![]()

The closer we come to death, or rather, the more vividly we remember it . . . the more important becomes this single indispensable thing called life.

—Tolstoy’s letter to Vladimir Chertkov, August 1910

Tolstoy on his deathbed, Astapovo train station, 1910.

Few subjects are more integral to Tolstoy’s writing than death. It flows from the writer’s pen like an uncorked bottle of Russian vodka—depicted in every imaginable flavor, texture, and color. Whether a slow death in the bedroom or a sudden one on the battlefield, an ignominious death by suicide or state-sponsored death through public execution, dying is a topic on which he dwells attentively and with no small fascination. But then, Tolstoy had considerable personal experience with mortality. He’d lost both parents by the age of nine. He witnessed wartime slaughter while serving as a soldier in the Caucasus and in the Crimea. In 1856 his brother Dmitry died of consumption, and in 1860 another brother, Nikolai, died of the same disease. For weeks after his soul-wrenching panic attack during that land-buying trip in 1869, Tolstoy was himself on the verge of suicide. He lost five of his young children either to disease or complications in childbirth. In fact, after the death of one of them, Petya, in 1873, he fled his estate for Moscow out of fear that he, too, might catch death as one would a cold. Given all his familiarity with the topic, can it be any wonder that Tolstoy penned what is surely the most bloodcurdling death journey in world literature? There is a reason Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) is still read in medical schools today, where it teaches doctors in training exactly what dying looks, smells, and feels like, in all its grim detail.

Yet this writer who affirmed in What I Believe (1884) that “death, death, death, attends us every second” found it extremely difficult to deal with the reality of death in his own life. “Yesterday a soldier was found hanged in the Zaseka wood,” he wrote years earlier in his diary in 1856, at twenty-seven, “and I rode round to have a look at him.” Not before taking time to muse about the prettiness of the forester’s wife, however, or seriously considering whether to order a soldier to bring him an attractive young woman. A few weeks later, awakening to the news that a peasant had drowned in his pond, the count was in no rush to respond: “Two hours have gone by and I’ve done nothing about it.”

Stranger still is his response to the news in 1856 that his brother Dmitry was dying. “I was particularly loathsome at the time,” Tolstoy would later write in his Recollections. “I had come from Petersburg, where I was very active in society, and I was bursting with conceit! I felt sorry for [Dmitry], but not very. I simply put in an appearance at Orel and left immediately.” He even admits to being rather annoyed that the whole affair made him miss a performance at Court to which he’d been invited. Three weeks later he received the news that Dmitry had died. He didn’t go to the funeral, however, because of a prior social commitment.

Four years later Tolstoy had another chance to get it right when he learned that another brother, Nikolai, lay dying in Soden, Germany. On this occasion he did manage to pull himself away from his travels through Europe long enough to accompany his brother and their sister Marya and her three children to the south of France, where Nikolai died a month later. “Terrible though it is,” Tolstoy wrote to his surviving brother Sergei, “I am glad it all happened before my eyes and affected me as it should have done. It is not like the death of [Dmitry], which I learned of at a time when my mind was completely taken up with other things.” Still, as Tolstoy would admit in a long, heartfelt letter to his friend Afanasy Fet, Nikolai’s death shook him to the core:

Nothing in life has made such an impression on me. [Nikolai] was telling the truth when he said there is nothing worse than death. And if you really think that death is after all the end of everything, then there’s nothing worse than life either. What’s the point of struggling and trying, if nothing remains of what used to be [Nikolai] Tolstoy? . . . What’s the point of everything, when tomorrow the torments of death will begin, with all the abomination of meanness, lies, and self-deceit, and end in nothingness, in the annihilation of the self. An amusing trick! Be useful, be virtuous, be happy while you’re alive, people have said to each other for centuries—we as well—and happiness and virtue and usefulness are truth; but the truth that I’ve taken away from my 32 years is that the situation in which someone has placed us is the most terrible fraud and crime for which words have failed us. . . . So that when you see it clearly and truly, you come to, and say with horror like my brother: “What does it all mean?”

