Here’s a very, very brief summary of North American prehistory, providing some general anthropological and historical context for the sites we’ll be visiting in this book. Think of this as the equivalent of “Shakespeare in 5 Minutes.”

To begin, all American Indians are related biologically, culturally, and historically, but they are not all identical peoples bearing exactly the same culture. It’s like Europe: The people who live there are all Europeans, but they are also French, Italian, Spanish, British, Swedish, German, Polish, and so forth. There is plenty of cultural diversity among the native peoples of Europe—different languages, religions, foods, art, traditions, architecture—just as there is plenty of cultural diversity among the native peoples of North America.

Though each Native American group is unique, all are descended from the same stock: people who migrated to the New World from Asia at the end of the Pleistocene epoch. Despite the name commonly applied to the period, “the Ice Age,” the Pleistocene wasn’t just about ice, snow, and cold. Beginning 1.8 million years ago, it was a complex climatic period punctuated by bouts of very cold temperatures with widespread ice coverage, but interspersed by times of ice retreat and temperatures as warm as the present. Paleoclimatologists (the job title for people who study ancient climates) generally believe that the Pleistocene ended about 10,000 years ago. Some suggest that we may still be the Pleistocene—just a quiet, warmer period. How human-induced climate change will affect these natural cycles is anybody’s guess. My advice: Don’t throw away your snow shoes just yet.

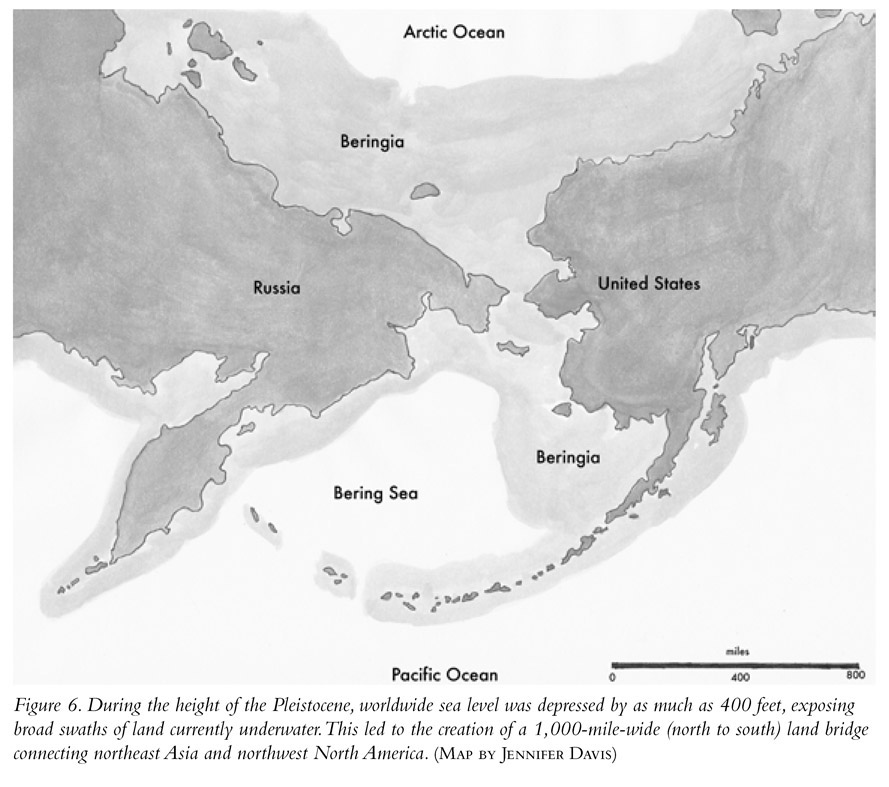

Just as it does today, water during the Pleistocene evaporated from the world’s oceans and fell as frozen precipitation—snow and ice—in cold regions. Unlike the present, however, during cold stages of the Pleistocene that frozen stuff didn’t melt off seasonally. Imagine a really bad winter. Imagine your lawn and the roads on which you regularly commute covered in snow. Imagine that none of it melts in spring or even in summer; it just sticks around, with more ice and more snow being added all the time. Now imagine that happening, almost unabated, for literally thousands of years. (Fun, right? Well, maybe if you’re into skiing or snowmobiling . . .) This process created extensive, mile-high, long-lived bodies of ice called glaciers, especially in northern latitudes and higher elevations (Figure 5). Because that ice didn’t melt and return to the oceans, those oceans became somewhat depleted of water and sea levels dropped worldwide, sometimes dramatically. In fact, during glacial peaks, some lasting for millennia, those levels went down by as much as 400 feet, and broad swaths of land previously underwater became exposed.

One of these newly exposed territories was a very broad “land bridge,” as much as 1,000 miles wide from north to south, connecting the Old and New Worlds between present-day Siberia in northeast Asia and Alaska in northwest North America (Figure 6). That swath of land is called the Bering Land Bridge or just Beringia (named for eighteenth-century Russian explorer Vitus Bering). Bottom line: During peaks of Pleistocene cold cycles, the world was a very different place than it is today.

We know that there were people living in eastern Siberia by about 40,000 years ago. We also know that the period between 40,000 and 12,000 years ago can be characterized as a glacial maximum. That means that soon after people had moved into the far northeastern margins of Asia, the Bering Land Bridge was exposed and likely presented a tempting new territory into which they could expand their population. Merely by following the herds of animals they depended on for food, these Asians slowly entered into what was, truly, a new world. They became the first Americans.

Archaeological evidence shows that the earliest human migration into the New World from the Old occurred certainly more than 13,000 and perhaps as much as 20,000 or possibly even 30,000 years ago (Site 1, Meadowcroft Rockshelter, classified in this book as a First Peoples site). The genetic study of Native Americans conforms very well to the archaeology; they were northeast Asians, and they arrived more than 13,000 years ago.

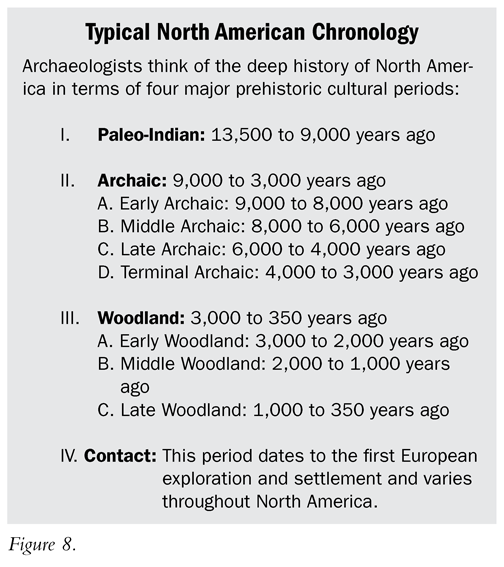

The earliest inhabitants of the New World were drawn here initially as a result of the incredibly rich Ice Age environment that characterized much of the North American continent. Teeming herds of large game animals including bison, woolly mammoth, mastodon, caribou, and horse dominated the landscape and were hunted by the early settlers, who are called Paleo-Indians. The Paleo-Indians lived in relatively small, nomadic hunting bands spread out across the landscape of North America.

