former Resistance hero who’d been captured and sent to Buchenwald by the Nazis, and whose wife, Thérèse, became a dear friend of mine; and Bony, a university lecturer. It was a sociable, intellectually vigorous, and very French circle—exactly the sort of friends Paul and I had been hoping to find, but would never have discovered on our own.

Among all of these accomplished art historians, Paul was the only practicing artist. He had learned stained-glass making in the 1920s, when he’d worked on the windows at the American Church in Paris. Although he suffered terrible vertigo, he had forced himself to climb high into the eaves to work on some of the trickiest windows, thereby earning the nickname Tarzan of the Apse. To show his appreciation for le groupe Foçillon, Paul designed a stained-glass medallion, about ten inches round, showing each of the group’s members in a symbolic pose. It was a characteristic gesture, one that helped us gain quick acceptance into this unusual group.

SURROUNDED BY GORGEOUS FOOD, wonderful restaurants, and a kitchen at home—and an appreciative audience in my husband—I began to cook more and more. In the late afternoon, I would wander along the quay from the Chambre des Députés to Notre Dame, poking my nose into shops and asking the merchants about everything. I’d bring home oysters and bottles of Montlouis–Perle de la Touraine, and would then repair to my third-floor cuisine, where I’d whistle over the stove and try my hand at ambitious recipes, such as veal with turnips in a special sauce.

But I had so much more to learn, not only about cooking, but about shopping and eating and all the many new (to me) foods. I hungered for more information.

It came, at first, from Hélène, my local guide and language coach. She was a rather knowing instructor, and soon I began to use her French slang and to see Paris as she saw it. Although she wasn’t very interested in cooking, Hélène loved to eat and knew a lot about restaurants. One day she loaned me a great big old-fashioned cookbook by the famed chef Ali-Bab. It was a real book: the size of an unabridged dictionary, printed on thick paper, it must have weighed eight pounds. It was written in old French, and was out of print, but was full of the most succulent recipes I’d ever seen. And it was also very amusingly written, with little asides about cooking in foreign lands and an appendix on why gourmets are fat. Even on sunny days, I’d retreat to my bed and read Ali-Bab—“with the passionate devotion of a fourteen-year-old boy to True Detective stories,” Paul noted, accurately.

I had worked on my French diligently, and was able to read better and say a little more every day. At first my communications in the marketplace had consisted of little more than finger-pointing and simplistic grunts: “Bon! Ça! Bon!” Now when I went to L’Olivier, the olive-oilery on the Rue de Rivoli—a small shop filled with crocks of olives and bottles of olive oil—I could actually carry on a lengthy conversation with the jolly olive man.

My tastes were growing bolder, too. Take snails, for instance. I had never thought of eating a snail before, but, my, tender escargots bobbing in garlicky butter were one of my happiest discoveries! And truffles, which came in a can, and were so deliciously musky and redolent of the earth, quickly became an obsession.

I shopped at our neighborhood marketplace on la Rue de Bourgogne, just around the corner from 81. My favorite person there was the vegetable woman, who was known as Marie des Quatre Saisons because her cart was always filled with the freshest produce of each season. Marie was a darling old creature, round and vigorous, with a crease-lined face and expressive, twinkling eyes. She knew everyone and everything, and she quickly sized me up as a willing disciple. I bought mushrooms or turnips or zucchini from her several times a week; she taught me all about shallots, and how to tell a good potato from a bad one. She took great pleasure in instructing me about which vegetables were best to eat, and when; and how to prepare them correctly. In the meantime, she’d fill me in on so-and-so’s wartime experience, or where to get a watchband fixed, or what the weather would be tomorrow. These informal conversations helped my French immeasurably, and also gave me the sense that I was part of a community.

We had an excellent crémerie, located on the place that led into the Rue de Bourgogne. It was a small and narrow store, with room for just five or six customers to stand in, single-file. It was so popular that the line would often extend out into the street. Madame la Proprietress was robust, with rosy cheeks and thick blond hair piled high, and she presided from behind the counter with cheerful efficiency. On the wide wooden shelf behind her stood a great mound of freshly churned, sweet, pale-yellow butter waiting for pieces to be carved as ordered. Next to the mound sat a big container of fresh milk, ready to be ladled out. On the side counters stood the cheese—boxes of Camembert, large hunks of Cantal, and wheels of Brie in various stages of ripeness—some brand-new and almost hard, others soft to the point of oozing.

