CHAPTER 5

French Recipes for American Cooks

I. SITUATION CONFUSED

IT WAS EARLY October 1954, and the sky was gray and the air chilly as we approached the German border. The thought of living in that land of monsters caused me to suffer le cafard (the blues). But cross we did, with me trembling like a leaf. We drove straight into Bonn and had lunch at a small restaurant. Having taken eight language lessons before leaving Washington, I could say, “Hello, how are you? My name is Child. How much does that cost? I want meat and potatoes. I am learning German.” I used all of these phrases immediately when we ordered beer, meat, and potatoes. The waitress understood me perfectly and smiled nicely as she placed two enormous foaming steins in front of us. My, that beer tasted good.

In the afternoon we made our way to Plittersdorf, in the suburbs of Bad Godesberg, to our new home at 3 Steubenring. Our hearts sank at the sight of it. I felt that if we were going to be in Germany then we should live amongst the Germans. But this wasn’t German at all. We could have been in Anytown, U.S.A.: there was a movie theater, a department store, a colonial church, and a set of modern beige three-story concrete apartment buildings with red trim, brown tile roofs, and radio antennas. Hmm.

We were shown nine apartments, every one of which was small, charmless, and dark. We chose Number 5, the one with the lightest-colored furniture. The kitchen was adequate, but came with an electric stove, which I didn’t like because it was difficult to control the heat. Worst of all, when you walked in our front door, you looked right into the bathroom. Still, we were right near the Rhine River, which was full of barges and looked like the Seine if you squinted. Across the way was a pretty green hill with some kind of Wagnerian ruins perched near the top.

Oh, how I missed our Marseille balconies, with their sweeping views and blazing sunlight!

I wished we lived in Munich or Berlin, somewhere where there was a bit of civilization, rather than sad old Plittersdorf on the Rhine. I found German to be a difficult and bristly language. But I was determined to learn how to communicate so that I could do some proper marketing—an activity I enjoyed no matter where I was. I began by taking language classes from the U.S. Army; Paul wanted to join me, but was immediately swept into work, and had no time for it.

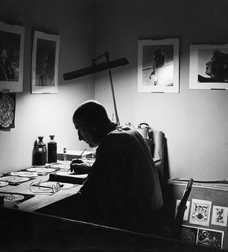

HIS TITLE WAS exhibits officer for all of Germany, which meant he was America’s top visual-program man for the entire country. His job was to inform the German people about the U.S.A., and once again he was organizing exhibits, tours, and cross-cultural exchanges. Because of the geopolitical/propaganda importance of Germany, which was right smack up against the Iron Curtain, his department had a budget of ten million dollars a year, more than the combined budgets for all of the USIA’s other information programs around the world. It was a big job, a huge professional step up, and I was proud of him.

Paul’s office was in a vast structure, seven stories high, and almost half the bulk of the Pentagon. He had a large and very able staff, and since we were living and working in an almost entirely American enclave, they were the only Germans we really got to know. As he was wont to do, Paul treated his staff as individuals rather than as underlings to be bossed around. “They seem more aware of my worth than the Americans do,” he noted.

Morale was not great. Paul’s boss was a selfish, immature fellow we called Woodenhead, and his assistant was known as Woodenhead the Second. Foreign Service and army types never got along especially well, and the divide was especially noticeable in Plittersdorf. The army families showed almost no interest in Germany or the Germans, which I found depressing. Hardly any of them spoke the language, even after having lived there for several years. The wives were perfectly nice, but conventional, incurious, and conservative; the men spoke in Southern accents, usually about sex and drink.

They drank beer, but only the lighter, American-style beers. What a shame! They were surrounded by some of the most wonderful beers in the world—and, with a 13.5 percent alcohol content, some of the strongest, too—but they deemed the traditional German ales “too heavy.” We quite liked German beers. Our favorite was a flavorful local beer called Nüremberger Lederbrau.

On the weekends, Paul and I would drive into Bonn to do our shopping, each with a pocket dictionary in hand. We bought chickens, beans, apples, lightbulbs, an extension cord, olive oil, vinegar, and a rubber stamp that said “Greetings from Old Downtown Plittersdorf on the Rhine.” I have always been a nut for rubber stamps, and I couldn’t wait to use this one on our letters. Stamp, stamp, stamp! At lunch, we took half an hour to decipher the menu, then ordered smoked sausage, sauerkraut, and beer. It was delicious, and, again, we were struck by how nice the Germans were. I struggled to reconcile the images of Hitler and the concentration camps with these friendly citizens. Could they really be the same people who had allowed Hitler to terrorize the world just a few years earlier?

As my German improved, I began to explore my new surroundings.

The local stores were good for meats. Aside from the usual sausages and chops and steaks, you’d see quite a bit of venison and game for sale. You could buy a hare all cut up and sitting in a tub of hare’s blood, which was perfect for making civet de lièvre. Krämers was the swish market in Bad Godesberg, and it was there that I picked out a fresh young turkey to roast. By gum if the whole back of the store wasn’t turned over to row upon row of fat geese, ducks, turkeys, roasting chickens, and pheasants. They were arranged in neat tiers, each fowl marked with the customer’s name. It was a really beautiful sight.

But, to my palate, German cooking didn’t hold a match to the French. The Germans didn’t hang their meats long enough to develop that light gamy taste I adored, and they didn’t marinate. But I discovered that if you bought the meat, hung it, and marinated it yourself, you could make as pretty a dish as you could hope to find.

Soon I was back to woodpeckering on The Book, which we were now calling French Cooking for the American Kitchen. Simca and I had finished the chapters on soups and sauces, and we thought the chapters on eggs and fish were nearly done. While I began to focus on poultry, Simca began to work on meats.

She was a terrifically inventive cook. Wildly energetic, Simca was always tinkering with something in the kitchen at 6:30 a.m. or tapping on her typewriter until midnight. Her intensity bothered Paul (“Living with her would send me screaming into the woods,” he declared), but was a wonderful asset to me. We agreed that she would be the expert on all things French—spellings, ingredients, attitudes, etc.—while I would be the expert on the U.S.A. Together, we worked like a couple of vaches enragées!

Although I resented the distance between us at first, I came to believe that it was a blessing in disguise. It allowed us to work on things independently without getting in each other’s hair. We conferred constantly by mail, and visited each other on a regular basis.

