![]()

There is no greatness where there is no goodness, simplicity, and truth.

—War and Peace, Volume 4, Part 3, Chapter 18

On June 9, 1881, Tolstoy, fifty-two and frustrated with his life, set out for the Optina-Pustyn Monastery, some seventy miles from Yasnaya Polyana, disguised in a peasant’s robe and bast sandals. Carrying a wooden staff, he traveled by foot, and was accompanied by luggage-toting bodyguards also in disguise: a schoolmaster and a valet whose thick red sideburns and large round face must have seemed fitting for his last name, Arbuzov, which, in Russian, is the genitive plural of “watermelon.” During their four-day trek through the countryside, these three men, taken for holy fools in search of alms, were offered lodging by their brothers and sisters in rural Russia. But even the night spent sleeping on the floor of an old peasant’s house or the stopover in Krapivna were not enough to ease the bleeding of Tolstoy’s badly blistered feet, unused to those poorly fitting shoes made of bark. As much as he wanted to experience Mother Russia in all of her expansive, foot-shredding authenticity, Tolstoy’s aristocratic instinct took over when he gave in and bought himself a thick, fresh pair of socks.

On the fourth day of their journey, the bedraggled, dust-covered trio finally arrived at their destination in time for dinner, but they were not allowed in the travelers’ cafeteria. Instead, they were sent to the commoners’ refectory, where they dined on borsht and kashaI and drank kvassII with the riffraff. Whether because his empty stomach wasn’t accustomed to such heavy fare, or because of the stench of the insect-infected third-class dormitory where they had been sent to sleep, the writer threw up violently that evening. At this point the concerned Arbuzov, pressing a ruble into the hands of one of the monks, insisted that they be upgraded to superior accommodations. Upgraded they were, to a small room already occupied by a cobbler, whose snoring kept the exhausted travelers up for hours. “Wake that man up and ask him not to snore,” Tolstoy whispered to his valet, who naturally did as he was told.

“So because of your old man I’m not allowed to sleep all night?” responded the startled cobbler. Fortunately for everybody concerned, the man turned his head to the wall and dozed off in silence for the rest of the night, and Tolstoy finally got some sleep.

The next morning, however, an even more serious problem arose. After gazing joyfully for hours at the monks working in the fields, Tolstoy returned to the monastery to learn that a rumor had spread that this rough-looking, shaggy-bearded wayfarer was no ordinary peasant, but Count Leo Tolstoy himself. As the monks started applauding and genuflecting before their famous guest in the monastery halls, Tolstoy knew his cover had been blown. “Hopeless,” he grumbled, and told his valet to unpack his boots and good shirt, after which he proceeded to meet with monastery elder Father Ambrosy, a confessor and counselor known throughout Russia, in search of spiritual wisdom and career advice. We don’t know what exactly transpired between the two men, but we may assume the Father’s response was less than satisfying, for the very next day Tolstoy and his fellow travelers returned home by train—first class.

Okay, so let’s get this straight: A middle-aged family man at the height of his intellectual and physical powers, the creator of War and Peace and Anna Karenina, a writer more famous than Dostoevsky and Turgenev, an all-around successful man with an annual income of 30,000 rubles ($85,000, or in today’s money, around $2 million), decides to make a miserable, four-day trek through the Russian countryside in order to meet a famous monk and ask him the question What should I do with my life?

Success, apparently, is not what we may have thought it was. And think about it, Tolstoy did, from a very young age as a matter of fact. His diaries and letters are full of painfully honest confessions about his passionate longing for success, along with a fear that he might actually achieve it, but for all the wrong reasons. “[T]here are things which I love more than goodness—for example, fame,” the twenty-five-year-old wrote in his diary. “I am so ambitious, and this feeling has been so little satisfied, that as, between fame and virtue, I fear I might often choose the former if I had to make a choice.”

