OUTRO

The Pirate’s Dilemma

Changing the Game Theory

The game has changed.

Youth movements that might have seemed like fads planted some radical ideas into the heads of those who grew up under their influence, and nothing has been quite the same since.

Punk made it very clear that we could do everything ourselves, and purpose should be at least as important as profit. Pirates, like offshore radio DJs, create periods of chaos and anarchy, but improve things for the rest of us by doing so. The millions of us who remix video games, music, films, and fashion designs are expanding and improving on those industries, forcing those who make the laws to reexamine how we treat intellectual property. The new breed of street artists seeking to enhance our surroundings as opposed to vandalizing them act in the public interest, if only unintentionally, by counteracting the advertising cluttering public spaces. Thanks to the influence of 1960s and ’70s counterculture, and the rave revolutionaries of the ’80s and ’90s, the dream of creating an all-powerful social machine has been realized in the personal computer. Open-source technology has proved to be just as effective as—and in many cases more effective than—free-market competition or government regulation when it comes to generating money, efficiency, creativity, and social progress. Hip-hop was born out of a desire to improve society for a marginalized few, but because of its ability to communicate so effectively, now has the potential to improve it for the marginalized many. And just as mass culture thought it had figured out how to control and use youth cultures, they evolved again. Mass culture needs to learn from the ways youth cultures behave and think, not just use them for their good looks.

Because all these ideas are coming together in the wider world at the same time, a new period of chaos has ensued as the Information Age has grown into a petulant teenager itself. Now we are all capable of acting like pirates, or being devoured by them. Now we all have to consider what the new conditions of this difficult adolescence mean, and how we should approach them. Now that the game has changed so much, we need to reexamine the theory behind the game.

The answer to the Pirate’s Dilemma lies in something economists call game theory. Game theory examines situations where multiple players in a game make decisions based on what the other players will do, like an academic version of poker. It is used to model social situations in which decision makers interact with other agents, and often assumes individuals will act only in their own self-interest.

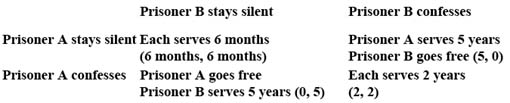

A game called the Prisoner’s Dilemma is a simple, well-known game used to illustrate this point. Developed in the 1950s by the RAND corporation (a global policy think tank which advises the U.S. armed forces, among other things), the game goes like this: two suspects, Prisoner A and Prisoner B, are caught with stolen goods and arrested under suspicion of burglary. But the police don’t have enough evidence to convict either prisoner unless one, or both of them, confesses. The police separate the two prisoners so they cannot communicate, and offer them both the same deal: if both of them confess, each will receive a two-year sentence. If neither of them confesses, the cops can’t prove they were the burglars, and each prisoner will instead be sentenced to only six months in jail for possession of stolen goods. But if Prisoner A confesses and Prisoner B keeps his mouth shut, Prisoner A will walk free and Prisoner B will receive the full five-year sentence for the crime, on the strength of Prisoner A’s testimony. The same holds true if Prisoner B confesses and Prisoner A does not. Neither Prisoner A nor Prisoner B knows for sure what choice the other will make. Each has two options, and there are four possible outcomes.

Each prisoner can either stay silent and hope the other prisoner does the same, or betray the other in return for a lighter sentence. The outcome of each choice depends on the choice of the other prisoner, but each prisoner must choose without knowing what his accomplice will do.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Assuming each will act in his own self-interest, the only logical outcome is that both prisoners will always confess. Even if Prisoner A thinks Prisoner B will not talk, his best move is still to rat him out and try to go free rather than risk the five-year sentence. If Prisoner A suspects Prisoner B will talk, his best move is to snitch as well and receive two years instead of five. Prisoner B will always reason the same way about Prisoner A, too, so betraying the other prisoner and confessing is always the dominant strategy. Both prisoners would get lower sentences if they cooperated with each other and remained silent, but assuming the other will most likely snitch out of self-interest, their best choice is always to do the same. Playing the game using self-interest will always result in each prisoner being worse off than if they had cooperated with each other. Yet when faced with this dilemma, each prisoner will choose to betray the other every time, because of their uncertainty about what the other prisoner might do.

As a society we often subscribe—in theory, at least—to the idea that we will exclusively act in our own self-interest. This theory has been a dominant force in economics, political science, military strategy, psychology, and many other disciplines since the 1950s. It has informed some of the most important decisions the human race has ever made, from the nuclear arms race of the Cold War to the way we share all kinds of resources today. This simple game of two paranoid prisoners trying to cut a shady deal helped shape the structure behind the supposedly dog-eat-dog world we live in.