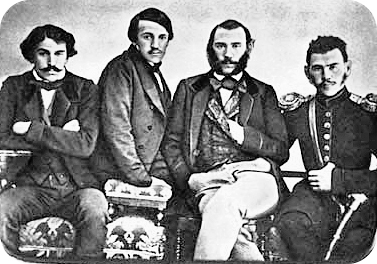

Tolstoy with his brothers in 1854. From left: Sergei, Nikolai, Dmitry, Tolstoy on far right.

What does it all mean? Now, there’s a question Tolstoy would certainly return to over and over again throughout his lifetime. “Why should I live?” the writer would ask, some two decades later, in his Confession. “Why should I wish for anything or do anything? Or to put it still differently: Is there any meaning in my life that will not be destroyed by my inevitably approaching death?” One of his most earnest attempts to answer these questions came in the tract “On Life,” the essay that would have such a profound effect on the young Ernest Crosby. Written in 1887, when Tolstoy was nearly sixty, the work argues that death as we know and fear it doesn’t actually exist; we only think it does, because we have the wrong view of reality. Most of us take as real those things we can see and touch, including our own physical selves. But true life, he argues, begins when we acknowledge our connection to an eternal spiritual whole, which existed long before we arrived in this world and will exist long after we’re gone. If we don’t voluntarily accept this more accurate view of reality, then it will be forced upon us surely enough at the time of our physical death, at which too-late point it is certain to cause us unnecessary suffering. Only “by renouncing what is perishing and must perish—that is to say, our animal personality—can we obtain our true life which does not and cannot perish.”

Yet surely this exceptionally vital man who fathered thirteen children—who on multiple occasions in his sixties and seventies trekked 125 miles by foot from Moscow to Yasnaya Polyana, who rode horseback in his eighties, who tossed his grandchildren up in the air and then caught them with one hand—surely this man didn’t really believe that the body was an illusion, did he? Surely this writer who with his own eyes saw corpses lying in blood-drenched battlefields, watched a brother die in his arms, and described death as vividly as anyone ever managed to—surely he did not believe that death is a mere figment of an unenlightened imagination?

The writer Maxim Gorky, for one, wasn’t buying these arguments, and went so far as to accuse the bearded sage of not a little hypocrisy. “Although I admire him,” the young Gorky wrote, “I do not like him. He is exaggeratedly preoccupied, he sees nothing and knows nothing outside himself. . . . He lowers himself in my eyes by his fear of death and his pitiful flirtation with it; as a rabid individualist, it gives him a sort of illusion of immortality.” Gorky’s characteristically incisive remarks expose an aspect of Tolstoy’s personality that has long troubled even his most ardent admirers, myself included: the nearly pathological obsession with death that seems as out of step with his exceedingly vital nature as it does with the selflessly life-affirming message of his greatest novel.

But then, maybe there’s not such a contradiction, after all. For pretty much his whole life, Tolstoy had searched for a justification of life in the face of death—for a way of living, in other words, “so that death cannot destroy our life,” as he puts it in What I Believe. Yet if the later sage achieves this goal simply by rendering death irrelevant, then the author of War and Peace, struggling with the same issues decades earlier, takes a different approach: he urges us to fully embrace our finitude, precisely in order to enhance our engagement with the things of this world, and to deepen our appreciation of the short time we’ve been allotted in it. In War and Peace, nothing lights a fire in a person’s belly more than an awareness that one day in the not-too-distant future that belly will be filled not with caviar and cream puffs, but maggots and dirt. Not only do things of this world inevitably start looking and smelling and tasting better, but some characters learn to start living as if they were dying, which, as Tolstoy reminds us, we all are, however slowly, every minute of every day.

Early in the novel, when young Nikolai Rostov believes he is about to be popped off by attacking French soldiers, his first thought is about what a nice thing it is to be alive. He looks upon the glistening blue waters of the Danube, the glorious sky, the pine forests bathed in mist, and is suddenly struck by

[h]ow good the sky seemed, how blue, calm, and deep! How bright and solemn the setting sun! How tenderly and lustrously glistened the waters of the distant Danube! [ . . . ] And his fear of death and the stretcher, and his love of the sun and life—all merged into one painfully disturbing impression. (148)

Hundreds of pages later, at the battle of Borodino, the usually aloof Prince Andrei discovers that even reeking wormwood smells pretty good when your head is about to be lopped off by an exploding grenade:

“Can this be death?” thought Prince Andrei, gazing with completely new, envious eyes at the grass, at the wormwood, and at the little stream of smoke curling up from the spinning black ball. “I can’t, I don’t want to die, I love life, I love this grass, the earth, the air . . .” (810–11)

Are you noticing a pattern? Were the author of War and Peace alive today, he might be grateful enough for advanced methods of dampening the physical pain of dying, but we can safely guess that he wouldn’t be jumping on the cryonics bandwagon. Because when you take away a human being’s consciousness of dying, you also take away his capacity for living. The problem, Tolstoy would say, is that most of us don’t do either one particularly well.

In my classes and workshops about The Death of Ivan Ilyich I ask participants to imagine that they have six months to live: How would they spend their time? Most participants find it all but impossible to respond honestly. Many just nervously giggle or tune out entirely, while not a few say what they think someone with six months to live would or should say. For the most part, this remains a purely hypothetical exercise, leading one to conclude that most of us have plenty of ideas and stereotypes about death, but find it extremely difficult to make it real to ourselves.

Now, there might be some good reasons for this. It could well be the case that we human beings are hardwired not to dwell too much on the fact of our own extinction. Doing so, after all, can put us in the position of soldiers who die in battle not from gunshot wounds but from the fear of being killed that causes them to seize up, to make fatal mistakes, to give up. Tolstoy’s own fear of death several times led him to the brink of suicide. Yet, as the residents at Beaumont Juvenile Correctional Center in Virginia (where my students and I discuss Ivan as part of my class “Books Behind Bars: Life, Literature, and Leadership”) insist, not thinking about death can be no less frightening or debilitating: Pushing death out of their minds, they explain with astonishing candor and insight, is one technique they employ for protecting themselves emotionally amid the violence that is a regular part of their lives. And yet what such screens have done in the end, they confess, is to make it a bit too convenient for them to avoid asking the hard questions about their behavior and their lives that need to be asked.

It is gratifying to an extreme to see how Tolstoy’s tale about a man who comes alive only when he realizes he’s dying inspires these young men of seventeen to twenty to open up to my students and me about people they’ve watched die, mistakes they’ve made, opportunities they’ve squandered, or perhaps never had in the first place. Inevitably, it makes all of us feel a little more connected as human beings, reinforcing my conviction that Tolstoy is perhaps the most universal of all the great Russian writers, and death his most accessible theme.

Now, War and Peace isn’t nearly so compact a parable as this later work. Still, it too is wise about death in the same sort of direct, jolting way. Most of us don’t like to think about death, Tolstoy shows us on this much larger canvas, and with all of the delights life has to offer, maybe there’s no need to overdo it. Still, at some visceral level we get it, and Tolstoy gets that we get it: death, like sex and war, is here to stay, and we, alas, are anything but. So if we want to make our short life on this earth count, we’d best come to terms with that fact. Or, as Tolstoy would put it in What I Believe: “Life is life, and we must use it as best we can.”

Indeed, the sad truth about the most tragic character in War and Peace, Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, is that he ultimately fails to embrace this wisdom. Like his sudden transformation while lying wounded at Austerlitz, chatting with Pierre on the ferry raft, or encountering that dark-haired, slender girl at Otradnoe, Andrei’s passionate love of life on the battlefield of Borodino lasts only briefly—for all of about two seconds. No sooner does he think about how much he loves the grass, the earth, and the air, than he “remembered that he was being looked at” (811). And so, rather than hitting the dirt like the other officers, he just stands there, undecided, watching the spinning shell about to explode in his face. And he says to the adjutant: “ ‘Shame on you, officer!’ ” (811). For what? For trying to save his own life? This man who is so concerned about what the world will think of him, thinks himself right out of making a spontaneous, potentially lifesaving decision. But then, this isn’t terribly surprising in someone who, on the evening before battle, has already concluded that his entire life has been one long, cruel illusion:

The whole of life presented itself to him as a magic lantern, into which he had long been looking through a glass and in artificial light. Now he suddenly saw these badly daubed pictures without a glass, in bright daylight. “Yes, yes, there they are, those false images that excited and delighted and tormented me,” he said to himself, turning over in his imagination the main pictures of his magic lantern of life, looking at them now in that cold, white daylight—the clear notion of death. “There they are, those crudely daubed figures, which had presented themselves as something beautiful and mysterious. Glory, the general good, the love of a woman, the fatherland itself—how grand those pictures seemed to me, how filled with deep meaning! And it’s all so simple, pale, and crude in the cold, white light of the morning that I feel is dawning for me.” (769)

Anybody who has gone through the dark night of the soul knows exactly what Andrei is feeling here, but if you’ve come through to the other side, you know something else, too—something conspicuously absent from Andrei’s analysis of the way things are: yes, life is full of deception and pain and disappointment, but it has beauty and magic and meaning, as well. These Prince Andrei can no longer see, precisely because he has seen—or rather, thinks he has seen—too much. “ ‘Ah, dear heart, lately it’s become hard for me to live,’ ” he confesses that same evening to Pierre, who has come to the front to witness the upcoming battle. “ ‘I see that I’ve begun to understand too much. And it’s not good for a man to taste of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil . . . Well, it won’t be for long!’ he added” (776). Indeed, his premonition proves right.

After the stopover in Mytyshchi, Andrei travels with the Rostovs some 125 miles east to Yaroslavl, away from advancing French troops, and is offered refuge in the house of a town merchant. By this point, he

not only knew that he would die, but felt that he was dying, that he was already half dead. He experienced an awareness of estrangement from everything earthly and a joyful and strange lightness of being. Without haste or worry, he waited for what lay ahead of him. The dread, the eternal, the unknown and far off, of which he had never ceased to feel the presence throughout his life, was now close to him and—by that strange lightness of being he experienced—almost comprehensible and palpable. (982)

As he lies there, mentally reviewing the past few weeks of his life, Andrei remembers Anatole in the operating tent, and is tormented by the question of whether the young cad is even still alive. (Tolstoy doesn’t answer this question for the reader: after his leg is amputated, we never hear of Anatole again.) And then Andrei recalls his recent, inexplicable surge of love for Natasha in Mytyshchi; but that too has been transformed into something like bitter regret. Can it be, he now wonders, that fate has once again brought them together, only so that he should now die? That “ ‘the truth of life has been revealed to me so that I should live in a lie? I love her more than anything in the world. But what am I to do if I love her?’ he said and suddenly moaned involuntarily, by a habit acquired during his sufferings” (983). Even if he really wanted to do something about his love for Natasha (and it’s no clearer here than elsewhere in the novel that he does), there’s not much he can do, and it is precisely this sense of powerlessness in the face of the radical unknown that pains him most.

Princess Marya, meanwhile, gets the news of her brother’s grave condition and whereabouts. Taking Andrei’s seven-year-old son, Nikolenka, with her, she braves the treacherous roads to be with him. The first person she meets upon her arrival in Yaroslavl is Natasha, who has been at Andrei’s side for weeks, and whom the princess hasn’t seen since their chilly meeting in Moscow long ago, when Natasha and Andrei were first engaged. But it takes Marya just one glance into the eyes of that flighty young girl who repelled her two years ago to see “a sincere companion in grief, and therefore her friend” (977). For her part, Natasha, looking into Marya’s luminous eyes, which seem to penetrate into her very soul, feels an immediate closeness to this woman who once appeared so strange and distant. Natasha’s lips begin to tremble, ugly wrinkles begin to form around her mouth, and, without saying a word, she bursts into sobs and covers her face. “Princess Marya understood everything” (978).

