Ancient America’s hidden history revealed!!! Okay. I admit to feeling a little disingenuous opening with that headline. Technically it is accurate, but the hyperbole is readily apparent given the overabundance of exclamation points.

This book does indeed reveal “ancient America’s hidden history,” but not in the way that it’s “revealed” in far too many television documentaries, cable series, websites, and popular books about our country’s past. These programs, sites, and publications are replete with stories of ancient aliens, paranormal Sasquatches, lost continents, and wandering Templar Knights. In truth, many of these sources don’t reveal America’s hidden history; they just make it up.

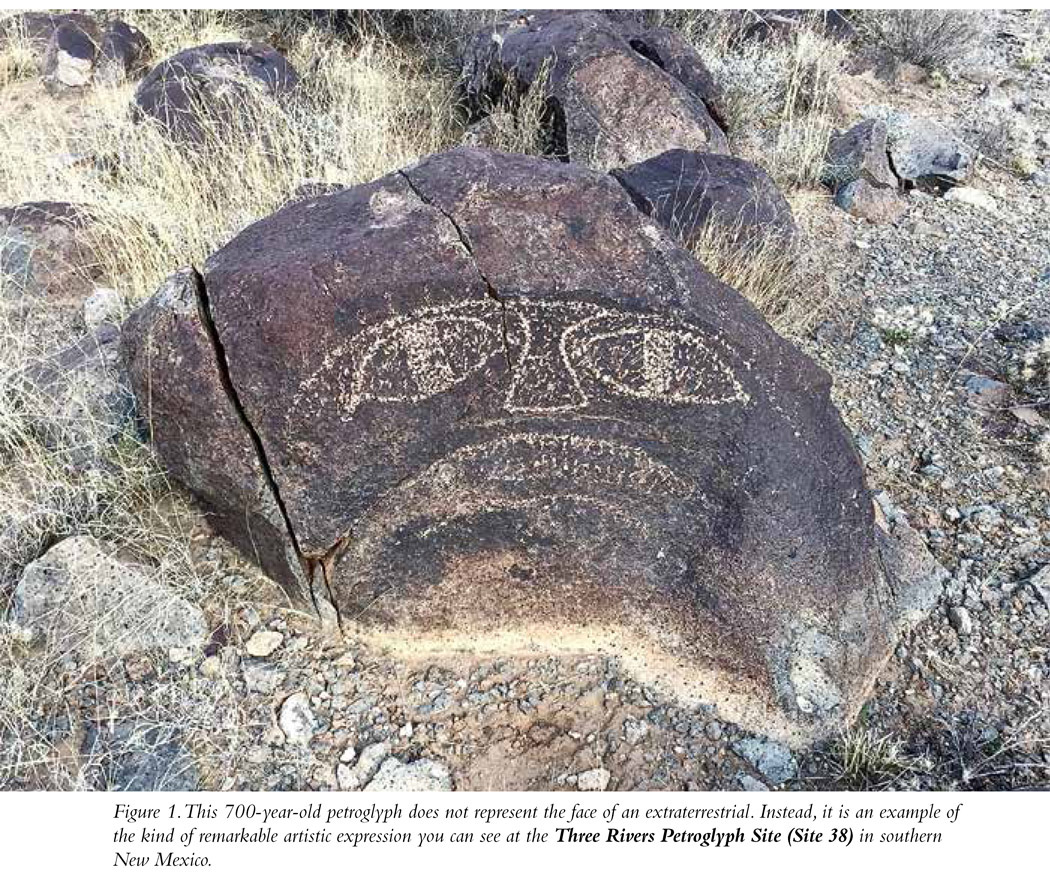

I will not be exposing here the secret truth about extraterrestrials visiting North America in antiquity. I can confidently report that, despite the claims made on a certain cable TV series, ancient aliens did not land in North America and inspire rock art depictions of space-suited extraterrestrials. But that doesn’t make the rock art I will be sharing with you any less beautiful, interesting, or worthy of attention (Figure 1). The artwork is truly amazing, but don’t take my word for it. Go see it for yourself.