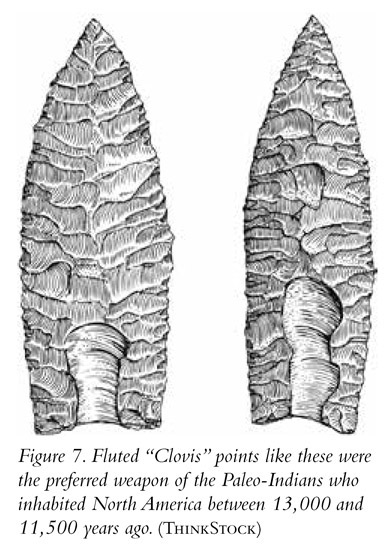

The stone tips of their spears are found in great profusion in virtually every one of our states. These stone points are extremely sharp, finely made, and symmetrical and are manufactured of natural materials including volcanic glass (obsidian) and stones like flint, chalcedony, and jasper. Further, they are characterized by a North American invention—a broad channel called a “flute” (like the concave designs seen on fluted columns) chipped into both faces of the point. Found nowhere else in the world, including the homeland of their Asian ancestors, these flaked channels are presumed to have aided in hafting the stone points onto wooden shafts and, perhaps, in facilitating the flow of blood from the wound of an animal pierced by one of them. The oldest of the fluted points are called Clovis (after a site in New Mexico where they were first found) and date to more than 13,000 years ago. They tend to be long, shaped like a willow leaf, with the flutes traveling from the base to about one-third to one-half their lengths (Figure 7). Clovis points tend to be found in association with the remains of woolly mammoths and mastodons, so it is assumed that these animals were the preferred game of these people. The other type of fluted point is named Folsom (after a site in which they were first found, also in New Mexico). Folsom points are a bit more recent than Clovis, dating to sometime after 11,500 years ago. They tend to be shorter than Clovis, and their flutes travel nearly the entire length of both faces. Folsom points tend to be found in association with the remains of bison rather than extinct elephants. Folsom points likely were made by the descendants of those who made Clovis and reflect a change in the animals the people hunted.

When the Pleistocene drew to a close around 10,000 years ago, many of the animals on which the Paleo-Indians relied for their subsistence became extinct. You already knew that; I mean, when’s the last time you saw a woolly mammoth or mastodon walking around? You might be surprised to learn that horses also became extinct in North America at the end of the Pleistocene. Remember the discussion of Native American cultural stereotypes in the introduction? Not all American Indians were equestrians, but some certainly were. That wasn’t the case, however, until Spanish explorers reintroduced horses to the continent in the sixteenth century. Some of those animals escaped into the wild and became feral, and Native Americans captured them and began using them for transportation. Some native artists produced pictographs and petroglyphs of people riding on horseback. These depictions always postdate the arrival of Europeans in the New World in the sixteenth century. We’ll see some examples in our travels; for example, Site 24, Canyon de Chelly; Site 37, Crow Canyon; Site 41, Newspaper Rock State Historic Monument.

Upon the extinction of so many of the animal species on which they relied, the native peoples of North America had little choice but to adjust and change the focus of their subsistence. For example, when temperatures increased in the Northeast, the then-resident caribou moved north and became locally extinct. People who had traditionally hunted caribou needed to change their diets. Luckily, as the climate warmed, vegetation changed from the treeless tundra in which caribou thrive to, first, a coniferous forest and then, by about 8,000 years ago, a mixed deciduous forest much like the modern one, filled with oak, maple, hickory, and walnut. That forest supported large numbers of deer, and people began relying on this species for meat and hides. The human re-adaptation to the changing climate of post-Pleistocene America characterizes the cultural period following the Paleo-Indian, which archaeologists call the Archaic. The hallmark of the Archaic period is, in fact, the great diversity of cultural adaptations that evolved as groups living across North America adjusted to the newly established, post-Pleistocene environments (Figure 8).

The first peoples of the New World were the ancestors of the folks encountered by European visitors, explorers, and settlers, beginning with the Norse incursion about 1,000 years ago and again after the voyages of Christopher Columbus a little more than 500 years ago. The diversity of their adaptations and their ability to adjust their strategies for survival to the conditions presented in every imaginable habitat with which they were confronted in the New World is a testament to the genius of the first peoples of the Americas. These diverse cultures produced the diverse sites that are the focus of this book.

As they moved south from their entry point in Alaska at the end of the Pleistocene, some of the descendants of the first settlers of America eventually arrived in the regions we now know as the American Southeast and Midwest. As the Pleistocene waned, some of these newly settled areas became characterized by thick, broad, resource-rich woodlands filled with an abundance of wild foods including many species of animals, especially deer, as well as edible seeds, nuts, berries, and roots. These wild crops were so abundant that, even without agriculture, there was plenty of food available and the human population increased. In some places the Archaic people didn’t need to move around a lot to find resources, and with adequate planning and food storage, local villages could be inhabited year-round. This abundance of food and the near-permanence of villages allowed plenty of free time for people to engage in activities beyond what was necessary to put food on their tables. That kind of stability and habitat richness allowed for additional population growth.

Large rivers, among them waterways we now call the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi Rivers, provided natural, navigable avenues for the movement of people and raw materials, as well as finished goods. Trade flourished, and even raw materials available only from a great distance away—for example, shell from the Gulf Coast or copper from Michigan—moved along those rivers to the residents of present-day Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, and the rest of the Midwest and Southeast, who then used them to produce beautiful and impressive works of art.

In some particularly ecologically privileged locations, local population size increased dramatically and there was an uptick in what anthropologists call social complexity. With an increase in population came the need to coordinate and organize the lives of people living in increasingly dense, permanent settlements. Some people—perhaps folks who were already perceived as having powerful connections to the spirit world—became political decision makers and social leaders. Having authority over others, wealth appears to have become concentrated in their hands. Their houses grew larger, and they were able to monopolize rare, valuable, and sought-after raw materials. Their increasing wealth and social status was accompanied by the ability of these powerful people to command the labor of their followers. This is exactly what we see in the archaeological records of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus River Valley, and elsewhere.

In America we see the results of that developing power in the construction of monumentally scaled earthworks. For example, beginning more than 5,000 years ago at a place called Watson Brake in Louisiana (unfortunately this site won’t be among the fifty I discuss here as it is not, as of this writing, open to the public), the native peoples of the New World began moving around large quantities of dirt, using it as a construction material to produce impressive mounds. Over the next 4,700 years or so, virtually right up until, and in some places past, the point of European exploration and colonization of the New World, various Native American societies developed and practiced their own mound-building traditions. We’ll see several of those mounds in our travels.

