CHAPTER 2

Le Cordon Bleu

I. CHEF BUGNARD

AT 9:00 A.M. on Tuesday, October 4, 1949, I arrived at the École du Cordon Bleu feeling weak in the knees and snozzling from a cold. It was then that I discovered that I’d signed up for a yearlong Année Scolaire instead of a six-week intensive course. The Année cost $450, which was a serious commitment. But after much discussion, Paul and I agreed that the course was essential to my well-being and that I’d plunge ahead with it.

My first cooking class was held in a sunny kitchen on the building’s top floor. My classmates were an English girl and a French girl of about my age, neither of whom had done any cooking at all. (To my great surprise, I’d discovered that many Frenchwomen didn’t know how to cook any better than I did; quite a lot of them had no interest in the subject whatsoever, though most were expert at eating in restaurants.) This “housewife” course was so elementary that after two days I knew it wasn’t what I’d had in mind at all.

I sat down with Madame Élizabeth Brassart, the school’s short, thin, rather disagreeable owner (she had taken over from Marthe Distel, who had run the school for fifty years), and explained that I’d had a more rigorous program in mind. We discussed my level of cooking knowledge, and her classes on haute cuisine (high-end, professional cooking) and moyenne cuisine (middle-brow cooking). She made it quite clear that she didn’t like me, or any Americans: “They can’t cook!” she said, as if I weren’t sitting right in front of her. In any event, Madame Brassart decreed that I was not advanced enough for haute cuisine—a six-week course for experts—but that I’d be suitable for the yearlong “professional restaurateurs” course that had conveniently just begun. This class was taught by Chef Max Bugnard, a practicing professional with years of experience.

“Oui!” I said without a moment’s hesitation.

At this point I began to really miss my sister-in-law, Freddie Child. We had grown so close in Washington, D.C., that when people said, “Here come the twins,” they meant me and Freddie, not Paul and Charlie. She was an excellent, intuitive cook, and, to scare our husbands, we’d joke about opening a restaurant called “Mrs. Child & Mrs. Child, of the Cordon Bleu.”

Learning to cut a chicken with Chef Bugnard

Secretly, I was somewhat serious about this idea, and was trying to convince her to join me at the Cordon Bleu. But she couldn’t tear herself away from her husband and three children in Pennsylvania. Eh bien, so I would be on my own.

It turned out that the restaurateurs’ class was made up of eleven former GIs who were studying cooking under the auspices of the GI Bill of Rights. I never knew if Madame Brassart had placed me with them as a form of hazing or merely because she was trying to squeeze out a few more dollars, but when I walked into the classroom the GIs made me feel as if I had invaded their boys’ club. Luckily, I had spent most of the war in male-dominated environments and wasn’t fazed by them in the least.

The eleven GIs were very “GI” indeed, like genre-movie types: nice, earnest, tough, basic men. Most of them had worked as army cooks during the war, or at hot-dog stands in the States, or they had fathers who were bakers and butchers. They seemed serious about learning to cook, but in a trade-school way. They were full of entrepreneurial ideas about setting up golf driving-ranges with restaurants attached, or roadhouses, or some kind of private trade in a nice spot back home. After a few days in the kitchen together, we became a jolly crew, though in my cold-eyed view there wasn’t an artist in the bunch.

In contrast to the housewife’s sun-splashed classroom upstairs, the restaurateurs’ class met in the Cordon Bleu’s basement. The kitchen was medium-sized, and equipped with two long cutting tables, three stoves with four burners each, six small electric ovens at one end, and an icebox at the other end. With twelve pupils and a teacher, it was hot and crowded down there.

The saving grace was our professor, Chef Bugnard. What a gem! Medium-small and plump, with thick round-framed glasses and a waruslike mustache, Bugnard was in his late seventies. He had been dans le métier most of his life: starting as a boy at his family’s restaurant in the countryside, he had done stages at various good restaurants in Paris, worked in the galleys of transatlantic steamers, and refined his technique under the great Escoffier in London for three years. Before the Second World War, he owned a restaurant, Le Petit Vatel, in Brussels. The war cost him Le Petit Vatel, but he had been recruited to the Cordon Bleu by Madame Brassart, and obviously loved his role as éminence grise there. And who wouldn’t? The job allowed him to keep regular hours and spend his days teaching students who relished his every word and gesture.

Because there was so much new information to take in every day, it was confusing at first. All twelve of us cut vegetables, stirred the pots, and asked questions at once. Most of the GIs struggled to follow Bugnard’s rat-a-tat delivery, which made me glad that I had developed my language skills before launching into cooking. Even so, I had to keep my ears open and make sure to ask questions, even if they were dumb questions, when I didn’t understand something. I was never the only one confused.

Bugnard set out to teach us the fundamentals. We began making sauce bases—soubise, fond brun, demi-glace, and madère. Later, to demonstrate a number of techniques in one session, Bugnard would cook a full meal, from appetizer to dessert. So we’d learn about, say, the proper preparation of crudités, a fricassee of veal, glazed onions, salade verte, and several types of crêpes Suzettes. Everything we cooked was eaten for lunch at the school, or sold.

Despite being overstretched, Bugnard was infinitely kind, a natural if understated showman, and he was tireless in his explanations. He drilled us in his careful standards of doing everything the “right way.” He broke down the steps of a recipe and made them simple. And he did so with a quiet authority, insisting that we thoroughly analyze texture and flavor: “But how does it taste, Madame Scheeld?”

One morning he asked, “Who will make oeufs brouillés today?”

The GIs were silent, so I volunteered for scrambled-egg duty. Bugnard watched intently as I whipped some eggs and cream into a froth, got the frying pan very hot, and slipped in a pat of butter, which hissed and browned in the pan.

“Non!” he said in horror, before I could pour the egg mixture into the pan. “That is absolutely wrong!”

The GIs’ eyes went wide.

With a smile, Chef Bugnard cracked two eggs and added a dash of salt and pepper. “Like this,” he said, gently blending the yolks and whites together with a fork. “Not too much.”

He smeared the bottom and sides of a frying pan with butter, then gently poured the eggs in. Keeping the heat low, he stared intently at the pan. Nothing happened. After a long three minutes, the eggs began to thicken into a custard. Stirring rapidly with the fork, sliding the pan on and off the burner, Bugnard gently pulled the egg curds together—“Keep them a little bit loose; this is very important,” he instructed. “Now the cream or butter,” he said, looking at me with raised eyebrows. “This will stop the cooking, you see?” I nodded, and he turned the scrambled eggs out onto a plate, sprinkled a bit of parsley around, and said, “Voilà!”

His eggs were always perfect, and although he must have made this dish several thousand times, he always took great pride and pleasure in this performance. Bugnard insisted that one pay attention, learn the correct technique, and that one enjoy one’s cooking—“Yes, Madame Scheeld, fun!” he’d say. “Joy!”

It was a remarkable lesson. No dish, not even the humble scrambled egg, was too much trouble for him. “You never forget a beautiful thing that you have made,” he said. “Even after you eat it, it stays with you—always.”

I was delighted by Bugnard’s enthusiasm and thoughtfulness. And I began to internalize it. As the only woman in the basement, I was careful to keep up an appearance of sweet good humor around “the boys,” but inside I was cool and intensely focused on absorbing as much information as possible.

As the weeks of cooking classes wore on, I developed a rigid schedule.

Every morning, I’d pop awake at 6:30, splash water across my puffy face, dress quickly in the near dark, and drain a can of tomato juice. By 6:50 I was out the door as Paul was beginning to stir. I’d walk seven blocks to the garage, jump into the Blue Flash, and roar up the street to Faubourg Saint-Honoré. There I’d find a parking spot and buy one French and one U.S. newspaper. I’d find a warm café, and would sip café-au-lait and chew on hot fresh croissants while scanning the papers with one eye and monitoring the street life with the other.

At 7:20 I’d walk two blocks to school and don my “uniform,” an ill-fitting white housedress and a blue chef’s apron with a clean dish towel tucked into the waist cord. Then I’d select a razor-sharp paring knife and start to peel onions while chitchatting with the GIs.

At 7:30 Chef Bugnard would arrive, and we’d all cook in a great rush until 9:30. Then we’d talk and clean up. School let out at about 9:45, and I would do a quick shop and zip home. There I’d get right back to cooking, trying my hand at relatively simple dishes like cheese tarts, coquilles Saint-Jacques, and the like. At 12:30 Paul would come home for lunch, and we’d eat and catch up. He’d sometimes take a quick catnap, but more often would rush back across the Seine to put out the latest brushfire at the embassy.