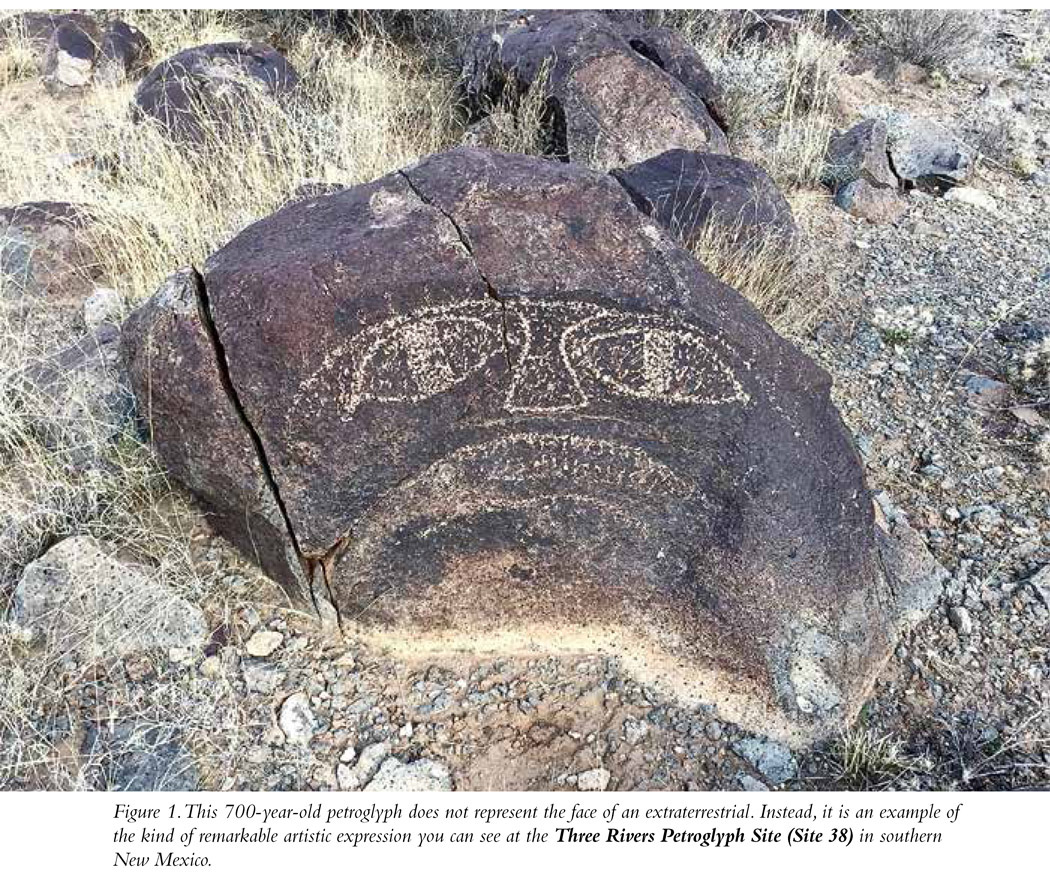

Also, I won’t be talking about Atlantis. Despite the claims of Ignatius Donnelly, the nineteenth-century popularizer of Plato’s allegory of a lost continent, the mound-building cultures of the American Midwest and Southeast were not inspired by Atlanteans escaping the cataclysmic destruction of their homeland. It’s a dead certainty that American Indians built the mounds, and that’s far more interesting than fantasies of lost Atlantis. Best of all, the mounds are still there for us to visit and experience for ourselves (Figure 2). In this book, I hope to inspire you to do exactly that.

There is indeed a hidden history of America’s first peoples, and helping you discover it is one of my goals. That history hasn’t been hidden intentionally. There’s no occult conspiracy on the part of the Smithsonian, NASA, the Illuminati, the Rotary Club, or even professional archaeologists like me. No, the “hidden history” I’m referring to is the result of general ignorance and historical amnesia. It’s also due, I sheepishly admit, to a failure on the part of archaeologists—myself included—to get the word out about the fascinating true stories of American antiquity.

Most people are unaware of, and will likely be very surprised by, the high level of engineering, architectural, and artistic sophistication reflected in the fifty archaeological sites and places profiled here. Regardless of all those discussions in your high school social studies class, and even though you mostly paid attention in your introductory college course in anthropology, the term “American Indian” or, if you prefer, “Native American,” likely conjures up images of movie or television stereotypes. Indians live in tepees. They’re horseback-riding nomads. They wear feathered headdresses, hunt buffalo, and scalp settlers; and when they’re done scalping those settlers, they smoke peace pipes with the survivors. Maybe, especially if you live in the Northeast, the image with which you’re most familiar depicts American Indians living in wigwams, planting a lot of corn, and being the suckers who shared that corn with the Pilgrims just before those colonists returned the favor by giving them smallpox.

