6

6

6

6

Bily had just finished carrying the last of the nests down into the cellar. It had taken him over an hour to persuade each bird that if the wind became any stronger it was likely to dislodge his or her nest. He had no doubt now that there was a storm coming, whether or not it was the redness in the sky or merely the thing pushing it. Aside from the growing force of the wind, his fur was fully fluffed. The birds knew it, too, yet without Redwing, Bily doubted he would have managed to convince them to let him shift their nests. Most of the parent birds had come down to the cellar with their nests, but there were a few who were too frightened. They were desperate to be reunited with their babies but they needed help to overcome their fear. Bily was crumbling some bread into a bowl to set in the cellar beneath the open trapdoor as an encouragement for them, when he heard a tearing noise from above.

He thought at once of the roof tiles.

Since midday the rising wind had been plucking and worrying at them. Though well made and carefully tied down, the woven tiles had yet to be repaired and strengthened for the Winter to come. If the wind managed to tear away one of the tiles, it was possible that, bit by bit, the rest would be torn away, and even if only a few patches in the roof were opened up, rain would get inside the cottage once the storm struck. It seldom rained on the plain, but Bily could smell it on the wind.

Opening the front door to go out and look at the roof, Bily was startled at how much stronger the wind had become. All of the bushes and plants were bent over under its force and some had even been completely stripped of their leaves. No wonder most of the birds had flown away. He backed away from the cottage to see the roof better.

It was dark because of the dull red sky, but he saw at once that the wind had torn away almost a whole line of tiles along the western side of the roof. Bily knew he ought to get the ladder and climb up onto the roof to tie the remaining tiles down, but the wind was so strong that he dared not try it. If only Zluty had been there to do it – he had no fear of heights.

Bily wrung his hands for a moment, wishing hopelessly for his brother, but he knew that Zluty could not help him now. This knowledge frightened him, but it steadied him, too, and let him see there was only one thing he could do.

Casting a final glance at the boiling red clouds drawing nearer every second, he ran back inside the house, wrenched open the cellar doors and began to roll up the rugs and push them down the steps. He took down the rug that hung over Zluty’s bed, and bundled up the bedding from both of their beds, pushing it all down into the cellar. Next, he carried down his weaving, the spindle and the bowl of breadcrumbs. Lighting a lantern he kept at the bottom of the steps, he was pleased to see that most of the birds were now sitting on the nests that he had tucked here and there.

He pushed the rugs and bedding to one side of the cellar, and went back up into the cottage to bring down his collection of feathers.

Puffing slightly as he made yet another trip down the steps, Bily prayed that all of his work would be for nothing, and that the roof tiles would hold. But even as he came up again from the cellar, he heard a long ominous ripping sound.

At the same moment he realised that he had forgotten to bring in any water. He did not want to face the tempest outside again, but there was nothing for it. He got two big urns and opened the door. The wind snatched it from his hands and threw it open with a loud bang before pushing at Bily as if it meant to knock him down.

Bily braced himself and shouldered his way outside, hauling out the urns after him and then dragging the door closed behind him. The garden heaved and churned in the heavy red light that suffused the late afternoon, making it seem to have come alive.

Bily dragged the urns around to the well and drew up buckets of water until he had filled them. Then he rolled them one at a time to the outside entrance to the cellar. Flinching from branches that lashed and flailed at him, he lowered first one urn and then the other into the cellar cave using a hook on a rope that ran up through another hook attached to outside of the cottage.

Propping the cellar door open so that the birds would not feel trapped, Bily ran back around the house to the door, noticing as he did so that two lines of the woven roof tiles had been torn off and the ones at the end of another line had begun to flap. There was nothing he could do, of course, but his heart ached as he went inside and saw the dark red sky was showing through the tiles in three separate places.

One of the shutters he had closed earlier rattled free of its hook, and the clatter it made as it banged open made his heart leap against his chest. He gathered his wits and ran to catch hold of it and push it closed. Even as he lifted the hook back into place, there was a great rushing roar outside that shook the cottage, and then came a cacophonous clattering and thudding on the roof and walls as if a hundred Zluty’s were outside hurling stones at the cottage.

Having no idea what was happening, Bily froze and waited for the terrible noise to stop. But it went on and on. He forced himself to go to the other side of the cottage where the tiles had been torn away so that he could look out. To his astonishment, he saw that great red stones were falling out of the sky. Even as he watched, several crashed through the hole to land on the rug below.

For a time he stood gaping at them in disbelief, then the large beams of wood overhead creaked ominously. Bily thought with horror of the red stones piling up on top of the roof, growing heavier and heavier, and backed away from the torn opening. He had been worried that things would get wet or be ruined, but now he saw there was a far greater danger.

