16

16

16

16

Zluty woke just before dawn feeling very stiff. He opened his eyes and saw Bily lying sound asleep, his cheeks pink from the ruddy glow of the embers of the dying fire. Despite all that he had endured in the last few days, Bily’s face was serene in sleep and Zluty felt a rush of love for his brother. He must have spent hours grooming himself the night before, because his fur was as white and soft as ever.

Zluty got out of his bed and padded away from the fire to give himself a good brush. Then he gathered some more ground cones and crept back to build up the fire, trying to be quiet so that he would not wake Bily. The bees were awake and the three males flew out of their jar to accompany him when he walked down to the pool of water beside the cottage. It was a murky colour but it smelled clean enough for him to wash his face in. It was definitely deeper than it had been and he thought of what Bily had told him about the crack in the floor of the cellar cave, and the water rushing in even after the rain had stopped. The combination of the stone storm and the heavy rain must have changed the ground so that what had been a trickle of water from deep underground had increased to a strong gush with more than one outlet.

If he was right, there could be no hope of rebuilding the old cottage. They would have to build a new one on higher ground. For now, the best they could do for a shelter was to use the stones from the broken wall to make a small hut. The bits of the old egg house in the cellar would have to serve as a roof. It would have to be a very small hut though, because they would need to spend every moment gathering supplies for the coming Winter.

Zluty decided that since he was awake he might as well start bringing up anything that could be salvaged from the cellar. He did not like the idea of getting wet again, especially when he had just combed himself, but it would have to be done sooner or later and at least there was now a fire waiting to warm him.

He climbed over the broken wall and found himself right alongside the pallet where the monster slept. It was panting slightly and Zluty wondered if it was thirsty. He took up the bowl on the ground, only to find there was water in it.

Suddenly the monster woke and reared up to snarl terrifyingly at him, showing all of its sharp teeth.

Zluty’s fur fluffed with fright, but already the monster was sinking back.

‘So it was not a dream,’ it rasped.

Zluty swallowed hard, thinking how much bigger it appeared in the daylight. He told himself that it only looked that way because its long thick fur had dried and fluffed out. But it was not only its size that daunted him. The monster had long sharp claws and pointed white teeth. Even its ears were sharply pointed. Everything about it looked dangerous. The previous night when they had brought it out of the cellar, it had looked so ill and feverish that Zluty had felt sure it would not wake again. But the eyes fixed upon him now were bright with life and intelligence, and he was within easy reach of its paws if it had recovered enough to use them.

‘I am sorry if I frightened you,’ said the monster gravely.

Zluty swallowed and said as firmly as he could, ‘Are you hungry? I can get you some food.’

The monster said, ‘I am thirsty.’

Zluty was steeling himself to step nearer to the pallet when Bily touched him on the shoulder. Zluty got such a fright he dropped the bowl, which crashed to the ground and shattered.

‘Oh no!’ he groaned, for it was a bowl that his brother had spent hours colouring delicately with strokes of a feather.

‘Never mind,’ Bily said. ‘So much has been smashed that one more thing hardly matters.’

Zluty stared at his brother in disbelief, for Bily had always set great store on the things he made. He had sometimes even wept when something he particularly liked broke in the firing kiln.

Zluty said, ‘The … the monster was thirsty.’

‘That is a good sign,’ Bily approved. ‘Its fever broke last night.’ He bent down and carefully picked up a broken piece of the bowl that still held water. Zluty watched as he brought it to the monster, marvelling at Bily’s fearlessness as it drank. When it lifted its head, licking drops of water from its muzzle with its long red tongue, Zluty swallowed hard.

‘You needn’t be afraid,’ Bily said, to Zluty’s mortification, setting the broken bowl down carefully. ‘If it was going to eat me it could easily have done it by now.’

‘Right now I am so weak that your bird friend could land on my nose and pull my whiskers out and I could not lift a paw to stop her,’ said the monster.

Zluty blushed but was secretly rather relieved to hear this. He said nothing as he watched Bily examine the blackclaw bite. The monster only winced.

‘It looks much better,’ Bily murmured.

‘It is still very sore,’ said the monster through gritted teeth.

Bily ignored this and went back to the fire to get some warm water to bathe the paw again. Zluty remained with the monster, but neither spoke. When Bily returned, he had brought a bowl of cold mushrooms as well as the water. He set the food down where the monster could reach it and began to wash the paw, saying, ‘It had better be left uncovered from now on. The air will dry it and the sun will be good for it, but you must move it as little as possible.’

‘You sound exactly like a seer,’ grumbled the monster.

‘What is a seer?’ Zluty asked curiously.

‘One among my people who sees things others do not,’ said the monster. ‘So it is said.’

‘What do you mean by “your people”?’ Zluty asked curiously.

‘I mean those like me. My kind. My brothers and sisters and my mother and father and my cousins and uncles but also those that are not of my blood,’ answered the monster.

‘I do not know what any of those other things are, other than brother,’ said Zluty.

‘You have no family?’ asked the monster. ‘There have been times when I have wished it so for myself. But tell me, why do you and your brother choose to live apart from your kind?’

‘There are no others of our kind,’ Zluty said.

The monster stared at him. ‘Something cannot come from nothing. You must have had a mother and father.’

‘We came from an egg,’ Zluty said.