At 2:30 the Cordon Bleu’s demonstration classes began. Typically, a visiting chef, aided by two apprentices, would cook and explain three or four dishes—demonstrating how to make, say, a soufflé au fromage, decorate a galantine de volaille, prepare épinards à la crème, and end with a finale of charlotte aux pommes. The demonstration chefs were businesslike and did not waste a lot of time “warming up” the class. They’d start right in at 2:30, giving the ingredients and proportions, and talking us through each step as they went. We’d finish promptly at 5:00.

The demonstrations were held in a big square room with banked seats facing a demonstration kitchen up on a well-lit stage. It was like a teaching hospital, where medical interns sat watching in an amphitheater while the famous surgeon—or, in our case, chef—demonstrated how to amputate a leg—or make a cream sauce—onstage. It was an effective way of delivering a lot of information quickly, and the chefs demonstrated technique and took questions as they went. The afternoon sessions were open to anyone willing to pay three hundred francs. So, aside from the regular Cordon Bleu students, the audience was filled with housewives, young cooks, old men, strays off the street, and the odd gourmet or two.

We learned all sorts of dishes—perdreaux en chartreuse (roasted partridges placed in a mold decorated with savory cabbage, beans, and julienned carrots and turnips); boeuf bourguignon; little fish en lorgnette (a pretty dish in which the fish’s backbone is cut out, the body is rolled up to the head, and then the whole is deep-fried in boiling fat); chocolate ice cream (made with egg yolks); and cake icing (made with sugar boiled to a viscous consistency, beaten into egg yolks, then beaten with softened butter and flavorings to make a wonderfully thick icing).

All of the demonstration teachers were good, but two stood out.

Pierre Mangelatte, the chef at Restaurant des Artistes, on la Rue Lepic, gave wonderfully stylish and intense classes on cuisine traditionnelle: quiches, sole meunière, pâté en croûte, trout in aspic, ratatouille, boeuf en daube, and so on. His recipes were explicit and easy to understand. I scribbled down copious notes, and found them easy to follow when I tried the recipes later at home.

The other star was Claude Thilmont, the former pastry chef at the Café de Paris, who had trained under Madame Saint-Ange, the author of that seminal work for the French home cook, La Bonne Cuisine de Madame E. Saint-Ange. With great authority, and a pastry chef’s characteristic attention to detail, Thilmont demonstrated how to make puff pastry, pie dough, brioches, and croissants. But his true forte was special desserts—wonderful fruit tarts, layer cakes, or showstoppers like a charlotte Malakoff.

I was in pure, flavorful heaven at the Cordon Bleu. Because I had already established a good basic knowledge of cookery on my own, the classes acted as a catalyst for new ideas, and almost immediately my cooking improved. Before I’d started there, I would often put too many herbs and spices into my dishes. But now I was learning the French tradition of extracting the full, essential flavors from food—to make, say, a roasted chicken taste really chickeny.

It was a breakthrough when I learned to glaze carrots and onions at the same time as roasting a pigeon, and how to use the concentrated vegetable juices to fortify the pigeon flavor, and vice versa. And I was so inspired by the afternoon demonstration on boeuf bourguignon that I went right home and made the most delicious example of that dish I’d ever eaten, even if I do say so myself.

But not everything was perfect. Madame Brassart had crammed too many of us into the class, and Bugnard wasn’t able to give the individual attention I craved. There were times when I had a penetrating question to ask, or a fine point that burned inside of me, and I simply wasn’t able to make myself heard. All this had the effect of making me work even harder.

I had always been content to live a butterfly life of fun, with hardly a care in the world. But at the Cordon Bleu, and in the markets and restaurants of Paris, I suddenly discovered that cooking was a rich and layered and endlessly fascinating subject. The best way to describe it is to say that I fell in love with French food—the tastes, the processes, the history, the endless variations, the rigorous discipline, the creativity, the wonderful people, the equipment, the rituals.

I had never taken anything so seriously in my life—husband and cat excepted—and I could hardly bear to be away from the kitchen.

What fun! What a revelation! How terrible it would have been had Roo de Loo come with a good cook! How magnificent to find my life’s calling, at long last!

“Julie’s cookery is actually improving,” Paul wrote Charlie. “I didn’t quite believe it would, just between us, but it really is. It’s simpler, more classical. . . . I envy her this chance. It would be such fun to be doing it at the same time with her.”

My husband’s support was crucial to keeping my enthusiasm high, yet, as a “Cordon Bleu Widower,” he was often left to his own devices. Paul joined the American Club of Paris, a group of businessmen and government officers who met once a week for lunch. Here he met a pump engineer who introduced him to another, smaller group of American men who were wine aficionados. Frustrated that most of our countrymen never bother to learn about even a fraction of the good French vintages, the members of this group pooled their resources and enlisted Monsieur Pierre Andrieu—a commandeur de la Confrérie des Chevaliers du Tastevin (a leading wine-and-food group) and author of Chronologie Anecdotique du Vignoble Français—to explain the wines of each region, answer oenological questions, and advise them on how to pair specific vintages to foods.

Every six weeks or so, the men would meet at a notable restaurant—Lapérouse, Rôtisserie de la Reine Pédauque, La Crémaillère, Prunier—to eat well and drink five or six wines from a given region. Occasionally they went on outings, such as the time they went to the Clos de Vougeot château, in Burgundy, and went through practically all the caves of the Côte d’Or. Paul especially liked this group because it had no formal membership, no leader, no name, and no dues. Each meal cost six dollars, which covered food, wine, and tip—and must have been one of the greatest deals in the history of gastronomy.

II. NEVER APOLOGIZE

BY EARLY NOVEMBER 1949, the gutters were full of wet brown leaves, the air had turned cold, and, now that it was too late to benefit the poor parched farmers, we were spattered with rain almost every day. Then it turned really cold. Luckily, Paul had just bought a new gas radiator for 81. We’d turn the gas up to full blast and sit practically on top of the heater to keep warm in our crazy salon, like a couple of frozen monarchs.

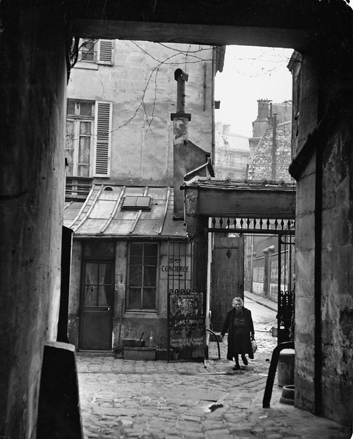

Paris in the cold

Paris was exploding with every kind of exhibit, exhibition, and exposition you could think of—the Salon d’Automne, the automobile show, the Ballet Russe, the Arts, Fruits & Fleurs display, and so on and on. Thérèse Asche and I took a trot through the annual art show in the Palais de Chaillot, and after forty minutes on the cement floor in those drafty galleries our lips had turned blue and our teeth were chattering. We ran out of there and downed a couple of hot grogs to act as antifreeze.

Later, Hélène Baltru reinforced our suspicions that the wet Parisian cold was especially bone-chilling. During the German occupation, she said, Parisians rated their miseries as: first, and worst, the Gestapo; second, the cold; third, the constant hunger.

Hélène’s war story made me think about the French and their deep hunger—something that seemed to lurk beneath their love of food as an art form and their love of cooking as a “sport.” I wondered if the nation’s gastronomical lust had its roots not in the sunshine of art but in the deep, dark deprivations France had suffered over the centuries.

Paul and I were not deprived, but we were hoarding our francs for the months ahead. After I’d written two politically provocative letters to my father, he had not replied. Instead, he’d deposited five hundred dollars in the bank so that I could buy some decent winter clothes. This put me in a quandary. I was grateful for his help, of course, but did I really want to accept his money? Well, I did. But when Pop offered to help launch Paul “into the big time,” we declined politely but firmly.

November 3, 1949, marked our one-year anniversary in Paris. There was a slashing rainstorm that day, just as there had been a year earlier. Looking back, it had been a year of growth. Paul’s personality had enlarged, he’d gained further wisdom, if not salary, and he had continued to expand and refine his artistic vision. I had learned to speak French with some degree of success, though I was not yet fluent, and I was making progress in the kitchen. The sweetness and generosity and politeness and gentleness and humanity of the French had shown me how lovely life can be if one takes time to be friendly.

But I was bothered by my lack of emotional and intellectual development. I was not as quick and confident and verbally adept as I aspired to be. This was obvious the night we had dinner with our American friends Winnie and Ed Riley. Winnie was a naturally warm person; Ed was ruggedly attractive, a successful businessman who held strong conservative opinions. When we got into a discussion about the global economy, I got my foot in my backside and ended up feeling confused and defensive. Under pressure from Ed, my “positions” on important questions—Is the Marshall Plan effectively reviving France? Should there be a European Union? Will socialism take hold in Britain?—were revealed to be emotions masquerading as ideas. This would not do!