The drill was to wait patiently in line until it was your turn, and then give your order clearly and succinctly. Madame was a whiz at judging the ripeness of cheese. If you asked for a Camembert, she would cock an eyebrow and ask at what time you wished to serve it: would you be eating it for lunch today, or at dinner tonight, or would you be enjoying it a few days hence? Once you had answered, she’d open several boxes, press each cheese intently with her thumbs, take a big sniff, and—voilà!—she’d hand you just the right one. I marveled at her ability to calibrate a cheese’s readiness down to the hour, and would even order cheese when I didn’t need it just to watch her in action. I never knew her to be wrong.

The neighborhood shopped there, and I got to know all the regulars. One of them was a properly dressed maid who shopped in the company of her household’s proud, prancing black poodle. I saw her on a regular basis, and she was always dressed in formless gray or brown clothes. But one day I noticed that she had arrived without the poodle and dressed in a new, trim black costume. I could see the eyes of everyone in line shifting to observe her. As soon as Madame spotted the new finery, she summoned the maid to the front of the line and served her with great politesse. When she swept by me and out the door with a slight Mona Lisa smile on her lips, I asked my neighbor in line why the maid had been given such deferential treatment.

“She has a new job,” the woman explained, with a knowing look. “She works for la comtesse. Did you see how she’s dressed today? Now she’s practically a comtesse herself!”

I laughed, and as I approached Madame to give my order, I thought: “So much for the French Revolution.”

IN MID-DECEMBER, a little snow flurry sugared the cobblestones, and Paul and I were struck by the almost total lack of holiday commercialism in the streets. Occasionally you’d see a man dragging a fir tree across the Place de la Concorde, a sprig of holly over a doorway, or kids lined up in front of a department store watching the animated figures. But in comparison with the crass Christmas ballyhoo in Washington or Los Angeles, Paris was wonderfully calm and picturesque.

We shared Christmas Day with the Mowrers. They were a good deal older and wiser than me, and I thought of them as semi-parental figures. Their big news was that Bumby Hemingway was engaged to marry a tall Idaho girl named Byra “Puck” Whitlock.

PARIS WAS WONDERFULLY WALKABLE. There wasn’t much car traffic, and one could easily hike from the Place de la Concorde to the top of Montmartre in a half-hour. We carried a pocket-sized map-book with a brown cover called Paris par Arrondissement, and would intentionally wander off the beaten path. Paul, the mad photographer, always carried his trusty camera slung over his shoulder and had a small sketchpad stuffed in his pocket. I discovered that when one follows the artist’s eye one sees unexpected treasures in so many seemingly ordinary scenes. Paul loved to photograph architectural details, café scenes, hanging laundry, market women, and artists along the Seine. My job was to use my height and long reach to block the sun over his camera lens as he carefully composed a shot and clicked the shutter.

In our wanderings we had discovered La Truite, the restaurant owned by the cousins of the Dorins who ran La Couronne in Rouen. La Truite was a cozy place off le Faubourg Saint-Honoré, behind the American embassy. The chef was Marcel Dorin, a distinguished old-schooler, assisted by his son. They did a splendid roast chicken: suspended on a string, the bird twirled in front of a glowing electric grill; every few minutes, a waiter would give it a spin and baste it with the juices that dripped down into a pan filled with roasting potatoes and mushrooms. Oh, those were such fine, fat, full-flavored birds from Bresse—one taste, and I realized that I had long ago forgotten what real chicken tasted like! But La Truite’s true glory was its sole à la normande, a poem of poached and flavored sole fillets surrounded by oysters and mussels, and napped with a wonder-sauce of wine, cream, and butter, and topped with fluted mushrooms. “Voluptuous” was the word. I had never imagined that fish could be taken so seriously, or taste so heavenly.

One cold afternoon just before New Year’s, Paul and I strolled up to the Buttes-Chaumont park. At the top of the hill, by the little Greek temple, we looked back at Sacré-Coeur on Montmartre, now silhouetted through layers of mist by the declining sun. In a little bistro, we warmed ourselves with coffee and stared at the city through dirty windows. Behind Paul’s head, a fat white cat slept on a pile of ledgers. Beside me, a large dog made up of many breeds gave a big “Woof!,” then settled into a deep snooze. Two little monkeys gobbled peanuts and wrestled furiously over a folding chair, filling the air with clatter and squeals. Three boys played dice at a nearby table. An old man wrote a letter. At the bar, a frowsy blonde gossiped with a horn-rimmed man in a beret. A fat white dog dressed in a green turtleneck waddled by, and the blonde cooed: “Ah, qu’il est joli, le p’tit chou.”

