The Greatest Day

At exactly “shortly,” the entire staff of Oliver Wright’s armor factory was still standing and waiting in stunned silence.

No one in the village had ever before come so close to anyone so close to the King. Except perhaps for the knight who was sent to purchase the King’s armor. But he had hardly said a word—and maybe that was just a story. Maybe he had nothing to do with the royal family.

This was different: the beautifully clean uniforms, the rare sound of trumpets, and the chance to see and hear King John’s own officer-of-arms.

At shortly and a half, a large, bearded man walked past the herald and through the two rows of trumpeters. His tabard, or sleeveless coat, was covered in big swirls of gold embroidery. On the front and back was the royal coat of arms.

Roland wouldn’t have believed anyone could have a louder voice than the herald of the royal castle. But the officer-of-arms did. He held a long scroll of paper and proclaimed in a beautifully clear but horribly loud voice: “Hear ye, hear ye, hear ye!”

“Why does he repeat himself?” Roland asked his brother. “We heard him loudly enough the first time.”

“Be quiet,” said Shelby. “That’s the way they say it to make it important and official.”

“Hear ye, hear ye, hear ye!” the officer-of-arms said again. “His Majesty King John has sent me on his behalf to convey a message to Mr. Oliver Wright. The message is this: In the recent Battle of Two Tree Hill, your King again fought bravely and nobly for his subjects, riding with the front line. During the fight he was struck in the shoulder by a poisoned bolt fired from a crossbow.

“The bolt hit the joint, the place where armor is normally the weakest. But it did not pierce the steel.

“After the battle was won, the King asked his blacksmiths to look at his suit of armor, stamped with the simple imprint ‘Wright.’ They said what saved His Majesty’s life was the simple, strong design and the fact that it was plate steel all over.”

Roland gasped. So it was true. The King did have a set of his father’s armor. The officer-of-arms kept talking.

“His Majesty would like to convey his gratitude to the maker of this armor. What is more, the King wishes to show this gratitude. He will do this in two important ways. Firstly, by allowing Mr. Oliver Wright to stamp on all the armor he makes the words ‘By Royal Appointment.’”

Roland turned to Shelby. “‘By Royal Appointment.’ That’s going to be hard to spell.”

“Quiet!” snapped Shelby.

“Secondly,” the officer-of-arms continued, “he has learned that Mr. Oliver Wright has two sons. His Majesty will take one of these two sons into the royal household to be trained as a page.

“It is a great honor for the son who is chosen, and the King is sure that if the son has the qualities of his father, he will not let His Majesty down.”

Roland started shaking with excitement.

“Flaming catapults, Nudge,” he whispered to his top pocket. “I can’t believe this, and I am sure you can’t either. This means I will become a page. And if I become a page, Nudge, I can become a squire. And if I can become a squire, I can become a knight. And if I can become a knight I will get a real suit of armor, a real warhorse, a real lance for jousting and a real-life, big, spiky steel mace.”

The officer-of-arms continued talking, but Roland was no longer listening. He was too busy thinking how proud he was of his father, and how proud his father would be when Roland learned to read, to hunt with falcons, to play a musical instrument, to ride a horse and to do all the other things a page was taught to do.

“This is the most important day of my life, Nudge,” he whispered. “I will learn all about swords and longbows and crossbows and all sorts of other weapons. And you will come with me!”

Then Roland looked across the forge and saw his brother. “We’re just lucky, Nudge, that Shelby is going to take over the business.”

Roland looked through the doorway to see that many people from the village had walked across the square to see what the hullabaloo was about. Farmer Jones was there with his cow, and Jenny Winterbottom was there with her mother, who always wore a white wimple and smelled strongly of lavender. Mrs. Winterbottom had large eyes and a sharp, pointy nose like a sparrow hawk. She looked at everything now happening in front of her and started shaking her head and saying “Dear, dear, dear.”

The final words of the officer-of-arms were: “Now the King orders you all to feast,” and with that he turned and left the forge, followed by the herald and the six trumpeters.

Suddenly four men in white uniforms climbed out of a tall brown wagon that had appeared in the village square. They carried a large cooked animal on a round silver tray.

