CHAPTER 6

Mastering the Art

I. A LUCKY COINCIDENCE

IN MAY 1948, a twenty-four-year-old editor at Doubleday named Judith Bailey embarked on a three-week vacation to Europe. She and a Bennington friend sailed steerage-class from New York to Naples, and eventually made their way to Paris. It was Judith’s first visit to Europe, and she spoke only schoolgirl French, but was thrilled to be there. Her friend went home, but Judith settled into a small hotel, the Lenox, on the Left Bank, not far from where we’d eventually live on la Rue de l’Université. The days flew by, and the longer she was there the more Judith fell in love with Paris. “I have been waiting for this my whole life,” she said to herself. “I just love everything about it.”

Two days before she was scheduled to return to her job in America, Judith sat in the Tuileries Gardens reading. She had her return ticket in her purse. The sunset was so beautiful that she began to weep. “Why am I leaving?” she wondered. With a sigh, she stood up, gathered her book, and wandered off. It was only when she turned the corner that Judith realized she’d left her purse, with all of her francs, travelers’ checks, passport, and return ticket, in the garden. She rushed back, but it was gone.

She reported the robbery to the police and walked back to the Lenox without a sou to her name. “This is so strange,” she mused. “I wonder if somebody is telling me I should stay here?”

Back at the hotel, an old friend from Vermont (Judith’s native state) happened to be staying at the same hotel and noticed Judith sitting in her room with the door open. “Judith Bailey!” he exclaimed. “What are you doing here?” He and his pals took her out for dinner. Was this another sign that she should stay? She had also met a young Frenchman, who squired her about to restaurants and was a wonderful cook himself. That clinched it.

Once she had decided that she wasn’t returning to New York at all, Judith managed to find work as an assistant to Evan Jones—an American nine years her senior, who was editor of Weekend, an American general-interest picture magazine that had grown out of Stars and Stripes. Weekend did well for a time, but collapsed once the behemoths Life and Look hit the Paris newsstands. Meanwhile, Judith Bailey and Evan Jones had fallen in love.

While he wrote freelance articles and attempted a novel, Judith worked for a shady American who bought and sold cars for Hollywood stars and other wealthy expats traveling through France. She and Evan rented a little apartment and learned to cook together. Although she didn’t have any cookbooks, or the wherewithal to go to a school like the Cordon Bleu, Judith was naturally inquisitive and had a talent for the stove. Like me, she learned by tasting things—the wonderful entrecôte in restaurants, the tiny cockles in Brittany. She learned culinary trucs by asking questions of all sorts of people, such as the butcher’s wife, who showed her the perfect fat to fry pommes frites in.

During this time, Paul and I had settled into our apartment at 81 Rue de l’Université. It’s quite possible that we passed Judith and Evan on the street, or that we stood next to each other at a cocktail party, for we were leading parallel lives. But we never met in Paris.

Tired of the demanding car-dealer, Judith found new work as an editorial assistant to a Doubleday editor in Paris who was acquiring European books for the U.S. market. One day, she happened to pick up a stray book that her boss was planning to reject. Intrigued by the cover photo of a young girl, she opened the book and read the first few lines. Within pages, Judith found herself so absorbed by the story that she couldn’t put it down until she had finished it all. Feeling passionate about the book, she implored her editor to reconsider, which he did. Doubleday bought the book, and it was published it in the U.S. as Ann Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl.

By November 1951, Judith and Evan had gotten married and returned to New York. When Anne Frank became a worldwide sensation, Knopf, which had rejected the book, offered Judith a job as an editor. Her primary duty was to work with translators of French books acquired by Knopf.

In late 1959, when Bill Koshland showed our manuscript to the editors at Knopf, it was Judith Jones who immediately understood what we were up to. She and Evan tried out a few of our recipes at home, subjecting our work to the operational proof. They made a boeuf bourguignon for a dinner party. They used our top-secret methods for making sauces. They learned to make and flip an omelette the way Bugnard had taught me (they practiced the omelette flip using dried beans in a frying pan, as we had suggested, on their little deck; the following spring, they discovered beanstalks sprouting from their roof). They avidly read our suggestions on cookware and wine.

“French Recipes for American Cooks is a terrible title,” Judith said to her husband. “But the book itself is revolutionary. It could become a classic.”

Back at the office, Judith declared to her somewhat skeptical superiors: “We’ve got to publish this book!”

Angus Cameron, a Knopf colleague who had helped to launch the Joy of Cooking at Bobbs-Merrill years earlier, agreed, and together they hatched up all kinds of promotional schemes.

In mid-May 1960, I received a letter from Mrs. Jones in Oslo. Once again I found myself holding an envelope from a publisher that I hardly dared to open. After all these years of soaring hopes and dashed expectations, I was prepared for the worst but was hoping, really hoping, for the best. I breathed deeply, pulled out Mrs. Jones’s letter, and read:

We have spent months over [your] superb French cookbook . . . studying it, cooking from it, estimating, and so on, and we have come to the conclusion that it is a unique book that we would be very proud to have on the Knopf list. . . . I have been authorized to make you an offer. . . . We are very concerned about the matter of a title because we feel it is of utmost importance that the title say exactly what this book is which distinguishes it from all the other French cookbooks on the market. We consider it the best and only working French cookbook to date which will do for French cooking here in America what Rombauer’s THE JOY OF COOKING once did for standard cooking, and we will sell it that way. . . . It is certainly a beautifully organized, clearly written, wonderfully instructive manuscript. You have already revolutionized my own efforts in the cuisine and everyone I have let sample a recipe or talked to about the book is already pledged not to buy another cookbook.

I blinked and reread the letter. The words on the page were more generous and encouraging than I ever dared dream of. I was a bit stunned.

When Avis called us transatlantic, she gave a big “Whoop!” and assured us that Knopf would do a nifty printing job and would know how to really publish the book the right way.

As for the business side of things, Knopf offered us a fifteen-hundred-dollar advance against royalties of 17 percent on the wholesale price of the book (if we sold more than twenty thousand copies, we’d get a royalty of 23 percent). The book would be priced at about ten dollars, and would be launched in the fall of 1961. For simplicity’s sake, the contract would be with me, and I’d work out the financial arrangements with Simca and Louisette. Mrs. Jones didn’t care for the line drawings we had submitted (done by a friend), and would arrange to hire the best artist she could find to do our illustrations. All of these details were acceptable to us authors, and to our lawyer, and I signed the contract before anyone could have second thoughts.