V. PROVENCE

“I FEEL IT IS my deep-seated duty to show you the rest of France,” Paul said one day. And so, at the end of February 1949, he, Hélène, and I drove out of cold, gray Paris down to bright, warm Cannes.

The tone for our trip was set by lunch in Pouilly, four hours out of Paris. Paul had written ahead to Monsieur Pierrat, a well-regarded chef, asking him to fix us “a fine meal.” He did. It took us over three hours to work our way through Pierrat’s terrines, pâtés, saucissons, smoked ham, fish in sauce américaine, coq-sang, salade verte, fromages, crêpes flambées—all accompanied by a lovely Pouilly-Fumé 1942. We finished with (and were finished off by) a rich and creamy dessert called prune, for which the cheerful chef joined us. It was an extraordinary meal. And by its conclusion we were utterly flooded with a soft, warm, glowing pleasure.

We spent the night in Vienne, and were still so full of Chef Pierrat’s lunch that we could only fit a small dinner into our gullets. Our bodies hummed with contentment. Even the Flash seemed to purr.

“Incroyable! Ravissant!” we intoned in unison the next day, as vista after gorgeous vista revealed itself. Every field was an explosion of fragrant and colorful bougainvilleas, brooms, mimosas, or daisies. Warm, salty breezes blew off the Mediterranean. There were dramatic rocky cliffs along the coast, snow-topped Alps looming in the background. The air was cool and the sky was brilliant. It was all so beautiful and fragrant that I found my senses were nearly overwhelmed.

Hélène was as gay as a bobolink and an amusing source of art-historical nuggets. Paul—with one large camera, one small camera, and a monocular hung around his body—looked like a veritable American Tourist, as he happily snapped photos left and right. If it wasn’t a beautiful castle on a hilltop, then it was bands of sun-filtered mist settling in the peach orchards below. If it wasn’t a perfect fourteenth-century stone bridge, then it was a deep valley with a rushing brook bright as quicksilver. We ate nougat de Montélimar. We inhaled the smell of sage. We sang “Sur le Pont d’Avignon” as we Flashed under the bridge at Avignon. We sat on a hillside outside of Aix drinking Pouilly. At Miramar, we gathered armfuls of mimosas with the Mowrers, whom we’d met with there. In the evening, we watched the lights of Cannes winking across the darkening water.

This was my first experience of the famous Côte d’Azur, an area that was already close to Paul’s heart. It appealed to me deeply, in part because it was reminiscent of southern California, and in part because of its own rugged vitality.

On the return loop to Paris, we crossed over the mountains, and the scenery changed dramatically. Grasse, a hothouse filled with flowers, gave way to great barren limestone ridges, like hardened taffy, and tumbling rivers that were a bright aqua-blue color from the glacial melt. Nestled into hillsides were little towns where every building was made of local stone that had weathered for hundreds of years. After coffee and apéritifs at Castellane, in a deep mountain valley, we climbed up and up into sparkling cold air, the sun beating warm. Crossing Alpine passes, we drove into a world of evergreens and snow, with towns clustered in the mountain cracks like periwinkles. At Grenoble we drove into a dramatic cloud of icy fog, and spent the night in a snug little hotel in Les Abrets.

As we crossed Burgundy the next morning, the Mowrers grew tired of our dawdling and accelerated back to Paris. We were happy to take our time. We passed valley towns whose names sounded like a carillon: Montrachet, Pommard, Vougeot, Volnay, Meursault, Nuits-Saint-Georges, Beaune. The nuns, the wine, the lovely courtyards—there were so many extraordinary things to see, and by the end of the day our cups had filled to the brim. By eight-thirty that night we were back at the Roo de Loo, where we unloaded armloads of mimosas.