Upon reflection, I decided I had three main weaknesses: I was confused (evidenced by a lack of facts, an inability to coordinate my thoughts, and an inability to verbalize my ideas); I had a lack of confidence, which caused me to back down from forcefully stated positions; and I was overly emotional at the expense of careful, “scientific” thought. I was thirty-seven years old and still discovering who I was.

ONE DAY, my sister and I were practicing how to sound French on the telephone so that no one could tell it was us. Dort held her nose with thumb and forefinger pinched over the nostrils, and in a very high, shrill voice said, “Oui, oui, J’ÉCOUTE!,” just as Parisiennes always did. Minette, who was sleeping on a flowerpot, suddenly shot up, pounced onto Dort’s lap, and gave her hand a little love-bite. We thought this was great, so I gave it a try—“Oui, oui, J’ÉCOUTE!”—and it had the same thrilling effect on Mini. This led to more laughter and “J’ÉCOUTE!”s and love-bites. Our high notes must have plucked a mysterious feline chord of amorous response.

Dort had quickly made friends in the expat community, and had landed a job in the business office of the American Club Theatre of Paris. It was an amateur troupe, run by a tough woman from New York. They performed at the Théâtre Monceau, which held about 150 people. The actors were a high-strung and emotional lot, and Dort faced a good deal of strain and long, poorly paid hours. Paul did not love the troupe, because its members liked to show up at Roo de Loo late at night, make noise, and drink rivers of our booze.

But Dort continued to amuse and amaze us. One evening, her friend Annie arrived at our apartment looking flustered. “I was on the metro, and a man pinched me on the derrière,” she said. “I didn’t know how to react. What would you do?”

“I’d say, ‘PardonNEZ, m’sieur!’ ” offered Paul.

“I’d kick him in the balls,” cracked Annie’s boyfriend, Peter.

Dort chimed in: “I’d say, ‘Pardonnez, m’sieur,’ and then kick him in the balls!”

One day, my sister was driving through the Place de la Concorde in her Citroën when a Frenchman rammed her bumper. It wasn’t much of a bump, and the man sped off without bothering to see if he’d done any damage. Dort was enraged by the man’s callous insensitivity. Lights flashing, horn tooting, engine revving, and tires squealing, she gave chase. Finally, about ten blocks later, she managed to corner the man in front of a flic (a cop). Standing up through the Citroën’s open sunroof, my six-foot-three-inch, red-cheeked sister pointed a long, trembling finger at the perpetrator and with maximum indignation yelled: “Ce merde-monsieur a justement craché dans ma derrière!” Her intended meaning is obvious, but what she said was: “This shit-man just spat out into my butt!”

PAUL LOVED WINE, but as a poor artist in the 1920s he had not been able to afford the good stuff. Now he had discovered the wine merchant Nicolas, who had access to an unusually broad and deep selection of vintages, some of which had been buried during the war, hidden from the hated boches. Nicolas had posted a sign in his shop that sternly warned: “Because of the rarity of the wines on this list we’ll accept orders only for immediate use and not for stocking a cave. We will reduce orders we think are excessive.” Nicolas rated his vintages from “very good” (such as a 1926 bottle of Clos-Haut-Peyraguey, for four hundred francs) to “great” (a 1928 bottle of La Mission Haut-Brion, for six hundred francs) to “very great” (a 1929 bottle of Chambertin Clos de Bèze, for seven hundred francs). I was amused by Nicolas’s further notes on “exceptional bottles” (an 1899 Château La Lagune, for eight hundred francs) and bouteilles prestigieuses (an 1870 Mouton Rothschild, for fifteen hundred francs). Nicolas himself would deliver the better bottles in a warmed basket one hour before serving time.

Paul admired such attention to detail. An inveterate organizer himself, he used Nicolas’s lists as a model to draw up his own elaborate charts of wines, their vintages, and costs, which he and his friends would study for hours.

BY THE END OF November, I was shocked to realize that I’d already been at the Cordon Bleu for seven weeks. I had been having such fun that it had whizzed by in what felt like a matter of days. By this point, I could whip up a pretty good piecrust and was able to make a whole pizza—from a mound of dry flour to hot-out-of-the-oven pie—in thirty minutes flat. But the more you learn the more you realize you don’t know, and I felt I had just gotten my foot in the kitchen door. What a tragedy it would have been had I stuck to my original six-week class plan. I’d have learned practically nothing at all.

One of the best lessons I absorbed there was how to do things simply. Take roast veal, for example. Under the tutelage of Chef Bugnard, I simply salt-and-peppered the veal, wrapped it in a thin salt-pork blanket, added julienned carrots and onions to the pan with a tablespoon of butter on top, and basted it as it roasted in the oven. It couldn’t have been simpler. When the veal was done, I’d degrease the juices, add a bit of stock, a dollop of butter, and a tiny bit of water, and reduce for a few minutes; then I’d strain the sauce and pour it over the meat. The result: an absolutely sublime meal.

It gave me a great sense of accomplishment to have learned exactly how to cook such a savory dish, and to be able to replicate it exactly the way I liked, every time, without having to consult a book or think too much.

Chef Bugnard was a wonder with sauces, and one of my favorite lessons was his sole à la normande. Put a half-pound of sole fillets in a buttered pan, place the fish’s bones on top, sprinkle with salt and pepper and minced shallots. Fill the pan with liquid just covering the fillets: half white wine, half water, plus mussel and oyster juices. Poach. When the fillets are done, keep them warm while you make a roux of butter and flour. Add half of the cooking juices and heat. Take the remaining cooking juices and reduce to almost nothing, about a third of a cup. Add the reduced liquid to the roux and stir over heat. Then comes Bugnard’s touch of genius: remove the pan from the fire and stir in one cup of cream and three egg yolks; then work in a mere three-quarters of a pound of butter. I had never heard of stirring egg yolks into such a common sauce, but what a rich difference they made.

Oh, crise de foie, that French sole was so delicious!

ONCE A WEEK, most quartiers in Paris lost their power for a few hours. Paul and I were lucky enough to live next to the Chambre des Députés, and so were spared the blackouts by some kind of special political dispensation. But on most Wednesdays, there was no electricity in the Cordon Bleu’s quarter. These powerless Wednesdays forced Chef Bugnard to be creative with our classtime. Often he’d take us to the market, an experience that was worthy of a graduate degree unto itself.

Indeed, shopping for food in Paris was a life-changing experience for me. It was through daily excursions to my local marketplace on la Rue de Bourgogne, or to the bigger one on la Rue Cler, or, best of all, into the organized chaos of Les Halles—the famous marketplace in central Paris—that I learned one of the most important lessons of my life: the value of les human relations.

The French are very sensitive to personal dynamics, and they believe that you must earn your rewards. If a tourist enters a food stall thinking he’s going to be cheated, the salesman will sense this and obligingly cheat him. But if a Frenchman senses that a visitor is delighted to be in his store, and takes a genuine interest in what is for sale, then he’ll just open up like a flower. The Parisian grocers insisted that I interact with them personally: if I wasn’t willing to take the time to get to know them and their wares, then I would not go home with the freshest legumes or cuts of meat in my basket. They certainly made me work for my supper—but, oh, what suppers!

One Wednesday, Chef Bugnard took us to Les Halles in search of provisions for upcoming classes: liver, chickens, beef, vegetables, and candied violets. We made our way through a wonderful hodgepodge of buildings, each filled with food stalls and purveyors of cooking equipment. You could find virtually anything under the sun there. As we dodged around freshly killed rabbits and pig trotters, or large men unpacking crates of glistening blue-black mussels and hearty women shouting about their wonderful champignons, I avidly jotted down notes about who carried what and where they were located, worried that I’d never be able to find them again in the raucous maze.

Eventually we arrived at Dehillerin. I was thunderstruck. Dehillerin was the kitchen-equipment store of all time, a restaurant-supply house stuffed with an infinite number of wondrous gadgets, tools, implements, and gewgaws—big shiny copper kettles, turbotières, fish and chicken poachers, eccentrically shaped frying pans, tiny wooden spoons and enormous mixing paddles, elephant-sized salad baskets, all shapes and sizes of knives, choppers, molds, platters, whisks, basins, butter spreaders, and mastodon mashers.