There, it was done. Hooray!

Our sweet success was largely thanks to that nice Avis De Voto. She pushed and hammered and enthused for us for so long. Heaven knows what would have happened to our book if it were not for her—probably nothing at all.

It turned out that Mrs. Jones had never edited a cookbook before. Yet she seemed to know exactly what she liked in our manuscript and where she found us wanting. She enjoyed our informal but informative writing style, and our deep research on esoterica, like how to avoid mistakes in a hollandaise sauce; she congratulated us on some of our innovations, such as our notes on how much of a recipe one could prepare ahead of time, and our listing of ingredients down a column on the left of the page, with the text calling for their use on the right.

But she felt that we had badly underestimated the American appetite. “With boeuf bourguignon,” she noted, “two and a half pounds of meat is not enough for 6–8 people. I made the recipe the other night and it was superb, so much so that five hungry people cleaned the platter.” Of course, our servings had assumed that one was making at least a three-course meal à la française. But that wasn’t the American style of eating, so we had to compromise.

She also felt that we ought to add a few more beef dishes—as red meat was so popular in America—and “hearty peasant dishes.” I felt that we had quite a few peasant dishes already—potée normande (boiled beef, chicken, sausage, and pork), boeuf à la mode, braised lamb with beans, etc.—and that she was being overly romantic about this point. But after a bit of back-and-forth, we included a recipe for cassoulet, that lovely baked-bean-and-meat recipe from southwestern France.

To the untrained American ear, “cassoulet” sounded like some kind of unattainable ambrosia; but in truth it is no more than a nourishing country meal. As with bouillabaisse, there were an infinite number of cassoulet recipes, all based on local traditions.

In my usual way, I researched the different types of beans and meats one could use, and eventually produced a sheaf of papers on the subject at least two inches thick.

“Non!” Simca barked at my efforts. “We French—we never make cassoulet like this!”

She dug her heels in over the question of confit d’oie (preserved goose) in our list of ingredients. She insisted we must include it, but I pointed out that 99 percent of Americans had never heard of confit d’oie, and certainly couldn’t buy it. We wanted our directions to be correct, as always, but also to be accessible. “The important item is flavor, which comes largely from the liquid the beans and meats are cooked in,” I wrote. “And truth to tell, despite all the to-do about preserved goose, once it is cooked with the beans you may find difficulty in distinguishing goose from pork.”

Simca shook her finger at me and insisted: “There is only one way to make this dish properly—avec confit d’oie!”

This irked. “What earthly good is it for me to do all this research if my own colleague is going to just completely, blithely disregard it?” I retorted.

After much drama, we agreed on a basic master recipe for cassoulet using pork or lamb and homemade sausage, followed by four variations, including one using confit d’oie. In the book we explained the dish, gave menu suggestions, discussed the type of beans to use, and provided “a note on the order of battle.” This took nearly six pages to accomplish, but we tried to make each word count.

The title of our book caused the biggest headaches. Judith felt that French Recipes for American Cooks was “not nearly provocative nor explicit enough.” I agreed completely, which set in motion a hunt for a nifty new name. As bounty, I offered friends and family a great big foie gras en bloc truffé, straight from France. Who could resist such mouth-watering temptation? All someone had to do to claim the prize, I wrote, was to “invent a short, irresistible, informative, unforgettable, catchy book title implying that ours is the book on French cooking for Americans, the only book, the book to supersede all books, the basic French cookbook.”

My own suggestion was La Bonne Cuisine Française.

Judith felt this wouldn’t do, as a French title would be “too forbidding” for the American reader.

Some of the other early contenders included French Cooking from the American Supermarket, The Noble Art of French Cooking, Do It Yourself French Cooking, French Magicians in the Kitchen, Method in Cuisine Madness, The Witchcraft of French Cooking, and The Passionate French Cook.

As the apple trees blossomed in Oslo, and Paul and I started to grill outdoors, we debated the merits of poetic titles versus descriptive titles. Who could have predicted that the Joy of Cooking would become just the right title for that particular book? What combination of words and associations would work for our tome? We made lists and lists—The French Chef’s Companion; The Modern American’s Guide to French Cooking; How, Why, What to Cook in the French Way; Food-France-Fun—but none seemed to be le mot juste.

In New York, meanwhile, Judith was playing with a set of words like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, trying to get them to fit together. She wanted to convey our idea that cooking was an art, and fun, not drudgery; also that learning how to cook was an ongoing process. The right title would imply scope, fundamentality, cooking, and France. Judith focused on two themes: “French cooking” and “master.” She began with The Master French Cookbook, then tried variations, like The French Cooking Master. For a long time, the leading contender was The Mastery of French Cooking. (Judith’s tongue-in-cheek subtitle was: An Incomparable Book on the Fundamental Techniques and Traditional Dishes of the French Cuisine Translated into Terms of Use in American Kitchens with American Foods and American Utensils by American Cooks.) Reactions were generally enthusiastic to the title, but the Knopf sales manager worried that mastery is an accomplished thing, and that the title did not tell you how to go about mastering it. Well, then, how about How to Master French Cooking? Judith suggested.

Finally, on November 18, 1960, she wrote me to say that she’d settled on exactly the right title: Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

I loved the active verb “mastering,” immodest as it was, and instantly replied: “You’ve got it.”

At the eleventh hour, Simca declared that she did not care for the title.

“It’s too late to change it,” I said, adding that only an American ear could catch the subtle nuances of American English. Plus, I said, Knopf knew a lot more about books than we did, and they were the ones who had to sell it. So, in effect, tant pis!

Unbeknownst to us, Alfred Knopf, the imperious head of the publishing house, who fancied himself a gourmand, was skeptical that a big woman from Smith College and her friends could write a meaningful work on la cuisine française. But he was willing to give it a chance. Then, when Judith announced that we’d decided to call the book Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Alfred shook his head and scoffed: “I’ll eat my hat if anyone buys a book with that title!”

But then he acquiesced. “All right, let’s let Mrs. Jones have a chance.”