But here’s the deal. Some American Indians were nomadic, but not all. Some lived in tepees, but not all. Many relied on corn for subsistence, but not all. Some now run spectacularly successful casinos, but not all. Okay, they do all make fry bread, but can you blame them? It’s just so delicious. But back to my point. The sixteenth-, seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century European explorers and settlers of North America encountered a variety of cultures as broad as that seen anywhere in the world. Explorers and settlers in the Midwest and Southeast wrote about their encounters with vast empires of pyramid-building farmers whose quite sedentary population centers were flanked by miles of cornfields and whose societies were ruled by powerful kings. European writers described peaceful farmers in the American Southwest living in enormous, finely constructed and elaborate adobe and stone apartment complexes. Other writers in the Southwest recorded the presence of beautiful buildings ensconced in seemingly inaccessible cliff niches, leaving the impression of breathtaking castles suspended in midair. Others remarked on the awe-inspiring natural galleries where, by etching into or painting onto rock surfaces, ancient artists shared their spiritual world by creating tens of thousands of depictions of a broad array of complex geometric forms, naturalistic animals, and spirit beings. The remains of many of these monuments, sites, and works of art still exist—and you can visit them.

Giving Credit Where Credit Is Due

Some European explorers were so impressed by the remains and ruins they saw in the canyons, flood-plains, cliff faces, and prairies of North America they denied that the ancestors of the living native peoples they encountered could have been responsible. For example, Montezuma Castle in Arizona wasn’t built by followers of the Aztec king who bore that name. That label was bestowed by Europeans who were of the opinion that only a great and sophisticated culture, like that of the Aztecs, could have constructed such an impressive and remarkable building. The Europeans were half right. The builders were bearers of a great and sophisticated culture, but not that of the Aztecs. The responsible party was a tribe of Native Americans, ancestors of the modern Hopi Indians. Go see the place for yourself; I’ll tell you how in this book.

The same holds true for the northern New Mexico site that was given the name “Aztec,” again in the false belief that the monumental structure found there, with its beautiful and elaborate stone masonry, must have been built by a highly accomplished civilization. It was, but here again the site’s name incorrectly implied that this civilization was not that of local Indians but instead originated in Mexico. Toltec Mounds in Arkansas is another impressive American Indian site, this one with monumentally scaled earthworks that were, literally, great pyramids produced in soil. The site is named for a Mexican civilization, the Toltecs, who predated the Aztecs. These sites were named in a way that denied their connection to the native peoples of the United States. Again, you can and should see these places for yourself.

One of the purposes of this book is to encourage you to visit as many as you can of fifty of the most amazing archaeological sites located in the United States (Figure 3). In the pages to follow, I’ll explain the importance of these particular sites, and also provide practical information to facilitate your journey through time.

The hidden history we’ll explore in this book is one that is “hidden in plain sight.” It is a history that you can examine and see for yourself. The research I conducted for this involved a personal archaeological odyssey. Along the way, I visited each of the fifty sites presented here. You won’t need to leave your easy chair to appreciate these places, but I hope I can inspire you to conduct your own archaeological odysseys to gain a personal appreciation for America’s amazing ancient past.

Why Visit the Past?

In his work The Go-Between, English novelist L. P. Hartley phrased it this way: “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” It’s a nice bit of phrasing, and in a sense it’s an important goal of every archaeologist to serve as a tour guide for non-archaeologists who wish to visit the “foreign country” that is the past.

A virtual visit through the pages of a book (like this one) is interesting and instructive, but if you can, plan an actual visit to the places where ancient people lived. Our species has been around for a vast stretch of time, and we humans have found amazingly varied ways to adapt to the spaces and places in which we have lived. Our modern human condition has evolved from the lives lived by past peoples; using the archaeological record to explore the diversity of those peoples who have gone before can provide important insights into who we are today. And there’s no better way of doing that than seeing the sites for yourself.

Think about it; open the newspaper on any given day and you will read stories of global warming—or cooling; of recessions and depressions; of resource depletion, ethnic violence, and warfare. The archaeological record shows that ancient members of the human family have been there and done that. Warfare, environmental degradation, climate change, technological change, resource depletion, drought, and poverty are not new challenges facing our species. When you visit the sites presented in this book, you will be directly confronted by evidence of conflict, of the impacts of short-term environmental disasters like droughts and long-term processes of climate change, as well as the devastating effects of economic collapse. The past is indeed “a foreign country,” one that’s important to visit for the insights it may provide on these and many other issues vexing modern humanity.

