Chaco Culture National Historical Park • Nageezi, New Mexico

Journal Entry

March 9, 2015

There are two primary rationales for writing this book. The first is to inform you, the reader, of the amazing and spectacular archaeological legacy left behind by the first inhabitants of what was to become the United States. Fair enough. The second, rather obviously in a book that advertises itself as a “time travel guide,” is to encourage you to conduct your own treks through American antiquity, to get off your collective butts and see for yourselves the still-visible shadows of that past. With that in mind, it might seem contradictory that I also sometimes feel just a trace of ambivalence about encouraging you to visit some of those places, especially those that are geographically isolated. That ambivalence is manifested in a long-standing controversy about the attendance figures at Chaco Canyon National Historical Park and whether the federal government should attempt to make access to the site easier. Chaco is an amazing place, and I truly want you to go there. But part of what makes it such a wonderfully evocative place is how alone you can feel there while encountering the past.

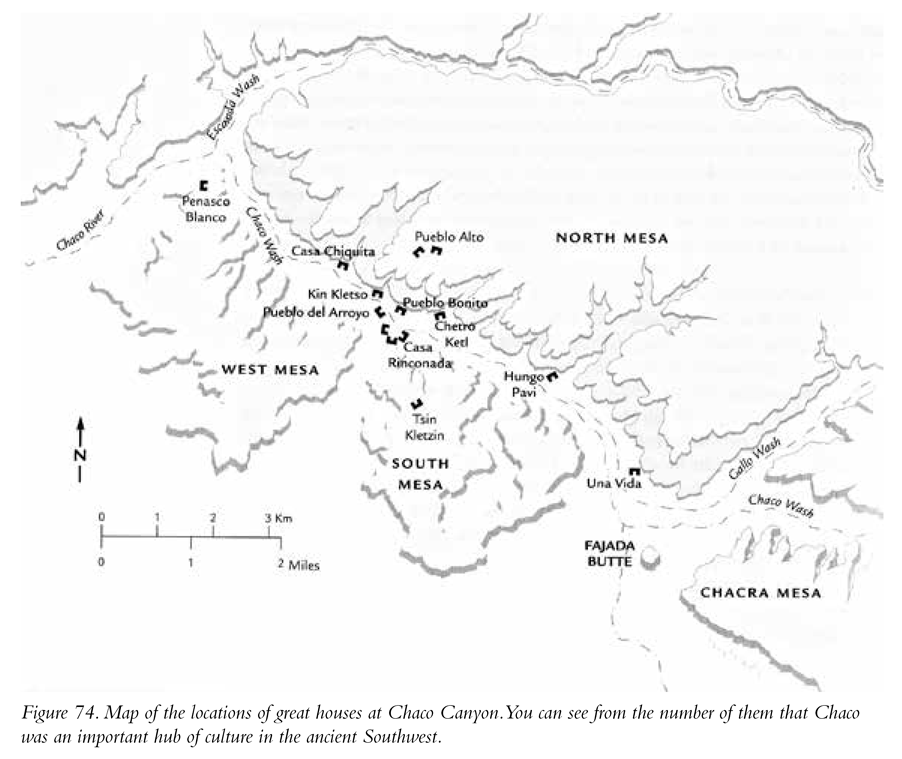

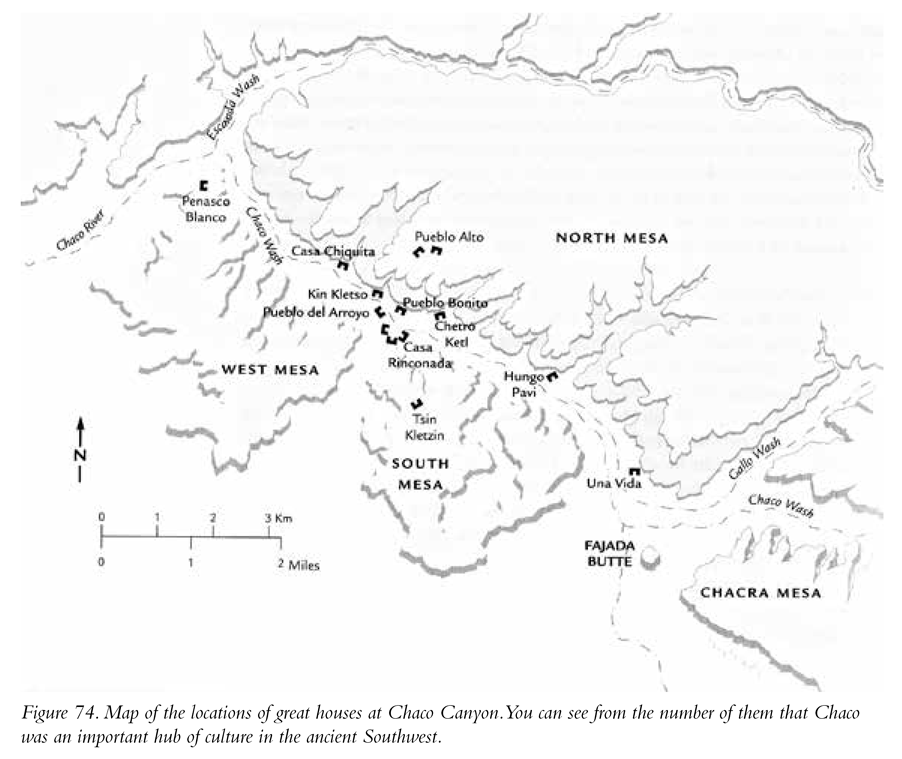

Chaco is remarkable. The ancient Chacoans constructed a series of more than a dozen truly monumental great houses—large, free-standing, many-roomed, multistoried structures—situating them in the unexpected, stark landscape of a desolate canyon in northwestern New Mexico (Figure 74). It’s a federal facility with a wonderful on-site visitor center and a bunch of well-maintained hiking trails. However, considering how incredibly mind-blowing the archaeological remains in the canyon are, attendance figures for this site are pretty low. In 2015 there were just a shade under 39,000 visitors for the entire year. Compare that to another of my fifty sites, Site 29, Mesa Verde National Park, where the 2015 attendance was close to 550,000, about fourteen times the figure for Chaco.