Seeing the gleam of obsession in my eyes, Chef Bugnard took me aside and introduced me to the owner, Monsieur Dehillerin. I asked him all sorts of questions, and we quickly became friends. He even lent me money once, when I had run out of francs shopping at Les Halles and the banks were all closed. He knew I’d repay him, as I was one of his steadiest customers. I had become a knife freak, a frying-pan freak, a gadget freak—and, especially, a copper freak!

“ALL SORTS OF délices are spouting out of [Julia’s] finger ends like sparks out of a pinwheel,” Paul enthused to Charlie. “The other night, for guests, she tried out a dessert she’d seen demonstrated . . . a sort of French-style brown betty . . . which turned out very well.”

In spite of my good notices, I remained a long way from being a maître de cuisine. This was made plain the day I invited my friend Winnie for lunch, and managed to serve her the most vile eggs Florentine one could imagine outside of England. I suppose I had gotten a little too self-confident for my own good: rather than measure out the flour, I had guessed at the proportions, and the result was a goopy sauce Mornay. Unable to find spinach at the market, I’d bought chicory instead; it, too, was horrid. We ate the lunch with painful politeness and avoided discussing its taste. I made sure not to apologize for it. This was a rule of mine.

I don’t believe in twisting yourself into knots of excuses and explanations over the food you make. When one’s hostess starts in with self-deprecations such as “Oh, I don’t know how to cook . . . ,” or “Poor little me . . . ,” or “This may taste awful . . . ,” it is so dreadful to have to reassure her that everything is delicious and fine, whether it is or not. Besides, such admissions only draw attention to one’s shortcomings (or self-perceived shortcomings), and make the other person think, “Yes, you’re right, this really is an awful meal!” Maybe the cat has fallen into the stew, or the lettuce has frozen, or the cake has collapsed—eh bien, tant pis!

Usually one’s cooking is better than one thinks it is. And if the food is truly vile, as my ersatz eggs Florentine surely were, then the cook must simply grit her teeth and bear it with a smile—and learn from her mistakes.

III. THE MAD SCIENTIST

IN LATE 1949, the newspapers informed us that something called “television” was sweeping the States like a hailstorm. People across the country, the papers said, were building “TV rumpus-rooms,” complete with built-in bars and plastic stools, in order to sit around for hours watching this magical new box. There were even said to be televisions in buses and on streetcars, and TV advertising in all the subways. It was hard to imagine. There was no TV that we knew of in Paris—we were finding it hard enough to find some decent music on the radio (most of the stations played contemporary stuff, which sounded like music to set the mood on the moors for The Hound of the Baskervilles).

When we read an article about the horrifying effects of TV on American home life, we asked Charlie and Freddie if they had bought a television set yet—they hadn’t—or if they knew anyone who had—no, again. Did our nieces and nephew feel left out of the gang for not having such a machine? “No . . . for the moment.”

IT WAS MID-DECEMBER when Paul wrote his twin:

The sight of Julie in front of her stove full of boiling, frying and simmering foods has the same fascination for me as watching a kettle-drummer at the Symphony. (If I don’t sit and watch I never see Julie.) . . . Imagine this in your mind’s eye: Julie, with a blue denim apron on, a dish towel stuck under her belt, a spoon in each hand, stirring two pots at the same time. Warning bells are sounding off like signals from the podium, and a garlic-flavored steam fills the air with an odoriferous leitmotif. The oven door opens and shuts so fast you hardly notice the deft thrust of a spoon as she dips into a casserole and up to her mouth for a taste-check like a perfectly timed double-beat on the drums. She stands there surrounded by a battery of instruments with an air of authority and confidence. . . .

She’s becoming an expert plucker, skinner and boner. It’s a wonderful sight to see her pulling all the guts out of a chicken through a tiny hole in its neck and then, from the same little orifice, loosening the skin from the flesh in order to put in an array of leopard-spots made of truffles. Or to watch her remove all the bones from a goose without tearing the skin. And you ought to see [her] skin a wild hare—you’d swear she’d just been Comin’ Round the Mountain with Her Bowie Knife in Hand.

Paul took to calling the kitchen my “alchemist’s aerie,” and me “Jackdaw Julie,” after the slightly mad bird that collects every kind of stick, trinket, tidbit, and fluff to outfit its nest with. The fact is, I had been making regular raiding trips to Dehillerin to stock up on all manner of culinary tools and machines. Now our kitchen had enough knives to fill a pirate ship. We had copper vessels, terra-cotta vessels, tin vessels, enamel vessels, crockery and porcelain vessels. We had measuring rods, scales, thermometers, timing clocks, openers, bottles, boxes, bags, weights, graters, rolling pins, marble slabs, and fancy extruders. On one side of the kitchen, standing in a row like fat soldiers, were seven Ali Baba–type oil jars filled with basic reductions. On the other side were measurers—for a liter, demiliter, quarter-liter, deciliters, and demideciliters—hanging from hooks. Tucked all round were my specialty tools: a copper sugar-boiler; long needles for larding roasts; an oval tortoise-shelled implement used to scrape a tamis; a conical sieve called a chinois; little frying pans used only for crêpes; tart rings; stirring paddles carved from maplewood; and numerous heavy copper pot-lids with long iron handles. My kitchen positively gleamed with gadgets. But I never seemed to have quite enough.

One Sunday we went to the Marché aux Puces, the famous flea market on the outer fringes of Paris, in search of something special: a large mortar and pestle used in the preparation of those lovely, light quenelles de brochet (a labor-intensive dish made by filleting fish, grinding it up in the big mortar, forcing it through a tamis sieve, and then beating in cream over a bowl of ice). The Marché aux Puces was a vast, sprawling market where one could buy just about anything. After several hours of hunting through obscure alleys between packing-box houses in remote corners, I managed by some special chien-de-cuisine instinct to run the coveted items to earth. The mortar was made of dark-gray marble, and was about the size and weight of a baptismal font. The pestle looked like a primeval cudgel made from a hacked-off crab-tree limb. One look at it, and I knew there was no question: I just had to have that set. Paul looked at me as if I were crazy. But he knew when I was fixated on something special, and with a shrug and a smile, he pulled out his wallet. Then he took a deep breath, crouched down, and, using every bit of strength and ingenuity, hefted my prize to his shoulder. Staggering back to the Flash with trembling knee and aching lung, he wended his way for miles through the market’s narrow, crowded, flea-bitten passageways. As he eased the mega-mortar and pestle into the car, the old Flash positively slumped and wheezed.

Paul was justly proud of his “slave labor,” and, a week later, he was rewarded by my first-ever quenelles de brochet—delicate, pillowy-light spoonfuls of puréed pike that had been poached in a seasoned broth. Served with a good cream sauce, it was a triumph. In spite of his careful attention to diet, Paul slurped the quenelles up hungrily.

I was really getting into the swing of things now. Over a period of six weeks, I made: terrine de lapin de garenne, quiche Lorraine, galantine de volaille, gnocchi à la Florentine, vol-au-vent financière, choucroute garni à l’Alsacienne, crème Chantilly, charlotte de pommes, soufflé Grand Marnier, risotto aux fruits de mer, coquilles Saint-Jacques, merlan en lorgnette, rouget au safron, poulet sauce Marengo, canard à l’orange, and turbot farci braisé au champagne.

Whew!

Paul’s favorite belt was an old leather job that he’d picked up in Asia during the war. In August it was notched at the number-two hole, and he weighed an all-time high of 190 pounds. With great difficulty he forced himself to cut down on his carbohydrates and, most significantly, on his alcohol intake. He also started attending exercise classes, where he’d throw heavy medicine balls around with men half his age. By December, the belt notched right into the number-five hole, indicating a new svelteness of 170 pounds. I admired his self-discipline. Yet, in spite of his robustness, Paul was often plagued by poor health. Some of his problems, such as his sensitive stomach, were the result of amoebic dysentery from the war; others were the result of his jumpy nerves. (His brother never had a physical exam, because he figured Paul would take care of all the worry and ailments; indeed, Charlie hardly ever got sick.)

As boys, Paul and Charlie used to wrestle each other, race, climb steep walls, and generally attempt to outdo one another in feats of derring-do. In quieter moments, the twins invented games with whatever was lying around the house. One of their favorites was the “sewing” game, in which they used a real needle and thread. One day when they were seven years old, Charlie was sewing and Paul leaned over his brother’s shoulder to see what he was doing. Just then, the needle came rising up in Charlie’s hand and went straight into Paul’s left eye. It was a terrible accident. Paul had to wear a black patch for a year, and lost the use of that eye. But he never complained about his handicap, could drive a car perfectly, and learned to paint so well that he taught perspective.