Both willful and stubborn, we had by now grown used to each other’s idiosyncrasies: I liked finely ground salt, whereas she preferred the coarser style; I liked white pepper, she preferred black; she loathed turnips, but I loved them; she favored tomato sauce on meats, and I did not. But none of these personal preferences made any difference at all, because we were both so enthusiastic about food.

In January 1955, I began to experiment with chicken cookery. It was a subject that encompassed almost all the fundamentals of French cuisine, some of its best sauces, and a few of its true glories. Larousse Gastronomique listed over two hundred different chicken recipes, and I tried most of them, along with many others we had collected along the way. But my favorite remained the basic roast chicken. What a deceptively simple dish. I had come to believe that one can judge the quality of a cook by his or her roast chicken. Above all, it should taste like chicken: it should be so good that even a perfectly simple, buttery roast should be a delight.

The German birds didn’t taste as good as their French cousins, nor did the frozen Dutch chickens we bought in the local supermarkets. The American poultry industry had made it possible to grow a fine-looking fryer in record time and sell it at a reasonable price, but no one mentioned that the result usually tasted like the stuffing inside of a teddy bear.

Simca and I spent a great deal of time analyzing the different types of American chickens versus French chickens, and what the most suitable method of preparing each would be—roasted, poached, sautéed, fricasseed, grilled, in casseroles, coq au vin, à la diabolique, and poulet farci au gros sel, and so on and on. We had to choose with great care which of these recipes to use in our book. Not only should a dish be of the traditional cuisine française, but it should also be composed of ingredients available to the average American cook. And, as always, it was important to develop a theme and several variations. For sautéed chicken, then, we wanted to include a crisp, a fricasseed, and a simmered version, yet we didn’t want to do an entire book’s worth of chicken dishes.

Even though Simca and I were both putting in forty hours a week on The Book, it went very slowly. Each recipe took so long, so long, so long to research, test, and write that I could see no end in sight. Nor could I see any other method of working. Ach!

Louisette, alas, wasn’t contributing very much. She had a difficult husband, two children, and a household to run; the most she could offer was three hours a week teaching at L’École des Trois Gourmandes (which Simca continued to run) and six hours a week for book research. I was sympathetic, but our intense effort on a serious, lengthy magnum opus did not really fit Louisette’s style. She would have been better suited to a quick book on chic little dishes for parties. The hard truth, which I dared not voice to anyone other than Paul and Simca, was that Louisette was simply not a good enough cook to present herself as an equal author. This fact stuck in my craw.

We had at least another year’s worth of work ahead of us, and I felt it important that we formally acknowledge who was actually doing what. It was too late to change the wording on the Houghton Mifflin contract, our lawyer said, but we all agreed that henceforth Simca and I would legally be known as “Co-Authors” and Louisette would be called a “Consultant.” We agreed to work out the financial details when, or if, the book was published. This was a difficult subject to discuss, but I was relieved to see our responsibilities clearly laid out on paper.

In matters of business, I felt we had to be as clearheaded and professional as possible, even at the risk of offending our friend. When Simca wavered a bit, I wrote: “We must be cold-blooded.”

ONE THURSDAY IN April 1955, Paul received orders to return to Washington, D.C., by the following Monday. No reason was given, but we suspected that someone at headquarters had finally woken up and realized it was time to give my husband a promotion. Would he be made head of the department? Would he finally get a raise? Would we be recalled to the States for important work in Washington? Off he flew, to find out.

I was about to leave for a trip to Paris, but as I was packing I received a telegram from Paul in Washington: “Situation confused.”

No one could, or would, tell him why he was there. He had been made to sit and wait in anonymous offices for various VIPs who were MIA. He suggested that I delay my Paris visit, which I did.

“Situation here like Kafka story,” he telegrammed.

By Wednesday, the bizarre truth had dawned on me: Paul wasn’t being promoted, he was being investigated. For what? By whom? Would he be arrested?

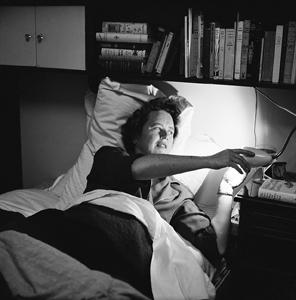

I couldn’t reach him, and began frantically calling our extensive network of friends in the Foreign Service to find out what was happening. I stayed up until four o’clock in the morning talking on the phone. What I eventually pieced together was that Paul had spent all day and into the evening being interrogated by agents from the USIA’s Office of Security, an outfit run by one R. W. McLeod, who was said to be a J. Edgar Hoover protégé.

When they finally appeared, the investigators had a fat dossier on Paul Cushing Child. They attacked him with questions about his patriotism, his liberal friends, the books he read, and his association with Communists. When they asked if he was a homosexual, Paul laughed. When they asked him to “drop his pants,” he refused on principle. He had nothing to hide, and said so. The investigators eventually gave up on him.

But, clearly, someone had implicated Paul as a treasonous homosexual. Who would do such a thing, and why? The whole episode was shockingly weird, amateurish, and unfair. Paul felt he had acquitted himself well under the circumstances, and had proved himself “a monument of innocence.” Later, at his insistence, the USIA gave him a written exoneration. Still, this shameful episode left the taste of ashes in our mouths, and we would never forget it.

What was happening to America? Several of our friends and colleagues were tormented by McCarthy’s terrible witch-hunt. It ruined careers, and in some cases lives. Even President Eisenhower seemed unwilling to stand up to him, which made me angry. When Eisenhower announced that he’d run for a second term, after having a heart attack, I had no doubt that Adlai Stevenson would make the better (and more resilient) president. Ike was just not inspiring: I got nothing but a hollow feeling from his utterances, as if Pluto the dog were suddenly making human noises. Just about anyone from the GOP had, for me, a fake soap-selling ring to him, with the exception of Herbert Hoover, who had impressed everyone on a recent swing through Europe. Stevenson, on the other hand, had a nobility of ideals that appealed to me. I just liked eggheads, damnit!

While Paul was in the States, he decided to zip up to New York, where he met with Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art, to arrange to bring the photographer’s wonderful “Family of Man” exhibit to Berlin. He had befriended Steichen while we were stationed in Paris, and Steichen had bought six of Paul’s photos for the MoMA collection. That was a real coup, but one that modest Paul played down.