I have been to both places multiple times; they are both amazing, but my experiences at the sites have been entirely different. When you go to Mesa Verde, and I strongly encourage you to do so, you likely will encounter large crowds of visitors. If every one of them bought a copy of this book, then I’m okay with the crowds. Kidding! Wherever you go, there are tons of people. My best analogy might be this: I love Walt Disney World, but my experience there is always tempered by long lines and the enormous crowds (okay, and the price of a bottle of water). Chaco is different. It has never been crowded there during any of my visits. There isn’t a lot of traffic on the park road; and during hikes to and through the great houses, you might not even run into another person or family. Perhaps it sounds silly, but walking around at Chaco, it can almost feel as though you are discovering for the first time the remarkable architectural achievements of the inhabitants.

At least in part, Chaco’s relatively low attendance figures result from the fact that a long stretch (about 13 miles) of the primary access road is unpaved, can be a little rough, and is impassable after it rains. Further, there are few facilities at park headquarters. There is a primitive campground, but unlike Mesa Verde, there is no motel on-site. Unless you plan on camping there, you need to plan on leaving the park the same day you arrive. That can make for a very long day indeed. The park service further recommends that you not drive a recreational vehicle on the unpaved access roads. I have this bizarre image of driving the road into Chaco and passing the rusted-out hulks of broken-down RVs with still clothed human skeletons in the drivers’ seats. Gross, I know.

There has been a long-running discussion about paving the entire primary access road, which would certainly make travel to Chaco substantially less problematic. With paving, food and motel chains would be more likely to build facilities near the beginning of the access road to serve the likely surge in visitors. And therein lies my ambivalence. I certainly want to encourage you to visit Chaco. However, too much success in that will change the experience for those willing to go to the trouble to visit it as it is now. In a small way, right now you have to “earn” Chaco with a longish drive on an unpaved road. Maybe that’s a good thing. But if it prevents more people from experiencing Chaco, maybe it’s not.