Nor were his fears entirely unfounded. In his Confession, written some three decades later, Tolstoy looks back on his journey to fame and fortune: “Lying, stealing, promiscuity of every kind, drunkenness, violence, murder—there was not a crime I did not commit,” he wrote of his early years. Even his desire to become a writer was motivated by “vanity, self-interest, and pride.” The literary and financial success that did start coming his way was less than satisfying: “ ‘Very well, you will have 6,000 desyatinas [16,200 acres] in the Samara province, as well as 300 horses; what then?’ . . . Fine, so you’ll be more famous than Gogol, Pushkin, Shakespeare, Molière, more famous than all the writers in the world—so what?” His life, the internationally famous writer concludes, “was meaningless and evil.”

Given all he’d achieved when he wrote this, we might be mildly amused by Tolstoy’s public self-immolation, but the fact is, he wasn’t laughing; he was deadly serious—indeed, he nearly killed himself. So what happened to bring him to this point?

Long before Rick Warren could make a lucrative business out of it, Tolstoy was talking about the “purpose-driven” life, and the unhappiness that may ensue from a life focused only on personal gratification, or achievement for achievement’s sake. True, most of us will never be forced to justify the worthiness of a life that includes, say, an income of a few million dollars, the ownership of 16,200 acres of land, or the creation of two of the greatest novels ever written. Nonetheless we can surely relate to the challenge of defining what “success” really means to us, as well as the moral quandary that pursuing it and actually achieving it often puts us in.

“Success,” Tolstoy tells us in War and Peace, is an image, an idea, a mirage. It’s the elusive destination that you never quite reach, the pool of fresh water you glimpse in the desert. Once you’ve arrived, poof—it’s gone. Perhaps it was never there in the first place.

Take Pahom, a well-to-do peasant who is perpetually dissatisfied with his lot in life. Every few years this hero of Tolstoy’s 1886 story “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” uproots his family to go wherever he hears of a better landowning opportunity. One day he travels to the faraway land of the Bashkirs, where huge swaths of virgin soil can be bought for the amazingly low price of a thousand rubles. As much land as he can cover by foot in a single day will be his, provided he returns to the starting point by sunset. And so, off Pahom runs with his trusty spade, marking an irresistible little patch here, a to-die-for section over there. This land-buying spree goes on for hours until Pahom, suffering from exhaustion and noticing the sun dropping below the horizon, runs as fast as he can on his bruised feet while the Bashkirs cheer him on, and makes it to the finish line just in the nick of time. Whereupon he drops dead: “Six feet from his head to his heels was all he needed,” the story tells us, by way of an ending.

A harsh message, perhaps, but universal enough—and inevitably timely enough—that it continues to resonate with readers of all ages and walks of life. “We see a nice guy driving a BMW or somethin’ like that, and we’ll want to get that BMW, not saying that exact BMW, but we’ll wanna top ’im, so we’ll try to get a better BMW,” observed one resident at Beaumont Juvenile Correctional Center who had just read Tolstoy’s story as part of my course, “Books Behind Bars: Life, Literature, and Leadership,” in which University of Virginia students meet weekly with incarcerated youths to discuss classics of Russian literature. “It’s funny how you can read, kin’a, you know what I’m saying, literature from years and years and years ago and still apply it to life today, ya know what I mean?”

I do. See, for many years I was obsessed with being “successful,” without ever quite knowing what exactly I wanted to be successful at, or even what success was. No wonder I was perpetually frustrated. At the same time, even as my more competitive side kept pushing me to one conquest after another, there was a voice inside me urging me to seek some deeper sort of meaning. When I was a graduate student at Stanford, a professor at a monthly student-faculty meeting asked us if there were any issues we’d like to add to that day’s agenda.

“Sure,” I said with naïve enthusiasm. “Could we spend some time reflecting on our purpose in becoming Russian literature scholars?”

The room went silent, and people looked around nervously. Oops. I had obviously just made a big faux pas.

“The reason you’re here is to prove yourself,” glowered the professor who’d posed the original question. “The profession either accepts you or it doesn’t,” he added gruffly, as if personally insulted by my words.