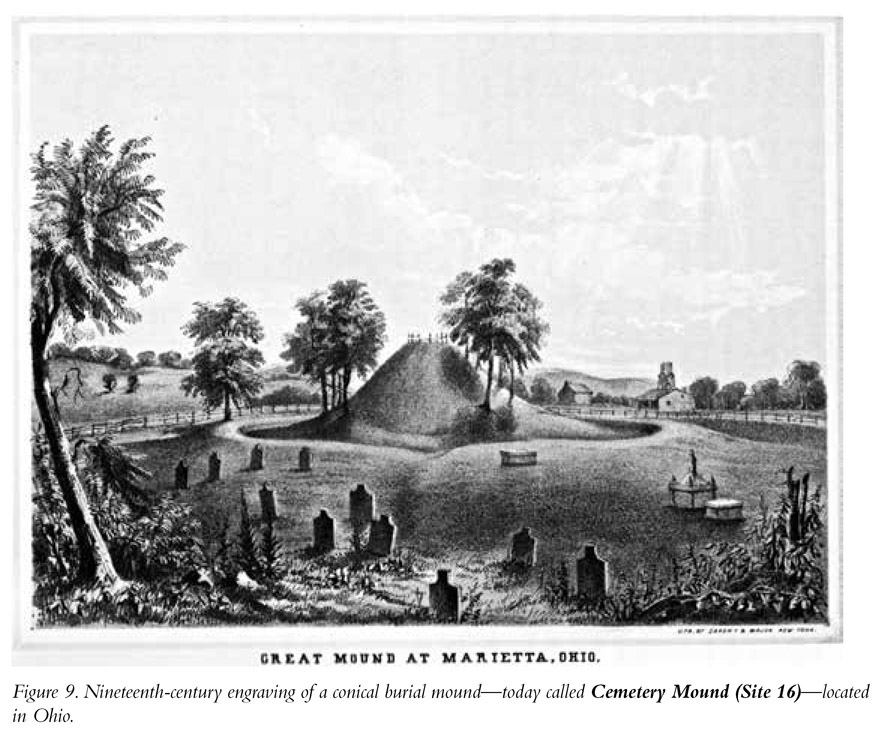

In some cases, the burials of the evolving class of rulers grew in size and complexity as well. Large earth mounds began to mark the tombs of this emerging elite class. As did the pyramids of ancient Egypt, these burial mounds represent tangible symbols of the growing power and importance of the leaders of their societies, even in death. The burial mounds and the beautifully crafted works of art often found interred with the dead are the most obvious archaeological manifestations of the mound-building cultures called Adena, beginning about 2,800 years ago, and Hopewell, beginning about 2,200 years ago, and are among the coolest things we will see in our archaeological odyssey (Figure 9). Adena and Hopewell differ in some of the particulars of their artifact styles. Where the geographic extent of Adena is confined mostly to Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and West Virginia, Hopewell culture sites are found far more broadly, with their mounds and artifacts spread across the entire American Midwest. In terms of art, mound construction, trade, geographical extent, and reliance on agriculture, Hopewell is more elaborate and impressive than Adena. Most archaeologists view Adena at least in part as a precursor to Hopewell.

What happened next, beginning about 2,000 years ago, was a real game changer. There was a revolution in subsistence that resulted from two parallel processes. First, in an attempt to increase productivity and food yield of the wild crops on which they depended, local people in the Midwest and Southeast began tending those plants by preparing seed beds in spring; caring for seedlings; and weeding, watering, and protecting plants from marauding animals. By encouraging the growth of individual plants that, for example, sprouted first, grew most quickly, and produced the largest edible seeds or fruits, Native Americans initiated their own agricultural revolution through the process known as “artificial selection.” These plants included well-known crops like the sunflower and lesser known ones like lamb’s-quarters and pigweed. Agriculture increased the overall productivity of the region and allowed for the development of even larger human populations with even greater density. Agriculture was more efficient than foraging, and fewer people were needed to engage directly in subsistence pursuits. This freed up the time of increasing numbers to do other things: engage in trade, participate in warfare, produce artworks, and build even more monumentally scaled earthworks.

The second process resulted from a quantum leap in agricultural efficiency, made possible by the introduction of a crop that continues to be one of our planet’s most significant food sources: maize. Today the world’s farmers grow more maize than they do wheat, rice, or potatoes. Originating in Central America more than 5,000 years ago, maize—known by most people as corn—entered into what is now the American Southwest by about 3,200 years ago and then the Midwest by about 1,700 years ago.

Maize is a crop rich in nutrients, including many of the amino acids necessary for life. Add beans and squash to maize and you have what some native groups called “the three sisters.” The combination of these three crops was important for a healthy diet because beans and squash provide the amino acids that are missing in corn. A diet including all three crops provides a complete protein in a nonanimal package. Brilliant! Beyond this, maize is a hardy, resilient crop with very high yield potential, and it is genetically malleable. Varieties of corn can be grown across an enormous range of habitats. Maize’s origins are in the tropics, but varieties can be grown successfully today as far north as Canada.

Especially after the movement of corn into North America, some societies experienced a great leap in their ability to feed more mouths on less acreage. At that point we see in the archaeological record evidence of increasing sedentism, villages of greater size, and a ramping up of social and economic inequality. In other words, some people became rich and power became concentrated in their hands, other people were poor, and some fell in the middle. In the maize-growing cultures that developed in the rich bottomlands of major river valleys in the American Midwest and mid-South, America saw the development of class societies, with the rich and powerful at the top and regular working people at the bottom. In this culture, now called Mississippian, most of the regular folks were farmers who were able to produce far more food than they needed to feed themselves and their families. Their agricultural surplus provided the food necessary to support the ruling group as well as classes of people who did not farm but might be specialists in artistic pursuits, including ceramics, the manufacture of stone tools, crafting works in shell, fabric production, and metallurgy.

Though they still constructed burial mounds for the interments of their leaders, with the support of rising populations and with increasing power and wealth concentrated in the hands of those few leaders, earthworks became even more monumental. Some were elevated platforms, on top of which were constructed the homes of the rulers of these societies. The elevated status of the leaders of these groups was symbolized by the elevated context of their homes on the tops of artificial, symmetrical mountains of earth, the platform mounds.

In most cases, individual mounds or clusters of such earthworks marked the locations of ceremonial or religious centers, with small resident populations of the ruling and priestly classes. A broad and dispersed series of hamlets and villages surrounded these ceremonial centers, where farmers lived, grew food, and gave their allegiance to and provided material support for the leaders and craftspeople living in them. In return they received the benefits of being members of a chiefdom or kingdom: military protection, perhaps an infrastructure that included roads, the protected movement of goods, and probably the promise of a place in the afterlife. In a few instances, Site 9, Cahokia is the clearest example, ceremonial centers evolved into population centers of a truly urban character. Cahokia was a Native American city with a large resident population that dominated a broad expanse of surrounding territories filled with smaller communities. It is about as far removed from the common stereotype of nomadic Indians as you can get. The residents of these communities likely viewed Cahokia as the capital of their nation and those who lived atop the platform mounds located there as their leaders. Cahokia is still an amazing place today, and we will visit it in our odyssey.

