2

2

2

2

Bily was at the stove carefully preparing the special complicated porridge he always made on this morning to fortify his brother and to keep himself busy so that he would not begin fretting before Zluty had even left the cottage. He was also finishing a pile of pancakes that were to be wrapped up in a woven cloth after they had cooled. They would serve as Zluty’s supper that night when he stopped to camp on the plain.

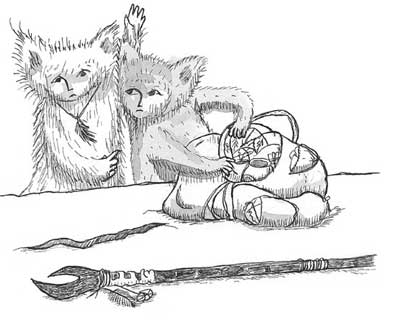

Zluty was packing all of the things he would need for the journey, and thinking about a certain small dark-blue berry he had noticed the previous year. It had been growing on a bush in one of the few shafts of sunlight that managed to penetrate the outer edge of the forest canopy. The birds that nested above had warned him that the berries were bad to eat, and so he had not bothered taking any. But a few nights earlier, Bily had been boiling feathergrass to concoct a new dye and sighing over the faintness of the blue colour it produced. Zluty, sanding the new walking staff he had made to take with him on his journey, had suddenly remembered the brightness of the blue berries and the richness of their colour and had made up his mind to bring some of them back as a surprise for Bily. He had already slipped an extra little pottery jar into his pack to hold the berries.

Zluty glanced above his bed at the beautiful hanging on the wall. Of all his possessions, he loved this best. The colours reminded him of the way the sunlight looked, filtering through the leaves in the Northern Forest. Bily had made it for his bed several years past and Zluty had loved it too much to allow it to be cut up for cleaning rags when Bily decided it was too thin and must be replaced. Zluty had insisted upon hanging it, and it looked so nice and unexpected on the wall that Bily had decided to make a special rug to hang above the long bench where they often sat and talked in the evenings when it was too warm for a fire.

The thought of his brother’s delight at having a new colour to use made Zluty want to laugh aloud, but he reminded himself that he must first test the berries to make sure the dye was good before he gave them as a gift.

‘I am going down to the digger mounds to see if they have milk,’ Bily called from the door. ‘Can you get the last pot of honey out of the cellar?’

‘I will just as soon as I have finished this,’ Zluty answered, grunting with the effort of tightening his pack. As he rolled the bedding so that he could bind it to the top of the pack it crackled loudly, for he had stuffed it with fresh sweetgrass the night before.

Bily came hurrying back inside and Zluty thought he must have forgotten the little wads of white fluff he traded to the diggers for milk, and which they used to soften their burrows. But his brother came straight over to him and said, ‘Oh, Zluty, come and see. It’s horrible!’

‘Is it one of the birds?’ Zluty asked. Many birds nested in the eaves of the cottage or in the bushes and small trees growing in the garden, and Bily appeared so upset that Zluty feared some harm must have come to Redwing, whom his brother dearly loved.

Bily caught hold of Zluty’s hand. ‘It is not any of the birds. It is the sky!’ He tugged his brother through the cottage and out onto the step. ‘Look!’ Bily insisted, pointing away to the West.

Zluty’s mouth fell open at the sight of a dark red stain spreading against the blue sky just above the horizon. It might have been a cloud saturated with the red dawn light, except it was in the West. He was alarmed, but a tiny part of him thrilled at the newness of it.

‘What does it mean?’ Bily asked. His frightened voice quenched the little spark of curiosity and excitement that had kindled in Zluty.

‘It is only a storm cloud,’ Zluty said in a reassuring voice.

‘But a storm cloud is not red,’ Bily objected.

He was right, Zluty thought, squinting his eyes at the stain. He said at last, with more certainty than he felt, ‘It is a mist. Mists are sometimes unusual colours, and it might simply have got that high by accident.’

Bily considered this, and then nodded slowly. ‘A mist could get confused,’ he said. ‘It might have got too high and now it does not know how to get back down to the ground.’

‘Exactly,’ said Zluty, relieved to see that his brother’s fluffed-up fur was beginning to settle. ‘If you are nervous, I can easily put off the journey to the Northern Forest for a few days.’

Bily looked horrified. ‘But you always go on the day after the first bellflower opens.’

Zluty saw then that in suggesting a change in their routine he had unsettled his brother even more than the queer sky, so he shook his head and pretended it had been a joke. ‘Of course I am going to go today,’ he said. ‘As soon as I have had my porridge.’