The graduate students, myself included, dutifully nodded, of course. We were in no position to challenge this man’s authority; what’s more, we recognized in his response an all too familiar refrain we’d been hearing over and over since our college days: work hard, rack up the right credentials, jump through the right hoops, meet the right people, eventually publish in the right journals, and—voila!—academic success can be yours. But to what end? And at what cost? Were we all just emulous little Pahoms who’d come to graduate school in order to be turned into expert hoop-jumpers and skillful players in the game of academic advancement? And even if quite a few of us had, wouldn’t it have been rather interesting to have an honest conversation with one another about why we thought that game was worth playing in the first place? But the silence that often accompanies such questions, in academia as well as other professional contexts, can be deafening—and deadening. More recently, for better or worse, with the much-discussed crisis in the humanities now a serious concern within academia, and the future of our country a frequent topic of conversation outside of it, there is a renewed interest in precisely the sorts of big, naïve questions I had been asking in graduate school—the same sort of questions Tolstoy poses in his art with such unabashed directness.

As a matter of fact, I recently learned that the members of the Young Presidents Organization (YPO), a group of corporate CEOs under the age of fifty, chose to read “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” as part of their annual educational enrichment program. My brother, a member of the organization, couldn’t divulge details because of group confidentiality agreements, but he did say that Tolstoy’s story got these high-powered young executives talking about things high-powered young executives don’t often talk about in public. That these CEOs came to select a story whose message challenges much of what they have built their careers around is a testament not only to their intellectual courage, but to the urgency and relevance of Tolstoy’s message.

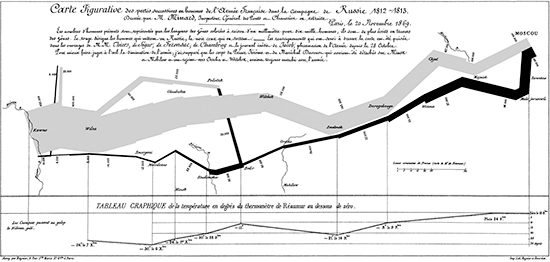

War and Peace, although written decades before “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” and admittedly a far less moralistic work, invites readers to grapple with some of the same issues. According to the history books being read by most Russian schoolchildren in the nineteenth century, Napoleon was the greatest military genius the world had ever known. One had only to look at the sheer quantity of countries and peoples he’d conquered. Tolstoy’s Napoleon, on the other hand, gloats as he’s about to take the Russian capital, only to find Moscow almost completely empty. Then, having given him their capital, the Russians promptly set it on fire. Napoleon has thus achieved his long-cherished goal, and what was it worth? The death of nine-tenths of his overextended troops, for one thing, on the long winter march back out of Russia. To illustrate this point another way, consider this famous graphic by French civil engineer Charles Minard depicting Napoleon’s march to Moscow and subsequent retreat. It first appeared in 1869, the year Tolstoy was finishing his novel:

Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia: the Costs of Success.

The gray shading represents the size of Napoleon’s army when he first crossed the Nieman River into Russia in May 1812 with 422,000 troops. It then traces the steady dissipation of his army down to 100,000 troops by the time he reached Moscow (in upper right). The black line describes the continual thinning of his army down to 10,000 soldiers by the time he recrossed the Nieman. Minard’s graphic shows visually in a single glance, then, what War and Peace illustrates narratively over hundreds of pages. The bottom line (literally) is that precisely when we think we’re winning, we might actually be losing, or even planting the seeds of our own destruction.

Every generation is affected by its own version of the Napoleon Syndrome, and the characters in War and Peace are no exception. Early-nineteenth-century Russians feared and resented Napoleon, yet many of them also tried to emulate him. This self-made man who rose from humble beginnings to become the conqueror of all of Europe appeared to be everything they were not: omnipotent, pragmatic, ruthless, and, above all, French. If you were an ambitious young Russian male living in 1805, then, and wanted to make a name for yourself, you could do no better than beating Napoleon Bonaparte at his own game. That is exactly what Prince Andrei Bolkonsky sets out to do.