What You Will See

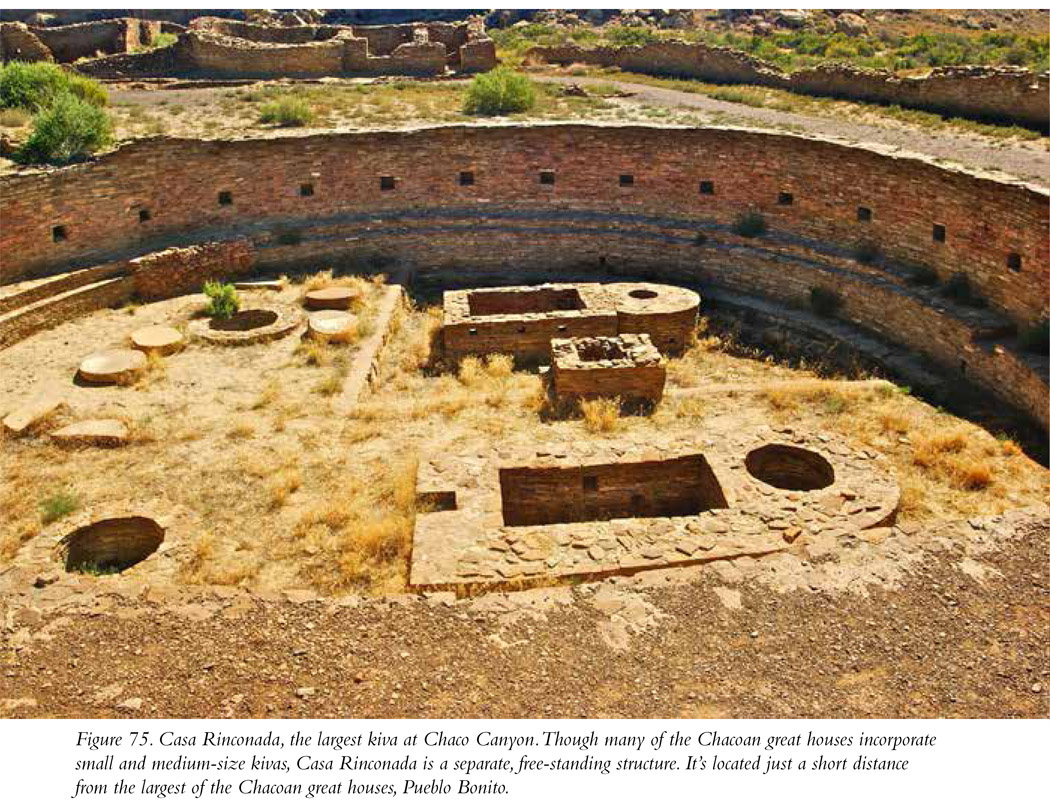

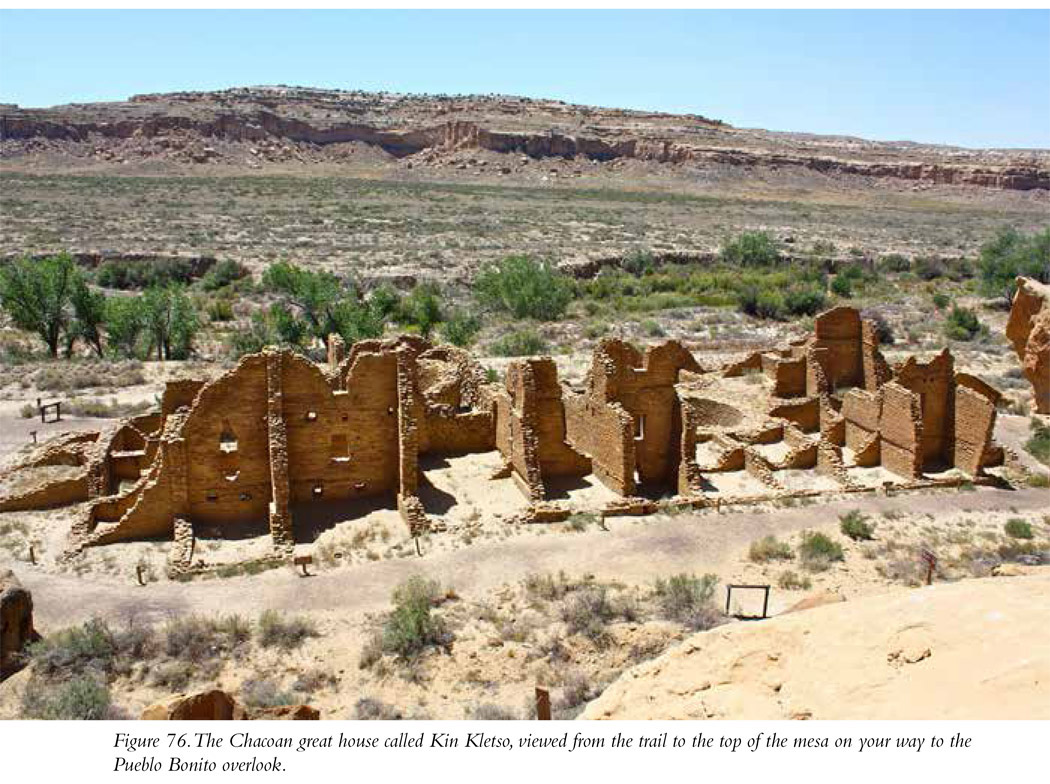

Built between AD 850 and AD 1150, the great houses of Chaco are astonishing bits of architecture and art. They are massive; must have required a tremendous amount of cooperative, communal labor; and reflect a great sophistication of engineering and construction. After reaching the visitor center, paying your entrance fee, and looking at the exhibits, you can drive the 9-mile paved park road loop, which takes you to five of the primary great houses at Chaco: Una Vida (there’s also a cool petroglyph panel on the cliff above the building), Hungo Pavi, Chetro Ketl, Pueblo Bonito, and Pueblo del Arroyo. A 2-mile round-trip hike from the Pueblo Arroyo parking area brings you to two more impressive structures: Kin Kletso and Casa Chiquita. The masonry incorporated into each of the great houses is quite beautiful, consisting of quarried and “dressed” stones; interestingly, each house’s stonework is unique. The individual stones used in the construction of some of the houses are flat slabs; in others the stones have been shaped into bricks; and some houses change up the individual courses or layers of stones, producing interesting linear patterns. Along with the many interconnected clusters of rectangular rooms, each great house also has several of the round ceremonial structures called kivas. These circular rooms have a bench along the base of the interior wall, niches positioned along those walls, sockets for large wooden beams or posts that held up the roof, masonry vaults, and a stone-lined hearth on the floor. Check out the reconstructed kiva at Site 30, Aztec National Monument for a peek at what the many Chaco Canyon kivas looked like. Case Rinconada (Figure 75), accessible along a short trail from Pueblo Bonito, is an enormous free-standing kiva with an additional cool feature—an underground passageway that leads from outside to the floor of the kiva. One can imagine priests dressed as spirit beings entering the kiva from that tunnel, as if arriving from the underworld. Amazing. Though the roofs and ceilings are gone, the walls of some of the great houses are in good condition; you can walk through them, affording an up-close and personal view of the living spaces of the Chacoans. It’s all very, very cool.