The animal was roasted to a golden brown color, and was the strangest thing that Roland had ever seen. It had a head and shoulders like a rooster but the body of a piglet. It also had small wings, still covered in feathers.

“A flying pig?” Roland couldn’t believe it. He turned to Shelby. “A capon with the body of a hog? Where does such a beast live?”

“You fool,” said Shelby. “It’s a cockentrice. It’s what rich people eat. Cooks take half of one creature and sew it to half of another to make a pretend new animal. They mix all the meat together and stuff it and roast it.”

“How do you know these things?” asked Roland.

“Older brothers know everything.”

The workers began to clap and cheer Oliver Wright, while the chefs sliced their creation.

“Bravo, good ’ealth to you, Mr. Wright,” yelled Mr. Nottingham, the mail-maker. It was a bit hard to understand him, though. His mouth was already filled with roostig—or was it pigster?

“And I should add that I’ve never tasted meat ’alf as rich as this,” Mr. Nottingham spluttered, “with so many fruits and ’erbs and spices in it too.”

Just as Mr. Nottingham spoke, Roland felt his father’s big powerful arm wrap around his shoulder. He looked up to see Shelby under his father’s other arm. Mr. Wright, who so rarely showed his feelings, was smiling what for most people would be a small smile. But it was the biggest smile that his sons had ever seen Mr. Wright smile.

“Well done, everybody,” said Mr. Wright. “It is an immense honor. But we all make the armor together, so it is something we can all be proud of. And those of you who haven’t already partaken of the cockentrice, please do so.”

Sir Gallawood, who had waited around to hear the officer-of-arms, began clapping again at the end of Mr. Wright’s short speech.

“Already I have a second reason to say well done, my good man,” Sir Gallawood said. He then turned to the crowd and said in a large, knightly voice: “It is a wonderful thing to save a king.”

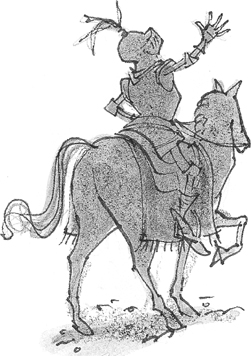

Sir Gallawood lifted his repaired helmet back onto his head. He jumped onto his horse, lifted his visor and looked straight at Oliver Wright and his two sons. “And if there is anything I can do to help any of you, let me know.”

“How about not punching me again,” thought Roland, but he didn’t say it out loud. He liked Sir Gallawood even more now that he had met him, and anyway, this was the greatest day of Roland’s life. What did a sore shoulder matter?

When Sir Gallawood rode off, Mr. Wright turned to Roland, who was now trying to see how much cockentrice he could fit into his mouth. Mr. Wright’s smile was gone. He was back to his usual self.

“Well, that’s enough exhilaration for now,” said Mr. Wright. “Eat up nice and quick. And make sure your friend Jenny gets some too.”

“She’s not my friend,” said Roland. “She’s our neighbor.”

“Well, either way, it’s a busy day, son.”

“But can’t we talk, Father, can’t we talk?” Roland was almost shrieking with excitement. His father’s eyes seemed to move closer together and his forehead scrunched up. It was the Look. Without words, the Look said that there was going to be no more talking from Roland and a lot more working.

“You can start, Roland, by bringing in the coal. Then you can sweep up the metal filings so we can reuse them. And when Shelby has accomplished his tasks, then I’ll sit you both down and explain what we should do about King John’s offer.”

Roland already knew what they should do. They should say “Yes” straightaway and send Roland directly to the royal household. As he carried in the big lumps of coal needed to keep the smith’s furnace burning and stacked them high, Roland thought of nothing else.

“Isn’t it wonderful?” he said to Shelby, who had gone back to oiling hinges. “I’m going to be the best page in the world, then the best squire, then the best knight.” Shelby looked up with surprise and anger. “You? You? What do you mean you?”

“Well, you are going to take over the armor business, like you always say, and I—”

“That was then,” sneered Shelby. “Now everything has changed. I’m the oldest, I’m better at doing things. So it will be me, not you, Roland, who will live at the King’s castle. It will be me who will eat a whole cockentrice at supper every night—and it will be me who will sleep on a bed of softest duck feathers.”