At twenty-seven, Prince Andrei has it all: good looks, plenty of brains, enviable breeding, and an attractive young wife who not only turns heads, but melts hearts. None of it, however, is enough for this nobleman whose perpetual boredom with life is readily apparent in his slow gait and weary gaze. And so off to the army he swaggers, abandoning his pregnant wife and, through his father’s connections, landing a job as adjutant to Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov, commander in chief of the Russian forces. Smart, worldly young man that he is, Prince Andrei quickly makes himself useful to Kutuzov, advising him on military strategy, surveying battle plans, and disciplining unruly subordinates, who, understandably, aren’t especially fond of their new supervisor. But Andrei doesn’t care, for he is a man on a mission. Even after his participation in the battle of Schöngrabern, in which Russians successfully hold off the advancing French army, Prince Andrei himself fails to win the recognition he’s sought. Yet, the disappointed prince refuses to waver in his single-minded pursuit. And a little over two weeks later, on the evening before the battle of Austerlitz, he is ruthlessly honest with himself about that fact:

“I don’t know what will happen . . . I don’t want to know and I can’t know, but if I want this, want glory, want to be known by people, loved by them, it’s not my fault that I want it, that it’s the only thing I want, the only thing I live for. Yes, the only thing! I’ll never tell it to anyone, but my God! What am I to do if I love nothing except glory, except people’s love? Death, wounds, loss of family, nothing frightens me. And however near and dear many people are to me—my father, my sister, my wife—the dearest people to me—but, however terrible and unnatural it seems, I’d give them all now for a moment of glory, of triumph over people, for love from people I don’t know and never will know.” (264–65)

Whew! And I thought I was ambitious! What a load of inner demons this young glory seeker seems to be carrying around. Is he trying to prove himself to his imperious, emotionally distant father? To win the love he never received from his absent mother? Whatever the case, Prince Andrei is someone we have no problem recognizing from great literature, art, or even the evening news. From Achilles to Anna Nicole Smith, there are some people so obsessed by the allure of glory, they’re prepared to sacrifice everything for it—including their own lives.

As the battle begins, Prince Andrei watches a curious skirmish between a French and a Russian soldier in which the two men seem to be engaged in some kind of weird dance around a cannon. Absorbed by this sight, the bemused spectator is suddenly clubbed on the head by a French soldier. What upsets him in this moment is not that this blow might lead to his capture or death, but that it prevents him from viewing the denouement of that interesting little fight. Who’s winning? What’s the score? Opening his eyes some time later after plunging to the dirt, he searches for the skirmishing soldiers:

But he did not see anything. There was nothing over him now except the sky—the lofty sky, not clear, but still immeasurably lofty, with gray clouds slowly creeping across it. “How quiet, calm, and solemn, not at all like when I was running,” thought Prince Andrei, “not like when we were running, shouting, and fighting; not at all like when the Frenchman and the artillerist, with angry and frightened faces, were pulling at the swab—it’s quite different the way the clouds creep across this lofty, infinite sky. How is it I haven’t seen this lofty sky before? And how happy I am that I’ve finally come to know it. (281)

How is it I haven’t seen this lofty sky before?

Good question: How is it any of us fails to see the bigger picture, as we so often do, confusing the contentment we seek with the narrower visions of conquest we pursue?

Like Andrei, we frequently misunderstand the true nature of reality. Life, Tolstoy says, isn’t a fast elevator shooting us up to the top floor, but a continuous river of individual moments flowing endlessly into one another. The battle of Austerlitz, which would go down in history as a terrible loss for Russia, is one of the great moments of Prince Andrei’s life, but not for the reasons he might have thought. The majesty of battle would seem to be his for the taking (or at least the taking in), when wham!—life, in the form of a soldier’s bayonet, hits him over the head and knocks him into a new consciousness. Through the haze of his blurred vision, he sees clearly for the first time the immensity of the universe, indifferent to his worldly plans and ambitions. And for a brief moment he gets it. Watching Napoleon collect his human trophies from the bloody battlefield some hours later, the usually silver-tongued nobleman is momentarily struck dumb as Bonaparte suddenly turns to address him:

[But] to him at that moment all the interests that occupied Napoleon seemed so insignificant, his hero himself seemed so petty to him, with his petty vanity and joy in victory, compared with that lofty, just, and kindly sky, which he had seen and understood, that he was unable to answer him. (292–93)

Such silent reverie is, of course, alien to the society to which Prince Andrei belongs. When they gather to give a hero’s welcome to General Bagration for his brilliant victory at the battle of Schöngrabern, a few chapters later, the Moscow socialites are as chatty as ever. Alas, news of the Russian walloping at Austerlitz came in after the invitations had already been sent out. The Muscovites, of course, “felt that something was wrong, and that to discuss this bad news was difficult,” but the party, they decided, must go on (306). And so they persist in their charade, basking in the illusory glow of triumph, much the way a recently broke businessman might show up to work in the same shiny Lexus and wearing those same golden cufflinks. And oh, the yarns those high-fiving Muscovites do spin about Austerlitz: “This one had saved a standard, that one had killed five Frenchmen, that one had loaded five cannons single-handed” (307). Of Prince Andrei, whom they assume to be dead, nothing is said.