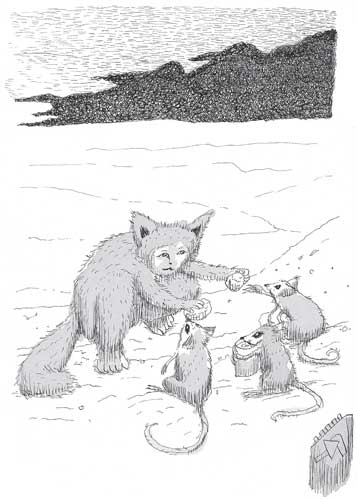

Bily gave a sudden cry and thrust the wads of fluff he had been carrying into his brother’s hand before running inside. Smiling, Zluty went down through the bushes and flowers and beyond the well to the flat dry ground where the diggers lived. He carefully avoided the holes in the ground where there was a single nest of poisonous blackclaws and came to the hump of earth, which was the entrance to the network of burrows and tunnels where the community of diggers dwelt. He stamped his foot three times then squatted down to wait. His smile faded as he studied the red stain just above the Western horizon. It didn’t really look much more like a mist than a storm cloud. But after all, what else could it be?

‘Ra!’ squeaked a voice, and Zluty turned his attention to the little digger that had emerged from the entrance to the hump. Zluty announced solemnly that he wished to trade for milk, and then he held out the wads that Bily had thrust into his hand. The digger twitched his shiny little black nose and crept forward to sniff suspiciously at the fluffs. At last he gave a soft ‘Ra’ and withdrew. Moments later, another two diggers appeared at the entrance. One of them carried a small misshapen mug of diggermilk.

The trade made, the diggers uttered polite squeaks of ‘Ra!’ before scurrying away with their prize. Getting to his feet carefully so as not to spill the milk, Zluty made his way back to the cottage. He regretted that he had not thought to point out the redness in the sky and ask the diggers what they made of it. Not that he would have learned much, for the little creatures had only a few words that meant many different things. Bily said the meaning was all in how those few words were said, but he spent more time with the diggers than Zluty because they liked to come and watch him when he was at the clay pit by the well, making pots.

‘I wish I knew how they make them,’ Bily said, skimming off the cream and then transferring the milk from the digger mugs into the jug they would put on the table. He held up one of the digger mugs and studied it closely. ‘The shape is bad, but light goes through the stuff they are made of, and I am thinking how nice it would be if I could make a cover for the windows from it so that we need not have the shutters closed in Winter. It would let in some light and we would not need to use so many candles. Imagine how pretty it would be with the sun shining through it.’

Zluty carried the jug of milk to the table, which was already set for his breakfast. He could tell from Bily’s chatter about the digger mugs that his brother did not want to talk about the queer sky, and so he merely held out his bowl for the hot porridge to be served and then poured on some of the warm creamy diggermilk and dribbled in a little honey and a sprinkling of nuts and dried berries. Bily served his own porridge and then there was no talk for a time.

Zluty was still eating the porridge when Bily left the table to wrap up the pancakes and pack them into the space Zluty had left for them.

‘You have not packed neatly enough, for there is less space than usual,’ he grumbled.

Zluty finished the last mouthful of porridge and hurried over to take the pancakes from his brother before Bily emptied the pack and discovered the extra jar he had put in to hold the berries. ‘You see, there is plenty of room for them, and they won’t be the least bit squashed,’ he insisted as he carefully put the pancakes inside one of the bigger pots. He fastened the top flap of the pack and tied his travelling scarf jauntily about his neck.

Bily helped him put on his pack, and then Zluty took up his new staff and went outside to get his water bottles. These were small and there were many of them. He must carry enough water to travel the full four days to the Northern Forest, and it was easier to carry it in small amounts hung evenly all about him. There were only two springs on the plain. One was beside the cottage and the other was inside a rift in the ground near the Northern Forest. Bily helped him attach the last of the bottles to hooks on the woven strap that ran across Zluty’s chest, and then the two brothers hugged one another warmly.

‘Travel safe and return soon,’ Bily said, trying to be brave and cheerful.

‘I will, I promise,’ Zluty replied, resisting the desire to reassure his brother about the odd sky, for that would only make him worry all the more. But he was glad to see Redwing glide down to sit in the bush nearest the door, where his brother lifted his hand in farewell. The black-and-red bird gave a trill of farewell and Zluty bowed to her to thank her for her good wishes – he supposed that was what she was saying – and then he set off, his heart lifting at the sight of the distant forest, despite the strangeness of the sky.