I, in the meantime, had finally packed myself off to Paris for three weeks. I cooked with Bugnard, taught classes with Les Trois Gourmandes, ate with the Baltrus, and immersed myself in cookery-bookery with Simca. What a tonic!

OVER THE SUMMER and into the fall of 1955, I finished my chicken research and began madly fussing about with geese and duck. One weekend I overdid it a bit, when, in a fit of experimental zeal, I consumed most of two boned stuffed ducks (one hot and braised, one cold en croûte) in a sitting. I was a pig, frankly, and bilious for days, which served me right. I was also running a continual set of experiments on risotto (finding just the right water-to-rice ratio), how to make stocks in the pressure cooker (determining proper timing, testing poultry carcasses versus beef bones), and various desserts. This sort of research was a challenge to our ongoing Battle of the Belly.

“No man shall lose weight who eats paella topped with Apfel Strudel,” Paul noted, after doing exactly that.

We had been horrified to notice that baby blubber seemed to bounce on so many people in the States. In Germany, meanwhile, a large figure denoted social status. Our goal was to eat well, but sensibly, as the French did. This meant keeping our helpings small, eating a great variety of foods, and avoiding snacks. But the best diet tip of all was Paul’s fully patented Belly Control System: “Just don’t eat so damn much!”

At Christmastime, Paul was felled by a nasty infectious hepatitis. After a recuperative stay in Rome in the early days of 1956 (where I discovered fennel salad and the toothsome little Roman peas), we had decided to eat carefully, exercise rigorously, and eschew alcohol. As a result, he had dropped ten pounds and tipped the scales at 173. I had lost eleven pounds and weighed 158, which made me feel less middle-aged than I had in the U.S.A.

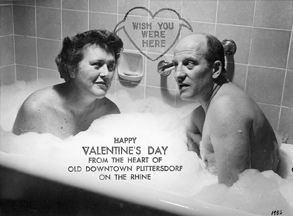

Come February, all of our off time was spent composing letters for the hundreds of valentines we sent out around the globe. Valentine cards had become a tradition of ours, born of the fact that we could never get ourselves organized in time to send out Christmas cards. With our ever-enlarging network of family, friends, and Foreign Service colleagues, we found that Paul’s hand-designed valentine cards—usually a woodcut or drawing, sometimes a photograph—were a nice way to keep in touch. But they could be labor-intensive. One year’s design was a faux stained-glass window, with five colors in it, each of which had to be hand-painted in watercolors—which took hours. For 1956, we decided to lighten up by doing something different: we posed ourselves for a self-timed valentine photo in the bathtub, wearing nothing but artfully placed soap bubbles.

BY THE SPRING OF 1956, we decided it was high time to start entertaining again. But our first dinner party revealed that our once-crack team of hostess/cook and host/sommelier was woefully out of practice. We had no salad forks, we forgot to clear the cocktail clutter unobtrusively, and we spent the evening rushing about in a breathless rush. This was not up to our usual standard. We liked to treat our guests as if they were royalty, so as to be fully prepared for those occasions when we would be called upon to entertain actual royalty!

For our second dinner party, I served les barquettes de champignons glacées au fromage, canard à l’orange, and glace maison aux marrons glacés. A week later, I tried boeuf à la mode, endives braisées, and a dessert of désirés du roi for friends. And now the old “Pulia” entertainment engine was humming along beautifully.

I got a note from le prince, Curnonsky, who had broken several ribs in a fall. The doctors, he wrote, had put him on “un régime terrible” that did not allow for cream, salt, sauces, or wine. Such a bland diet must have been a torture for the old gastronome.

Health was much on our minds that season. Over the Easter weekend, I had to go into a private Klinik in Bad Godesberg for an operation. Two years earlier, I had undergone surgery in Washington to remove uterine polyps, but it had not, apparently, gotten to the root of the matter. “I feel just fine,” I said, but the German doctor insisted that an operation was best for me. His Klinik was in a grand Victorian mansion painted all white. The surgery was routine. I was not concerned, but poor Paul half convinced himself that “polyps” equaled “Julia is dying of cancer.” This was not true, of course, and he knew it, yet he was so worried he hardly slept a wink and even developed a slight fever that night.

Paul thought about death much more than I ever did. In part, this must have come from the early demise of his father, his mother, and his older sister. Paul had also been traumatized by the death of Edith “Slingsby” Kennedy, his serious girlfriend before the war. She was a sophisticated older woman, and they had lived together (unmarried!) in Paris and in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She had died of cancer just before the war, and he remained haunted by her death. Also, our friends were aging now, and some, like Bernard De Voto (whom we didn’t know very well), had recently died.

After Benny’s death, Avis De Voto, who had two sons to care for, had spent months rearranging her life. Once things had settled, she took a recuperative vacation to Europe in the spring of 1956. Luckily, we had arranged a vacation at just the same time, so we met up with her in London. We had a fine time there, walking and shopping and socializing.

Avis was small, dark-haired, and full of opinions. The better we got to know her the more we liked her. One night she introduced us to a six-foot-seven-inch-tall moose of a Harvard economist named John Kenneth Galbraith. We had quite a lot in common with him, and as we all sat in a loud basement restaurant, we compared notes on time spent in India, art, and global politics. It clearly did Avis good to be out amongst lively friends. And after the dolors of Plittersdorf, it did us good, too.

Avis, Paul, and I crossed the Channel on a beautiful day and met up with Simca and Jean Fischbacher in Rouen, where the war-damaged cathedral was finally being repaired. Ever energetic, Simca had phoned ahead to arrange a special lunch for us at the Hôtel de Dieppe, where the chef, Michel Guéret, specialized in canard à la rouennaise, a celebrated pressed-duck dish seldom used anymore. What an experience!

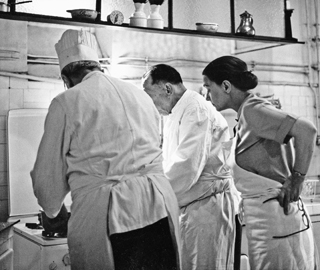

Avis De Voto with Chefs Bugnard and Thilmont

We began with trout stuffed with minnows and a wonder-sauce made of herbs, white wine, and butter. Then on to the famous, ritualized canard. The duck itself is a special strain bred from a domestic female “covered” by a wild male, which produces handsome dark-feathered birds that are full-breasted and toothsome. They are killed by being smothered, so as to keep the blood inside the body (an example of the lengths the French will go to for a special meal). Chef Guéret roasted two of these ducks on a spit for us, all the while basting them with a wonderful duck-blood sauce he’d prepared at a side table. The birds became mouth-wateringly brown on the outside and roasted very rare on the inside. When they were done, he deftly carved off the ducks’ legs and wings, rolled them in mustard and crumbs, and sent them back to the kitchen to be grilled.