SEPTEMBER 1, 1960, marked our fourteenth wedding anniversary, but Paul and I had no time to celebrate. After eighteen years in the Foreign Service, he had decided he’d had enough and would retire. Paul could have stayed on to reach the twenty-year mark and earn three thousand dollars a month, if he wanted to. But he didn’t. It was a wrenching decision. However, once he’d made it, I noticed an immediate surge in Paul’s energy and enthusiasm.

The Knopf contract had been the impetus, but the real reason he quit was that, after twelve years of staunch effort, Paul had been rewarded with exactly one measly promotion and one disgraceful investigation. He was fifty-eight years old and sick of battling narrow-minded bureaucrats in Washington while doing yeoman’s work abroad without so much as a “thank you.” Furthermore, we both felt it was time to put down roots in our native soil and get to know our family and friends again.

We left government service on May 19, 1961—two years and two days after we had arrived in Oslo. Now we were just plain old U.S. civilians.

IN THE WEEKS leading up to our departure, I had been chewing my way through the fifteen pounds of galleys for Mastering the Art of French Cooking practically twenty-four hours a day. Proofreading was a perfectly horrible job. I was shocked to discover I’d written things like “1⁄4 cup of almond extract,” when I’d meant to say “1⁄4 teaspoon”; or had forgotten to say, “Cover the pot when the stew goes into the oven.” How could this ever have happened? Seeing one’s inadequate English frozen into type was a lesson in humility.

I worked slowly and methodically. But with an upcoming NATO conference keeping Paul fully occupied until the last moment, our imminent departure for the States, and our looming Knopf deadline, my nerves began to fray. So did Simca’s.

She was a dear friend, but horribly disorganized and rather full of herself. She didn’t bother to check the copy with care, which led to several difficult moments between us. Our deadline for proofreading was June 10, 1961. As that date drew closer and closer, a flurry of emotional letters winged between Paris and Oslo.

We debated things like a cake recipe Simca had proposed in 1959, but now, in May 1961, had second thoughts about. Noticing the recipe in the galleys, Simca declared: “Ce gâteau—ce n’est pas français! C’est un goût américain! On peut pas l’avoir dans notre livre!” (“This cake—it’s not French. It’s an American taste. We can’t have it in the book.”)

She didn’t think the cake was French, but of course it was. I spent hours checking my datebooks and notes, and reported the facts to her: “On June 3, 1959, you sent me this recipe. I tried it out, it worked well, and we agreed to incorporate it into the manuscript. On October 9, 1960, we met and discussed every recipe together, including this one. On February 20, 1961, I wrote you to confirm this.” It was too late to take an entire recipe out of the book. “What you now read in print is what you previously read and approved,” I reminded her. “I am afraid that surprise, shock, and regret is the fate of authors when they finally see themselves on the page.”

We had worked so hard, and were so close to the finish line, that our disagreements were a real strain. Yet they could not be simply brushed aside. We did our best to muddle through the give-and-take. But the clock ticked ever louder.

When Simca objected to our section on wine, I wrote back: “It cannot be as incorrect as you now think, or you wouldn’t have OK’d it before!”

I was beside myself with frustration over her dithering. To me, Mastering the Art of French Cooking was something akin to my firstborn child, and, like any parent, I wanted it to be perfect.

Wise Avis wrote: “Leave us face it. No relationship is flawless. And a relationship like yours with Simca is in many respects like a marriage. Very good ups and very bad downs. But it’s been a working relationship, and on the whole, good and productive. And the child you have produced is going to have flaws too, but will also be, on the whole, good. We must settle for what we can get.”

II. PRAWNS IN THE MAELSTROM

ONE AFTERNOON in late September 1961, I sat with a printed and bound copy of Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Beck, Bertholle, and Child in my lap. It was 732 pages long, weighed a ton, and was wonderfully illustrated by Sidonie Coryn. I could hardly believe the old monster was really in print. Was it a mirage? Well, that weight on my knees must mean something! The book was perfectly beautiful in every respect.

Our official publication date was October 16. Simca would fly to New York for the big day, and Paul and I would leave Cambridge to meet her. We planned to stay in New York for about ten days, to try to meet people in the food-and-wine game and drum up a bit of trade.

Knopf had agreed to take out a few advertisements, but most of the promotion job fell to us. I had no idea how to arrange for publicity, so I wrote friends in business and asked for advice. Frankly, I didn’t expect much. Our book was unlike any other out there, and Simca and I were absolutely unknown authors. I doubted whether any newspapers would want to write about us. Besides, I hated the whole idea of selling ourselves. We’d just grit our teeth and try our best.

And as long as we had a real live French woman in the States, we thought we ought to do a quick book tour. But how did one go about that? Simca and I decided to travel to places where we knew people who could put us up for the night and help arrange book signings, lectures, and cooking demonstrations. From New York we’d travel to Detroit, then out to San Francisco, and finally we’d descend to Los Angeles, where we’d stay with Big John and Phila.

Pop was eighty-two years old now. He hardly ever got sick, but lately had been struck by a virus and laid up in bed for two weeks. Otherwise, he had been keeping himself busy fund-raising for Nixon and fulminating against John F. Kennedy. “What this country needs is to get some real businessmen down to Washington to fix things up!” he wrote me. But I didn’t think the GOPers were the nation’s answer. Poor old Ike wasn’t very informed, and after we watched movies of the presidential debates while in Oslo, I couldn’t fathom how anyone could vote for that loathsome Nixon. “I will be voting for Kennedy,” I informed my father.

LO AND BEHOLD, in its first few weeks in print our little old book caught on in New York. Knopf was hopeful that they had a modest best-seller on their hands. They ordered a second printing of ten thousand copies, and if business continued on as it was, they were prepared to order a third printing.

Simca and I felt very proud and lucky indeed. It must have been that Mastering was published at the right psychological moment.

Writing in the New York Times on October 18, Craig Claiborne declared:

What is probably the most comprehensive, laudable and monumental work on [French cooking] was published this week. . . . It will probably remain as the definitive work for nonprofessionals.

This is not a book for those with a superficial interest in food. But for those who take fundamental delight in the pleasures of cuisine, “Mastering the Art of French Cooking” may well become a vade mecum in the kitchen. It is written in the simplest terms possible and without compromise or condescension.

The recipes are glorious, whether they are for a simple egg in aspic or for a fish soufflé. At a glance it is conservatively estimated that there are a thousand or more recipes in the book. All are painstakingly edited and written as if each were a masterpiece, and most of them are.