SPRING HAD SPRUNG in Paris. In the park on the Île de la Cité, the grass was bright green and alive with new babies, doting grannies, and fussing nannies. Along the river, barges were tied up side-by-side, and their rigging was decorated with drying white sheets and socks. Women sunned and sewed pink underwear. Fishermen dangled their feet in the water and snacked on moules. Minette had spring fever. She bolted out the window onto the roof and made gurgling noises, raced up and down the stairs, leapt into my lap then out again, then sat in the middle of the rug gurgling some more. The vet had informed me that she was not a mutt at all, but a rare type of Spanish cat called le tricolaire, which pleased me no end. When she started to gobble up our handpicked mimosa, we called her Minette Mimosa McWilliams Child.

In early April, my younger sister, Dorothy, arrived. She stood six foot three to my six-two, and was known in the family as Dort, from our childhood nicknames. She was Dort-the-Wort, or Wortesia, and I was called Julia Pulia, or, in less charitable moments, Juke-the-Puke. (Our brother, John, somehow escaped a nickname.) Dort had just graduated from Bennington, was single, and didn’t have any idea of what she wanted to do in life. So I encouraged her to come stay with us in Paris, rent-free. That was an offer that would warm the heart of any red-blooded American girl, and she hopped on the next boat.

Not in the least intimidated by her lack of French, Dort made a big impression on her first day at 81, when, for fun, she picked up the phone and began to call stores: “Bong-joor!” she honked. “Quelle heure êtes-vous fermé? . . . Mair-ci!”

Dort was five years younger than me, and fifteen years younger than Paul. She and I weren’t all that close, and, to be honest, when she arrived I felt as if I knew Hélène Baltru better than my own flesh and blood. But the longer Dort stayed with us, the closer we became.

Parisians took a shine to “the tall American girl,” and my outgoing sister’s willingness to do whatever it took to communicate. The results of her efforts were occasionally hilarious. There was, for instance, the day she went to the hairdresser’s for a shampoo and a trim and sweetly asked: “Monsieur, voulez-vous couper mes chevaux avant ou après le champignon?” The hairdresser looked at her quizzically while the ladies under the hairdryers broke into laughter. What Dort had been trying so earnestly to ask was: “Sir, would you like to cut my hair before or after the shampoo?” But it came out as: “Sir, would you like to cut my horses before or after the mushroom?”

She bought a nifty little Citroën for eleven hundred dollars. It was black, had four seats and a minuscule engine. She loved it, except that on her second day of ownership it got a short circuit at 6:00 p.m., in the middle of the rush hour in the middle of la Place de la Concorde, and tied up traffic in the center of the city. When she finally made it back home that night, poor Dort burst into tears of rage. We calmed her, and assured her that everything would be all right. Our garagistes gave the car a once-over, and soon Dorothy was zipping around town, looking for work, and staying out late with the youthful expat crowd.

ON JUNE 25, Bumby Hemingway married Puck Whitlock.

Bumby was twenty-five, short, with a square, muscular body, stiff blond hair, and a clean-cut, outdoorsy look. During the war he had parachuted behind enemy lines for the OSS to form teams of agents, and although the Germans captured him a number of times, he’d always managed to escape. Now he was in Berlin, working for U.S. Army intelligence. The wedding was held in Paris because he didn’t have enough leave-time to fly home. Besides, his mother and stepfather lived there. And it was Paris.

Puck was tall, dark, and slim, a strong and attractive Idaho girl, who had once worked for United Airlines. She had been married to Lieutenant Colonel Whitlock, a pilot killed in action over Germany. She and Bumby had met in Sun Valley, Idaho, in 1946, and he had been pursuing her ever since. They hardly knew a soul in Paris, so I acted as her matron of honor, and Paul and Dort escorted people to their seats.

The wedding was held in the American Church, on Rue de Berri, where Paul had made his reputation as Tarzan of the Apse. The officiant was Joseph Wilson Cochran, an American who had married Charlie and Freddie in that very space, in April 1926. It was a perfectly natural and unpompous ceremony, just like the Mowrers themselves. There was quite a crowd at the reception, including the writer Alice B. Toklas—an odd little bird in a muslin dress and a big floppy hat—and Sylvia Beach, owner of the famed Shakespeare & Co. bookstore. (Papa Hemingway did not attend.) The weather was heavenly: clear blue sky with high, wispy clouds, the landscape bright green and yellow, with roses abloom in the Tuileries. By the end of the afternoon, I was thoroughly marinated with strawberries and cherries, champagne, brandy, Monbazillac, Montrachet, and Calvados, and speckled by tidbits of grass.