He very carefully peeled the skin away from the breast, and carved the meat into thin slices, which he sprinkled with finely minced shallots. These would be poached in their juices, a little wine, and delicate seasoning, in order to point up the natural flavor. Next the chef wheeled a great silver duck press up to our table. It looked a bit like a silver fire extinguisher with a round crank-handle on top. He cut up the carcass, put it into the canister of the press, and turned the big handle on top. As the pressing plate descended slowly inside the canister, we could hear the cracking of bones, and a stream of red juices dribbled out of the spout into a saucepan. Adding a dollop of red Burgundy wine to the press, the chef turned the crank again, to squeeze some more. He continued like this until the carcass had finally rendered its all. It was a fabulous ritual to watch, and we marveled over Guéret’s every move with rapt attention.

Finally, it was time to eat. We began with the tender slices of breast slathered in sauce, and then the nicely crisped and crumbly grilled legs and wings. We washed these delicacies down with a splendid Pommerol. Then we had an assortment of cheeses, glasses of very old apple brandy, and cups of coffee. It was a tour de force.

Normandy was filled with apple blossoms, flowering chestnut trees, and the warm earthy smells of early spring. We drove slowly toward Paris, savoring the landscape, exploring the ruins of a Cistercian monastery, and wandering around old villages where the houses had thatched roofs.

Paris was gorgeous and packed with people. We took Avis for a drink at the Deux Magots, and dined in tremendous style at L’Escargot, where we were surrounded by rich Americans in blue mink and ended our meal with perfectly ripe strawberries and champagne. From there we wandered over to Notre Dame, now illuminated at night by big banks of searchlights, making for a rather dramatic effect. Finally, we ended up at Le Caveau des Oubliettes Rouges, where we sang old French folk songs until one o’clock in the morning. We left with a feeling of pure happiness.

After packing Paul off on the train to Germany, Avis and I dropped by Mère Michel’s to see if her famous beurre blanc had withstood the test of time. The answer: yes, though it tasted no better than ours.

While I reconnected with Bugnard, the Baltrus, and the Asches, Avis spent a wonderful day in La Forêt de Rambouillet with Simca and Jean Fischbacher, returning to the hotel that night with a great armload of lilies-of-the-valley and a beaming face.

Germany was a frigid, wet fifty-two degrees when I returned. Paul and I had to don our English tweeds to keep warm. We looked at each other and sighed. After the glories of la belle France, where all of our impressions were heightened and magnified by the companionship of our friends, it was hard to avoid the conclusion that Plittersdorf was a miserable dump.

IN JULY 1956, we read in the Paris Herald that dear old Curnonsky had died. The prince élu des gastronomes had fallen off his balcony to his death. Was it an accident, or suicide?

I had seen him in Paris, briefly. He had not looked well, and complained bitterly about the strict diet his doctors had prescribed. At one point he muttered, “If only I had the courage to slit my wrists.” What a tragic and bitter end. One couldn’t help feeling that he was happier now than in his final days, and that his passing marked the end of an era.

BY THE TIME my forty-fourth birthday rolled around in August, Paul was immersed in an enormous show in Berlin called “Space Unlimited,” about the U.S. space program. It drew capacity crowds and was deemed a “phenomenal success.” For weeks I hardly saw my husband, and found myself to be an unhappy “widow.” Well, I reminded myself, Avis is a real widow, so imagine how she must feel.

Paul’s success with “Space Unlimited” had been noted in the halls of power, and by the fall of 1956 “they” had decided they needed Mr. P. Child back in Washington, D.C. The main USIA exhibits department there had become a shambles, and he was the man to fix it. So we’d be moving back to the States again, which came as welcome news. I was itching to say auf Wiedersehen to Woodenhead (who had given Paul poor marks for administration) and the Plittersdorf way of life.

Once again we were packing up and preparing to move on, like nomads. And, once again, we felt the tingle of excited apprehension about returning to our native soil—now the land of “Elvis the Pelvis,” Nixon-lovers, and other strange phenomena. But this time, something was bothering us: ever since Paul had been investigated, we had grown slowly but surely more disenchanted with working for the U.S. government. Paul felt he was doing important work but was not being recognized for it, and I was getting good and sick of uprooting our lives every few years.

“Maybe,” we confided to each other, “there is more to life than this.” But what else might we do? And where might we do it?

II. THE DREAM

WE ARRIVED BACK in Washington, D.C., in November 1956, and almost immediately dove into the task of renovating our little jewel of a house at 2706 Olive Avenue. It was a 150-year-old, three-story wooden house, on the outskirts of Georgetown. We’d bought it in 1948. Over the last eight years, we had rented it out, and now it was showing the wear and tear. Luckily, we had banked enough rent money to spiff up an office/guest bedroom for me and a studio for Paul on the top floor, rework the wiring, plug a ceiling leak, and expand the kitchen. What fun to feather our own little nest, the only nest we actually owned.

Using a small inheritance from my mother, I bought a new dishwasher and a sink equipped with an “electric pig,” a waste-disposal grinder. (No maids for me!) Then I decided I needed a new stove. One day we were visiting a gourmand friend, Sherman Kent, whom we called Old Buffalo; with a ceremonial sweep of the hand, he showed me the stove in his kitchen. It was a professional gas range, and as soon as I laid eyes on it I knew I must have one. In fact, Old Buffalo sold me his. It was a low, wide, squat black number with with six burners on the left and a little flat-steel griddle on the right. I paid him something like $412 for the stove, and I loved it so much I vowed to take it to my grave!

Paul, meanwhile, had finally been promoted from FSS-4 (Foreign Service rank four) to FSS-3. He now earned a whopping $9,660 a year doing exhibition work.