The Mound Builder Myth

The mounds, especially the ones I’m including in our fifty-site archaeological odyssey, are hard to miss, but don’t feel bad if you’ve never heard of them. A lot of folks haven’t. In fact, historian Roger Kennedy hadn’t heard of them either. That’s kind of shocking, since from 1979 to 1992 Kennedy was the director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. Yeah, that’s the official, national history museum of the United States. Kennedy was a trained historian, a highly regarded researcher, and a brilliant writer. In an interview conducted in 2009 he admitted that until the 1990s he was wholly unaware of the Native American cultures that constructed a multiplicity of variously configured earth-works in the American Midwest and Southeast.

It’s bad enough that, as I noted earlier, the names given to some ancient Native American sites by European explorers and settlers implied that groups other than Native Americans built them. An even more unfortunate version of this misappropriation of the archaeological record of North America involves an elaborate myth concocted by early European settlers: the existence of an entire lost race of mound builders—a race that bore no connection to American Indians. This mound builder myth claimed that a lost race—maybe they were Europeans, perhaps they were members of the Lost Tribes of Israel, or maybe they were Atlanteans after all—must have constructed the thousands of earthworks distributed across the ancient landscape of North America. The mounds were perceived by at least some of the Europeans who encountered them as being too large and too complex, as well as requiring too much concentrated and coordinated effort, to have been the work of American Indians. We recognize now that this is nonsense—arguably racist nonsense at that. Denying that American Indians could have been responsible for mound construction represents a sad chapter of American history.

Kinds of Mound Builder Sites

The earthworks of the various mound builder cultures are legion and diverse. We can divide the kinds of mounds or earthworks found in North America, examples of which we’ll be visiting in our journey through time, into a number of separate categories:

Burial Mounds

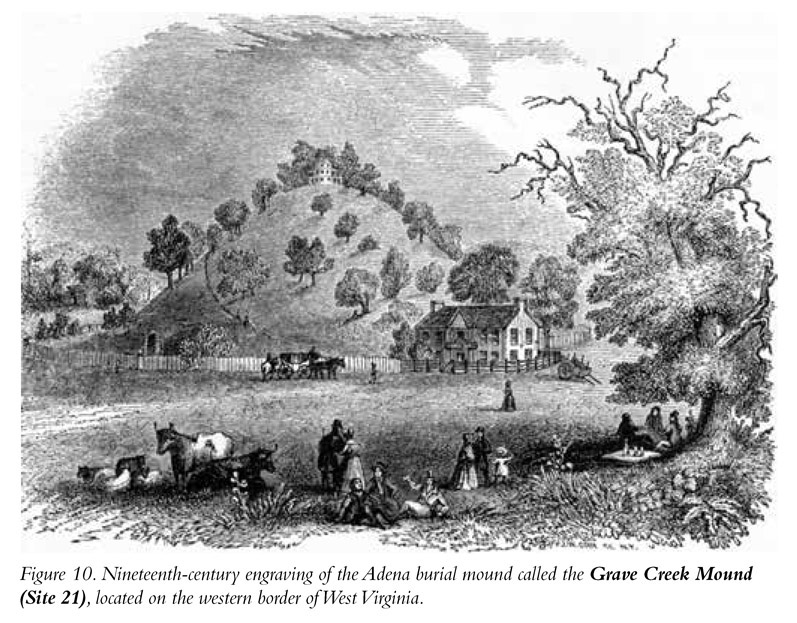

Most American burial mounds are conical piles of earth with circular bases. They often are large—the tallest are nearly 70 feet high—and meticulously symmetrical (Figure 10). In many cases, the tombs of people who likely were of tremendous importance in their societies have been found in the bottoms of these earthworks. Think of these mounds as a Native American version of Egyptian pyramids. They’re generally smaller and built of dirt, not stone, but the fundamental concept is the same—a monumental tomb, the construction of which required the marshaling of significant resources and labor, intended as the final resting place of an important person, perhaps a leader or a priest. Sometimes additional interments were added after the mound was constructed by digging shallow pits into its side and placing the remains of the deceased, sometimes cremated, in the holes. Some large burial mounds aren’t circular but are oval at their base, creating an elongated earthwork with a linear ridge at its apex. These oval mounds usually contain multiple burials, most of which were added after the mound itself was constructed. The Adena and Hopewell cultures mentioned earlier are perhaps best known for their construction of burial mounds (Site 16, Cemetery Mound; Site 17, Miamisburg Mound; Site 18, Mound City, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park; Site 21, Grave Creek Mound).

Enclosure Mounds

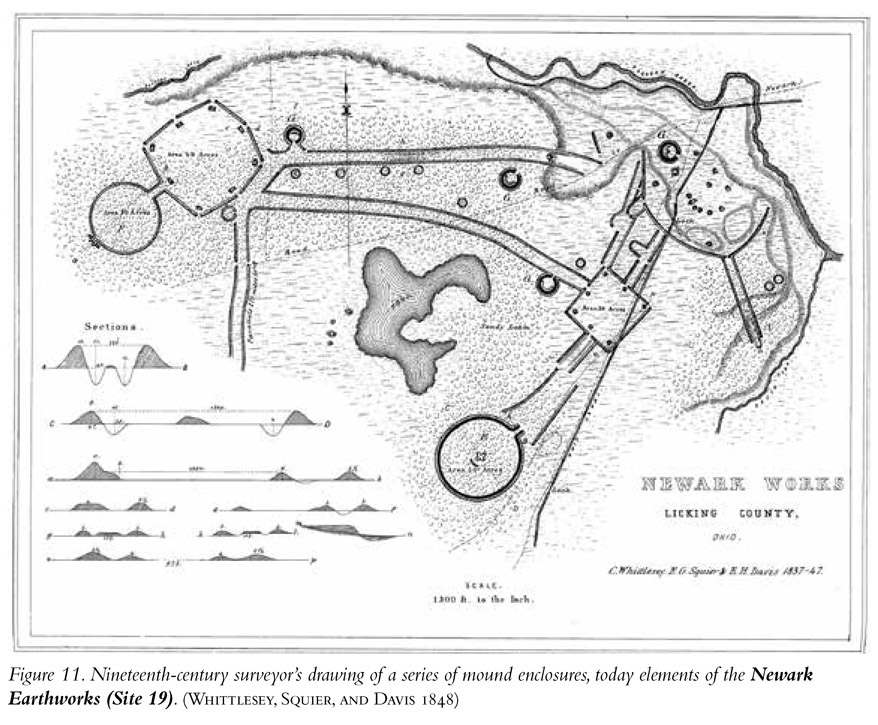

Enclosures are sizable spaces delineated and distinguished from the surrounding landscape by one or more earthworks (Figure 11). The individual earthworks in an enclosure most often are artificial ridges of dirt, generally broader on the bottom and narrower as you approach the top, and may be only a few feet high. A cross section of such a mound is in the shape of a parabola, and they are in essence the equivalent of earth berms or ridges. Some enclosures are circular, circumscribed by a mound built as a large ring. In some examples, four individual linear mounds were built at right angles to one another, intersecting at their ends to create a four-sided enclosure—a square or rectangle. Sometimes the enclosed space presents a more complex geometric shape. One of the mound sites in my list of fifty is composed of a series of discontinuous linear earth-works that, together, delineate and enclose an octagonal space of about 50 acres. Finally, the mounds marking some enclosures are irregular in form, following the edges of a natural, flat-topped hill, for example.