Game theory is an incredibly useful tool, and more advanced versions of the game allow for cooperation between players, but according to the most basic Prisoner’s Dilemma game outlined here, the idea of people acting in the interests of one another is naive. But in practice, it is obvious the game is flawed. The most basic assumption—that we all act only in our own self-interest—is simply not true. When economists test this theory, real people do not always act this way. In real life, in every corner of society, people cooperate with one another in the interest of both the public good and their own private interest. That’s why we have nonprofits, nurses, and teachers. As Muhammad Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank and winner of the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize put it, “A human being can do many other things, but economics doesn’t leave any room for expressing them.”

When the market won’t express something, pirates will. Pirates acting in their own self-interest and in the interests of their communities are today some of the most ruthless innovators on the planet.

Solving the Pirate’s Dilemma

From struggling musicians to movie executives, people in many industries already feel that their future is under fire from piracy. But there are answers. Solving the Pirate’s Dilemma can also be expressed as a simple game illustrating how people, businesses, and markets facing a threat from piracy should respond. It shows us how to compete when copyright protections are no longer keeping pirates at bay, or when we are faced with the dilemma of whether to share products with competitors and consumers.

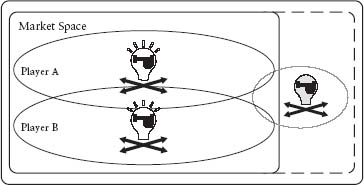

In the Pirate’s Dilemma, Players A and B are not burglars but individuals or companies selling competing products. The players are not being threatened by police, but by pirates: those creating a new space outside of the traditional, legitimate market.

Pirates create a gap outside of the market.

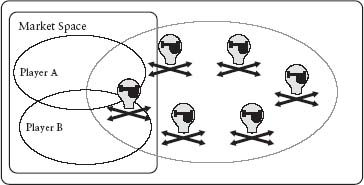

Let’s assume our definition of “pirates” also includes those providing free substitute products powered by altruism, such as open-source software, for example. These pirates can add value to society, but in doing so take value from companies or individuals such as Players A and B. When people switch to Linux, for example, that takes market share away from Microsoft.

As we saw in chapter 2, when pirates create value for society, society supports them. If the pirates grow and take a larger chunk out of the traditional market space, Players A and B soon find they face a Pirate’s Dilemma. Do they try to fight piracy with the law, at the risk of alienating the public, the way the record business did, or do they do what iTunes did, and compete with the pirates in the new market space?

If piracy grows, Players A and B will face a Pirate’s Dilemma.

If both decide to fight piracy, and if that piracy is providing no real value to society, then Players A and B may be able to quash the threat the pirates pose, and the marketplace will return to the way it was in Figure 1. If we imagine Players A and B were in the luxury handbag business, they would be unwise to compete with pirates selling $25 knockoffs of their $2,000 handbags. If you’re a consumer in the market for a $2,000 handbag, a $25 imitation is probably of no value to you, and there is no value to be gained by the luxury handbag producer by lowering their prices—in this instance it would hurt their brand to compete. The strong arm of the law will, in many cases, be the best option.

But if Players A and B, or the market space they inhabit, is inefficient—if there is a better way for society to gain the value that Players A and B provide—there will always be a threat from pirates. If a large amount of consumers will always prefer a $5 pirate copy of a movie in its opening week to a $12 box office ticket and overpriced popcorn, demand for pirated movies will persist. If a developing nation can’t afford name-brand, life-saving drugs, those brands will always have to deal with pill pirates in those markets. Prohibition is unlikely to work in these cases, and inefficient industries will continue to have a problem until they react in the marketplace instead of the courts.

The decision each player makes about how to respond also poses a threat to the other player, as it does in a Prisoner’s Dilemma. If pirates begin to have a serious effect on their market share, both Players A and B will (or at least, should) be tempted to compete with them. If either decides to compete with pirates by moving into the new market space, they can also cut into the market share of their competitor.

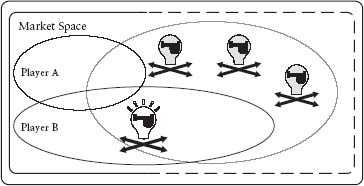

Imagine Players A and B are drug companies, and the pirates are those producing generic pills in a developing country. By fighting the pill pirates in this case, neither player stands to make a great deal of money, because the new market doesn’t have much. But not allowing people access to life-saving drugs means people will die needlessly, piracy will be inevitable, and the company’s image will be tarnished. But if Player B starts producing drugs in this market and competing with the pill pirates, they will gain market share (which could become profitable in time), save lives, and improve their reputation as a brand. In a world where advertising isn’t working quite so well anymore, creating value for society like this is a great way to make an authentic connection to consumers. Player B’s actions will also undermine Player A’s position in the market. If Player B competes and Player A doesn’t, B will cut into A’s market share, and the share taken by the pirates.