‘You both came from the same egg?’

‘Of course,’ said Bily, who had finished with the paw. ‘Sometimes two birds are born from the same egg.’

‘But you are not birds,’ said the monster.

‘Of course not,’ Bily said. ‘But birds are not the only things born out of eggs. The dusk lizard comes out of an egg, too.’

‘A bird or a lizard lays the egg from which a bird or a lizard is born,’ said the monster. ‘Where is the She that laid your egg?’

Bily and Zluty looked at one another, for it was not a thing they had ever thought about before. Bily said slowly, ‘I suppose the egg was laid and then whatever laid it left, just as the dusk lizard lays her eggs in the earth and covers them over before leaving.’

The monster opened its mouth, but before it could speak a fit of coughing overtook it.

Bily tut-tutted and drew its blankets over it. ‘You must eat and then rest.’

The monster lay down its great head, and when its eyes closed Bily and Zluty exchanged a look. For the first time, Zluty felt some of the pity that his brother felt for the monster, for clearly it was still very weak.

Several peaceful though oddly makeshift days followed during which the water in the black pool and the cellar did not recede, though neither did it deepen. Zluty wondered if he was wrong about the spring. Maybe the cracks in the ground were closing up and the waters would recede after some time. Then they could rebuild their old cottage in the Spring.

Bily and Zluty began to raise the beginnings of a second wall, for Zluty had pointed out that even if the cellar did eventually drain, it would not do so in time to be used as a shelter for the Winter.

Little by little they brought out all that could be salvaged from the cellar, but to Billy’s disappointment, they had not yet managed to find his precious spindle. Fortunately, they had been able to get the water jugs out because the water in the pool was beginning to grow stagnant.

This puzzled Zluty, for surely spring water was flowing into it through the submerged well, and ought to be refreshing it. The only answer seemed to be that there was something in the stones that had fallen into the well that was fouling it. In time, he was sure the spring would recover, but until then the water in the jugs was all they had besides the pool in the cave by the Northern Forest. Of course, the diggers would always trade diggermilk for food. But food was soon likely to be another problem.

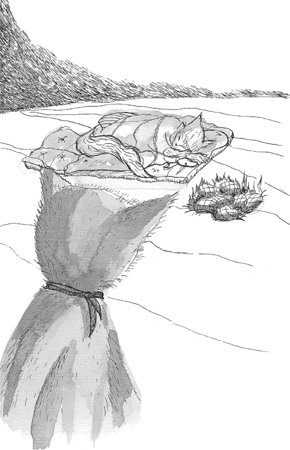

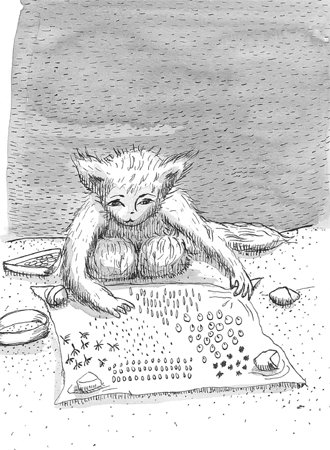

One day, Zluty left Bily laying out his seeds to dry in the hope that some might be salvaged, and walked a half day East to look at the patch of sweetgrass he usually harvested for new bedding. The crop had been so completely destroyed by the stonefall that it might never have existed.

The next day he went further East to dig for orange tubers, having warned Bily that he would not return until the following day. He managed to locate a few roots, but they smelled strongly of the red stones, and Redwing and the other birds had refused utterly to eat anything that smelled of them, explaining that it would make them sick.

Two days later, Zluty went South to the swamp. He had been afraid that the wild rice would also be tainted by the red stones, but the swamp had swollen to many times its size, drowning not only the openings to the blackclaw nests but all the wild rice.

Zluty was very glad when he came across a tuft of bright yellow flowers of a kind he had never seen before on the way back. Wild flowers often grew on ledges in the rifts after rain, and although their smell told Zluty the flowers were inedible, he knew Bily would enjoy their colour and perhaps the bees would be able to harvest the pollen. It was much better not to go back empty-handed, given his bad news.

Bily had exclaimed in pleasure at the sight of the flowers, and the bees emerged from their jar to swoop on them at once. But when Zluty told him about the swamp, Bily’s face fell. He knew as well as Zluty that even with all that his brother had brought back from his trip to the Northern Forest, there was too little they had managed to salvage from the cellar storage to last them the whole Winter without the wild crops.

Bily might have worried more if the monster’s cough had not that afternoon turned into a severe chill. The monster shivered and shook the whole evening, and though Bily tended to it constantly, replacing the blankets that kept falling off, and feeding it warmed honey water that Zluty brought down from the fire, it was worse by nightfall. The monster was so painfully thin now that its bones showed through its skin, and looking at it, Zluty could not help but wondering if it would not have been better for it to die swiftly like the diggers, rather than to linger on in this dreadful way.

But he said nothing of that to Bily whose heart was set on saving the monster.

Nor did he say that, even if the monster did survive, they were all likely to die of thirst or hunger before the Winter was out. He had a habit of protecting his gentle brother, but after he helped Bily drag his mattress down to flat ground so that they could pull the pallet out of the ruins and he could sleep by the monster, Zluty sat on the broken stone wall reflecting that, for the first time in his life, he did not know what to do next.