Yet if you ask any ordinary Russian today what exactly happened at the battle of Austerlitz, most would be hard-pressed to remember much of anything about that military campaign, except for one little thing: that stirring moment in War and Peace when Tolstoy’s hero has that powerful epiphany while gazing wounded up at the glorious sky. Such is the power of Tolstoy’s art, not to mention the accuracy of his insight. Our greatest and most enduring personal triumphs, Tolstoy observes, are seldom the ones described in the headlines or the history books. They don’t appear on the scoreboards or in our public celebrations. More often than not, they are those transformative moments we experience in the quiet inwardness of our souls when the cameras are turned off and nobody is watching. Except for God, that is—and Tolstoy.

![]()

Many of Tolstoy’s contemporaries missed the point completely. In his essay “The Old Gentry,” published in 1868, the influential literary critic and revolutionary activist Dmitry Pisarev perceived a real lesson about success in the character of Prince Boris Drubetskoi, son of an impoverished nobleman who, with the assistance of a relentless mother, claws his way to professional and social prominence. Pisarev considered Boris an exemplar of the then popular philosophy of “rational egoism,” which posited that when strong, pragmatic individuals pursue their self-interest without constraints, society as a whole benefits. Boris, apparently, is a tough, clear-eyed realist who sees how the world actually works, in contrast to, say, his dreamy and impetuous childhood friend, Nikolai Rostov:

The essential difference between these two young men is apparent from the moment they step out into the world. . . . Boris seeks for solid and tangible benefits. Rostov wants more than anything, and come what may, bustle, glamour, strong sensations, effective scenes and bright pictures.

The problem is that, like most agenda-driven literary critics of his time, Pisarev was, well, a rather bad reader of Tolstoy. With his impulsiveness and idealism, Nikolai, of course, is the far more attractive character in Tolstoy’s world. He believes in intangible, useless things like beauty and honor and sacrifice for a cause greater than himself. Whereas all Boris believes in, more often than not, is . . . Boris.

Oh, and this highly productive careerist, Tolstoy would have us notice, doesn’t actually produce anything. He rises to a position of power not because of any distinctive qualities of imagination or courage or even productivity, but because of his “skill in dealing with those who give rewards for service—and he was often surprised at his quick success and at how others could fail to understand it. . . . He made friends and sought acquaintances only with people who were above him and therefore could be of use to him” (365). Such impressive skill does indeed demonstrate Boris’s powers of observation—not to mention his blindness to life’s deeper purpose. This young man, bemused by the apparent naïveté of his less pragmatic peers, is, contrary to Pisarev’s reading, shown to be a rather odd specimen of humanity with a comically deformed worldview.

This becomes all the more apparent as we observe the parallel unfolding of the lives of these two friends. After his gambling fiasco, Nikolai is determined to pay back the debt to his parents in five years. All he wants to do, understandably, is return to the army, where “there were none of those unclear and undefined money relations with his father; there was no recollection of that terrible loss to Dolokhov! Here in the regiment everything was clear and simple” (395).

It would be nice, certainly, if that were in fact the case. But it would not be Tolstoy. Shortly after returning, Nikolai discovers that his regiment commander and friend, Major Vassily Denisov, is facing possible court-martial for having seized a transport of food to feed his hungry regiment, who had been denied provisions for two weeks. Determined to rectify this injustice, Nikolai first visits Denisov in the military hospital, where the older man is recovering from a slight injury while awaiting the decision regarding his case. There, amid the stench of dead flesh and the sight of pallid faces attached to mangled, bleeding bodies, Nikolai resolves to deliver a petition on his friend’s behalf directly to the tsar himself in the Prussian town of Tilsit, where Alexander and Napoleon are about to sign a truce. What is this? wonders Nikolai. So many Russians wounded and dead, and suddenly Alexander I and the enemy, a self-styled emperor of negligible antecedents, are friends?