If Player B competes, society gains, but the pirates and Player A lose out.

Once a player decides to compete, the new market space the pirates inhabit becomes legitimized. This adds value to society, creating a greater market space in which players can pursue profits. In this instance, Player A will also be forced to compete the same way in the long term, or risk going out of business altogether.

The new market space becomes legitimized, and Player A must compete.

Imagine Player B is an open-source software company, such as Linux, operating in a market where there is widespread piracy, such as China. Linux gains market share by competing with the pirates—giving away its products for free and selling customized products and support to make a profit. Linux becomes more efficient (by sharing this product with outside contributors who improve it), creates value for society (as much as 12 billion Euros worth, according to the E.U. study mentioned in chapter 5), and takes market share away from Player A as well the pirates.

Now imagine Player A is Microsoft—its market share in China is under fire from both pirates and free substitutes like Linux. What is Microsoft supposed to do? In this situation, competing seems to be the only choice, other than being forced out of the market altogether. Microsoft’s official position on piracy has traditionally been one of zero tolerance, but Bill Gates acknowledged this reality to a group of students in 1998. “Although about 3 million computers get sold every year in China, people don’t pay for the software,” said Gates to an audience at the University of Washington. “Someday they will, though, and as long as they’re going to steal it, we want them to steal ours. They’ll get sort of addicted, and then we’ll somehow figure out how to collect sometime in the next decade.”

In this model, whenever pirates are adding value to society, society will always demand that the players compete with them in the long term. In this case, the player who competes first will stand a better chance of gaining the advantage. In the simple version of the Prisoner's Dilemma, only self-interest rules. But in a Pirate’s Dilemma, what’s best for society as a whole is also an important factor. Because players and pirates alike can be motivated by both self-interest and what’s best for society, the game has changed.

The Pirate’s Dilemma

What is emerging from the ideas youth culture pushed on the world is a more democratic strain of capitalism. People, firms, and governments are being forced to do the right thing by a new breed of rebels using a cutthroat style of competition, which combines both their self-interest and the good of the community to beat traditional business models. We are starting to see a very different picture of how the world might work. A world of competitive pirates, it seems, is a better place to be than one full of paranoid prisoners.

Free at Last

Pirates are taking over the good ship capitalism, but they’re not here to sink it. Instead they will plug the holes, keep it afloat, and propel it forward. The mass market will still be here for a long while. This book you are holding—static words printed on thin slices of dead tree brought to you by a large media company—is living proof of that. The book industry has been fortunate: books are some of the easiest things to pirate, yet the majority of book readers still choose the treeware versions rather than downloading software-based substitutes. Not everything can be replaced by an electronically transmitted copy, for now, at least.

As we learn to pirate more of the things we buy and sell, many industries will face short-term uncertainties. But looking at the history of youth movements, the social experiments that took hold by figuring out new ways to share, remix, and produce culture, in the long term, the benefits of this new, more democratic system seem clear. It is down to every one of us to approach the Pirate’s Dilemma from our own unique perspective and to apply the best option to our particular situation.

Over the past few decades in the West, we have entered a period of hyperindividualism, which has its pros and cons. But the power of billions of connected individuals, now flexing more power than markets, governments, and corporations using new ideas our economic model cannot yet comprehend, should be welcomed. Punk capitalists mix altruism with self-interest to compete on new levels the free market by itself cannot reach.

The early years of the twenty-first century have conjured a new worldview, one imagined by radicals and subversives who used youth cultures to prove there were better ways of doing things. In the future, loose-knit networks and open-source communities may sit side by side as equal powers with both governments and the free market. Punk Capitalism isn’t about big government or big markets but about a new breed of incredibly efficient networks. This is not digital communism, this isn’t central planning. It is in fact quite the opposite: a new kind of decentralized democracy made possible by changes in technology. Piracy isn’t just another business model, it’s one of the greatest business models we have.

Acting like a pirate—taking value from the market, or creating new spaces outside of the market and giving it back to the community, whether it’s with free open-source software or selling cheap Starbury sneakers—is a great way to serve public interests and a great way to make an authentic connection to a new audience.

Many industries and markets have not yet felt the effects of pirates and the forces of change we have discussed here. But with new technologies such as self-replicating 3-D printers lurking on the horizon, nobody is safe. The Pirate’s Dilemma needs to be taken seriously by all of us, because tomorrow pirates could be coming to an industry near you.