Though you can conduct essentially a car tour of five of the major buildings, parking and taking very short hikes up to them, I also highly recommend getting out of your car and doing a little more serious hiking. My favorite trail, and the one I most highly recommend, takes you to the top of the mesa and the Pueblo Bonito overlook (Figure 76). Pueblo Bonito alone is worth the price of admission to Chaco; the largest of the great houses, it contains more than 800 rooms in a single, three-story structure (I.18). You can walk through the building following the park service trail, but the best way to see Pueblo Bonito is from above (I.19). The mesa trail lets you see it that way. I admit that it is a bit strenuous, but not overly so—the elevation difference from the bottom of the trail to the top is only about 240 feet. Making your way to the top is a tiny bit scary, but only briefly at the beginning. As you hike up the trail, in a very short distance from the trailhead you will reach a rock crack through which you will walk to the top. It’s not so narrow that you’ll be afflicted by claustrophobia; and if you have a fear of heights, you’ll feel much safer as soon as you reach the crack. You do have to scramble over some boulders along the way, and there is some minor hand-over-hand climbing involved. Once you reach the mesa top, you’ll pass out of the crack and then walk a bit to the overlook. The mesa is wide; if you are afraid of heights, just don’t walk close to the edge and you should be fine. In 0.7 mile the trail splits; the trail to the left brings you to a mesa top great house, the Pueblo Alto Complex. If you hike up to Pueblo Alto, the trail loops around back; in 2.5 miles you’ll be at the other end of the trail you began on. If instead of taking the trail to the left you continue straight along the rim of the mesa, you’ll arrive shortly at the Pueblo Bonito overlook. The view is awesome and provides a particularly useful perspective of the 800-room dwelling. The only word I can use to adequately describe the view: Wow.

Petroglyph Trail is a very short and easy hike (0.3 mile one-way) along the cliff face behind and between two of the great houses, Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito. There’s a parking lot about midway between these two great houses from which you can access both structures and check out the Petroglyph Trail as you walk between them. There are some cool petroglyphs there; my favorite is the image of a mountain lion.