Ouf! We couldn’t have written a better review ourselves.

Claiborne sniffed at our use of a garlic press, “a gadget considered in some circles to be only one cut above garlic salt or garlic powder,” and thought that our lack of recipes for puff pastry and croissants was “a curious omission.” I happened to like garlic presses, but his comment about puff pastry stung a bit. Simca and I had tried and tried, but failed to come up with a workable recipe for pâte feuilletée in time for publication. But Claiborne did make special mention of our pages on cassoulet: “Anyone who attempts this recipe will most assuredly turn out a dish of a high and memorable character.” I nearly purred at that.

A few days after the Times review, Simca and I were interviewed on the radio by Martha Deane, who had a morning news-and-comment broadcast which was much listened to up and down the East Coast. It was the first time we had done anything like this, but Ms. Deane had a natural facility for putting us at ease. We had an informal chat with her for about twenty minutes, with test questions and answers, and then the tape went on and everything we said was for keeps. We didn’t worry that our words were being broadcast to the public, and just had a wonderfully good time talking about food and cooking.

Two days later, we went to the NBC studio to do a morning TV program called Today. As Paul and I didn’t have a television yet, we knew nothing about it, but the Knopf people said the show aired from 7:00 to 9:00 a.m. and was listened to by some four million people. That was a lot of potential readers.

Today wanted us to do a cooking demonstration, and we decided the most dramatic thing we could do in the five minutes allotted to us was to make omelettes. At five o’clock on the assigned morning, Simca and I arrived at the NBC studios in the dark with our black French shopping bag filled with knives, whips, bowls, pans, and provisions. It was then that we discovered that the “stove” they had promised was nothing more than a weak electric hot plate. The damned thing just wouldn’t heat up properly for an omelette. Luckily, we had brought three dozen eggs, and had an hour to experiment before the decisive moment. We tried everything we could think of, but it didn’t do much good. Finally, we decided we’d just have to fake it and hope for the best.

About five minutes before we were to go on, we put our omelette pan on the hot plate and left it there until it was just about red-hot. At seven-twelve, we were ushered onto the set. The interviewer, John Chancellor, had that same nice quality as Martha Deane—with a deft verbal touch, he put us at ease and bolstered our confidence so that Simca and I had such a good time we didn’t care what happened. Well, by heaven, if that one last omelette didn’t work out perfectly! The Today show went better than we could have hoped for, and it was over before we knew it. We were impressed with the informal and friendly atmosphere of the NBC chaps, not to mention their perfectly timed professionalism. TV was certainly an impressive new medium.

The old publicity express was rumbling along at a good clip now. Somehow, Life magazine learned of our book and mentioned it in their pages. Then Helen Millbank, an old Foreign Service friend, arranged to have Simca and me photographed for Vogue, where she worked—ooh-la-la! And the best news of all was that House & Garden, which had an excellent cooking supplement, asked us to write an article. This was a great boon, as that magazine is where all the fancy food types, like James Beard and Dione Lucas—the English chef and teacher, who had a TV cooking show—appeared.

One night while in New York, we met James Beard, the actual, large, living being, at his cooking school/house at 167 West Twelfth Street. Simca and I felt immediately fond of Jim, as he insisted we call him, and he kindly offered to do what he could to put Mastering on the culinary map. He was a man of his word, and introduced us around town to culinary movers-and-shakers, like Helen McCulley, a tiny gray-haired fireball who was the editor of House Beautiful. She, in turn, introduced us to a number of chefs, like a young Frenchman named Jacques Pépin, a former chef for de Gaulle who was cooking at Le Pavillon restaurant. And we also met Dione Lucas at the Egg Basket, her little restaurant that had a cooking school in the back. Simca and I sat at the omelette bar, where Lucas put on a wonderful performance while giving us lunch and pointers on doing cooking demonstrations for an audience.

In early November, we flew from Boston, where it was eighty-two degrees, to Detroit, where it was snowing. We stayed in Grosse Pointe with socially prominent friends of Simca’s, who invited a big crowd to our demonstration. Although most of the people there knew nothing about la cuisine française, they liked our book enough (or followed the herd enough) so that it sold out in local bookstores. We had no idea if these sales had any wider significance, but it was a pleasant surprise in Detroit. It would have been awful to be on a promotion trip for a dead, or dying, duck!

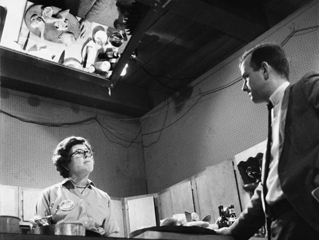

Simca and I being interviewed by Rhea Case at the Cavalcade of Books in Los Angeles

Then on to California, where San Francisco was brilliantly sunny, diamond-clear, cool, and green. On a typical day, we were picked up at nine-forty-five at Dort’s house in Sausalito by the local Knopf representative, a Mr. Russell. He drove us to an interview at the Oakland Times. Then to the Palace Hotel in San Francisco by noon, where we were interviewed on KCBS Radio. By this point, we were getting much better at answering interviewers’ questions, talking more slowly and clearly, and not feeling self-conscious. It was fascinating to see how the radio and newspaper people went about their work. After a quick lunch, Russell drove us back to Sausalito, where we barely had time to wash our hands before Paul and I climbed aboard Dort’s Morris Minor and drove to Berkeley. There we had a sort of “diplomatic” tea with a Mrs. Jackson, a children’s-book author and wife of a famed book editor. Then back to Dort’s, where we picked up Simca, and drove into San Francisco for a cocktail party with a mob of university types. Then dinner with a woman who would host a book party for us in Washington, D.C., and who would try to persuade the Washington Post to write something about Mastering the Art of French Cooking. After dinner we called on an older woman friend, as vigorous as a pirate, and we finally made it home by eleven-thirty. Whew!

On another day, Simca and I set up a stove on the fifth floor of a big department store called the City of Paris, and spent from 10:00 a.m. until 4:00 p.m. making omelettes, quiches, and madeleines, again and again. Screaming at the top of our lungs in order to be heard, we worked practically non-stop and subsisted on whatever we made. It was fun, although we felt like pawns, or prawns, in the maelstrom.

This sort of life was fine for six weeks, but I would not like to be stuck in it continuously. It left no time for work.

