Hopewell Culture National Historical Park • Chillicothe, Ohio

Journal Entry

April 21, 2009

Mound City is effectively a “necropolis”—a city of the dead. The site consists of not just one burial mound but twenty-three (there may have been more); the cluster of mounds is enclosed in a square earthen enclosure. Human remains are contained in each of the mounds. The site was used as a burial ground between 200 BC and AD 500, and interments of the most important people contained elaborate arrays of grave goods, including sheets of mica, copper sculptures, and smoking pipes made to resemble local animals. The age of the site and the nature of the artifacts found there place it firmly within the Hopewell Culture. Administered by the federal government, Mound City is one of five separate and significant mound sites that together make up Hopewell Culture National Historical Park.

Before my Spring 2009 visit, I had been to Mound City back in the early 1980s. One of the significant differences between what the site looked like in the two visits relates to one of the burial mounds. Back in the 1980s there was a trail leading into the site, up to and then into one of the mounds; you actually could walk into the ancient tomb. Inside, the human burial had been left intact and in place. The original log tomb had been reconstructed, so the grave itself was in an open space covered by the soil of the mound. There was a human skeleton along with grave offerings, if I recall correctly, which gave the viewer the opportunity to see the interment much as it looked when the deceased had been laid to rest likely about 2,000 years ago. I’m pretty sure there was a Plexiglas wall that prevented visitors from actually walking into the grave itself.

Certainly that was a remarkable scene, and similar open burials, consisting of human remains and accompanying artifacts that had been placed in the interment, could be found at a number of sites in the Midwest. I admit to very much appreciating at the time being able to see the intact burial, but I recognize that treating human remains as though they were little more than artifacts in a museum exhibit was troubling and more than a little inconsiderate of the feelings of the descendants of the deceased. After all, how would most Americans feel if you could walk into the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery and snap selfies with the dead soldier to post to your Facebook page? Not so great, right? Taking into consideration the sensibilities of Native Americans and others, the federal government closed off the open burial at Mound City.

What You Will See

Mound City is an enormously impressive cluster of burial mounds surrounded by an earth berm about 4 feet high that encloses the approximately 13-acre necropolis (Figure 47). The entire site has been reconstructed. It was more or less decimated by construction of a military encampment during World War I, but today its overall look is very impressive and, with the aid of very precise nineteenth-century maps, an accurate representation of what the site looked like aboriginally. You certainly should take a walk around the grounds of the necropolis for a personal perspective of the incredible amount of labor that went into simply constructing the mounds themselves. Most are conical, with the largest originally being about 19 feet high and 90 feet in diameter at its base. There is one larger mound with an elongated, elliptical footprint; it contains multiple burials.

The burial practices at Mound City involved a number of steps. First, a shallow basin was dug or, in some cases, a low earth platform constructed. The body of the deceased was placed in the basin or on the platform and a log structure, essentially a charnel house, was constructed around the body. Next the building was set ablaze and the body cremated. The ashes and remaining bones were piled up and then important objects were placed around the remains—art works in clay, stone, and metal. Finally, earth was placed over the burial, often in a precise sequence of soil and pebbles, probably to ensure stability of the monument. In some cases multiple burials were placed in the same location, adding to the size of the mound. The tallest of the mounds contained the remains of ten individuals, at least three of whom appear to have been important leaders on the basis of the artifacts found alongside them.