OFF TO ENGLAND for Christmas! We stayed with our friends the Bicknells in Cambridge: Peter was a don of architecture at the university, a mountaineer, and a lovely fellow with a big mustache; Mari was a good cook, had studied ballet with Sadler’s Wells, and now taught ballet to children; they had four children, and loved French food. We shared a pre-Christmas feast in the kitchen together, with a menu of sole bonne femme, roasted pheasant, soufflé Grand Marnier, and great wines—including a Château d’Yquem 1929 with the soufflé.

From there to jolly old London, where we walked and ate all over town, then to Newcastle, and finally to a friend’s farm in Hereford. The countryside was poetic, filled with such great trees, cows, hedges, and thatched-roof cottages that I felt compelled to read Wordsworth. But the public food was every bit as awful as our Parisian friends had warned us it would be.

One evening, we stopped at a charming Tudor inn, where we were served boiled chicken, with little feathers sticking out of the skin, partially covered with a typical English white sauce. Aha! At last I would try the infamous sauce that the French were so chauvinistic about. The sauce was composed of flour and water (not even chicken bouillon) and hardly any salt. It was truly horrible to eat, but a wonderful cultural experience.

I admired the English immensely for all that they had endured, and they were certainly honorable, and stopped their cars for pedestrians, and called you “sir” and “madam,” and so on. But after a week there, I began to feel wild. It was those ruddy English faces, so held in by duty, the sense of “what is done” and “what is not done,” and always swigging tea and chirping, that made me want to scream like a hyena. The Old Sod never laid a haunting melody on me gut strings.

In a way, I felt that I understood England intuitively, because it reminded me of visiting my relatives in Massachusetts, who were much more formal and conformist than I was.

My mother, Caro, with me and John

My mother, Julia Carolyn Weston (Caro), was one of ten children (three of whom died) raised in prosperous surroundings in Dalton, Massachusetts. The Westons could trace their roots back to eleventh-century England, and had lived in Plymouth Colony. Mother’s father had founded the Weston Paper Company in Dalton, was a leading citizen in western Massachusetts, and had served as the state’s lieutenant governor.

My father’s family was of Scottish origin. His father, also called John McWilliams, came from a farming family near Chicago; he left the farm as a sixteen-year-old to pan for gold in California during the covered-wagon days. He invested in California mineral rights and Arkansas rice fields, and retired to Pasadena in the 1890s. He lived to be ninety-three. His wife, Grandmother McWilliams, was a great cook who made delicious broiled chicken and wonderful doughnuts. She was from Illinois farm country, and in the 1880s her family had a French cook—something that was fairly common at the time.

My mother was in the class of 1900 at Smith, where she was captain of the basketball team and was known for her wild red hair, outspoken opinions, and sense of humor. My father—tall, reserved, athletic—graduated in the class of 1901 from Princeton, where he studied history. My parents met in Chicago in 1903 and, after marrying in 1911, settled in Pasadena, where my father took over his father’s land-management business. I was born on August 15, 1912; my brother, John McWilliams III, was born in 1914; and Dorothy was born in 1917. As children, we’d occasionally travel east to visit our many aunts, uncles, and cousins in Dalton and Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where I learned about my New England roots.

I was enrolled at Smith College at birth, and eventually graduated from there in 1934, with a degree in history. My upper-middle-brow parents weren’t intellectual at all, and I had no exposure to eggheads until the war. At Smith I did some theater, a bit of creative writing, and played basketball. But I was a pure romantic, and only operating with half my burners turned on; I spent most of my time there just growing up. It was during Prohibition and in my senior year a bunch of us piled into my car and drove to a speakeasy in Holyoke. It felt so dangerous and wicked. The speakeasy was on the top floor of a warehouse, and who knew what kind of people would be there? Well, everyone was perfectly nice, and we each drank one of everything, and on the drive home most of us got heartily sick. It was terribly exciting!

My plan after college was to become a famous woman novelist. I moved to New York and shared a tiny apartment with two other girls under the Queensboro Bridge. But when Time, Newsweek, and The New Yorker did not offer me a job, for some reason, I went to work in the advertising department of the W. & J. Sloane furniture store. I enjoyed it, at first, but I was only making twenty-five dollars a week and living in tight, camping-out circumstances. In 1937, I returned to Pasadena, to help my ailing mother; two months later, she died of high blood pressure. She was only sixty.

I kept house for my father, did some volunteer work for the Red Cross, and generally felt like I was drifting. I knew I didn’t want to become a standard housewife, or a corporate woman, but I wasn’t sure what I did want to be. Luckily, Dort had just returned home from Bennington, so, while she watched Pop, I headed east, to Washington, D.C., where I had friends. Then the war broke out, and I wanted to do something to aid my country in a time of crisis. I was too tall for the WACs and WAVES, but eventually joined the OSS, and set out into the world looking for adventure.

I could at times be overly emotional, but was lucky to have the kind of orderly mind that is good at categorizing things. After working on an air-sea rescue unit, where we developed a signal mirror for downed pilots and had a “fish-squeezing” department trying to create a shark repellent, I was posted to Ceylon as the head of the Registry, where I kept files and processed highly secret material from our agents.

As for Paul, he, Charlie, and their sister, Meeda, who was two years older than the twins, were raised in Brookline, Massachusetts, in the countryside outside of Boston. Their father, Charles Tripler Child, was an electrical engineer, who died of typhoid fever in 1902, when the boys were only six months old. Their mother, Bertha Cushing Child, was a concert singer, a theosophist, and a vegetarian. In those days, widows had few opportunities to find decent work, but she was beautiful, had long honey-blond hair and a splendid voice.

There was a tradition of “gentle” entertaining in private homes—poetry readings, lectures, spiritual sessions, and so forth. Paul played the violin and Charlie played the cello; with Meeda on piano, they performed together as “Mrs. Child and the Children.” At that time, Brookline swarmed with new Irish, Italian, and Jewish immigrants, and gangs were common. One day, teenage Paul and Charlie, dressed in gray flannel suits (which they loathed) and carrying their instruments, were jumped by a band of thugs as they walked to a recital. But the Child boys had learned judo from the Japanese butler of a friend, and stood their ground. Years later, Charlie wrote: “Swinging our instruments around like clumsy battle-axes and screaming a series of bloodcurdling oaths . . . we went into battle. Twang! went the fiddle on someone’s skull. . . . Whomp! went the cello. . . . Like two berserk Samurai . . . we charged into the howling enemy.” Paul and Charlie emerged victorious. But when they greeted their mother with ripped suits, bloody noses, and crushed instruments, that was the end of “Mrs. Child and the Children”!

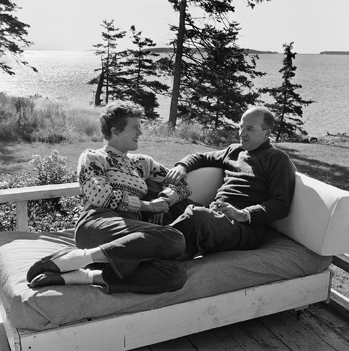

Charlie and Paul

Despite his lack of a college education, I considered Paul an intellectual, in the sense that he had a real thirst for knowledge, was widely read, wrote poetry, and was always trying to train his mind. We met in Ceylon, in 1944. Paul had come down from Delhi, India, to head the OSS’s Visual Presentation group in Kandy, where he created a secret war room and maps of places like the Burma Road, for General Mountbatten.

We were based at a lovely old tea plantation, and I could look out my office window into Paul’s office. I was still unformed. He was ten years older than me and worldly; he courted various other women there, but we slowly warmed up to each other. We took trips to places like the Temple of the Tooth, or elephant rides into the bush (one elephant knew how to turn on faucets for a drink of water), and we shared an interest in the local food and customs. Unlike most of the U.S. Army types, our OSS colleagues were a fascinating bunch of anthropologists, geographers, missionaries, psychiatrists, ornithologists, cartographers, bankers, and lawyers. They were genuinely interested in Ceylon and its people. “Aha!” I said to myself. “Now, here’s the kind of person I’ve been missing my whole life!”

After Ceylon, Paul was assigned to Chungking, then Kunming, China, where he designed war rooms for General Wedemeyer. I was also assigned to Kunming, where I fixed up the OSS files. By this point we were becoming a couple. We loved the earthy Chinese people and their marvelously crowded and noisy restaurants, and we spent a lot of our off-hours exploring different types of regional foods together.

Back in the States after the war, we took a few months to get to know each other in civilian clothes. We visited Pop and his second wife, Phila, in Pasadena, then drove across the country and stayed with Charlie and Freddie in Maine. It was the summer of 1946; I was about to turn thirty-four and Paul was forty-four. After a few days there, we took deep breaths and announced: “We’ve decided to get married.”