As it happens, Boris is also present at that significant event, although for entirely different reasons: “[F]or a man who valued his success in the service to be in Tilsit at the time of the emperor’s meeting was a very important matter, and Boris, having gone to Tilsit, felt that from then on his position was completely assured” (408). Needless to say, the unflappable Boris is no more bothered by a wronged comrade than he is by a troubling truce; in fact, he uses this turn of events as a networking opportunity for himself, hosting one of Napoleon’s adjutants in his quarters and even having several French officers over for a nice supper!

When Nikolai shows up at his friend’s doorstep just as the table has been laid, Boris receives him coldly, clearly embarrassed by this mere hussar in civilian clothing who threatens to upset his otherwise smoothly running social affair. Immediately noticing the annoyance in Boris’s face, Nikolai is at the same time “oddly struck in Boris’s apartment by the sight of French officers in those same uniforms which he was used to looking at quite differently from the flank line” (408). The fiery young Russian patriot, you see, still wants to pump bullets into those enemy soldiers, whereas Boris would rather fill their tummies with wine and caviar, the better to advance his own career interests. When Nikolai requests Boris’s assistance in getting the petition to the tsar, the latter, “crossing his legs, and stroking the slender fingers of his right hand with his left, listened to Rostov the way a general listens to the report of a subordinate, now looking away, now looking directly into Rostov’s eyes with the same veiled gaze” (409).

In his final appearance in the novel, many hundreds of pages later, Boris can be seen speaking with a different childhood friend, Pierre Bezukhov, whom Boris has run into just before the battle of Borodino. Using this chat on the eve of what many fear will be a horrific affair as another career advancement opportunity, Boris waxes eloquent about Russian heroism just loudly enough so that Kutuzov, standing nearby, will notice him. Boris does, in fact, very briefly get Kutuzov’s attention, and that’s the last we ever see or hear of him. In all my years of teaching War and Peace, I’ve met few readers who are bothered by or even notice his sudden disappearance from the novel, ending up where such people often end up in life: forgotten. The ever-perspicacious Natasha, reminiscing with Sonya much earlier, senses Boris’s fate from the beginning: “ ‘I don’t remember [Boris] the way I do Nikolai. I close my eyes, and I remember him, but Boris I don’t’ ” (she closed her eyes), “ ‘no—nothing’ ” (235).

Now, just to clarify: Boris is no evil monster. Indeed, this complex, full-blooded character is sufficiently charming not only to attract Pierre, but to make the (very) young Natasha fall in love with him. Moreover, Tolstoy reminds us, it is life circumstances that have made Boris into who he is: “ ‘It’s all right for [Nikolai] Rostov, whose father sends him ten thousand rubles at a time to talk about how he doesn’t want to bow to anybody or be anybody’s lackey,’ ” Boris muses at one point. “ ‘[B]ut I, who have nothing except my own head, must make my career and not let chances slip, but avail myself of them’ ” (248). Okay, the guy’s got a point: so much easier to be the proud, principled aristocrat when the cost of doing so isn’t your financial security.

But, then, Nikolai is hardly blind to life’s harsh realities. He knows that the world can be a frightening place—a place in which so-called friends let friends gamble drunk and then take their money, a place in which noble intentions are rewarded with a slap in the face, and ideals routinely besmirched, if not shattered. In such a world, Boris’s self-focused, steely-eyed pragmatism might seem the wiser course. True, Boris will never know Nikolai’s painful confusion as he watches everything he values come tumbling down at Tilsit, or Andrei’s bewilderment as he looks up at the sky at Austerlitz and realizes that his dreams of glory have been nothing more than an illusion.