When we quit the Foreign Service, Paul and I had said, “Ah, freedom at last—no more of this hurly-burly, thank you very much!” But here we were, shuttling from place to place and hitting deadlines with just seconds to spare. Paul, with his years of experience in exhibits and presentations, helped us immeasurably. Not that Simca and I couldn’t take care of ourselves, but to have someone along who didn’t have to think about cooking and talking, and who could devote himself entirely to wrangling microphones, stage lights, tables, ovens, etc., allowed us to concentrate on the job at hand.

Just to keep things interesting, we were all ailing—Simca had a leg swell up, Paul suffered a major toothache, and I had a touch of cystitis. “One thing that separates us Senior Citizens from the Juniors is learning how to suffer,” Paul noted. “It’s a skill, just like learning to write.”

By the time we arrived in Los Angeles, Pop had recovered from his flu enough to toss off a few verbal stinkbombs. He needled us as usual about “those people” (i.e., the French), about “the socialist labor unions” (he hated all unions), and about “the Fabian Society in Cambridge” (he disdained the politics of his elder daughter and son-in-law). His views, and general ignorance, were not uncommon in Pasadena. “I’ve never heard of the Common Market; what is it?” asked a nice and well-educated friend of my parents, a statement that shocked me. Maybe we had lived outside of the U.S.A. for too long, but many of our fellow citizens seemed blissfully unaware of world politics or culture, and seemed exclusively interested in business and their own comfort.

I began to feel nostalgic for Norway, with its good sturdy folk, its excellent educational system, its unspoiled nature, its lack of advertising, and its non-hectic rhythms.

At a cooking demonstration for a women’s group in Los Angeles, two ovens, a range, an icebox, and a table, above which was a large mirror tipped at a forty-five-degree angle had been set up, so that the audience could watch our hands and see right into the pots as Simca and I cooked. Unfortunately, the club’s leader hadn’t bothered to get a single item on the shopping list we had sent her weeks ahead of time. Suspecting as much, we arrived at the theater an hour and a half early, which gave us just enough time to scrounge up the three garbage pails, five tables, rented tablecloth, buckets of ice water, soap, towels, implements, and other items we needed for our demonstration. And it was a good thing, too. About 350 women attended the morning show, and another three hundred arrived in the afternoon. Simca and I demonstrated how to make quiche au Roquefort, filets de sole bonne femme, and reine de Saba cake. All went smoothly. In between shows, we signed books, sat for interviews, and made the right noises to dozens of VIPs. Meanwhile, the esteemed former American cultural attaché to Norway was crouched behind some old scenery flats trying to wash out our egg- and chocolate-covered bowls in a bucket of cold water.

By December 15, we were back in New York, where generous Jim Beard hosted a party for us at Dione Lucas’s restaurant, the Egg Basket. We invited thirty guests, mostly those who had been instrumental to our success, including Avis De Voto, Bill Koshland, and Judith and Evan Jones. Jim saw to it that a small but influential group of food editors and chefs were invited: Jeanne Owen, executive secretary of the Wine and Food Society; June Platt, a cookbook author; and Marya Mannes, a writer for The New Yorker.

Dione Lucas had once run the Cordon Bleu’s school in London, but she didn’t strike us as especially organized, or sober. A few days before the party, the menu hadn’t been finalized and arrangements for the wine delivery had yet to be made. Paul and I made an appointment to discuss these details with Ms. Lucas, but when we arrived the Egg Basket was closed and dark. Tacked to the locked door was a note, saying something like “Terribly sorry to have missed you, my son is ill, very ill . . .” Hm. When Judith Jones had lunched at the restaurant two weeks earlier, Lucas had been missing due to “a migraine.”

No matter. Simca and I pitched in, and prepared a braised shoulder of lamb at my niece’s apartment a few blocks away. Dione Lucas finally appeared, and made a good sole with white-wine sauce, salade verte, and bavarois aux fraises. The wine arrived intact from Julius Wile, the famous vintner, who was a lively presence. And Avis declared the event “snazzy.”

The highpoint of the evening came when Jim Beard stood up and toasted me and Simca with the highest compliment imaginable: “I love your book—I only wish that I had written it myself!”

III. I’VE BEEN READING

POP WAS DYING. He had never fully recovered from his flu, and in January 1962 he was hospitalized with a bad mystery ailment: spleen swollen, high white-corpuscle count, perhaps pneumonia. Many tests had revealed little information, although the doctors suspected that they’d found a small tumor at the bottom of his lungs. Phila, one of her daughters, and Dort took turns keeping an eye on him in the hospital. If things took a turn for the worse, I had packed a bag and was ready to fly to Pasadena at a moment’s notice.

In the meantime, Mastering was in its third printing of ten thousand copies, and I’d received our first royalty payment, a check for $2,610.85. Yahoo! I did some quick calculations, and discovered we were within $632.12 of paying off all of our book expenses. Soon, we would be able to send some real cash money to ma chérie, Simca.

John Glenn had circled the globe in his little space capsule (we still didn’t have a TV set, and Paul was glued to the radio all day), and I had been invited to go on an egghead television show in Boston to talk about food and Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

The show was called I’ve Been Reading, and it was hosted by Professor Albert Duhamel on WGBH, Channel 2, the local public television station. (This lucky break was thanks to our friend Beatrice Braude, who had worked for USIA in Paris, got chewed up by the McCarthy bullies, and now worked as a researcher at WGBH.) I was told that it was unusual for Professor Duhamel to invite a food person on I’ve Been Reading, so my expectations were low. But the interview went extremely well. Instead of the usual five-minute spot, we were given a full half-hour. I didn’t know what we’d talk about for that long, so I arrived with plenty of equipment. They had no demonstration kitchen, and were a little surprised when I pulled out a (proper) hot plate, copper bowl, whip, apron, mushrooms, and a dozen eggs. Before I knew it, we were on the brightly lit set and on the air! Mr. Duhamel was calm, clear, and professional; it helped that he loved food and cooking, and had actually read our book. After chatting with him for a bit, I demonstrated the proper technique for cutting and chopping, how to “turn” a mushroom cap, beat egg whites, and make an omelette. There was a large blowup of Mastering’s dust jacket projected on a screen behind me, but I was so focused on demonstrating proper knife technique that I completely forgot to mention our book.