Well, almost. In her imagination, Marya sees the gentle face of her dear brother Andryusha, which she remembers so well from childhood, and, preparing herself to be moved by the tender words he will certainly speak to her, she enters the room. What she finds is a man she hardly recognizes:

In his words, in his tone, especially in that gaze—a cold, almost hostile gaze—there could be felt an alienation from everything of this world that was frightening in a living man. He clearly had difficulty now in understanding anything living; but at the same time it could be felt that he did not understand the living, not because he lacked the power of understanding, but because he understood something else, such as the living could not understand, and which absorbed him entirely. (979)

Clearly, Andrei is going through what psychologists sometimes refer to as decathexis, or a letting go, a withdrawal from earthly attachments that accompanies the acceptance of death. But withdrawal isn’t necessarily the same thing as wisdom, and just what exactly that “something else” Andrei now understands is, Tolstoy never tells us. Still, that hasn’t stopped scholars and readers alike from assuming that Tolstoy intends to show here how Andrei has indeed attained a wisdom to live by, often citing as evidence Andrei’s poignant musings about love in these delirious final hours:

“Love? What is love?” he thought. “Love hinders death. Love is life. Everything, everything I understand, I understand only because I love. Everything is, everything exists, only because I love. Everything is connected only by that. Love is God, and to die—means that I, a part of love, return to the common and eternal source.” (984)

Yet as touching as Andrei’s reflections are—painfully close as they are to the very heart of the matter—they are for Andrei just thoughts. True, these words echo Tolstoy’s own argument in “On Life,” and the principle the dying man articulates is fundamental to many spiritual traditions, including Buddhism and Hinduism, both of which deeply influenced the author. Yet, when placed on Andrei’s cold, parched lips, half animated by that hostile gaze, his reflections about love and the eternal life seem . . . only detached, distant. Even he senses it: “These thoughts seemed comforting to him. But . . . [s]omething was lacking in them, there was something one-sidedly personal, cerebral” (984). Quite right: How could it be otherwise, really? What the dying prince says about love is beautiful; how he has actually expressed that love, though, whether here or elsewhere in the novel, is anything but.

Critic George Steiner has argued that there are a number of scenes in War and Peace, such as this one, in which Tolstoy “conveyed a psychological truth through a rhetorical, external statement, or by putting in the minds of his characters a train of thought which impresses one as prematurely didactic.” Steiner’s observation is accurate enough, but his attribution, less so: the philosophical abstraction in this moment belongs not to Tolstoy, but Andrei. For the author knows what we know: Andrei’s failure to connect on a visceral, emotional level with the world around him while dying is more than a matter of decathexis; it is also a natural reflection of how he’s lived his entire life.

“ ‘Yes, this must seem pitiful to them!’ ” Andrei thinks. “ ‘Yet it’s so simple!’ ” (981). And, gathering up his strength, he tries to recall a line from the Gospels, only to conclude that Princess Marya and Natasha will understand it in their own way. So he remains silent, thinking: “ ‘This they cannot understand, that all these feelings they value, all these thoughts of ours, which seem so important to us—that they’re unnecessary’ ” (981).

At one level, of course, he’s right. So many of the things we do and value in this world, when illuminated by that cold, white light of death, are unnecessary. But it isn’t just our worldly ambitions and strivings Andrei has in mind, as on the evening before the battle of Borodino. No, he is also referring to those “silly” little things Princess Marya does in this moment to comfort him, as well as herself—like suggesting, for instance, that she bring in his son Nikolenka; to which Andrei responds, with a “smile not of joy, not of tenderness for his son, but of quiet, mild mockery of Princess Marya, who, in his opinion, was using her last means to bring him to his senses” (980). Marya is horrified, and can we blame her? What she wants is for her brother to affirm his kinship by seeing his very own, only son—by connecting with him, recognizing him, and giving him his fatherly blessing before his death. That Andrei cannot comprehend this, and is even mildly contemptuous of his sister’s efforts, is proof, as Marya rightly surmises, of “how terribly far he now was from everything living” (980). Andrei is still denying his primal connection to the living, and worse, he is mocking the need for a comforting ritual by those who watch him die.

As I write this, I catch myself glancing out into the yard. There is the oak tree beneath which my kitten Monkey lies buried. I recall those many hours my wife Corinne and I spent choosing that very spot, with just the right balance of sunlight and shade; those countless vet visits and thousands of dollars paid to specialists to see if there was something, anything, we could do to cure his congenital illness; that assortment of wooden caskets I considered, wanting to make sure my little guy was buried in just the right one. I’ve even kept letters I wrote to him after his death, asking forgiveness for our failure to be at his side when he died—quite unexpectedly, of a different disease we never even knew he had (on our honeymoon, no less). I can only imagine how pathetic all this would have appeared to someone like Prince Andrei, not least when such mawkish attention was being lavished on a mere pet. But to me these “ridiculous” actions were absolutely necessary, just as everything Princess Marya and Natasha do in the days leading up to Andrei’s death are necessary for them.