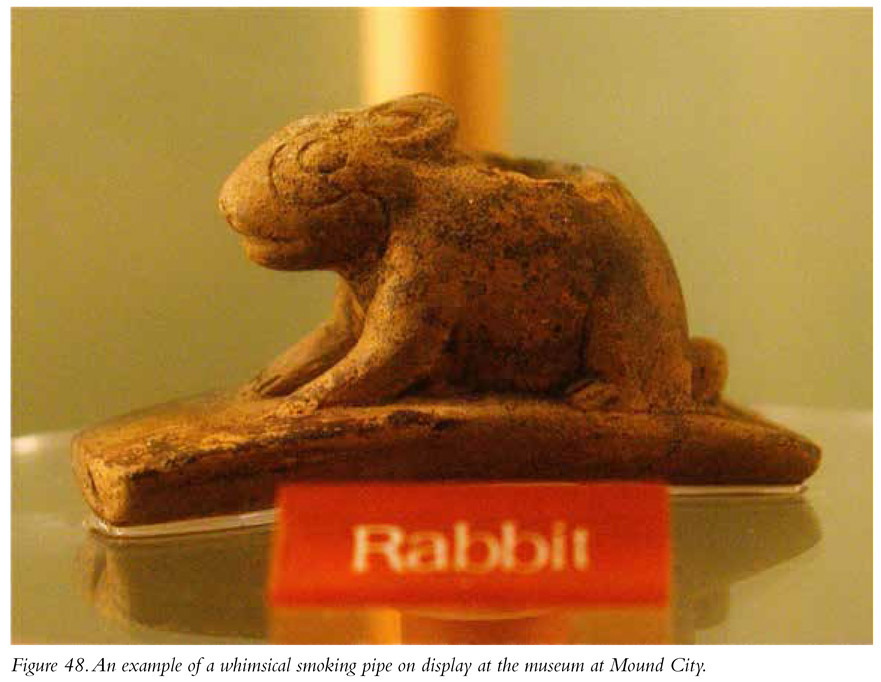

The on-site museum is extremely well done, with lots of splendid artifacts excavated at the site on display. Of course the beauty and skill reflected in these grave goods, perhaps intended for use by the deceased in the afterlife, are impressive and reflect the importance of those buried in the mounds, perhaps their economic wealth, social status, and political power. There are a number of beautiful copper cutouts in the shape of birds (I.8). One of the burial mounds is called Mica Mound because of the beautiful cutouts made of that material in the form of headless, handless, and footless human forms; the plumed heads of birds; and human hands. One person buried in the mounds was interred with an astonishing 200 carved smoking pipes, all produced in an array of various kinds of stone. These pipes are lovely, beautiful, even whimsical works of art. Many are in the shape of animals including bobcats, beavers, birds (raven, falcon, owl, heron), rabbits, and frogs (Figure 48). In most cases the bowl of the pipe where the tobacco was placed is located on the animal’s back. A hole was drilled from the mouthpiece to the bowl, serving to draw smoke into the lungs of the smoker. The person smoking the pipe would draw in the smoke while looking directly into the eyes of the animal represented on the pipe. Nicotine affects perception; higher nicotine content produces more of the effect. Native tobacco had a very high nicotine content, so odds are that smoking one of these effigy pipes had a mild psychotropic effect. Giving our imagination free reign, it’s easy to picture the smoker making a profound connection with the spirit of the animal represented on the pipe.

Walk through either of the entrances marked by breaks in the earth wall, and imagine the burial ceremony of a local ruler some 2,000 years ago. The remains might have been brought to a wooden structure, where cremation occurred. Then, with the remains placed in a shallow pit in the floor of the structure, a substantial mound was produced by placement of thousands of basketfuls of earth in a circular footprint over the burial building, rising to a point at its apex.

Why Is Mound City Important?

Mound City reflects, perhaps better than any other site in the American Midwest, the kind of social differentiation or stratification that characterized the native cultures we today call the Adena and Hopewell. Most people in these cultures were buried in plain, unassuming graves, but some people with special status in life—likely political rulers, religious leaders like shamans or priests, and just plain rich folks—got special treatment in death. They received their own tombs and burial monuments and were interred with items that were valuable as a result of the difficulty of obtaining the raw materials as well as the length of time and amount of skill required for their production. Walk around a modern cemetery today and note the differences in the size, raw materials, and characteristics of different grave markers; it’s much the same thing in the mound tombs. The memorials we construct for our deceased reflect how those people were perceived in life as well as the economic status of the loved ones who erected those memorials. The same was true for the Adena and Hopewell.

As noted earlier, “Hopewell” is the name given to a culture that developed in the Ohio Valley beginning about 200 BC. The Hopewell Culture is characterized by construction of conical burial mounds, social stratification with great chiefs or rulers whose remains were placed in the burial mounds, the creation of what appears to have been expansive ceremonial spaces enclosed by geometrically precise walls of earth, long-distance trade, and the creation of spectacular works of art from raw materials only available hundreds of miles away from the Mound City necropolis: copper and silver (Michigan), obsidian (Wyoming), mica (Kentucky), and shell and sharks’ teeth from the Gulf of Mexico.

Site Type: Burial Mound, Mound Enclosure

Wow Factor: *** Though the site has largely been reconstructed, the work involved in building the original “city of the dead” is very impressive.

Museum: ***** The artifacts recovered during excavation of this and associated sites are remarkable in their beauty.

Ease of Road Access: *****

Ease of Hike: *****

Natural Beauty of Surroundings: **

Kid Friendly: **

Food: Bring your own.

How to Get There: The park is located in Chillicothe, Ohio, 2 miles north of the intersection of US 35 and OH 104.

There are plenty of signs showing the way. To find Mound City using Google Earth, just punch in the following coordinates: 39 22’26.62”N 83 00’26.14”W

Hours of Operation: The visitor center is open daily 8:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. Memorial Day through Labor Day; 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. the rest of the year. Closed Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day.

Cost: Free

Best Season to Visit: Any time

Website: www.nps.gov/hocu/historyculture/mound-city-group.htm

Designation: National Historical Park