Another area with even more interesting rock art can be found farther to the northwest on a hike past the great house Casa Chiquita. The entry to that trail (signed “Petroglyph Trail” though it’s not the Petroglyph Trail mentioned above between Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito) is about 1.25 mile from the Pueblo del Arroyo parking lot. The rock art is spread out across a distance of about 0.3 mile. That petroglyph trail brings you back to the main trail you were on originally (the Peñasco Blanco Trail). From there you can turn left and hike back to the Pueblo del Arroyo parking lot (a bit more than 1.5 miles, making that entire trek a 3-mile hike). If you continue past the end of this petroglyph trail and turn right, in about 1.5 miles you’ll come to a side trail to the left that brings you to another mesa-top great house, Peñasco Blanco, and another trail to the right that brings you to the very impressive super-nova pictograph. From the Pueblo del Arroyo parking lot, past Casa Chiquita, through the petroglyph side trail, to the supernova pictograph, and then back to the parking lot is about 6.5 miles. It’s long but flat, and well worth it. (Check out the map on the Chaco Canyon National Park Service website for more information about these and other trails at the site: www.nps.gov/chcu/planyourvisit/upload/CHCU_park2006%20UPDATE.pdf.)

Why Is Chaco Canyon Important?

Chaco is unique. Nowhere else did the native peoples of the American Southwest build such a dense concentration of large structures, and we’re not sure why they did so. You’d think, Okay, it’s something like a part of a modern city where there’s a dense concentration of apartment houses, but that explanation doesn’t hold up. Interestingly, there’s not an abundance of household debris in the canyon. The archaeological evidence, or lack of it, actually seems to indicate that the population of the canyon was substantially lower than might be expected based on the number of apartments available in the dozen or so great houses located there. So what was the function of those great houses, if not for habitation? It may be that all the labor that went into constructing all those rooms in all those great houses was intended for ceremonial reasons. The building themselves are aligned to points on the horizon of astronomical significance, important points marking the rising and setting of the sun and the moon during the year. It’s almost as though the Chaco great houses are part of a giant celestial calendar. Other evidence related to a calendar is located midway up Fajada Butte, southeast of the biggest concentration of structures. There the inhabitants etched a spiral petroglyph onto the rock face right behind a crack in a rock. The sun streams through that crack, forming what researchers have called a “sun dagger” that crosses directly through the spiral on the day of the summer solstice.

The great houses are an example of “public architecture” and may have been intended to mark the canyon as the spiritual and economic center of the Chacoan cultural universe, a place of pilgrimage where residents, not of Chaco but of more than a hundred inhabited great houses located many miles away from the canyon, came together to spend some time, trade, have festivals, and worship. Chaco does seem to have been the center of that universe for a period of time. Analysis of aerial photographs of the region reveals the presence of an elaborate and sophisticated system of roads leading to and from Chaco.