“About time!” came the reply from Charlie and Freddie.

In September 1946 we married—extremely happy, but a bit banged up from a car accident the day before.

WHEN PAUL AND I returned to Paris from England to celebrate the new year, 1950, I almost wept with relief and pleasure. Oh, how I adored sweet and natural France, with its human warmth, wonderful smells, graciousness, coziness, and freedom of spirit!

Paris was full of specialized things to buy at that time of year. Hermès was one of the best-known shops for “people who have everything.” I longed for a few of their famous but frightfully expensive scarves. The store was so chic that I’d only dared to venture inside twice. Even when dressed in my very best clothes and with a lovely hat on, I felt like an old frump in those luxe surroundings.

I wanted to look chic and Parisian, but with my big bones and long feet, I did not fit most French clothes. I’d dress in simple, American-made skirts and blouses with a thin sweater and canvas sneakers. Many times, I had to mail-order things from the States, especially if I wanted, say, a smart pair of shoes. One night, my friend Rosie (Rosemary Manell)—another big-boned California girl—and I got dressed up for a fancy party at the U.S. Embassy. We had expensive hairdos, put on our nicest dresses, chicest hats, and best makeup. Then we looked at each other. “Pretty good,” we declared, “but not great.” We had tried, and this was the very best we’d ever look.

THE CORDON BLEU got back in full swing in the first week of 1950. In thinking about all I had learned since October, I realized that it had taken a full two months of near-total immersion for the teaching to take hold. Or begin to take hold, I should say, because the more I learned the more I realized how very much one has to know before one is in-the-know at all.

I could finally see how to cook properly, for the first time in my life. I was learning to take time—hours, even—and care to present a delicious meal. My teachers were fanatics about detail and would never compromise. Chef Bugnard drilled into me the necessity of proper technique—such as how to “turn” a mushroom correctly—and the importance of practice, practice, practice. “It’s always worth the effort, Madame Scheeld!” he’d say. “Goûtez! Goûtez!” (“Taste! Taste!”)

Of course, I made many boo-boos. At first this broke my heart, but then I came to understand that learning how to fix one’s mistakes, or live with them, was an important part of becoming a cook. I was beginning to feel la cuisine bourgeoise in my hands, my stomach, my soul.

When I wasn’t at school, I was experimenting at home, and became a bit of a Mad Scientist. I did hours of research on mayonnaise, for instance, and although no one else seemed to care about it, I thought it was utterly fascinating. When the weather turned cold, the mayo suddenly became a terrible struggle, because the emulsion kept separating, and it wouldn’t behave when there was a change in the olive oil or the room temperature. I finally got the upper hand by going back to the beginning of the process, studying each step scientifically, and writing it all down. By the end of my research, I believe, I had written more on the subject of mayonnaise than anyone in history. I made so much mayonnaise that Paul and I could hardly bear to eat it anymore, and I took to dumping my test batches down the toilet. What a shame. But in this way I had finally discovered a foolproof recipe, which was a glory!

I proudly typed it up and sent it off to friends and family in the States, and asked them to test it and send me their comments. All I received in response was a yawning silence. Hm! I had a great many things to say about sauces as well, but if no one cared to hear my insights, then what was the use of throwing perfectly good béarnaise and gribiche down a well?

I was miffed, but not deterred. Onward I plunged.

I made the lovely homard à l’américaine—a live lobster cut up (it dies immediately), and simmered in wine, tomatoes, garlic, and herbs—twice in four days, and spent almost all of another day getting the recipe for that dish in good shape. I was striving to make my version absolutely exact and clear, which was excellent practice for whatever my future in cooking might be. My immediate plan was to develop enough foolproof recipes so that I could begin to teach classes of my own.

Immersed in cookery, I found that deeply sunk childhood memories had begun to bubble up to the surface. Recollections of the pleasant-but-basic cooking of our hired cooks in Pasadena came back to me—the big hams or gray roast beef served with buttery mashed potatoes. But then, unexpectedly, so did yet deeper memories of more elegant meals prepared in a grand manner by accomplished cooks when I was just a girl—such as wonderfully delicate and sauced fish. As a child I had barely noticed these real cooks, but now their faces and their food suddenly came back to me in vivid detail. Funny how memory works.

IV. FIRST CLASS

THE WALLS ACROSS the street from the Roo de Loo were plastered with screaming yellow posters claiming that the “Imperialistic Americans” were trying to take over the French government: “Strike for Peace!,” etc.

So icy was the Cold War now that Paul and I were half convinced that the Russians—“the wily Commies,” he called them—would invade Western Europe. He suffered nightmares over the possibility of an all-out nuclear war. He grew snappish at the office, convinced that the busywork that ate up his days was trivial in light of our nation’s unpreparedness. I declared that I was ready to man the barricades to defend la belle France and her wonderful citizens, like Madame Perrier, Hélène Baltrusaitis, Marie des Quatre Saisons, and Chef Bugnard!

Much of the American press, meanwhile, denounced the French for “just sitting there, doing nothing about the Communists, and looking for appeasement in Indo-China.” But this was absurd. France was still in a state of post-war shock: she had lost hundreds of thousands of men during the German occupation, had only minimal industrial production, and had a large and well-organized Communist fifth column to deal with. And now she was mired in a sticky and disheartening war in Indochina. The government of France believed it was “saving the lives of all other non-Communist nations” by fighting for the rice paddies there. But the war was proving expensive and unpopular. In fact, the U.S.A. was furnishing arms to France, which allowed the war to continue and brewed up an anti-American sentiment in the streets. There was a rash of strikes and troubles throughout the country. It was easy for Americans to criticize from afar, but I didn’t see what other course of action the French could take: they had to muddle through their turmoil, day to day, and hope for the best.

Phila and Pop

My parents, Big John and Phila, collectively known as “Philapop,” were among those who liked to criticize France without any real understanding of the country. Dort and I were determined to change that, and had invited them to visit. Our goal was to show them a bit of the life and people that we found so heartwarming and satisfying. Then we’d tour Italy with them. (Paul didn’t want to use his precious vacation time on his in-laws, and I can’t say I blamed him.)

When they arrived and settled in at the Ritz, my father looked like un vieillard, an old man, which he never used to be. He’d launch into long speeches in English about American business and agriculture, leaving our French friends mystified. He and Phila ate simply so as to avoid any stomach trouble. My sister and I had been prepared for the worst, but Philapop were surprisingly mellow and lovely.

On April 10, the four of us McWilliamses began a slow drive toward Naples. The main French highways were filled with madly driven trucks, and people with their noses buried in their Michelin guides, so we stuck to side roads. As we reached the Mediterranean, we Californians all responded to the colors and palm trees and waves.

But this wasn’t real travel, as I saw it. Phila liked to go to all the gay places she’d read about in American magazines, but she didn’t really care where we were. Pop was interested in how the French made money, and he preferred the country to cities, but he was stiff in the joints and couldn’t walk much, and had zero interest in ruins or culture or food or wine. When we roared past the Roman arch at Orange, he mumbled, “Oh yes, Roman, you say? Hmm.”

Dort and I grew restless on those days of driving and driving and eating and driving and eating at the biggest-best restaurants and sleeping at the biggest-best hotels. To hell with it! It seemed like we’d never really been anywhere or done anything and the whole point of the trip was for Philapop to get back to Pasadena and say, “I’ve just been through France and Italy.” In fact, I didn’t like traveling first-class at all. Yes, it was nice to have a bathroom in the hotel and fine service at breakfast, and I’d probably never visit those grand hotels again, but none of it seemed foreign enough to me. It was all so pleasantly bland that it felt as if I were back on the SS America. I don’t like it when everyone speaks perfect English; I’d much rather struggle with my phrase book.

One exception was the Hôtel de Paris, in Monte Carlo. It was an enormous, old-fashioned, ornate building across from the Casino. What a treat! It had a splendid Louis XVI–style dining room, with black-and-white Carrara-marble pillars, gilt molding, Cupids, murals of virginal nudes willowing about forest-glen fountains, splendiferous eighty-foot chandeliers, a string orchestra playing Viennese waltzes, and so on. In detail it sounds insane, but the effect was nostalgic elegance. Our dinner there was superb, and the service—provided by a headwaiter, two sub-headwaiters, two waiters, and a busboy for each table—was faultless. It made us feel as if we had been transported back in time to the Gilded Age.

Italy was nice, with a tremendous shining yacht in the harbor at Portofino, except that the entire coast was still shot up from the war. Even the big Autostrada from Pisa to Florence remained a wreck, with many bridges and overpasses not yet repaired. The country seemed poverty-stricken. The food didn’t strike me as anything special, either; it didn’t have much finesse. Maybe that’s why Italy didn’t hit me with the same vibrations that France did. Or maybe it was because I hated being without my husband.