VI. LE GRAND VÉFOUR

WHEN FRIEDA, our emotional femme de ménage, took a job as a concierge in another building, Marie des Quatre Saisons helped us find a replacement. The new girl, Coquette, chased our dust chickens and brightened our giltwork part-time, from eight to eleven every morning. But her real job was with a prince and princess who lived around the corner.

Coquette was very sweet but a little nutty, and in private we referred to her as “Coo-Coo” Coquette. Like Frieda, she was of humble origins, and, not surprisingly, was rather bowled over by the glamorous prince and princess. La princesse was no ordinary princess, Coo-Coo breathlessly informed me, but a “double princess,” and she was English! The prince, Philippe de B—— (a name pronounced “boy,” appropriately), had a château and was the son of a noted scientist. They had four Pekingese dogs, who were so special and so cute, Coo-Coo said, that they were practically human. “Oh, madame!” she’d sigh, the prince and princess were so noble, so chic, so much a part of the fabulous “tout Paris” café set. But the dogs were never walked and made pee-pee all over the apartment. As a result, the apartment smelled like a poubelle (garbage bin). And how did the princess react? Well, she would grab anything she could lay her hands on—one of the prince’s shirts, a table napkin, a nightgown, or even one of her own silk dresses—to wipe up the mess.

In August, the princess and her dogs left for vacation in Normandy, leaving the prince alone in Paris. This was not a good thing, for he was “un peu difficile.” Coo-Coo would prepare him a delicious lunch, but the prince wouldn’t appear until 3:00 p.m., after drinking apéritifs at a café all morning with his loutish friends. He complained about the cost of potatoes. He refused to pay the four hundred francs he owed the old woman who sewed up his coat. And when he finally decamped to the château, he neglected to pay Coo-Coo’s Social Security and the two thousand francs he owed her in salary. She was mortified. But he was a prince. What could she do?

Well, it didn’t take long for the neighborhood to get wind of Coo-Coo’s dilemma. And then the horrible truth was revealed: the prince and princess owed money all up and down the Rue de Bourgogne. Alors, everyone from the vegetable-cart lady to the tripier hated them and threw up their hands in horror when their names were mentioned!

When the prince and princess returned from their vacances, the situation did not improve. The prince would scrounge up a bit of money, then spend it all on horse races or apéritifs. The princess would “buy” a dress from a leading fashion house, wear it to a big affair, and return it for a refund. It was a scandale!

Finally, Coo-Coo had had enough, and rebelled. She suggested to the prince that if he didn’t have the money to buy potatoes, or to pay her, he should sell his title, or perhaps the château, to make ends meet. He ignored her. And when the princess treated her with extra insensitivity, Coo-Coo announced she was going to quit. But she didn’t. After all, it meant quite a lot to “les gens” that she worked for a prince and princess, even if they were cheapskate layabouts. And they owed her quite a lot of back pay, which she was hoping to recoup at least part of. I found it all deeply fascinating.

ONE DAY, Paul and I were exploring the Palais Royal park when we peeked in the windows of a beautiful old-style restaurant tucked into a corner under the arched colonnade at the far end. The dining room was resplendent with gilded decorations, a painted ceiling, cut glass and mirrors, ornate rugs and fine fabrics. It was called Le Grand Véfour. We had unknowingly stumbled onto one of the most famous of the old Parisian restaurants, which had been in business since about 1750. The maître d’hôtel noticed our interest, and waved us in. It was near lunchtime, and though we were hardly used to such elegance, we looked at each other and said, “Why not?”

There weren’t many patrons yet, and we were seated in a gorgeous semicircular banquette. The headwaiter laid menus before us, and then the sommelier, an imposing but kindly Bordeaux specialist in his fifties, arrived. He introduced himself with a nod: “Monsieur Hénocq.” The restaurant began to fill up, and over the course of the next two hours we had a leisurely and nearly perfect luncheon. The meal began with little shells filled with sea scallops and mushrooms robed in a classically beautiful winy cream sauce. Then we had a wonderful duck dish, and cheeses, and a rich dessert, followed by coffee. As we left in a glow of happiness, we shook hands all around and promised almost tearfully to return.

What remained most vividly with me as we strolled away was the graciousness of our reception and the deep pleasure I’d experienced from sitting in those beautiful surroundings. Here we were, two young people obviously of rather modest circumstances, and we had been treated with the utmost cordiality, as if we were honored guests. The service was deft and understated, and the food was spectacular. It was expensive, but, as Paul said, “you are so hypnotized by everything there that you feel grateful as you pay the bill.”