Ah me, I had so much to learn!

In response to that little book program, WGBH received twenty-seven more or less favorable letters from viewers. I don’t think one of them mentioned our book, but they did say things like “Get that woman back on television. We want to see some more cooking!”

BY THE END OF February, the renovation of our kitchen at 103 Irving was finished, and it was a good-looking workroom. We had raised the counters to thirty-eight inches all around, carved out more storage space, and added lights over the work surfaces. Paul chose an attractive color scheme of light blue, green, and black. I hated tile floors, which hurt my feet, so we laid down heavy vinyl, the kind used in airports. There was a thick wood butcher’s-block counter and a stainless-steel sink. We had an electric wall oven, and nearby was the professional gas range, in a corner by the door. Over the stove we installed a special hood with two exhaust fans and a utensil rack.

Finally, I arranged all of my pots and pans on the floor the way I liked, and Paul drew their outlines on a big pegboard, so you would know where each one went. Then he mounted the pegboard on the wall, which made my gleaming batterie de cuisine look especially handsome.

The kitchen was the soul of our house. This one, the ninth that Paul and I had designed together, was a real wowzer, a very functional space and a pleasure to be in.

While I banged away at recipes suitable for a Washington hostess party for House & Garden, Paul devoted an entire day to fixing up a closet in the cellar as a wine cave. He even drew up an elaborate chart showing exactly how many bottles of which vintage he had in stock. But when he opened up the cases we’d sent from Norway, he found five bottles had broken—including a fine 1835 Terrantez Madeira, a loss which hurt. “Why did that one have to break and not one of the bottles of Jean Fischbacher’s homemade marc, a fire-water that I detest?” he wailed. “Oh, the injustice.”

Mastering the Art of French Cooking continued to sell. With our first royalty check, we bought a book on how not to let plants die (for me), a dry-mount press (for Paul), and the latest edition of Webster’s dictionary (for both of us), which led us to scream at each other about the proper use of language. He was a language-by-use type, while I was an against-the-prostitution-of-language type. We also bought our first television set, a smallish square plastic-and-metal box that was so ugly we hid it in an unused fireplace.

Encouraged by the response to our little cooking demonstration on I’ve Been Reading, the honchos at WGBH asked me and the show’s director, twenty-eight-year-old Russell Morash, to put together three half-hour pilot programs on cooking. The station had never done anything like this before. But if they were willing to give it a whirl, then so was I.

MY FATHER DIED on May 20, 1962. In the preceding weeks he had lost forty-eight pounds and had grown white and frail; he was a ghost of his former self. The diagnosis was lymphatic leukemia. Dort, John, and I had arrived in L.A. just before he passed away.

I was fond of Pop, in a way. He had been terribly generous financially, but we did not connect spiritually and had become quite detached. He never said much about my years of cookery-work, our book, or my appearances on radio and television. He felt that I had rejected his way of life, and him, and he was hurt by that. He was bitterly disappointed that I didn’t marry a decent, red-blooded Republican businessman, and felt my life choices were downright villainous. From my perspective, I did not reject him until the point when I could no longer be honest about my opinions and innermost thoughts with him, especially when it came to politics. As I looked back on it, I think that break—my “divorce” from my father—began with our move to Paris.

I really loved my mother, Caro, and missed her. She was a warm and very human person, though non-intellectual. She died when I was still a semi-adolescent. Yet she—and so many other good people in Pasadena, including Phila—just adored Pop, so he must have had something in there. He had lots of good friends, helped many people, spent hours fund-raising for the Pasadena Hospital and other do-gooding organizations. But he did not communicate well with his children. He was no more sympathetic or decent to John and Dort than he was to me.

I know there were times I could have been better, nicer, more generous toward him, and so forth and so on. But, frankly, my father’s death came as a relief more than a shock. I suddenly felt we could go to California whenever we wanted to, without restraints or family trouble.

Big John had not been a churchgoer, so we held his memorial service at the house in Pasadena. About two hundred people were there, and so was his coffin. Phila remained strong and composed throughout. There was a short reading, a hymn or two sung, no eulogy. His body was cremated. We had found his father’s ashes in a cardboard box behind a living-room sofa. On a calm bright day, we took the ashes of my grandfather, my mother, and my father on a sailboat out by Catalina Island and strewed them into the sea. My brother read from the Episcopal burial-at-sea service. A few tears were wiped away. Eh bien, l’affaire conclue.

IV. THE FRENCH CHEF

I KNEW NOTHING at all about television—other than the running joke that this fabulous new medium would thrive on how-to and pornography programs—but in June 1962 I taped the three experimental half-hour shows, or pilots, that WGBH had suggested.

WGBH, Channel 2, was Boston’s fledgling public TV station. It didn’t have much mazuma and was mostly run by volunteers, but they had managed to cobble together a few hundred dollars to buy some videotape. Russell (Russ) Morash, producer of Science Reporter, would be our producer-director, and Ruthie Lockwood, who had worked on a series about Eleanor Roosevelt, would be our assistant producer. Ruthie scrounged up a sprightly tune to use as our theme song. And after considering dozens of titles, we decided to call our little experiment The French Chef until we could come up with something better.

Now, would there be an audience out there in TV Land for a cooking show hosted by one Julia McWilliams Child?

The odds were against us. Jim Beard had done some experimental cooking shows sponsored by Borden’s Elsie the Cow, but although he had trained as an actor and opera singer, he came across as self-conscious on television. He would spend long silent periods looking down at the food and not up at the camera; or he’d say “Cut here,” without explanation, rather than, “Cut it at the shoulder, where the upper arm joins.” Unfortunately, his shows never drew a large audience. Dione Lucas had also done a TV series, but, alas, she was never comfortable in front of the camera, either. Her show fizzled, too.

Our plan was to show a varied but not-too-complicated overview of French cooking in the course of three half-hour shows. We knew this was a great opportunity for . . . something, none of us was exactly sure what.

Through some kind of dreadful accident, WGBH’s studio had burned to the ground right before we were going to tape The French Chef (my own copy of Mastering went up in smoke, too). But the Boston Gas Company came to our rescue, by loaning us a demonstration kitchen to shoot our show in. So that we could rehearse, Paul made a layout sketch of the freestanding stove and work counter there, which we brought home and roughly emulated in our kitchen. We broke our recipes down into logical sequences, and I practiced making each dish as if I were on TV. We took notes as we went, reminders about what I should be saying and doing and where my equipment would be: “simmering water in large alum. pan, upper R. burner”; “wet sponge left top drawer.”