The mound ridges marking the enclosure sites do not appear to have been defensive in nature. They could not have supplied very much practical protection to those within the enclosure from enemies attacking them. It appears that the construction of a mound or mounds to enclose a space was intended to ritually separate an area deemed sacred—the area within the enclosure—from the surrounding territory. This likely was the case in a couple of our fifty sites (Site 18, Mound City, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park and Site 19, Newark Earthworks, both in Ohio).

Effigy Mounds

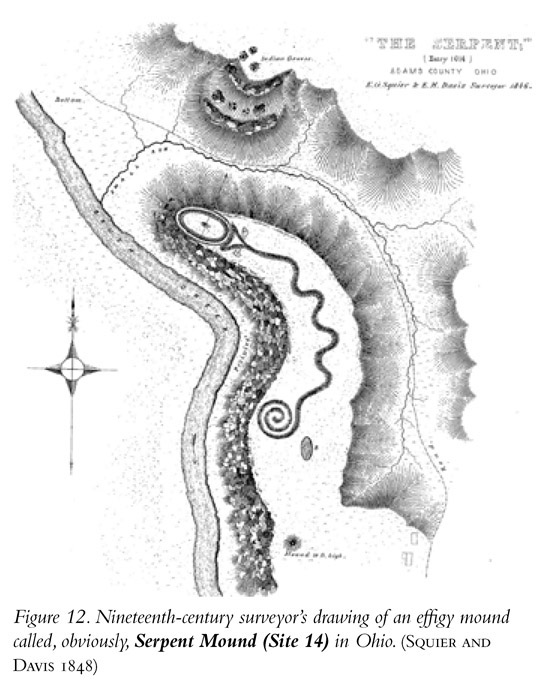

An effigy mound is an often beautiful, sometimes monumental sculpture in which the artist’s medium was earth or stone cobbles (Figure 12). Effigy mounds found in the United States include those in the shape of a coiled snake (Site 14, Serpent Mound in Ohio, certainly my favorite effigy earthwork), marching bears, various other small mammals, reptiles, and flying birds (Site 6, Rock Eagle Effigy Mound). It’s very difficult to suss out the precise meaning of effigy mounds to the people who made them. Are they art, religion, or a bit of both? In any event, whatever they mean, effigy mounds are very cool.

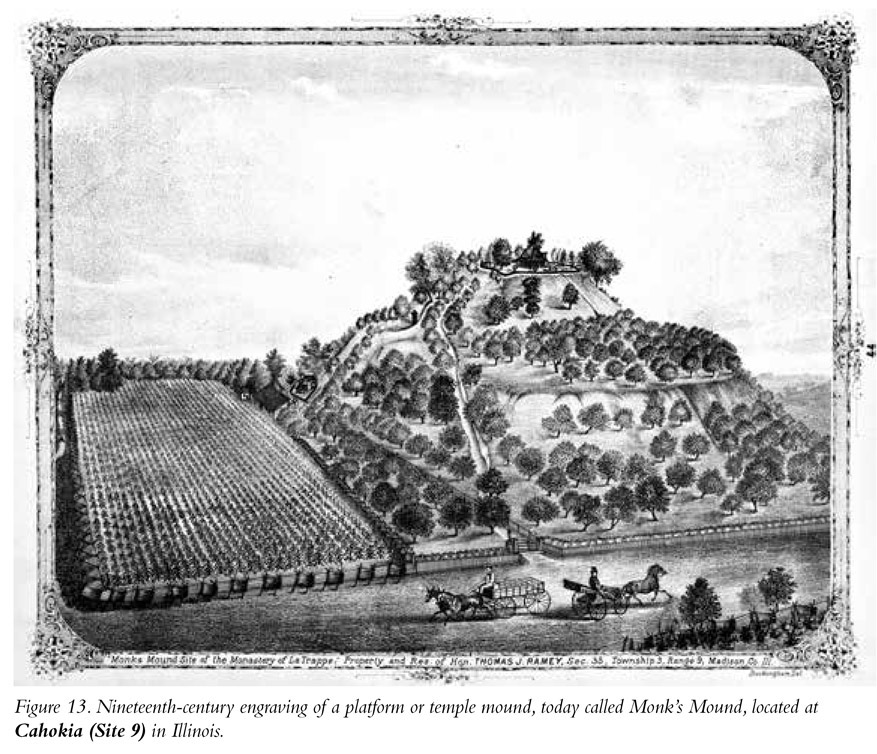

Platform or Temple Mounds

These generally are the largest of the earthworks built by the mound builder cultures. (Figure 13 is a historical engraving depicting Monks Mound at Site 9, Cahokia.) Usually square or rectangular at their base—though they sometimes have a more complex footprint—the sides of these mounds were built at various angles from gentle to steep, sometimes with multiple tiers or levels. Many of the temple mounds are in the shape of truncated pyramids. Imagine a typical Egyptian pyramid with its top one-third to one-half missing, leaving a flat platform at its apex upon which a structure might be built. Each of the four faces of a platform mound, therefore, is in the shape of a trapezoid, not a triangle as in Egyptian pyramids. Archaeologists excavating the tops of platform mounds have often found the remains of often large, elaborate log or wattle and daub structures. Artifacts recovered in the remains of those structures suggest that the buildings atop the mounds were temples or palaces in which the society’s rich and powerful lived. Historical accounts by Spanish explorers in the Southeast and French traders near the mouth of the Mississippi confirm that the ruler of the community, along with the ruler’s family, lived in the buildings atop some of the platform mounds.

The largest of these monuments, Monks Mound, is named for the Trappist monks who lived nearby and farmed one of the terraces of the earth pyramid many years after the Indian site was abandoned. Monks Mound is located at the site today called Cahokia (Site 9), though we have no idea what its residents called their city; it had been abandoned by the time European explorers of the Midwest arrived there. Monks Mound is nearly 100 feet high, its base covers 14 acres, and it contains more than 21 million cubic feet of dirt. That’s a lot of dirt; more to the point, that’s a lot of work undertaken by an enormous number of people whose labor must have been very tightly organized to accomplish the task. The mound builder cultures possessed no beasts of burden; the earthworks were the product entirely of people power. Monks Mound is, by volume, the fifth-largest pyramid in the world. And it’s not in Egypt or Mexico; it’s in Illinois. The other Platform Mound sites included here are Site 2, Moundville Archaeological Park; Site 3, Toltec Mounds; Site 4, Crystal River; Site 5, Kolomoki; Site 7, Etowah; Site 8, Ocmulgee; Site 10, Angel Mounds; Site 13, Town Creek Mound; Site 20, Pinson Mounds; and Site 22, Aztalan Mounds.