Our neighborhood was technically in the city but had a nice small-town feel, because everyone marketed at the same place, or met at the post office or in the barbershop. Though I would have preferred to live in Paris while working on French Cooking for the American Kitchen, one huge advantage to living in the States was that I could do on-the-ground research about what kinds of produce and equipment were available to our audience.

“It is great fun being back here to live. I never could get the feel of it when we just passed through,” I reported to Simca. “One thing I do adore is to be shopping in these great serve-yourself markets, where . . . you pick up a wire push cart as you come in and just trundle about looking and fingering everything. . . . It is fine to be able to pick out each separate mushroom yourself. . . . Seems to me there is everything here that is necessary to allow a good French cook to operate.”

But American supermarkets were also full of products labeled “gourmet” that were not: instant cake mixes, TV dinners, frozen vegetables, canned mushrooms, fish sticks, Jell-O salads, marshmallows, spray-can whipped cream, and other horrible glop. This gave me pause. Would there be a place in the U.S.A. for a book like ours? Were we hopelessly out of step with the times?

I decided to ignore my doubts and push on. There wasn’t much else I could do. Besides, I loved la cuisine bourgeoise, and perhaps a few others would, too.

Simca, meanwhile, was suffering from la tension (high blood pressure and jumpy nerves). This was a sensitive subject for me, as my mother had died young of high blood pressure. “You must pay attention to your health,” I cautioned her. Simca didn’t take criticism well, so I tried to illustrate my point by telling her about Paul’s twin, Charlie Child: “Everything he does is at full speed, like a rocket taking off,” I wrote. He lived each moment “as if it were the supreme one, requiring every ounce of energy. You are the same. You have to let a few things . . . slip by you, rather than being pitched at the highest key. . . . Force yourself to relax at times. It is not necessary to do everything as though your life and honour depended on it.” I doubt my words had any effect on her.

IN THE SPRING OF 1957, I began to teach cooking classes to a group of Washington women who met on Monday mornings to cook lunch for their husbands. Later that year, I commuted once a month to Philadelphia, to teach a similar class to eight students there. A typical menu would include oeufs pochés duxelles, sauce béarnaise; poulet sauté portugaise; épinards au jus, and pommes à la sévillane.

I was now an experienced teacher. The night before each class, I would type up the menu and list of ingredients. (Usually I’d forward copies of these menus to Simca, who was teaching a group of U.S. Air Force wives in Paris.) Teaching gave me great satisfaction, and soon my days fell into a comfortingly regular rhythm.

Most of my time was spent revising and retyping our now dog-eared, note-filled, butter-and-food-stained manuscript. In retesting certain dishes in my American kitchen-laboratory, I discovered that hardly anyone used fresh herbs here, that U.S. veal was not as tender as the French, that our turkeys were much larger than their birds, and that Americans ate far more broccoli than the French did. This on-the-ground reporting would be crucial to the success of our book, I knew, but it could also be exasperating.

“WHY DID WE EVER DECIDE TO DO THIS ANYWAY?” I wailed to Simca, after discovering that my beloved crème fraîche was nearly impossible to find in America.

IN JANUARY 1958, Simca and Jean made their first visit to the United States. Jean could only stay a short while, but Simca stayed for three months. She hadn’t slowed down one bit, and rushed about visiting friends and former students in New York, Detroit, Philadelphia, and California. In Washington, she and I went on shopping/research expeditions and gave a few lively classes together in our Olive Avenue kitchen, where we demonstrated dishes such as quiche aux fruits de mer, coq au vin, and tarte aux pommes. She was thrilled by America, and sampled our food and drink with vast enthusiasm, including drugstore tuna fish, frozen blinis, and—her favorite—bourbon!

We had a fine time together, but our manuscript remained far from finished. We had promised to show the Houghton Mifflin editors what we’d written so far, but we were a little nervous, because it was seven hundred detailed pages on nothing but poultry and soups. Added to that, our recipes did not appeal to the TV-dinner-and-cake-mix set. We had discovered this fact, with a bit of a shock, when we attempted to place our work in a few of the mass-circulation magazines. Not one of them was interested in anything we’d done. The editors seemed to consider the French preoccupation with detail a waste of time, if not a form of insanity.

Yet I had run into many Americans who had gone to France and been inspired by the wonderful taste of the food there—“Oh, that juicy roast chicken!” they’d exclaim. “My, that sole normande!” Though some returned to the U.S. convinced that such wonders could only be achieved by the magic of being born French, the savvier ones realized that the main ingredient in such succulent dishes was hard work coupled with proper technique.

Unfortunately, this was not a message that the food editors of America wanted to hear or had the technical knowledge to appreciate.

Most of our pupils had traveled and cooked for years, but did not know how to sauté, or cut a vegetable quickly, and had no conception of how to treat an egg yolk properly. I knew—because they told me so—that they wanted this information and were willing to work for it. So I was convinced there would be a market for our work. Would Houghton Mifflin agree?

In the days leading up to our meeting, I rehearsed the arguments I would make in Boston in my correspondence with John Leggett, the publisher’s New York editor. He was concerned about the scope and detail of French Cooking for the American Kitchen. “Good French food cannot be produced by a zombie cook,” I wrote him. To get the proper results, one had to be willing to sweat over it; the preliminaries must be performed correctly and every detail must be observed. “Ours is the only book either in English or in French which gives such complete instructions,” I explained. It “constitutes a modern primer of classical French cooking—an up-to-date Escoffier, if you will, for the American amateur of the ‘be your own French chef’ persuasion.”

On February 23, the day before our appointment at Houghton Mifflin, it was snowing so hard that all of the trains to Boston were canceled. Simca and I looked at each other. After we had put so many years of hard work into French Cooking for the American Kitchen, would a mere blizzard stop us? Non! We were determined to deliver what we’d promised.

Late that morning, we boarded a bus. It chugged and slithered northward through the driving snow for hour upon hour, while one or the other of us clutched a cardboard box holding our precious manuscript in our laps. At about 1:00 a.m., we finally straggled into Avis De Voto’s house, on Berkeley Street, in Cambridge.

The next day, it was still snowing. Simca and I made our way to 2 Park Street, in Boston, where we mounted a long flight of stairs. Cradling our precious box under my arm, I had no idea how our efforts would be received. In the editorial offices, we finally met Dorothy de Santillana, a nice, straightforward woman who understood cooking and seemed genuinely enthusiastic about French Cooking for the American Kitchen. But we did not get a very warm feeling from her male colleagues. One of them muttered something like “Americans don’t want an encyclopedia, they want to cook something quick, with a mix.”