If all that sounds way too depressing, not the kinds of things you want to be reminded of when taking the kids on vacation, fair enough. Rest assured that the places I am encouraging you to visit are also just incredibly cool—monuments to the unexpected abilities of people who, from our lofty perch in the twenty-first century, we too often view as simple or primitive.

Okay, so where would you go to visit the past? Ordinarily, the word “archaeology” conjures thoughts of the exotic cultures of ancient Egypt (vast pyramid complexes; the Great Sphinx!), Mexico (Maya temples!), or Greece (the Parthenon!), and with good reason. These are incredible monuments, the intriguing shadows cast by past cultures. But you don’t need to go quite so far away to visit the past. And you won’t need a passport. The fifty sites featured in this book are not in exotic or foreign locales but instead can be found along America’s byways and in its parks and backyards.

In our own country we have an amazing past populated by the remnants of the communities of our nation’s first inhabitants. Ancient bison hunters and first farmers, builders of earthen pyramids and adobe cliff houses, stone calendar makers, cave painters, and makers of giant animal images in earth and stone; all lived here, in America, and left behind in great profusion evidence of their artistic and technological genius. The archaeological record of North America is intensely fascinating and worthy of respect, attention, and preservation (Figure 4). It’s also worthy of a personal visit by you.

The sites profiled here certainly do not represent an all-inclusive digest of archaeological sites open to the public across the United States. Nor do these fifty sites constitute an exhaustive representation of the many fascinating sites spread around this country. In winnowing that vast collection to fifty profiles, I chose what I felt were the fifty most important and visually interesting sites. These sites will leave any visitor with a uniquely personal perspective of the remarkable histories and spectacular accomplishments of the first Americans. This is my recommended list of “the fifty ancient sites in the United States you should see before you die.” Fairly or not, many states (including my own, Connecticut) have no sites in my listing. It’s not that there aren’t important sites in these states—there are; but none made it into my top fifty according to the criteria I employed. To be included in my listing, a site had to be iconic in some sense, representative of a specific period in American antiquity, and emblematic of a particular ancient culture or region. There is some personal favoritism here; my list of fifty is unlikely to be exactly the same as a list of “fifty top sites” from another archaeologist. Almost all of my fifty have been officially recognized as significant. Many are listed on the federally administered National Register of Historic Places, an honor roll of important historical sites; some have been designated as National Historic Landmarks; and four have even been recognized as World Heritage Sites, a listing that includes Stonehenge and the Giza pyramids.

My fifty sites also share another essential characteristic: They all are open to the public. This is to encourage, even inspire, you to see some of these wonderful places for yourself—to engage in your own archaeological odyssey. My hope is for you to visit the past, travel through time, surround yourself with antiquity, expose your kids or grandkids to America’s archaeological heritage, be surprised, learn lots, and, most important, have a great trip.

Before we begin exploring specific locations, some basic background about America’s ancient past will help you understand and appreciate the fascinating places listed here. In the next section, Ancient America, I’ll paint a quick picture of the climate and geography of North America over the last several thousand years. We’ll also discuss the diverse peoples who first settled—and whose descendants continue to populate—this continent. This section also provides narrative background about the different genres of sites included in the book: First Peoples; Mound Builders; Cliff Dwellings, Great Houses, and Stone Towers; and Rock Art—the vast outdoor, ancient art museums filled with “galleries” of pictographs (painted images), petroglyphs (pictures etched, incised, and pecked into rock surfaces), and geoglyphs (ground drawings on a massive scale). The remainder of the book explores the fifty archaeological sites I encourage you to see for yourself, grouped according to genre.

Site profiles in each of these four groupings are presented alphabetically by state and further broken down into separate types. You will quickly realize that the different genres roughly correspond to geographic areas of the continental United States. I’ll begin with First Peoples, a category with a single site where you can visit a rockshelter lived in by a group of the first humans to settle North America more than 13,000 years ago (Site 1, Meadowcroft Rockshelter). There are many sites in the United States where the remains of those First Peoples have been studied, but very few are open to the public, and fewer still allow you to see the actual remnants of the archaeological excavation.

From there we’ll travel across the East, Midwest, and Southeast, where the most prominent remains consist primarily of mounds, mounds, and more mounds. In the Southwest the defining features are cliff dwellings, great houses, and stone towers. Rock art sites are also clustered predominantly in the Southwest, although there are stunning sites stretching into the Rocky Mountains and closer to the Pacific Ocean. At the beginning of each grouping of sites, you will find a map identifying the location of specific sites relative to one another.

At the beginning of each site profile, I offer a narrative of my own experience visiting the site, based on a Journal Entry I kept during my visits to the past. These reflect my personal reactions to the remarkable sites produced by America’s first peoples.