Village Sites

Some of the mound sites we will visit in this book, especially those with platform mounds, were villages, some with substantial populations. But there also are thousands of communities spread across the Midwest and Southeast where there are no platform, burial, or enclosure mounds, and therefore little to see beyond a modern, agricultural landscape. One wonderful exception to this is included in my fifty-site odyssey: Site 15, SunWatch Indian Village in Ohio. Though there are no earthworks there, replicas of the houses at SunWatch have been built directly in the footprints of their archaeological remains, providing a unique perspective of life among the ancient people of the Midwest. The other Platform Mound sites also were occupied villages, but I am including only a couple of other sites in the “village” category—Site 11, Poverty Point in Louisiana and Site 12, Grand Village of the Natchez in Mississippi—where there are mounds, but the primary reason for visiting them is the extensive village located at each.

Many mound sites can still be visited today. They’re not hidden, but often preserved and celebrated as historic landmarks, national monuments, and state parks. They are impressive and truly monumental, representing an important part of American history. Sadly though, not many people know about these places. Equally sadly, not enough people visit them to witness firsthand the amazing achievements of America’s first inhabitants.

We now travel west, where many people are at least passingly familiar with two of the modern Native American tribes living in the American Southwest: the Navajo and the Hopi. With a population of more than 300,000, the Navajo are, depending on the details of how a tribe defines its membership, either the first or second most populous tribe in the United States. The Cherokee are the other group in the top two in population size.

The modern Hopi and their close relatives (including the Zuni, Jemez, Tanoan, and other people living in communities in Arizona and New Mexico) are included in a more broadly defined group, the Pueblo Indians. The “Pueblo” name was conferred on them by Spanish explorers in the sixteenth century. Pueblo is Spanish for “town.” Those explorers were struck by the beauty of the villages of the native peoples they encountered, consisting of finely made, multistory, adobe apartment complexes. While the Pueblo or Puebloan people have a much smaller population (estimated to be about 35,000), their roots in the American Southwest are far deeper than those of the Navajo.

In a sense, the modern Pueblo people can be at least indirectly traced to the first human settlers of the Southwest, who arrived more than 13,000 years ago. Based on archaeology, history, language, and genetics, the ancestors of the modern Navajo moved into the Southwest from the north only about 700 years ago. Most of the village sites presented in this book that are located in the American Southwest—including those exhibiting cliff dwellings (Site 23, Montezuma Castle; Site 24, Canyon de Chelly; Site 26, Walnut Canyon; Site 28, Betatakin; Site 29, Mesa Verde); great houses (Site 24, Canyon de Chelly; Site 25, Casa Grande; Site 27, Wupatki; Site 30, Aztec; Site 31, Chaco Canyon); and stone towers (Site 32, Hovenweep)—were the work of the direct and indirect ancestors of the modern Pueblo people.

Cultural Streams of the Ancient Southwest

Based on the diversity exhibited at sites in the Southwest, archaeologists have divided up ancient cultural groups there; those divisions are often largely based on pretty technical considerations. It’s complicated. Certainly we see fundamental commonalities among the ancient peoples spread across the Southwest; for example, their construction of buildings using adobe and stone and their reliance on corn, beans, and squash in their diets. But we also see in the archaeology of the region that folks in different areas made different styles of pottery, employed different types of masonry in their architecture, and had somewhat differing diets. Are those differences sufficient to call them different cultures? Would they have defined themselves as different peoples? Unfortunately we can’t go back in time and ask people living in different regions if they view the folks living on the other mesa, or on the other side of the mountain, river, or desert, as members of their group or as foreigners, as friends or as enemies. We can’t even be certain they spoke the same language or spoke mutually intelligible dialects of the same language.

There’s plenty of diversity in the cultural practices and beliefs of the modern Pueblo people who live in their twenty-one existing communities—the “pueblos” mentioned by sixteenth-century Spanish explorers. For example, some modern Pueblo groups trace their ancestry exclusively through the female line. If you’re a kid, you belong to your mother’s lineage, not your father’s. But other Pueblo people trace their family ties through their fathers. You belong to your father’s family and are not a member of your mother’s. For a cultural anthropologist, that’s a pretty big deal and an important difference.

The spoken language of the Pueblo people varies from place to place, but most—for example, among the various Hopi groups—speak dialects of the same language. Some modern Pueblo people, however (for example, the Zuni), speak a language unintelligible to other Puebloans. Again, that’s a pretty significant difference.

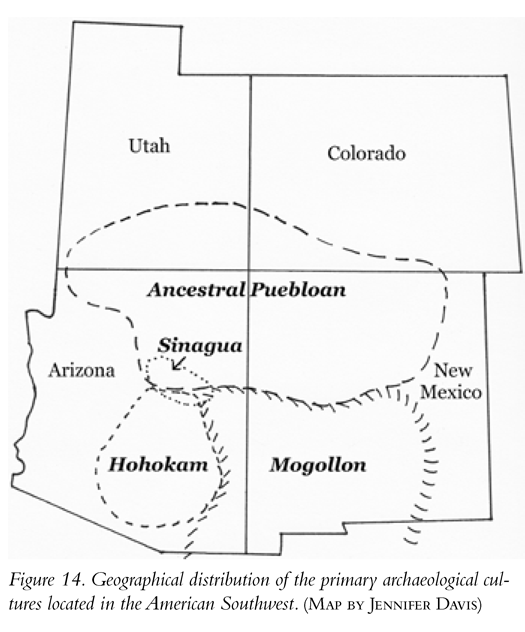

With all that diversity among living people, it’s not surprising that we see plenty of diversity in the archaeological record of the ancestors of those folks. Archaeologists have identified and defined a number of different “cultural streams” leading to the modern Pueblo cultures of the Southwest. These streams include Mogollon, Sinagua, Hohokam, and Ancestral Puebloan (Figure 14).

Each of these named archaeological cultures exhibited somewhat differing practices and lived in the shapes, colors, and styles of the pottery they made are recognizably different. Their houses—in terms of size, the specifics of the masonry, their overall appearance, and even details of their entry doors—vary. The ways in which they memorialized and interred their dead, again, are different. The foods they emphasized in their diets and their reliance on rainfall or irrigation in support of their agriculture also differ across time and space. But in the end, it should be emphasized that the people who made the great houses and cliff dwellings and who produced many of the art sites we will be visiting across the face of the American Southwest were closely related, sharing far more in common than what distinguished them. Let me describe the most commonly identified archaeological cultures of the American Southwest.

Mogollon

Briefly, Mogollon refers to sites located primarily in the southern reaches of New Mexico, southern and eastern Arizona, and northern Mexico. The name comes from the Mogollon Mountains that are in the core of this group’s geographic range. Those mountains were named for an eighteenth-century Spanish governor of New Spain.

Like all native peoples of the Southwest, early in their history the Mogollon were foragers of wild plants and animals, but by about AD 650 the Mogollon embraced farming as their primary mode of subsistence, focusing on the iconic Native American triumvirate of corn (maize), beans, and squash. Originally building and living in semi-subterranean “pit-houses,” Mogollon people began constructing aboveground pueblos by about AD 1000 and cliff dwellings a couple hundred years later.

Perhaps the most distinctive of the Mogollon subgroups were the Mimbres people, best known for their singular and stunning ceramics with white backgrounds and festooned with striking, jet black depictions of animals, fish, and insects in a sharply geometric style. It’s unique and incredibly cool stuff. And my one tattoo, a lizard, is based on a Mimbres motif. The rock art we’ll see at Site 38, Three Rivers Petroglyph Site was produced by Mogollon people and reflects the overall look of Mimbres art.