Me looking out the window of the Roo de Loo

We went back to the Véfour every month or so after that, especially once we’d learned how to get invited there by wealthy and in-the-know friends. Because I was tall and outgoing and Paul was so knowledgeable about wine and food, Monsieur Hénocq and the Véfour’s wait staff always gave us the royal treatment. And that is where we first laid eyes on Grande Dame Colette. The famous novelist lived in an apartment in the Palais Royal, and the Véfour kept a special seat reserved in her name in a banquette at the end of the dining room. She was a short woman with a striking, almost fierce visage, and a wild tangle of gray hair. As she paraded regally through the dining room, she avoided our eyes but observed what was on everyone’s plate and twitched her mouth.

VII. LA MORTE-SAISON

THE NEWSPAPERS CLAIMED that the summer of 1949 was the worst sécheresse, or drought, since 1909. Riverbeds were filled with stones, fields were toasted gold, and the grass was crunchy to walk on. Leaves were drying up on trees, crops of vegetables were destroyed, grapes withered on the vine. With almost no water for hydroelectric power, people began to worry about the price of food in the coming winter. Air-conditioning was nonexistent.

On weekends, everyone headed out of town to cool off in a favorite hidden picnic spot. Many couples used tandem bicycles. The men would sit in front and women in back, usually dressed in matching costumes of, say, blue shorts, red shirt, and white hat. They’d furiously pedal along the highways, sometimes with a baby in a box on the handlebars, or a little dog in a box jiggling on the back fender.

On the Fourth of July, a reception for several thousand was held at the U.S. Embassy, and it seemed that every American in Paris was there, all talking at once. We were surprised to run into five people who we didn’t know were living in the city, including our old friends Alice and Dick, who were acting very strange. I felt that Alice, in particular, was snubbing us. I didn’t understand why. Perhaps she was miserable. But then she suddenly blurted out how much she loathed the Parisians, whom she considered horrid, mean, grasping, chiseling, and unfriendly in every way. She couldn’t wait to leave France, she claimed, and would never return.

Alice’s words were still ringing in my ears the next morning, when I went marketing and suffered a flat tire, broke a milk bottle, and forgot to bring a basket for my strawberries. Yet every person I met was helpful and sweet, and my nice old fish lady even gave me a free fish-head for Minette.

I was flummoxed and upset by Alice. She was someone I had once considered a good and sympathetic friend, but I just didn’t understand her anymore. In contrast to her, I felt a lift of pure happiness every time I looked out the window. I had come to the conclusion that I must really be French, only no one had ever informed me of this fact. I loved the people, the food, the lay of the land, the civilized atmosphere, and the generous pace of life.

AUGUST IN PARIS was known as la morte-saison, “the dead season,” because everybody who could possibly vacate did so as quickly as possible. A great emptying out of the city took place, as hordes migrated toward the mountains and coasts, with attendant traffic jams and accidents. Our favorite restaurants, the creamery, the meat man, the flower lady, the newspaper lady, and the cleaners all disappeared for three weeks. One afternoon I went into Nicolas, the wine shop, to buy some wine and discovered that everyone but the deliveryman had left town. He was minding the store, and in the meantime was studying voice in the hope of landing a role at the opera. Sitting next to him was an old concierge who, twenty-five years earlier, had been a seamstress for one of the great couturiers on la Place Vendôme. She and the deliveryman reminisced about the golden days of Racine and Molière and the Opéra Comique. I was delighted to stumble in on these two. It seemed that in Paris you could discuss classic literature or architecture or great music with everyone from the garbage collector to the mayor.

On August 15, I turned thirty-seven years old. Paul bought me the Larousse Gastronomique, a wonder-book of 1,087 pages of sheer cookery and foodery, with thousands of drawings, sixteen color plates, all sorts of definitions, recipes, information, stories, and gastronomical know-how. I devoured its pages even faster and more furiously than I had Ali-Bab.

By now I knew that French food was it for me. I couldn’t get over how absolutely delicious it was. Yet my friends, both French and American, considered me some kind of a nut: cooking was far from being a middle-class hobby, and they did not understand how I could possibly enjoy doing all the shopping and cooking and serving by myself. Well, I did! And Paul encouraged me to ignore them and pursue my passion.