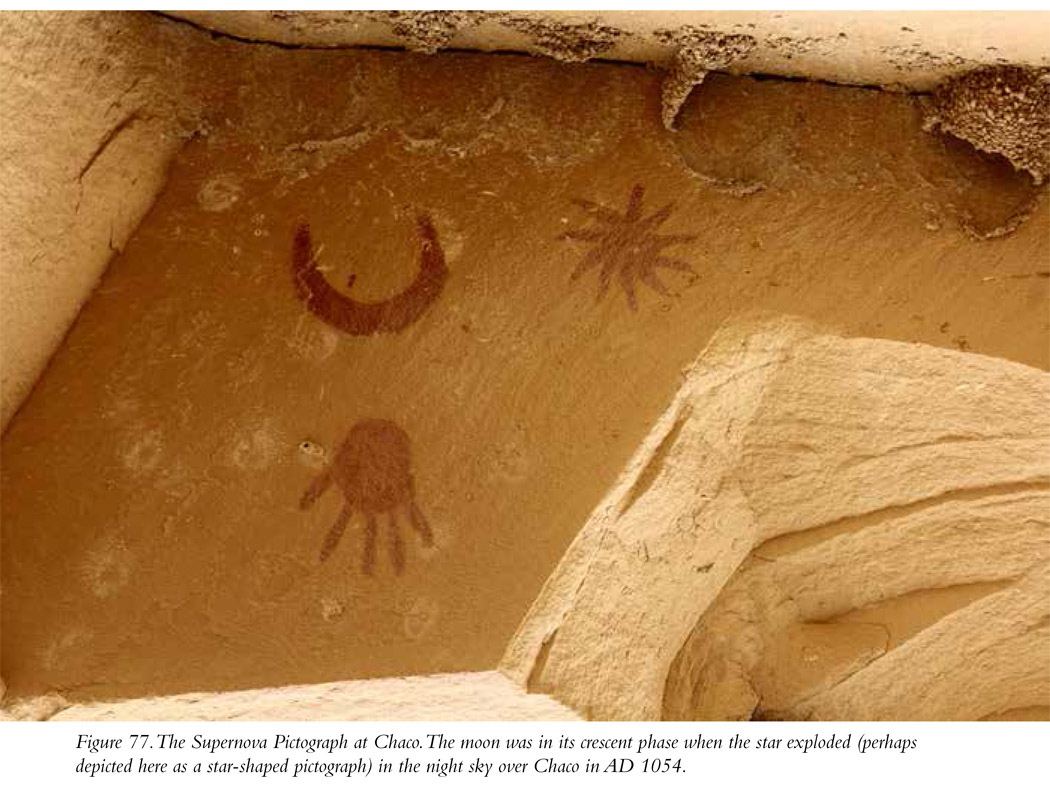

One more thing. If you take the trail from Pueblo del Arroyo past Kin Kletso and then past Casa Chiquita, out beyond the Petroglyph Trail you’ll see an interesting pictograph panel with what appears to be a crescent moon and a starlike object nearby. Based on the appearance of the pictograph and the timing of the construction of the Chaco great houses, it has been suggested that the pictograph is a representation of something the people at Chaco actually saw in the sky: a supernova that resulted from the explosion of a star in what we call the Taurus constellation (Figure 77). Today called the Crab Nebula, the star exploded in an unimaginable paroxysm in AD 1054. We know exactly when it exploded because Chinese astronomers also saw it and recorded it in their journals. It was, they said, bright enough to be seen in the daytime sky and as bright as a quarter-moon at night. The location of the star pictograph at Chaco, juxtaposed with the image of a crescent moon, matches what we know about the phase of the moon when the star exploded. It cannot be proven definitively that the pictograph you’ll see at Chaco is a painting of this celestial event, but it certainly is a fascinating possibility.

Site Type: Great House, Petroglyphs, Pictographs

Wow Factor: ***** The great houses at Chaco should not be missed. Pueblo Bonito is one of the most impressive buildings produced by Native Americans.

Museum: *****

Ease of Road Access: *** Part of the road is unpaved. It’s not terrible and you won’t need four-wheel drive, but it can be bumpy.

Ease of Hike: There are lots of hikes in Chaco, from very short walks from turnouts and parking lots to ruins of great houses to much longer and far more strenuous hikes with lots of elevation changes. Check the website for details.

Natural Beauty of Surroundings: ***** Starkly beautiful. By the way, Chaco has been designated a “dark sky region.”

It’s a great place to see the stars at night with very little light pollution.

Kid Friendly: **** Energetic kids will love Chaco. There are lots of places to expend energy, as well as lots of lizards and little furry critters.

Food: Bring your own.

How to Get There: The best way to access Chaco is from the north from US 550, which you can pick up in Bloomfield, from the north, or Cuba, from the southeast (that’s Cuba the town, not the island nation). From mile marker 112.5 on US 550, head south on CR 7900/7950. Take a right onto CR 7950 when it peels off CR 7900, which continues straight (to another site, Pueblo Pintado). CR 7950 will take you to the visitor center. Altogether, once you turn onto CR 7900/7950, it’s about 21 miles to the visitor center, 13 of which are on a dirt road whose maintenance is a bit, um, casual.

You can also access Chaco from the south. From NM 9, go north on NM 57. This route is rougher, on 20 miles of not-so-well-maintained dirt road.

Hours of Operation: Open daily 7 a.m. to sunset. The visitor center is open 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Chaco is closed on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day.

Cost: See website.

Best Season to Visit: Summer is hot, but you never know. I’ve been to Chaco in August and the temperature didn’t get above the high 80s. Spring or fall might be better.

Website: www.nps.gov/chcu/index.htm

Designation: National Historical Park; World Heritage Site