Hohokam

Sites bearing the specific characteristics labeled Hohokam are found in southern and central Arizona; the modern city of Phoenix sits in about the middle of Hohokam territory. Hohokam is a Pima Indian word for “the people living in the Sonoran Desert.” Flourishing between AD 1 and AD 1500, the Hohokam left behind a large number of sites signifying an extensive population with substantial “great houses,” large, free-standing adobe apartment houses, like those at Site 25, Casa Grande. The Hohokam are distinguished as the ancient American Southwest culture most reliant on and successful at the construction of irrigation canals for farming—which, like the Mogollon, was based on the cultivation of corn, beans, and squash. The extensive network of well-engineered canals, which must have required a tremendous amount of coordinated labor, is the hallmark of the Hohokam.

Sinagua

Sinagua is Spanish for “without water.” Sites designated as Sinagua are located in central and northern Arizona, ensconced in a small pocket north of the core area of the Hohokam. Sinagua sites are distinguished from the other defined archaeological cultures of the Southwest primarily on the basis of their pottery styles. We will visit the remnants of a number of their villages, including Site 23, Montezuma Castle; Site 25, Walnut Canyon; and Site 27, Wupatki. Some researchers actually include the Sinagua sites under the heading of Ancestral Puebloan; they are really quite similar.

Ancestral Puebloan

Ancestral Puebloan refers to sites located primarily around the Four Corners region, called that because four states—Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado—meet there at right angles. It is fair to say that the construction both of great houses and cliff dwellings reached its zenith, in terms of both size and elaboration, among the people we now call Ancestral Puebloan. Among the Ancestral Puebloan sites listed in my fifty are Site 28, Betatakin; Site 29, Mesa Verde; Site 30, Aztec; Site 31, Chaco Canyon; and Site 32, Hovenweep, as well as the cliff dwellings and great houses located in Site 24, Canyon de Chelly (the art we will visit there is mostly Navajo).

By the way, “Ancestral Puebloan” has in the past been called “Anasazi,” and many authors still use that name. The problem with Anasazi is that the word originated, not among the modern descendants of the people who actually built and lived in the sites we label with that term, but in the Navajo language. The meaning of Anasazi makes its use even more problematic. When European settlers of the American Southwest asked the Navajo about the identity of the builders of the abandoned cliff dwellings and great houses that abounded in the region, the Navajo referred to those builders as ana’ai (which means “alien,” “enemy,” or “foreigner”) and sazi (which refers to a body that has entirely decomposed). In other words, the Navajo labeled the people who built the sites as, essentially, “People who weren’t Navajos and whose bodies have decayed to dust.” You can imagine that this Navajo term is not favored by the Pueblo people.

Ultimately, from your perspective as a time traveler, mastering the technical differences among the named archaeological cultures in the Southwest is not crucial; anyway, the names we impose on them today bear little relationship to what those people called themselves. Don’t worry; I promise there won’t be a test. What is important is our understanding that the spectacular sites we will visit all reflect the genius of Native America. In all of them we see evidence of their clear ability to carve out a life in a hot, dry environment that often presented very challenging and difficult conditions for agriculture. Their architecture was impressive, sophisticated, and beautiful and reflects the great skill of their masons. There is evidence that they were careful observers of the night sky and preserved their observations in art. They built a vast system of roads and participated in a far-flung network of trade and social interaction.

However you divide up their cultures, the agriculture, architecture, astronomical knowledge, trading networks, art, and technology of the ancestors of the various groups and subgroups of the modern Pueblo and Navajo people are amazing and impressive. And what’s great about it all is that you can visit and personally experience places that reflect that genius.

How old is art? For how long have we human beings been depicting the real world around us, the visions seen in our dreams or in a trance, or simply the shapes and forms that inhabit our imaginations?

If you’ve ever taken an art history course in high school or college, you’ve almost certainly seen ancient depictions that are usually called the “first art.” These would be the cave paintings of the European Upper Paleolithic dating to as much as 35,000 years ago. Indeed, the paintings our ancient human ancestors rendered on the walls of caves like Chauvet, Lascaux, and Altamira of animals including horse, rhinoceros, woolly mammoth, and elk are remarkable. But, it turns out, the magnificent tableaux produced by these Ice Age Europeans were not necessarily the earliest art. Archaeologists have now traced back equally old art to caves in Indonesia, where ancient people produced naturalistic paintings of local animals and even left imprints of their hands, the equivalent of an early signature and message: “We were here!” Even older abstract scribbles and doodles—incised lines in pieces of ochre, a soft mineral—have been found in southern Africa dating to more than 70,000 years ago. Other objects representing what amount to “paint pots” have been found in South Africa as well, and date to more than 100,000 years ago. Even more remarkable, a recent reanalysis of a shell dating to more than 1 million years ago on the island of Java revealed the presence of a series of engraved lines produced by a human ancestor with a brain capacity only about two-thirds that of a modern human being.

This astonishing evidence implies that art, however we define it, has extremely deep roots in the human lineage. It might even be argued that art isn’t just something human beings do because we are capable of it; maybe the artistic representation of things we have seen, thought, and imagined is an imperative, something we need to do. Think about that when you consider all of those finger paintings, watercolor masterpieces, and pen-and-ink drawings that end up hung from magnets on refrigerators all across America. It’s not just cute; it’s a reflection of how modern human children are part of a continuum of the artistry that has defined our species.

The art you will see in our fifty-site journey represents a remarkable place on that continuum. Here you will see petroglyphs, images etched, incised, scratched, or pecked into rock faces by breaking through an external, often dark patina, and exposing the lighter rock beneath to produce an image. You will also see pictographs, images produced by the application of paint onto a rock surface. Occasionally the ancient artists of America combined those two techniques in the same art panel, adding flourishes of pigment to the incised image. Finally we’ll visit a couple examples of geoglyphs, the manipulation of material on the ground—for example, by the arrangement of stones into a pattern—often on a monumental scale, to produce an image comprehensible only from above.

Styles of Rock Art

If you think back on your art history class, you’ll probably remember (if only vaguely) a great profusion of artistic styles, schools, and movements that varied across time and space. There’s realism, surrealism, impressionism, post-impressionism, romanticism, cubism, op-art, and on and on. Well, just as there is tremendous diversity of themes, styles, and approaches in the Western art tradition, so is there tremendous diversity in the art of Native America. If you are interested in an extremely detailed analysis of the many styles of rock art in the American Southwest, there is no better book to read than Polly Schaafsma’s Indian Rock Art of the Southwest. For our purposes, I am going to list and describe some of the art styles we will most commonly encounter in our odyssey. Many of our fifty sites exhibit more than one art style, but I’ll list some of the sites where each style is most common.