Paul and I liked to travel at the same slow pace. He always knew so much about things, discovered hidden wonders, noticed ancient walls or indigenous smells, and I missed his warm presence. Once upon a time I had been content as a single woman, but now I couldn’t stand it!

I really wanted Philapop to enjoy their super-deluxe trip, though, and I was trying my damnedest to be the way they wanted me to be: nice and amenable and dumb, with no thoughts or feelings about anything.

We whizzed through Florence, Rome, Sorrento, Naples, and Lake Como. After thirty minutes at the Pitti Palace, Pop announced he was “educated.” The poor man couldn’t wait to return to California. “I can’t talk to these people, I just poke around the streets,” he grumbled. “I’m so happy at home, where I’ve got my nice house, my friends, and I can talk the language.” It struck me how utterly divorced I had become from old Pop and his type—moneyed, materialistic, not at all introspective—and how profoundly, abysmally, stupefyingly apathetic his world-view had rendered me. No wonder I had been so immature at Smith!

When we returned to Paris on May 3, I fell into Paul’s arms and squeezed him tight.

BACK AT THE Cordon Bleu, I picked up my routine again, beginning at 6:30 a.m. and ending around midnight every weekday. But I was growing increasingly dissatisfied with the school. The $150 tuition was expensive. Madame Brassart paid little attention to the details of management. Many of the classes were disorganized, and the teachers lacked basic supplies. And after six months of intensive instruction, not one of the eleven GIs in my class knew the proportions for a béchamel sauce or how to clean a chicken the right way. They just weren’t serious, and that irritated me.

Even Chef Bugnard was beginning to repeat such dishes as sole normande, poulet chaud-froid, omelettes, and crêpes Suzettes. It was useful practice to do these dishes over and over, and at last I could make a decent piecrust without thinking twice. But I wanted to be pushed harder and further. There was so much more to learn!

Bugnard, I suspect, had been quietly monitoring my progress, and had now gained enough confidence in me that he began to take me aside and show me things that he didn’t show “the boys.” This time when he took me around Les Halles, he personally introduced me to his favorite meat, vegetable, and wine purveyors.

I decided to give up the Cordon Bleu for the time being. I didn’t want to lose my momentum, though, so I continued to attend the afternoon demonstrations (a dollar each), and go to as many of the pâtisserie demonstrations ($1.99 per class) as I could. In the meantime, I was constantly experimenting on the stove at home. On the QT, Chef Bugnard joined me at 81 for an occasional private cooking lesson.

One of the things I loved about French cooking was the way that basic themes could be made in a seemingly infinite number of variations—scalloped potatoes, say, could be done with milk and cheese, with carrots and cream, with beef stock and cheese, with onions and tomatoes, and so on and on. I wanted to try them all, and did. I learned how to do things professionally, like how to fix properly a piece of fish in thirteen different ways, or how to use the specialized vocabulary of the kitchen—“petits dés” are vegetables “diced quite finely”; a douille is the tin nozzle of a pastry bag that lets you squeeze a cake decoration as the icing blurps out.

There was, in fact, a method to my madness: I was preparing for my final examination. I could take it anytime I felt ready to, Madame Brassart said, and I was determined to do as well as possible. After all, if I were going to open a restaurant or a cooking school, what better credentials could I have than the Cordon Bleu, of Paris, France?

I knew that I’d have to keep honing my skills until I had all of the recipes and techniques down cold and could perform them under pressure. The exam didn’t intimidate me. In fact, I looked forward to it.

V. BASTILLE DAY

“ÇA Y EST! C’EST FAIT! C’est le quator-zuh juillet!” That revolutionary ditty has a catchy swing to it in French, but is quite meaningless in a literal translation. I render it as something like “Hooray, we did it! The Fourteenth of July!”

Oh, the fury of the French Revolution, where the people of the streets rushed at the hated symbols of the King, especially the Bastille prison, which they tore down, stone by stone, and distributed all over the city. Some of those stones were built into the foundation of 81 Rue de l’Université.

In the summer of 1950, Charlie and Freddie and their three children—Erica, Rachel, and Jon—had finally come to visit us. It was a dream come true to spend time together in Paris. In the meantime, Paul and I had hired a new femme de ménage. I had once pictured French maids as chic creatures in starched white aprons—shades of Vogue magazine. Coo-Coo had changed that perception, and now our latest, Jeanne, shattered it forever. She was a tiny, slightly wall-eyed, frazzle-haired woman with a childish mind that often wandered astray.

Jeanne was a hard worker and unfailingly faithful; she and Minette became fast friends, and when we hosted parties she became even more excited than we did. But we called her “Jeanne-la-folle” (“crazy Jeanne”), because she looked rather mad, and sometimes acted it, too.

“Jeanne-la-folle”

At the height of the summer, all of the toilets in the house suddenly stopped flushing. This being dear old Paris, we couldn’t find a plombier willing to rush over. Finally, after a few uncomfortable days, help arrived. After much sweat and toil over our toilet waste-pipe, the plumber discovered an American beer can lodged deeply inside. When I asked Jeanne-la-folle if she had flushed it down the toilet, she replied, “Mais oui—je rejete TOUJOURS les choses dans les toilettes! C’est beaucoup plus facile, vous savez.” Hm. Cost of repair: a hundred dollars.

On the evening of Bastille Day, July 14, we planned a special buffet dinner to precede the traditional fireworks. The pièce de résistance of our meal would be a ballottine of veal: veal that has been stuffed and rolled into the shape of a log and served hot with a luscious sauce. Two days before the feast, Jeanne-la-folle and I prepared a goodly amount of perfect, Escoffier-type veal stock for poaching the ballottine. It was the best and most careful stock I had ever made. Next we prepared an elaborate veal forcemeat that included quite a generous bit of foie gras, mushroom duxelles, Cognac, Madeira, and blanched chard leaves which would be used to make a nice pattern. We then stuffed the veal with the forcemeat, tied it up ever so neatly in its clean poaching cloth, and refrigerated it for the following day. I also used some of the veal stock to simmer up a first-class truffled Madeira sauce. The night of the thirteenth, we readied everything that could be readied, for Jeanne was setting off to celebrate the national holiday with her family in the country. She was so excited about our party that she hardly slept.

The morning of July 14, the seven of us Childs got ourselves up and out to the parade route early. We trooped over the Concorde Bridge and up the Champs-Élyseés to stand strategically in the front row, just beyond the Rond-Point. Fortunately, we were there in good time, before too much of a crowd had gathered along the avenue. Eventually we heard the martial music, and the troops began to sweep down the Champs in waves. There were tootling military bands of various sorts, regiments of smartly garbed French foot soldiers, groups of camels, colorful African troops in native costume on handsome horses, and French cavalry officers in elaborate uniforms, their horses prancing high. Now and then a cannon would trundle by, and a gaggle of fighter planes would swoop down and pass right over us with a deafening roar.

The crowd cheered, clapped, and ooh-la-la-ed at each passing display. It was a real parade, a lively and seemingly spontaneous outpouring of patriotic glee. Erica and Rachel and Jon were delighted by the spectacle and the foreignness of it all.

That evening we held our party, an informal group of about twenty people, at our apartment. A few were relics of the old days, before my time, when Paul, Charlie, and Freddie had been bohemians in the Paris of the 1920s. One such couple were Samuel and Narcissa Chamberlain. He was an etcher, a food writer, and author of Clementine in the Kitchen, the charming memoir of an American family living in a French village with a super femme de ménage, Clementine, who was also a great cook. Narcissa collaborated with her husband and acted as his recipe developer. Another visitor that night was a fleeting, wrenlike person in a tan pongee accordion-pleated skirt and wide-brimmed pongee-colored hat. She was so small that the hat hid her face until she looked up and you noticed that it was Alice B. Toklas. She always seemed to be popping up in Paris like that. She stayed only for a glass of wine before dinner.

After a decent amount of champagne and toasts, we dove into the large buffet. The ballottine, poached in the spectacular veal stock and then allowed to linger in it a while to enhance the flavor, was an immense success with its truffled sauce. Watching my family and friends happily enjoy the meal, savoring every drop of that poaching stock, which had been further enriched by the complex flavors of the ballottine, I secretly bestowed upon myself a French culinary compliment of the highest order: “impeccable.”