Simca and I left our seven hundred authoritative pages on soups and poultry with them, slowly descended the long flight of stairs, and returned to Avis’s through the snow. Neither of us said much.

A few weeks later, we received a letter from Dorothy de Santillana:

Our most careful group eye has been brought to bear on the fruit of what is self-evidently the most careful labor of love . . . and the problem presented is complex. . . . With the greatest respect for what you have done . . . we must state forthwith that this is not the book we contracted for, which was to be a single volume book which would tell the American housewife how to cook in French.

From here we must talk publishing, not cooking. . . . What we could envisage as saleable . . . is perhaps a series of small books devoted to particular portions of the meal. Such a series would have a logical sequence of presentation . . . such as soups, sauces, eggs, entrees, etc. . . . Such a series should meet a rigorous standard of simplicity and compactness, certainly less elaborate than your present volumes, which, although we are sure they are foolproof, are undeniably demanding in the time and focus of the cook, who is so apt to be mother, nurse, chauffeur, and cleaner as well.

I know this reaction will be a disappointment to you, but I wonder if this isn’t the time for you to do some re-thinking yourself on the project which has . . . grown into something much more complex and difficult to handle than the original book.

Ah me, our poor Gargantua. What would become of it?

It was true that we had not delivered the book Houghton Mifflin had contracted for. It was also true that the trend in the U.S.A. was toward speed and the elimination of work, neither of which we had furthered in our seven-hundred-page treatise. And it was true that the publisher’s suggestion of a simplified series of booklets aimed at the housewife/chauffeur would appeal to a wide audience. Yet the book Houghton Mifflin envisioned was not the book Simca and I were interested in. We felt that the mass audience was already abundantly served by women’s magazines and most cookbooks. We were far more interested in readers who were devoted to serious, creative cookery. We knew this was an audience that needed and wanted attention. It would, however, be a relatively small audience. Furthermore, the publishing business was in a period of doldrums.

What to do?

Simca and I agreed that, though we would be willing to prune our manuscript a reasonable amount, our objective remained firm: to present the fundamentals of classical French cooking in sufficient detail that any loving amateur could produce a perfect French meal. Houghton Mifflin was clearly not interested in this. And it was possible—maybe likely—that no other publisher would take a flyer on this kind of book, either. But before relinquishing our dream, we wanted to peddle the idea around.

With Simca standing over my shoulder, I typed a letter to Mrs. de Santillana, suggesting we return Houghton Mifflin’s $250, the first third of the advance, and cancel our contract for French Cooking for the American Kitchen. “It is too bad that our association must come officially to a close,” I wrote. “But we still have a good 30 or 40 more years of cook bookery in us, so we may sometime be able to get together again.”

Ouf! I went to bed that night feeling empty.

The next day, I crumpled the letter up. Inserting a fresh page into the typewriter, I wrote in a new vein: “We have decided to shelve our own dream for the time being and propose to prepare you a short and snappy book directed to the somewhat sophisticated housewife/chauffeur.”

It had been an extremely difficult decision. But Simca and I had finally conceded that it made more sense to compress our “encyclopedia” into a single volume, about 350 pages long, of authentic French recipes—from hors d’oeuvres to desserts—than to hunt for a new publisher right now. “Everything would be of the simpler sort, but nothing humdrum,” I wrote. “The recipes would look short, and emphasis would always be on how to prepare ahead, and how to reheat. We might even manage to insert a note of gaiety and a certain quiet chic, which would be a pleasant change.” As we had already tested our recipes, I promised to have the new manuscript finished within six months, or less.

Mrs. de Santillana wrote back, approving our new plan.

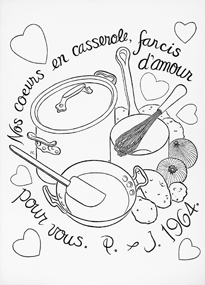

We knew we’d have to emphasize the simpler cuisine bourgeoise dishes over the grande cuisine. After all, our readers wouldn’t have mortars and pestles for pounding lobster shells, or copper bowls for whipping egg whites, and they weren’t used to taking the time and care over sauces that the French were accustomed to. Perhaps that would come with time. For now, I could see clearly that our challenge was to bridge the cultural divide between France and America. The best way to do that would be to emphasize the basic rules of cooking, and impart the things I’d learned from Bugnard and the other teacher-chefs—not least of which was the importance of including fun and love in the preparation of a meal!

III. OSLONIANS

PAUL HAD DECIDED to retire from government service when he turned sixty, in 1962, in order to devote himself to painting and photography. The next question was: what—and where—would we retire to? We didn’t love Washington enough to want to stay there, and we felt that California was too far away from our closest family and friends. We debated the subject back and forth, and after several visits to Avis De Voto in Cambridge, Massachusetts, we said to each other: “Now, there’s a place we can agree on.”

Paul had grown up in and around Boston and taught at the Shady Hill School in the 1930s, and felt comfortable there. I found Cambridge to have a special, charming New England character and to be full of interesting eggheads. Over the Fourth of July weekend, 1958, a real-estate agent friend of Avis’s walked us about the narrow, winding streets behind the Harvard and Radcliffe campuses. We didn’t see anything that appealed, but as we left, Avis said she’d keep an eye out for us.

Back in Washington, Paul had been given the title “acting chief of the exhibits division,” which meant he was the USIA’s top exhibits man. It was a temporary post that he held for about six months in 1958. In the meantime, we began to study Norwegian in preparation for our next posting. We were being sent to Oslo, where Paul would become the U.S. cultural attaché, starting in 1959.

While in Washington, I had met John Valentine Schaffner, a New York literary agent who represented James Beard and Mrs. Brown of “the Browns,” among others. I asked him about how Simca and I should make ourselves known to our vast potential public. He implied that the professional cooking world (both in the U.S. and in France) was a closed syndicate that was difficult to penetrate. So it may have been, but it was our intention to break into this group on a permanent basis. Clearly, we’d be in a better position to do so once we had a finished cookbook in hand. Simca and I bore down, working our stoves and typewriters to a white-hot heat.