Fremont

Many of the Southwest rock art sites we’ll see reflect a style of art called Fremont, named for the archaeological culture first defined from sites located along the Fremont River in north-central Utah where much of the style is concentrated. The Fremont people practiced a mixed economy—planting corn, beans, and squash and also hunting wild animals and gathering wild plants. Their sites generally date between 2,000 and 700 years ago. Fremont art is distinctive and recognizable. The most common animal depicted is the bighorn sheep. Fremont art also includes representations of deer, dogs, birds, lizards, snakes, spirals, human handprints, and anthropomorphs: images of humanlike beings standing on two legs. Fremont anthropomorphs usually have very broad shoulders, and their bodies taper to narrow waists; their body shapes are usually described as trapezoidal. In some versions the anthropomorphs lack arms or legs. Many Fremont anthropomorphs are wearing elaborate headdresses. Some of the slickest Fremont art we’ll see is found at Site 39, San Juan River; Site 44, Nine Mile Canyon; Site 46, McConkie Ranch; and McKee Springs in Site 47, Dinosaur National Monument.

How old is the Fremont art? Rock art can be pretty hard to date directly. Radiocarbon dating works on things that were alive, not on rock. However, there is a radiocarbon date indirectly associated with Fremont art. The Pilling Figurines—eleven small sculptures found in Utah—in three dimensions bear a striking resemblance to the two-dimensional Fremont anthropomorph petroglyphs. Burned wood found at the same site has been dated to about 1,000 years ago. This date provides a good estimate for the age of at least some of the Fremont-style petroglyphs.

Jornada

All the Jornada style rock art in this book is found on black basalt boulders (basalt is a volcanic rock). The look is hard to define, but it’s unique and recognizable. There are lots and lots of animals, including big-horn sheep, birds, fish, snakes, and insects. The bodies of the critters often are filled with intricate geometric designs. Jornada also features masks, rainbows, “cloud terraces” (square-stepped images), and mythical beings. The archetype of Jornada style rock art is found at Site 38, Three Rivers Petroglyph Site in southern New Mexico. The habitation site adjacent to the rocky crest where the art can be seen is dated to between AD 1000 and AD 1400, and that’s a pretty good estimate for the age of the style. You’ll also find lots of Jornada art at Site 36, Petroglyph National Monument, also in New Mexico.

Barrier Canyon

The Barrier Canyon style is characterized by extremely spooky pictographs of anthropomorphs. The images tend to be elongated; they look like human beings—well, spirit beings that look sort of human—that have been stretched. The stretchy thing is interesting, as after ingesting hallucinogens, fasting, or as a result of sleep deprivation, human beings often experience hallucinations in which everything seems to elongate. Perhaps such hallucinations were the inspiration for the Barrier Canyon art style. Barrier Canyon figures also tend to have very large, googly eyes and often lack arms or legs. The most recent dating of Barrier Canyon art places it in the range of 1,000 to 2,000 years ago. Site 40, Horseshoe Canyon (which used to be called Barrier Canyon, providing the name for the style) is the defining site. You’ll also see Barrier Canyon pictographs at Site 42, Buckhorn Wash; Courthouse Wash in Site 43, Moab; and Site 45, Sego Canyon.

Coso

The art of the Coso Range in Southern California exhibits some stylistic similarities with what is called Interior Line Style art (seen at Site 50, Dinwoody in Wyoming). As in many of these art traditions, there are lots of animal depictions, many of which are bighorn sheep. There are also plenty of prong-horn antelope and deer, as well as lots of strange and otherwise uninterpretable geometric patterns etched into the rock. Coso art is also characterized by fantastical anthropomorphs and what appear to be pouches or bags that have been identified as “medicine bags,” in which people would hold charms that were deemed to confer good luck and success on the bearer. The best place to see Coso art is at Site 34, Little Petroglyph Canyon in Southern California.

Dinwoody

The Dinwoody style characterizes a number of sites in the northern Great Plains and is actually a subset of a style called Interior Line Style. This tradition includes lots of anthropomorphs with rectangular bodies and large heads. There also are images of birds, and some of the anthropomorphs appear to have birdlike features, including wings. The more characteristic element of Interior Line Style rock art is the detailed, almost busy elements incised into the bodies of the depicted creatures. There are lots of straight and wavy lines, circles, and dots. Site 50, Dinwoody Lake in Wyoming is the source of the name of the style.

Northwest Coast

The art style of the Indians of the Northwest Coast in Oregon, Washington, western Canada, and Alaska is exemplified by their totem poles. It’s a beautiful, recognizable, and unique style, with depictions of such animals as owls, beavers, wildcats, and whales. The rock art of the northwestern United States can be characterized as essentially a two-dimensional version of the art style of totem poles. The rock art at Site 48, Horsethief Lake in Washington’s Columbia Hills State Park is a perfect example of this style.

Historic

The creation of rock art continued into the period of European migration to the New World. Perhaps the most obvious indicator of this is the themes and elements seen in the art. For example, depictions of horses, especially horses ridden by men holding guns, date to this historic period. Similarly, rock art showing cows, steam locomotives, and typical Euro-American houses reflect the native reaction to the presence of these new elements in their environment. Site 37, Crow Canyon in northern New Mexico, viewed by the Navajo as the place where they were created, has wonderful examples of their tribal rock art. Site 41, Newspaper Rock was used as a canvas for petroglyphs for centuries, if not millennia; there are some Fremont-looking bighorn sheep, but there also are some obviously recent historical markings of people on horseback. Similarly, the pictographs of Site 24, Canyon de Chelly, including local animals (the paintings of Antelope House), and the amazing painting on the rock wall near Standing Cow Ruin that shows a procession of men riding on horseback, holding guns, and surrounding a horseback rider wearing a cape exhibiting a Christian cross represent what is effectively a historical document of Navajo interaction with the Spanish invaders of their canyon. Also, the rock painting at Site 35, Chumash Painted Cave appears to be of recent historical vintage, perhaps no more than about 500 years old. The geoglyphs found at Site 33, The Blythe Intaglios may be associated with historical tribes in Southern California, and Site 49, The Bighorn Medicine Wheel also appears to be less than 1,000 years old.

Explaining the Art

Maybe one of the essential elements of art is that there is no single explanation for it. Is the rock art seen in our fifty-site jaunt through time religiously motivated? Some of it likely was. How else to explain the images of spirit beings at the Great Gallery in Site 40, Horseshoe Canyon? Was it intended as history? Is the Great Hunt Panel at Site 44, Nine Mile Canyon a record documenting a particularly successful hunt of bighorn sheep? Was it intended to entertain, even to make people laugh? I certainly laughed when I saw the depiction of the flute-playing sheep at Sand Island, included here as part of Site 39, San Juan River in Bluff, Utah. And why, oh why, do so many of the males depicted in rock art have gigantically long penises? And how will you explain those to your 4-year-old? I’m sorry; you’re on your own there.

I am not going to attempt to explain the art here. Especially as a non-Native person, I feel uncomfortable imposing a view about the meaning of art that is steeped in the perspective of Western art traditions. But I will say this: The rock art you will see is amazing. It’s beautiful, intriguing, astonishing, confounding, moving, and thought-provoking—in other words, it is art. And that explanation is more than enough.

Alright. We have now reached a point where it’s time to move on, literally and figuratively, and begin our trek through time.