But the fireworks would soon begin! After dinner, and a dessert of a beautiful meringue-ringed chocolate-mousse cake that I had bought from the very chic pastry shop near us on la Rue du Bac, we rushed through a quick preliminary cleanup. Charlie and Paul insisted that the rest of us stay downstairs in the salon, while they took on the piles of dishes in the third-floor kitchen. When they reappeared, red in the face from exertion, we headed up to Montmartre to view the evening’s display.

The event started off in a leisurely fashion, one rocket at a time arcing through the sky, giving us time to savor their artistry. The crowd oohed with pleasure at the glittering sparks. The pace gradually quickened, until a bouquet of rapid detonations gave way to the three tremendous cannon booms of the finale. The crowd fell into an awed silence. Then there were sighs of satisfaction, as people began to disperse into the warm night. It felt as if France herself was finally stirring again, and shucking off the nightmares of war.

We joined the throng of celebrants walking down the Montmartre hill. As the young were bedded down at home, I went up to the kitchen for the final cleanup. The boys had done a splendid job of scraping and stacking plates in our vast stoneware sink. But where had they put all the garbage? My eyes darted this way and that. After poaching the ballottine, I had set my big stockpot on the floor, to cool off. Eyeing it with a sense of foreboding now, I just knew: they had dumped it all in there—into my precious, wonderful, unique, never-to-be-equaled veal stock!

I sighed. There was no undoing what had been done, and I could only sob in my innermost self. I vowed never to mention it—or forget it.

VI. AN AMERICAN STOMACH IN PARIS

BY SEPTEMBER 1950, Paul was suffering from mystery pains in his chest and back, not sleeping well, and feeling nauseated all the time. Generally, he let his afflictions ride themselves out. But this time they wouldn’t quit. The embassy doctor diagnosed Paul with some kind of “local condition” of heart and strained nerves, probably the effects of a long-ago judo accident. “Could be,” said Paul, with a shrug, sounding unconvinced.

He went to a French doctor, Dr. Wolfram, who happened to be a tropical-disease specialist. Wolfram looked at Paul’s medical reports dating back to Ceylon, China, and Washington, D.C., which all said there was no evidence of tropical disease. But after measuring Paul’s liver and spleen, Wolfram said that Paul’s symptoms matched the amoebic dysentery he’d seen in French colonials. The sharp mystery-pains in the chest and back were probably the result of gas buildup from the bugs in Paul’s gut. Paul was skeptical, but after more tests Dr. Wolfram discovered active amoebae in Paul’s system. The cure was a set of shots followed by a regimen of pills, and a strict diet. Paul dreamed of rognons flambés, but was not allowed wine or alcohol, rich sauces, or cooked fats. It was an exquisite torture to be living in Paris, with a cook, and to be denied any tasteful food at all.

I, too, had had tummy troubles. Ever since our trip to Italy with Philapop, my stomach was no longer a brass-bound, iron-lined, eat-and-drink-any-amount-of-anything-anywhere-anytime machine that it had been. I had suffered bouts of feeling quite queer the entire time we’d been in France. “It must be something in the water,” I’d say to myself. But when I continued to feel suddenly sick and gaseous, I declared: “Aha, pregnant at last!”

We had tried. But for some reason our efforts didn’t take. It was sad, but we didn’t spend too much time thinking about it and never considered adoption. It was just one of those things. We were living very full lives. I was cooking all the time and making plans for a career in gastronomy. Paul—after all his years as a tutor and schoolteacher—said that he’d already spent enough time with adolescents to last him a lifetime. So it was.

A French doctor diagnosed my persistent nausea as nothing more than good old crise de foie—a liver attack, also known as “an American stomach in Paris.” Evidently, French cuisine was just too much for most American digestive systems. Looking back on the rich gorge of food and drink we’d been enjoying, I don’t find the diagnosis surprising. Lunch almost every day had consisted of something like sole meunière, ris de veau à la crème, and half a bottle of wine. Dinner might be escargots, rognons flambés, and another half-bottle of wine. Then there was a regular flow of apéritifs and cocktails and Cognacs. No wonder I felt ill! In a good restaurant, even a simple carrot-cream soup has had the carrots and onions fondus gently in butter for ten to fifteen minutes before being souped.

Alas, when I lightened my diet and got plenty of rest, my gaseous upset persisted. Upon hearing this, Dr. Wolfram said it was entirely possible that I, too, had picked up something in Asia during the war. He put me on an anti-dysentery treatment and restricted my diet. No fun!

PAUL AND THE American cultural attaché, Lee Brady, were organizing a number of exciting exhibits at the embassy, including shows of Grandma Moses paintings, dance photos from the Museum of Modern Art, and a collection of U.S. engravings and printing books. To mount these shows, he had to be a combination diplomat-hustler-bully, in order to navigate the wildly different styles of the French and American bureaucracies.

Paul with a visitor at one of his exhibits

The individualistic, artisanal quality of the French baffled the men Paul called the “Marshall Plan hustlers” from the U.S.A. When American experts began making “helpful” suggestions about how the French could “increase productivity and profits,” the average Frenchman would shrug, as if to say: “These notions of yours are all very fascinating, no doubt, but we have a nice little business here just as it is. Everybody makes a decent living. Nobody has ulcers. I have time to work on my monograph about Balzac, and my foreman enjoys his espaliered pear trees. I think, as a matter of fact, we do not wish to make these changes that you suggest.”

The Americans couldn’t even scare the French into changing their ancient ways. Why should they wreck a small but satisfying system that everybody liked, only to have the Communists take over? The French were personally patriotic, but too individualistic to create a new system to benefit the nation as a whole, and dubious about the cost of new machinery, the hurry-hurry-hurry, the instability of change, and so on.

This clash of cultures was quite amusing, and though Paul and I were temperamentally more sympathetic to the French than to the American approach, we were also its victims. Once, a French friend took us to a wonderful little café on the Right Bank—the kind of out-of-the-way place one needs a local guide to find—and introduced us to the proprietress. “I’ve brought you some new customers!” our friend proudly said. With hardly a glance in our direction, Madame waved a hand, saying, “Oh no, I have enough customers already. . . .” Such a response would be unimaginable in the U.S.A.

Near the end of 1950, Lee Brady was suddenly ordered to Saigon as public-affairs officer (PAO) in charge of USIS activities for Indochina—a most difficult and dangerous assignment indeed. He would be forced to work with the Bao Dai regime, which had not been freely chosen by the majority of citizens. Paul grew upset that the U.S.A. often found itself supporting weaklings and stooges—King George in Greece, Chiang Kai-shek in China, Tito in Yugoslavia, and now Bao Dai. What was an emissary of the U.S. government supposed to say when the Communists claimed, correctly, that his government supported a puppet, dictator, or horror?

VII. THE ARTISTES

IT WAS OCTOBER, and cold, but those wonderfully juicy and perfumed Parisian pears were in season, and despite our tender tummies we ate them for breakfast, along with bowls of cornflakes and Grape-Nuts. We would wash it all down with Chinese tea, which had a less poisonous effect on our plumbing than coffee.

Oh, it was so cold now. I hated it. The water hadn’t frozen in the gutters yet, although it was twenty-seven degrees and should have. It took real courage to leave our warm(ish) salon and venture into the frigorification of the house, where our breaths came out as steam. Every year at this time, I found myself thinking about our toasty little house in Washington, D.C.: push a button, and the entire place was warm in literally five minutes. But, I scolded myself, I’d had such a soft life—never known Hunger, never known true Fear, or been forced to live under the boot heel of an Enemy—that it was good for me to have an idea of what so many people in the world were going through.

On November 7, 1950, we celebrated our second anniversary in Paris. On a whim, Paul and I decided to indulge ourselves at one of our places, Restaurant des Artistes, up near Sacré-Coeur. At the Chambre des Députés we jumped on a metro to the Place Pigalle, and walked a couple of blocks toward the Montmartre hill. Along the way, we stopped to look at the pictures of naked girls in front of Les Naturistes. As we stood there gazing at a funny photo of a line of girls, back to the camera, holding their skirts up to show a row of bare buttocks, a young, fast-talking tout was giving us a non-ending pitch on the glories awaiting us within, uttered in about five languages—French, German, Italian, English, and a weird one which might have been Turkish. We laughed and kept moving along the avenue, crowded cheek-to-jowl with shooting galleries, strongman tests, and merry-go-rounds. We paused to shoot ten arrows with an all-metal bow, then, at Rue Lepic, we ducked into the restaurant.

The Artistes was a small, neat place with only ten tables (about forty seats) in its dining room. But stashed away in its cave were some fifty thousand bottles of exquisite wine. The dining room was warm and always filled with that wonderful smell of good cooking—a white-wine fish stock reducing, a delectable something being sautéed in the best butter, the refreshing sting of a salad tossed in a vinaigrette.