“What a jerk!” blurts out one of my students during a discussion of this scene. “Look at how he treats his own sister on his deathbed!”

“Yes, do look, but don’t . . . judge,” I respond with uncharacteristic forcefulness, as if I need to defend the guy. “How, after all, are we supposed to treat others when we’re dying?” I ask. “Where are the guidebooks informing us about such things?”

The fact is, Tolstoy takes us completely out of the realm of right and wrong in this scene—beyond the reach of pat answers—and puts us instead face-to-face with life’s deepest mysteries. Tolstoy’s contemporaries, raised on romantic literary fare, would have been used to deathbed scenes filled with fulsome professions of love, tender tours down memory lane, maybe even a bit of hysterical wailing. But Tolstoy gives us none of that. No, he is here to tell all of us that death is never what we think it is, neither for the person dying nor the people witnessing it. Death, like life itself, is infinitely more surprising and mysterious than our rational mind may ever fathom. Look at it, Tolstoy says, get curious about it. Be with it, and then be quiet, like Princess Marya and Natasha, who, in Andrei’s final hours, “did not weep, did not shudder, . . . [and] also never spoke of him between themselves. They felt that they could not express what they understood in words” (985).

![]()

In 1865, a few years into the writing of War and Peace, Tolstoy “needed a brilliant young man to die at Austerlitz,” but then changed his mind, deciding that this son of old Prince Bolkonsky was only to be wounded, since he was needed for later on. For what purpose Tolstoy never did say, but having followed the character to the end of his journey, perhaps we now know. You see, Tolstoy needed Andrei Bolkonsky to illustrate the fate of a man who never quite learns how to integrate his high ideals with ordinary reality, who never learns how to allow his genuine insight into that greater something out there to deepen his appreciation of this messy world down here.

There is a telling moment much earlier in the novel in which Andrei, who has just begun to court Natasha, is so moved by her singing he finds himself on the verge of tears over “a sudden, vivid awareness of the terrible opposition between something infinitely great that was in him, and something narrow and fleshly that he himself, and even she, was. This opposition tormented him and gladdened him while she sang” (467). This same opposition continues to torment and, in an odd way, gladden him throughout the novel, right up until his end, as he slips quietly into eternity, something he appears to have been prepared to do for quite some time. What Tolstoy gives us in Prince Andrei is the portrait of a man, not yet thirty-five years old, who has made his peace with death, rather than life.

And yet, with the possible exception of Hadji-Murat, I know of no other character in all of Tolstoy’s fiction or elsewhere in Russian literature whose death is described with such tragic beauty. Anna Karenina’s famous death is just plain gruesome, and even Ivan Ilyich’s end, for all its trenchant physical and psychological detail, doesn’t reach the poetic heights to which Tolstoy takes us in these pages. And this is the case, I would argue, not just because Tolstoy was capable of the same as a writer, but because Andrei’s complexity and depth as a human being called for such treatment in this book.

For all his massive failings—perhaps even because of them—Prince Andrei is nevertheless attuned to some higher dimension of experience that eludes most other characters. In early drafts of the novel, before there was any Andrei, there was Boris Drubetskoi, who was endowed with many of the features of the character who would become Andrei. Early on these two characters were conflated in Tolstoy’s imagination, but all that later changed in an important and telling way. Although Andrei would continue to share with Boris the traits of egoism and ambition in the final version of the novel, Andrei’s fatal flaw—an inability to come to terms with the world as it is—stems from a far deeper engagement with life than Boris ever musters; the latter is unable even to recognize, let alone grapple with, the sorts of existential questions that haunt Andrei throughout. From the shell of one of the novel’s major careerists, then, emerged one of Russian literature’s great and tragic seekers.