Calling to Redwing, who was perched on the back of his chair by the fire, he ran to the cellar doors. Before he could descend the steps, he heard a violent crash from below. A moment later the birds that had taken refuge in the cellar exploded up into the cottage in a wild flurry of feathers and beaks, screeching, ‘Monster! Monster!’

‘Come back!’ cried Bily in alarm, as the birds looped and swooped in the air, knowing they would be killed if the roof of the cottage gave way under the stones. He was sure that their monster was only the door to the outside cellar entrance blowing shut in the wind. If only he had closed the outside trapdoor to the cellar after he had lowered the water urns!

‘There is no monster,’ Bily shouted, trying desperately to make himself heard over the screeching of the birds and the thunderous noise of the falling stones. ‘It is only the storm. We must go back down into the cellar where it is safe.’

None of the birds would listen and Bily saw that he would have to go down into the cellar to show them there was nothing to fear. When he was not devoured, the birds would realise they had made a mistake and return to their nests. On impulse, he took up the broom standing against the wall near the cellar opening before beginning to climb down the steps. The light given out by the lantern he had left on the bottom step was weak and fitful and Bily realised there must be very little oil left in its reservoir. He nearly groaned aloud but reminded himself that at least the jug of oil was in the cellar.

As he descended, the weight of earth between him and the cottage muffled the sound of the falling stones until Bily could only hear the soft swift thudding of his own heart. He realised that he was frightened and told himself sternly that there was no monster waiting to eat him in the cellar. Just the same, he was glad he had taken the broom.

By the time he got to the bottom step, Bily’s mouth was dry with fear. He knew that there was no such thing as a monster. But the thought came to him that if someone had told him the day before that stones would rain from the sky, he would have said that there was no such thing as a stone storm.

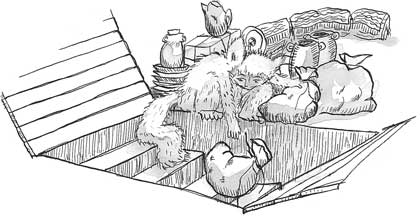

Bily peered around the cellar. He could just make out the humped shapes of bales of sweetgrass, sacks of grain and ground flour and the bedding he had thrown down earlier. Turning slowly, he ran his eyes along the rows of empty honey and tree sap jugs. Everything was exactly as it ought to be, except that when he looked down to the lower end of the sloping cellar, he saw that the trapdoor to the other entrance was completely smashed, splintered bits of it hanging down around the opening. Some stones had fallen through the gap, knocking over the ladder that usually rested against the wall under the trapdoor, but fortunately the water urns had not been broken.

Bily set down the broom and ran to roll the urns out of danger, thinking that the bush growing by the entrance must be partly shielding the opening for only a few stones had fallen into the cellar. None were big enough to have stove the door in and he wondered if the tree had been uprooted by the wind and had fallen on it.

One of the baby birds began to cheep piteously behind him, reminding Bily of the danger faced by the birds up in the cottage. He ran back up the steps and, to his relief, he found that most of the birds were now perched around the cellar doors peering down fearfully at him. Above them, Bily saw that there were now several places where the weight of the stones had torn holes in the roof. Worse, right above the cellar door, the roof tiles were sagging heavily.

‘Come into the cellar before the stones come through the roof!’ he begged the birds. ‘There is no monster and your eggs and nestlings grow cold.’

He looked at Redwing, who immediately launched herself through the opening. To his relief, the rest of the birds followed her. As soon as they had all come into the cellar, Bily reached up to close the doors over his head.

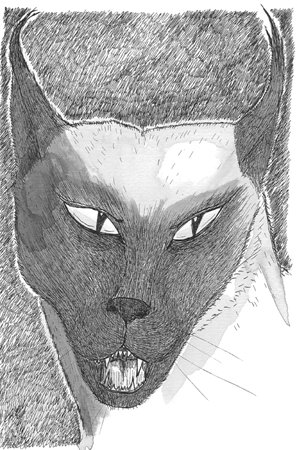

It was not a moment too soon, for he heard a loud ripping noise and a great clamour of stones falling. He went back down the steps again, careful not to stand on any of the birds. Clearly, they were not going to go any further into the cellar without him, even though Redwing had flown down to where the lantern stood. Its flame was almost out when he reached the bottom of the steps and Bily carried it over to the shelf by the bales of sweetgrass, where he kept the lantern oil. But even as he set it down he froze, for there, in the corner of the cellar, was a pair of huge glowing yellow eyes.