My trusty sous-chef/bottle-washer, Paul, had his own notes, for he would be an essential part of the choreography behind the camera: “When J. starts buttering, remove stack molds.”

There. We had done as much preparation as we could. Now it was time to give television a whirl.

ON THE MORNING OF June 18, 1962, Paul and I packed our station wagon with kitchen equipment and drove to the Boston Gas Company in downtown Boston. We arrived there well ahead of our WGBH crew, and quickly unloaded the car. While Paul parked, I stood in the building’s rather formal lobby guarding our mound of pots, bowls, whisks, eggs, and trimmings. Businessmen in gray suits and office girls rushed in and out of the lobby, eyeing me with disapproval. A uniformed elevator operator said, “Hey, get that stuff out of this lobby!”

But how were we to get all of our things down to the demonstration kitchen, in the basement? Resourceful Paul found a janitor with a rolling cart, which we filled with our household goods and clanked down the stairs to the kitchen. There we set ourselves up according to our master plan.

With Russ Morash on the set of The French Chef

Our first show would be called “The French Omelette.” Ruthie Lockwood arrived, and we went over our notes and set up a “dining room” for the final scene, where I would be shown eating the omelette. Russ and the camera crew arrived, and we did a short rehearsal to check the lighting and camera angles. He was using two very large cameras, which were attached by thick black cables that snaked up the stairs and out to an old Trailways bus equipped with a generator.

A live show was out of the question—partly due to the limitations of equipment and space, and partly because I was a complete amateur. But we decided to tape the entire show in one uninterrupted thirty-minute take, as if it were live. Unless the cameras broke or the lights went out, there would be no stopping or making corrections. This was a bit of a high-wire act, but it suited me. Once I got going, I didn’t like to stop and lose the sense of drama and excitement of a live performance. Besides, our viewers would learn far more if we let things happen as they tend to do in life—with the chocolate mousse refusing to unstick from its mold, or the apple charlotte collapsing. One of the secrets, and pleasures, of cooking is to learn to correct something if it goes awry; and one of the lessons is to grin and bear it if it cannot be fixed.

When we were more or less ready, Russ said: “Let’s shoot it!”

I careened around the stove for the allotted twenty-eight minutes, flashing whisks and bowls and pans, and panting a bit under the hot lights. The omelette came out just fine. And with that, WGBH-TV had lurched into educational television’s first cooking program.

The second and third shows, “Coq au Vin” and “Soufflés,” were both taped on June 25, to save money. We had more time to rehearse these shows, and they went smoother than the first one. Once we had finished taping, our technicians descended on the coq au vin like starving vultures.

On the evening of July 26, we ate a big steak dinner at home and, at eight-thirty, pulled our ugly little television out of hiding and switched on Channel 2. There I was, in black and white, a large woman sloshing eggs too quickly here, too slowly there, gasping, looking at the wrong camera while talking too loudly, and so on. Paul said I looked and sounded just like myself, but it was hard for me to be objective. I saw plenty of room for improvement, and figured that I might begin to have an inkling of what I was supposed to do after I’d shot twenty more TV shows. But it had been fun.

The response to our shows was enthusiastic enough to suggest that there was, indeed, an audience for a regular cooking program on public television. Perhaps our timing was good. Since the war, more and more Americans had been traveling to places like France and were curious about its cuisine. Furthermore, the Kennedys had installed a French chef, René Verdon, in the White House. Our book continued to sell well. And television was becoming a hugely popular, and powerful, medium.

WGBH boldly suggested that we try a series of twenty-six cooking programs. We were to start taping in January, and the first show would air in February 1963. And with that, The French Chef, which followed the ideas we’d laid out in Mastering the Art of French Cooking, was under way.

V. LA PEETCH

IN 1963, I was shooting four episodes of The French Chef a week while also writing a weekly food column for the Boston Globe. In the fall, we were scheduled to take a break from TV work, and had planned to visit Simca and Jean at their rambling farmhouse in Provence. But as November hove into view, we began to regret it. The quicksand of my cookery-work, Paul’s painting and photography projects, and all the many bits of upkeep and improvement that 103 Irving Street required were sucking at our feet.

“I just don’t know if we have the time for a trip to France right now,” I sighed. Paul nodded.

But then we looked at each other and repeated a favorite phrase from our diplomatic days: “Remember, ‘No one’s more important than people’!” In other words, friendship is the most important thing—not career or housework, or one’s fatigue—and it needs to be tended and nurtured. So we packed up our bags and off we went. And thank heaven we did!

On the terrace at Bramafam

Jean and Simca had been spending more and more time lately at their early-eighteenth-century stone farmhouse, Le Mas Vieux, on a Fischbacher family property known as Bramafam (“the cry of hunger”). It was up a rutted dirt driveway on the slope of a dry, grassy hill outside the little town of Plascassier, above Cannes. In front of the house stood a lovely tree-shaded terrace that looked across a valley toward the flower fields and tall, swaying cypress trees of Grasse, an area famous for its perfumes.

Le Mas Vieux had been inhabited for twenty-nine years by Marcelle Challiol, a cousin of Jean’s, and Hett Kwiatkowska, two women painters who had passed away. Now the house was falling apart. It was extremely rustic, and Simca didn’t care much for it at all. But Jean loved it as a retreat from the pressures of perfumery in Paris. Every morning he liked to putter about his garden dressed in a blue bathrobe, whistling tunes and talking to his flowers. As they slowly renovated, adding more rooms, light, and heat, and updating the bathrooms, the old manse slowly won Simca over. As she oversaw renovations, she discovered a small leather sack buried under the stairs; inside of it were a few Louis XV silver pieces, dating to 1725—“which proves its age,” she liked to say. Once all the work was done, Simca discovered that Le Mas Vieux was the perfect place for her to cook, teach, and entertain friends. Suddenly it began to sound as if the renovations had been her idea.