Nowhere is his tragic depth more poignantly captured perhaps than in the description of Andrei’s dream, our last encounter with him in the novel. In the prince’s dream he is lying in the very same room he happens to be in. There are all sorts of people there, and he argues with them about “something unnecessary.” They are preparing to go somewhere, but Andrei “recalls that it is all insignificant and that he has other, more important concerns.” Not that this stops him from engaging the group, to everybody’s surprise, “speaking some sort of empty, witty words” (984). Sound familiar? This is the Andrei we met at the beginning of the novel, bored to death by everyone and everything at Anna Pavlovna’s soiree, balking at the fakeness all around him, and yet carrying on as sure-footedly as anyone there. This brilliant young aristocrat was about to embark on an exceptional career—one he hoped would win him the admiration of the very high society he so despised.

But then Austerlitz happened; so, too, something happens in the dream:

Gradually, imperceptibly, all these people begin to disappear, and everything is replaced by the question of the closed door. He gets up and goes to the door to slide the bolt and lock it. Everything depends on whether he does or does not manage to lock the door, but still, he painfully strains all his force. And a tormenting fear seizes him. And this fear is the fear of death: it is standing behind the door. But as he is crawling strengthlessly and awkwardly towards the door, this terrible something is already pushing against it from the other side, forcing it. Something inhuman—death—is forcing the door, and he has to hold it shut. He lays hold of the door, strains in a last effort—to lock it is already impossible—just to hold it shut; but his attempts are weak, clumsy, and pushed by the terrible thing, the door keeps opening and shutting again.

Once more it pushes from the other side. His last supernatural efforts are in vain, and the two halves open noiselessly. It comes in, and it is death. And Prince Andrei died.

But in the same instant that he died, Prince Andrei remembered that he was asleep, and . . . he made an effort within himself and woke up. (984–85)

If you’ve been reading War and Peace carefully, you may recall that Tolstoy uses an identical image several hundred pages earlier, when Andrei comes home on that snowy March night and finds his wife Liza going into labor. After being instructed to wait in an adjacent room, he covers his face while listening in bewilderment to the shrieking, animal moans coming from the other side of the door. “Prince Andrei got up, went to the door, and wanted to open it. Someone was holding the door” (327). Now, it’s impossible to say with any certainty whether Tolstoy had recently reread this scene, written some three years earlier, while composing Andrei’s deathbed scene, but this much is clear: whether consciously or subliminally, the two moments are in the writer’s mind connected—so much so that the later sentence “He gets up and goes to the door to slide the bolt and lock it” is not just a nearly exact echo of the earlier one, but a rather neat reversal—“Prince Andrei got up, went to the door, and wanted to open it.” What are we to make of this?

Taken together, these two moments may be seen to embody the core of Andrei’s character, and the essence of his spiritual journey: he has always sensed there must be something on the other side of that proverbial door—something as attractive to him as it is repellent. He wanted to be in the room, after all, from which those animal-like moans were coming, where Liza was busy creating new life. Little did he know at the time that death, too, was lurking behind the closed door in that very moment; Liza, recall, died during childbirth. Now, hundreds of pages later, Tolstoy craftily realizes the metaphor, when that “[s]omething inhuman—death” finally breaks through, the door swings open and closed, and all separation between what’s on this side of it and what’s on that one is eradicated. It is there. It is here. It is everywhere. At once radically strange yet completely ordinary, death, like life itself, is happening all around him. Only now, for perhaps the very first time, Andrei truly sees and understands:

“Yes, that was death. I died—I woke up. Yes, death is an awakening.” Clarity suddenly came to his soul, and the curtain that until then had concealed the unknown was raised before his inner gaze. He felt the release of a force that previously had been as if bound in him and that strange lightness which from then on did not leave him. (985)

At the funeral a few days later, the onlookers go up to the clothed, washed body lying in the coffin and bid it farewell, each one weeping for different reasons: young Nikolenka, Andrei’s son, from the confusion in his heart; Countess Rostova and Sonya, out of pity for Natasha; and the old Count Rostov, because he knows that “soon he, too, would have to take that dreadful step” (986). Tolstoy’s own perspective in this moment is perhaps closest to that of Natasha and Princess Marya, who now allow themselves to weep, as well, though “they did not weep from their own personal grief; they wept from a reverent emotion that came over their souls before the awareness of the simple and solemn mystery of death that had been accomplished before them” (986).