In January 1959, as we were preparing to shove off for Norway, Avis called to say that a “special” house in Cambridge was coming on the market, and that we should drop everything and come right away to see it. It was a day of freezing rain, but we jumped on the train to Boston and had a look at the big, gray-shingled house she had described. It had been built in 1889 by the philosopher Josiah Royce (a native Californian, like me), and stood at 103 Irving Street, a small leafy byway tucked behind Harvard Yard. The house was three stories tall, with a long kitchen and a double pantry, a full basement, and a garden. We walked through it for about twenty minutes, and as Paul tapped the walls and floors to judge their soundness, I stood in the kitchen and imagined myself living there. Another family was touring the house at the same time. While they talked it over in low voices, we decided that we’d never find anything better and bought it on the spot. We paid something like forty-eight thousand dollars for it. It needed updating and improving, but we’d be able to pay for that by renting it out while we were in Norway. Hooray!

AS OUR FERRYBOAT from Denmark made its way up the winding Oslo Fjord in May 1959, we looked at the granite boulders and high cliffs covered with pine trees, sniffed the cool, salty-piney air, and said to each other: “Norway is just like Maine!” Which it was, and wasn’t.

You can prepare yourself to enter a new culture, but the reality always takes some getting used to. At that latitude, at that time of year, the surprisingly bright sun didn’t set until 10:20 p.m. and rose again almost immediately, at 4:00 a.m., which made sleep difficult. Furthermore, Norwegian beds are covered by a single down coverlet, which is as hot as a baker’s oven but only big enough to cover half of one’s body. We licked that problem by pulling it up to our chins and piling our car blanket and various bits of clothing onto our legs and feet.

There were hardly any pussycats about, I noticed, but plenty of dogs, and more redheads per square meter than anywhere else I’d ever been. Every Norwegian seemed to be good-looking and healthy, and to have an air of uncomplicated niceness.

The entire USIA staff in Oslo consisted of only three Americans and one Norwegian secretary. When a big shot like Buckminster Fuller came to town, Paul would have to put aside his usual pile of work to arrange lectures and press coverage and chauffeur the great man around. In the meantime, the U.S. Embassy was moving into a handsome new building designed by Eero Saarinen.

By June, we’d found a lovely house to rent in the suburbs, a two-story white clapboard, rather New Englandy–looking place, complete with a preposterous electric stove, an untuned piano, and ants. I hated ants, and set out to poison the little buggers. There were green hedges and fruit trees and climbing roses. The raspberries were ripening fast, and we had both the large strawberries and the little fraises des bois, which were highly perfumed and really good (better than the ones we’d had in France, which tasted woody).

I unpacked my vast batterie de cuisine—seventy-four items in total, from cheese graters to copper pots—arranged the kitchen to my liking, and began to take language classes. Soon my Norsk was good enough so that I could read the newspaper and go shopping. The fish and bread were excellent, as were the strawberries, raspberries, and gooseberries, but we were less impressed with the local meat—which included haunches of moose and reindeer—and the rather wan vegetables.

My favorite place to shop was a fish store with a stupendous window display: three-foot-long salmon crossed over each other, surrounded by salmon trout and interspersed with lobster, mackerel, flounder, and halibut. Above this was a garland of little pink shrimp. I would get to know this shop well, with its jolly fishermen standing around boxes of big crabs, great half-carved sturgeon, and live cod swimming in long tanks made of cement. One afternoon I stopped by when an Englishwoman was trying to take a definitive photograph of a cod. A fisherman obligingly pulled a giant specimen out of the tank, held it in his arms, scratched its belly, and cooed to it; the fish squeakily cooed back to him. What a fine act!

Aside from my French-cooking research for the book, I began to experiment with local produce. I picked red currants and made batches of jelly, tried gravlax for the first time (delicious served with a dill-cream sauce, and Steurder potatoes with cream and mace), and cooked a ptarmigan and a large European grouse called a capercailzie.

As I knew hardly a soul in Oslo, I got a great deal of work done on The Book that summer. Letters between Oslo and Paris flew back and forth at a great rate. After nearly eight years of hard labor, Simca and I could see the end in sight, and spurred each other on to heroic feats of typing.

IV. A GODSEND IN DISGUISE

SEPTEMBER 1, 1959, marked our thirteenth wedding anniversary, and I had just turned forty-seven years old. But the really exciting news was that the revised French Recipes for American Cooks was finished at last—ta-da!

I sent the manuscripple off to a friend in Washington for an immaculate typing up, and from there it would go to Houghton Mifflin in Boston. The book was now a wholly different beast from our original “encyclopedia” on soups and poultry. It was a primer on cuisine bourgeoise for serious American cooks, covering everything from crudités to desserts. But it was still 750 pages long, and I worried how the editors would react. We wouldn’t hear their comments for another month, and there was nothing we could do but cross our fingers and hope for the best.

What a strange feeling to be done with The Book. It had weighed so like a stone these many years, you’d think I’d be tripping about in ecstatic jubilation. But I felt rootless. Empty. Lost. I sunk into a slough of discombobulation.

Oh, how I yearned for a passel of blood-brother friends to celebrate with. We had plenty of acquaintances in Oslo, but, as in Plittersdorf, we suffered months and months of nobody to really hug but ourselves. This was the thing I hated most about the itinerant diplomatic life.

When I finally got myself invited to a large ladies’ lunch, we were served canned shredded chicken in a droopy, soupy sauce, and brownies from a mix. Yuck.

My mood buoyed when I received an enthusiastic note from Dorothy de Santillana at the end of September.

I have spent four full days studying the manuscript . . . which is a very long time for any single editorial reading. . . . I was intensely occupied every minute and remain truly bowled over at the intensity and detail with which you have analysed, broken down, and reconstructed every process in full minutiae. I surely do not know any compendium so amazingly, startlingly accurate or so inclusive, for it seems to me almost completely inclusive in spite of your formal announcement that [pâte feuilletée] won’t be found!

This is work of the greatest integrity and I know how much of your actual life has gone into it. It should be easily recognizeable to anyone.

. . . I would like to add that I got out Knopf’s most recent entry . . . Classic French Cuisine by Joseph Donon, and that compared to you Chef Donon not only doesn’t deserve the word classic, he doesn’t even deserve the word French, in spite of his Legion of Honour!

. . . There is nothing for me to do now except wait for the executives to do their figuring.