Bramafam was gorgeous in November, with lavender bushes and mimosa all about. One afternoon, the four of us shared an idyllic lunch of Dover-sole soufflé with a chilled bottle of Meursault on the terrace. As we sat contentedly in the sun, breathing in the soft, flowery aromas, Paul and I bandied about the idea of buying a simple place of our own nearby. We even took a look at a few properties in the area, but nothing was quite right for us, or quite affordable. Then Jean suggested that we build a small house on a corner of his property. What an idea!

The more we talked about it, the more excited we became. As I’ve mentioned, Paul and I had long hoped to buy a pied-à-terre in Paris, or to build a little getaway cabin somewhere—perhaps in Maine (near Charlie and Freddie), or California (near Dort), or even in Norway (which we still romanticized). But to be in Provence next to Simca would be a dream come true. I could already imagine spending my winter months here, curing the olives from our trees, and cooking à la provençale, with garlic, tomatoes, and wild herbs.

Le Mas Vieux sat on about five hectares of land. Jean didn’t want to sell off any of the family property, so Paul and I agreed to lease what used to be a potato patch from them, about one hundred yards away from Le Mas Vieux, to construct a house on. Once we had finished using it, the property would revert to the Fischbacher family, with no strings attached. The agreement was made with a handshake. It would be a house built on friendship.

Paul and I envisioned a very simple structure in keeping with the local architecture: a single-level house, with stucco walls and a red-tiled roof. Simca and Jean offered to oversee the construction while we were in the States, and Paul opened a line of credit for them at a nearby bank. We found an accomplished local builder, although Paul had to use every bit of his diplomatic training to convince the man that we did not want a palazzo, but a simple, modest, and as-maintenance-free-as-possible house.

We decided to call it La Pitchoune, or “The Little Thing.”

Building La Pitchoune

BY 1964, Mastering the Art of French Cooking—or MTAFC, as we called it—was about to go into its sixth edition (and we were still finding silly errors and making corrections), while The French Chef could be seen on public television in more than fifty cities, from Los Angeles to New York. On the spur of the moment, I had decided to end each show with the hearty salutation “Bon appétit!” that waiters in France always use when serving your meal. It just seemed the natural thing to say, and our audience liked it. Indeed, I found that I rather enjoyed performing and was slowly getting the hang of it.

The combination of book and TV work, along with the occasional article or recipe, had turned me into a budding celebrity. There were magazine stories about our show, about our home kitchen, about how and where we shopped, and so on. My cooking demonstrations drew larger and larger crowds. “Julia Watchers” began to recognize me on the street, or called our house, and wrote us letters. At first this kind of attention was strange, but I soon adapted (though Paul resented it). I learned not to lock eyes with staring strangers, which only encouraged them. I have always been a ham, but I didn’t care much about celebrity one way or the other.

Hardly anyone in France had heard of The French Chef, or knew anything about me. I never really discussed the show’s success with Simca: it didn’t seem important, and I didn’t want her to feel overshadowed. I felt that she was such a colorful personality, and so knowledgeable about cooking, that had she been American rather than French she would be immensely well known.

In February 1964, we flew to Paris, and I dropped in on classes at L’École des Trois Gourmandes, ate out with friends, and visited Bugnard—who was as jolly as ever, though crippled by arthritis. Then Paul and I rented a car and drove south to check on the construction of La Pitchoune. I had no worries about the quality of work, as I knew Simca had been hovering over the project like a mother hen over her nest, and had kept a sharp Norman eye on the schedule and costs.

The house was still in a rudimentary condition when we arrived, but I was smitten with “La Peetch” right away. We made a few final decisions on the interior: there would be red tile floors, a fireplace in the long living/dining room, a hallway with a smallish kitchen and my bedroom on the left, and a guest room and Paul’s bedroom on the right. (He was a sometime insomniac, and I was known to snore. We decided it was best to spend the nights apart, but we’d put a double bed in Paul’s room so that we could cuddle in the mornings.) My room would have a desk and bookshelf; his would have a little fireplace and French doors that opened onto a stone-and-concrete terrace.

“Even in its unfinished state,” I wrote Avis, “the house is a jewel.”

NINETEEN SIXTY-FIVE was even more hectic than the year before. Paul and I spent long hours with our production team in Boston, working out the scripts and shooting French Chef programs at WGBH. In this intensive period, I could feel that I was slowly improving my TV presentation skills. But by the end of the year, Paul and I were both itching to bust out of our same old routine. On the spur of the moment, we decided to spend Christmas in France. “La belle F.,” we called it: France was our North Star, our spiritual home. Charlie and Freddie joined us, and we all sailed from New York to Le Havre, then trained it south from Paris to Nice. At the terminus, we rented a little tin-can-type car, and put-putted slowly to Bramafam.

As we turned in at the gate and bumped our way up the dusty driveway, we saw, with mounting excitement, a new house on the right-hand brow of the hill. La Pitchoune—it was finished!

The little house was just as we’d dreamed it would be: tan stucco walls, red-tiled roof, two chimneys, wooden shutters, and a stone terrace. The lights were all turned on. The refrigerator was fully stocked. The windows had curtains. The living room had comfortable chairs. The beds were made up with brand-new sheets. It was chilly outside, but the house had plenty of heat and hot water. Best of all, a great potée normande awaited us on the stove. All we had to do was walk inside.

Simca and Jean had been so thoughtful.

A week later, Les Childs and Fischbachers celebrated the New Year together at La Peetch, with a feast of oysters, foie gras, and Dom Pérignon. By that time, Paul and Charlie had mounted pegboard on the kitchen wall, outlined my pots and pans, and hung the batterie de cuisine. It did my heart good to see rows of gleaming knives and copper pots at the ready. I could hardly wait to get behind the stove.

Paul and I stayed in our satisfying little house for three months, slowly settling into the sedate rhythms of Provence. La Peetch was set into a hill that had been terraced with low stone berms and was studded with olive trees, almond trees, and lavender bushes. The top of the driveway was just big enough to turn around a compact French car in. Our water came from a large concrete tank behind the house. A spreading mulberry tree hung over the terrace. Before Charlie and Freddie returned to Lumberville, they helped us to frame the terrace with olive trees and mimosas. And we partially renovated a small stone shepherd’s hut, the cabanon, to use as a combination wine cave/painting studio/guest room.

Simca and Jean had returned to Paris in early January, but she and I wrote back and forth constantly, trading recipes and comparing notes. It was high time, we had decided, to write Mastering the Art of French Cooking, volume II.