Nor will Boris experience the deeper satisfaction of a life courageously and authentically lived. For while the turbulence of historical change eventually sweeps him into the dustbin of irrelevancy, Nikolai and Prince Andrei continue to evolve, their road to self-discovery paved with the shards of one broken ideal after another. Trudging through that debris with an open mind and a searching heart will both strengthen and deepen them, just as Tolstoy believed that the hardship of those troubled years was good for Russia itself. “If the cause of our victory was not accidental, but lay in the essence of the character of the Russian people and army,” he wrote in a draft of an introduction to the novel, “then that character must be expressed still more clearly in the period of failures and defeats.”

One character intimately familiar with such failures and defeats is the tiny, stooping Captain Tushin, a poorly paid artillery captain who is no stranger to the injustices of nineteenth-century life. During battle this slight, unwashed man desperately tries to save his undersupplied, undefended battery from a merciless pounding by enemy fire. Adding insult to injury, he is later publicly chastised for defying orders to evacuate his position by General Bagration, the very man whose failure of leadership placed Tushin’s battery in that predicament in the first place. Yet Tushin manages to find a deeper purpose in his bloody, thankless work, never descending to the level of bureaucratic sycophancy. On the contrary, it is in the thick of battle that he seems to come most alive.

Even as his battery is getting pummeled by the French, he can be seen barking out commands to his soldiers and running from cannon to cannon with the childlike enthusiasm of someone who loves what he does. In order to preserve his own sanity in this rather dire situation, he has created an imaginary world for himself: The enemy cannons in the distance are but little pipes from which an invisible smoker released occasional puffs of smoke, while his own firing guns are old friends needing a few words of encouragement. As for Captain Tushin himself, he is a mighty man, flinging cannonballs at the French with both hands. In other words, he turns an unpleasant job he neither chose nor may leave into a daring game that offers fulfillment and even a little fun into the bargain. No wonder Prince Andrei, upon first meeting Tushin before the battle of Schöngrabern, senses “something special” in this otherwise ordinary, even slightly comical, little man.

Tolstoy is not asking us to pretend we don’t live in the real world, with its many responsibilities, challenges, and financial necessities. Nor is he saying that we should quit our jobs, pack our bags, and head to a mountaintop in Siberia, or to a monastery, for that matter. Anybody with enough drive to produce ninety volumes’ worth of novels, novellas, short stories, plays, essays, letters, and diaries, after all, is hardly an exemplar of monastic self-abnegation. Tolstoy loved work; he believed in the value of it. One of the most famous scenes in Anna Karenina is that joyous one in which Levin, exhausted and dripping with sweat, swings his scythe for hours through the thick hay, right alongside his peasants. What concerns Tolstoy is our relationship to our work. Does it enrich us as human beings, or just our bank accounts? Does it connect us more deeply with the world, or rather cause us to hunker down in little bunkers of self-involvement? And when we find ourselves confronted with a less-than-ideal work environment, do we merely trade our large spirits for the smaller comforts of job security, or, like Captain Tushin, find some way to infuse the mundane madness of the workplace with the spark of our own inspiration?

Moreover, should our efforts fail to pan out in the end, as is so often the case, does it follow that our lives have been a waste? The multimillionaire father of a college acquaintance of mine must have thought so, for when he lost his savings in the stock market crash of 1987, he blew his brains out. To which Tolstoy would say: If your raison d’être is so wrapped up in “making it” that failure leaves you with a gaping hole inside (perhaps all too literally), then maybe you have been engaged in the wrong kind of work; maybe you have been wasting your life.

At some point or another, we, like Tolstoy’s characters, must face the truth that we are part of something greater than ourselves, prompting us to ask not “How do I get to the next rung on the ladder?” but “Is this the ladder I should be on in the first place? Is this the kind of life I want to lead?”

Good questions to ponder, for in such moments, Tolstoy says, we glimpse the kind of meaning to our existence that we almost always fail to see when caught up chasing the better job or the bigger house or the more beautiful plot of land. What that meaning is, each one of us must decide for him or herself. Sure, for some of us, at some times, it very well may involve donning a robe and a pair of bast sandals to trek seventy miles to the next monastery. But more often than not, if we look carefully enough, we will find what we are seeking right here, right now, on that bloody, beautiful battlefield known as everyday life.

I. kasha: buckwheat oatmeal.

II. kvass: Russian nonalcoholic beer made from fermenting rye or barley.