I replied immediately, to tell her how delighted we were to be one step closer to publication and to set the record straight about my co-authors. Louisette, I explained, had suffered “family difficulties” (her husband was an ogre, it turned out, and they were getting divorced), and she had not participated much in the writing process. But Simca and I agreed on the importance of keeping Louisette “on the team,” both in deference to the work she’d done, and because of the more practical matter that she was much better socially connected than either of us, both in both France and in the U.S.A.

As for Simca, I wanted to make sure that she got proper credit for her labors. The book, I wrote, “is a joint operation in the truest sense of the word as neither of us would be able to operate in this venture without the other.” Simca wrote the entire dessert chapter and included many special twists to make traditional desserts especially delicious—including her bavarois à l’orange, her mousseline au chocolat, and her magnificent charlotte Malakoff with almonds. She had supplied us with unusual sauces, including sauce spéciale à l’ail pour gigot, sauce nénette (reduction of cream, mustard, and tomato), chaud-froid, blanche neige (cold cream aspic). It was she who worked out the secret for preventing the cream from curdling in the gratin jurassien (sliced potatoes baked in heavy cream—a trade secret from the Baumanière at Les Baux), and she who devised the triumphant recipe for ratatouille, based on her many seasons in Provence.

“It is entirely thanks to Mme. Beck and her life-long interest in cooking that we have not only the usual classical collection of recipes, but many personal and out-of-the-ordinary ones which are deeply French,” I wrote. “As far as we know, most are hitherto unpublished.”

ON NOVEMBER 6, 1959, I received a letter from Paul Brooks, the editor-in-chief of Houghton Mifflin, in the diplomatic pouch. I picked up the long white envelope and stared at it for a moment. It represented so much to me that I hardly dared to open it. Finally, I did.

The company’s executives had met several times about French Recipes for American Cooks, he wrote, and after much discussion had reached a decision:

You and your colleagues have achieved a reconstruction of process so tested and detailed that there can be no doubt as to the successful outcome of the instructions. Your manuscript is a work of culinary science as much as of culinary art.

However, although all of us respect the work as an achievement, it is obvious that . . . this will be a very expensive book to produce and the publisher’s investment will be heavy. This means that he should be able to define in advance the market for the book, to envisage a large buying public for a cookbook which will have to be high priced because of its manufacturing costs. It is at this point that my colleagues feel dubious.

After the first project grew to encyclopedic size you agreed with us that the book . . . was to be a much smaller, simpler book. . . . You . . . spoke of the revised project as a “short simple book directed to the housewife chauffeur.” The present book could never be called this. It is a big, expensive cookbook of elaborate information and might well prove formidable to the American housewife. She might easily clip one of these recipes out of a magazine but be frightened by the book as a whole.

I am aware that this reaction will be a disappointment and . . . I suggest that you try the book immediately on some other publisher. . . . We will always be interested in seeing a smaller, simpler version. Believe me, I know how much work has gone into this manuscript. I send you my best wishes for its success elsewhere.

I sighed. It just might be that The Book was unpublishable.

I wasn’t feeling sorry for myself. I had gotten the job done, I was proud of it, and now I had a whole batch of foolproof recipes to use. Besides, I had found myself through the arduous writing process. Even if we were never able to publish our book, I had discovered my raison d’être in life, and would continue my self-training and teaching. French cuisine was nearly infinite: I still had loads to learn about pâtisserie, and there were many hundreds of recipes I was eager to try.

But I felt sorry for poor Simca. She and Louisette had started this project ten years earlier, and still had nothing to show for it. “You just picked the wrong American to collaborate with,” I wrote her.

ALMOST IMMEDIATELY I got a morale-boosting letter from Avis, our tireless champion, saying: “We have only begun to fight.”

She forwarded a lovely consoling letter from Dorothy de Santillana, who wrote: “I hate to think of [Julia and Simca’s] disappointment. . . . I feel very badly to see the perfect flower of culinary love, and the solidly achieved work of so many years, go begging. They’re such nice authors.”

She went on to flesh out the actual reasons behind Houghton Mifflin’s decision. It was based on a very cut-and-dried business equation: the cost of production (very high) versus the possible sales of the book (unknown, but probably low). Our competitors were producing gimmicky cookbooks—like Houghton Mifflin’s own Texas-themed cookbook—and our more serious approach was considered too much of a risk. Even though our recipes were foolproof, the editors had convinced themselves that our dishes were too elaborate.

“All the men felt the book would seem formidable except to the professional cook, and that the average housewife would choose a competitor for the very reason that it was not so perfect,” Dorothy wrote. “They feel she wants ‘shortcuts to something equivalent’ instead of the perfect process to the absolute, which this book is. . . . This manuscript is a superb cookbook. It is better than any I know of. But I could not argue with the men as to its suitability for a housewife-chauffeur.”

Was our book ten years too late? Did the American public really want nothing but speed and magic in the kitchen?

Apparently so. The entire recipe for coq au vin in one popular cookbook, now in its third printing, read: “Cut up two broilers. Brown them in butter with bacon, sliced onions, and sliced mushrooms. Cover with red wine and bake for two hours.” Hm.

Well, maybe the editors were right. After all, there probably weren’t many people like me who liked to fuss about in the kitchen. Besides, few Americans knew what French food was supposed to taste like, so why should they want to go to all that silly trouble just to make something to eat?

As for myself, I was not at all interested in anything but French cooking. If we couldn’t find a buyer for our opus, then I would just forget about it until we returned to the States.

Charlie Child wrote consolingly: “I think Julie is a natural for TV, with or without [book] publication. But this is only one man’s opinion.” I laughed. Me on television? What an idea! We had hardly seen a single program and didn’t even own a television set.

THE EDITORS AT Houghton Mifflin had suggested we show French Recipes for American Cooks to Doubleday, a big publishing house with its own book clubs. But Avis had another idea. Without consulting me or Simca (but with our full retroactive approval), she had sent our 750 pages to an old friend, Bill Koshland, whose title was secretary at the Alfred A. Knopf publishing house, in New York.

Koshland was an accomplished amateur cook who had seen part of our manuscript at Avis’s, and had asked about it. Knopf was a prestigious house that did not have any new cookbooks on its schedule.

Losing Houghton Mifflin was a “Godsend in disguise,” Avis wrote, and publishers like Knopf had far more imagination. “This may take time but you will get published yet—I know it, I know it.”

Sleeping on it