This entry is followed by a straightforward description of What You Will See: the incredibly cool art or mounds or cliff dwellings or freestanding structures you will encounter in your journey through time.

Next I answer the question Why Is [Site Name] Important? Part of my process of compiling a list of fifty ancient sites included a consideration of their incredible beauty and even mystery—their “wow factor.” However, I am a college professor, and I’d also like you to appreciate these sites for what they teach us about the intellectual, artistic, and spiritual lives of the ancient peoples who produced them. My fifty sites aren’t just uniquely beautiful and impressive; they are also uniquely informative about the lives of the first Americans and help us understand America’s past.

Each site profile closes with an overview of the practical details you’ll need to know as you plan your visit. This includes:

1. Site Type. I label each site by the primary features it offers the archaeological time traveler. The Mound Builders genre includes Burial Mounds, Enclosure Mounds, Platform Mounds, Effigy Mounds, and Villages. The Cliff Dwellings, Great Houses, and Stone Towers genre features those edifices. Finally, the Rock Art genre includes Petroglyphs, Pictographs, and Geoglyphs. Some sites possess characteristics of more than one of these type labels.

2. Wow Factor. I’ve also put together a rubric (one to five stars) for scoring some subjective elements, such as the site’s “wow factor.” My scorings are entirely subjective of course, but I think they are a pretty good guess at how beautiful, impressive, even astonishing you will find the sites to be. If I placed the site in this book, you can be sure I was pretty wowed by it, so every site has a pretty high score.

3. Museum. Here I let you know about any on-site museums.

4. Ease of Road Access. If a site gets five stars, it means that the route is entirely paved and you can drive there in your low-clearance, two-wheel-drive family sedan. Fewer stars imply a rougher road, and I let you know if it’s best to use a four-wheel-drive vehicle for safe access (true in only a couple of cases).

5. Ease of Hike. I like a good hike, but when I look at trail guides and see “strenuous,” “difficult,” “climbing,” or “lots of exposure” (meaning steep drop-offs along the trail), I get a little nervous, so I wanted to give you my subjective impression of the difficulty of the hikes. If you’re an experienced hiker, all fifty sites are easy to get to. If you hate hiking, sites with fewer stars might not be best for you. Trust me; while hiking back up and out of Site 40, Horseshoe Canyon, people were passing me by while I was trying to catch my breath. I survived, and the site certainly was worth the trek, but I figured you might like to be warned about some of the longer, steeper hikes or the ones with significant exposure to heights.

6. Natural Beauty of Surroundings. When you are hiking to or through an incredible archaeological site, you’re often going to be in the midst of a stunning natural landscape. Again, my scoring here is subjective, but it should give you a good idea of the site’s general surroundings.

7. Kid Friendly rankings are based on opportunities for running around and the potential for interactivity. If your kids are fine with just looking at amazing sights/sites, all the places in this book will be five stars for them. But some of the hikes may be a little easier than others for little ones; others offer more distractions for kids in general.

8. Food. It’s always smart to bring along a cooler with drinks and snacks, but some sites, especially those with museums, offer limited food choices.

9. How to Get There. I provide an address for use with your GPS and/or narrative directions for finding the site.

10. Hours of Operation. I tell you when the site is open to visitors, but always check the website I’ve provided for changes.

11. Cost. There is no cost to visit many of the fifty sites on my list. For sites located in national parks, you can purchase an annual “America the Beautiful” pass. That pass covers up to four adults in the same vehicle—and may save you money over the course of your trip. For a nominal fee, people age 62 and older can get a Senior Pass which provides a lifetime of entry to sites administered by the National Park Service. The pass also allows you to bring up to three additional adults when you visit. It is an amazing bargain. Outside the national park system, cost may vary by the age of visitors; some offer discounts, and prices may change by the time you read this book. While none of them are terribly expensive—these sites aren’t theme parks—your best bet is to check the relevant website for current prices.

12. Best Season to Visit. My recommendations are based primarily on weather, but also on crowds.

13. Website. Where available, I’ve provided the official website for the archaeological site. If there isn’t one, I provide a useful source for additional pre-travel research.

14. Designation: This includes the designation of the site—as a national monument, a state park, Bureau of Land Management property, etc. Also listed here is whether a site is a National Landmark, World Heritage Site, or similar designation.

Finally, when I refer to a site profiled elsewhere in the book, its name will appear in bold and will include the site number according to the table of contents (for example, Site 9, Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site).