CHAPTER 6

Real Talk

How Hip-Hop Makes Billions and Could Bring About World Peace

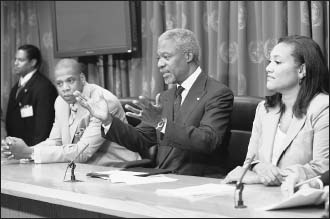

Secretary-General Kofi Annan (center), flanked by Christina Norman (right), president of MTV, and Shawn “Jay-Z” Carter (left), president and CEO of Def Jam Records, addressing a press conference to launch the United Nations–MTV global campaign on water, at U.N. Headquarters in New York.

August 2006 © U.N. Photo/Paulo Filgueiras

One-man corporate behemoth Sean Combs/Puff Daddy/Diddy/Whatever-his-name-will-be-by-the-time-you-read-this flounces in to Burger King with his camera crew in tow. Bedecked in oversized Jackie-O stunna shades, a black and gold Biggie T-shirt, and a leather jacket, he’s shooting a promotion with the multinational fast-food chain that is almost as famous as he is, to air online on TV site YouTube. “If y’all don’t know, I’m here to announce to y’all that Burger King has named me the king of music and fashion,” he crows in the grainy video clip.

The sight of a Burger King uniform alone should be enough evidence that this company isn’t really in a position to be dishing out such sartorial endorsements. But the real problem here is where Burger King and Diddy were at. The comfort zone for this type of collaboration is the one-way, mainstream media where the broadcaster controls the message and celebrities can get away with the cheesiest of cheesy promotions. But this isn’t how you roll on interactive two-way streets such as YouTube. Here, hip-hop legend or not, if the crowd catches you slipping, you better be ready for some real beef.

The video shows Diddy making for the counter and ordering a Whopper before turning to the camera to explain how Burger King had bought a channel just for him and his celebrity friends. A few seconds after ordering, he starts throwing a hissy fit at the poor kid behind the register for fixing his burger too slowly, then muttering begrudgingly when actually asked to pay for it.

The spot was a bad look for Diddy, normally a master at manipulating the media. It drew widespread disdain from the blogosphere, a 2 out of 5 rating on YouTube, and more than seventeen hundred mostly negative viewer comments within a few hours. It served as a depressing reminder of the stagnant state of mainstream hip-hop and how far removed it had become from the ideals that birthed it. On YouTube this kind of posturing was, as MTV News later put it, “about as welcome as a Whopper at a PETA convention.”

Diddy failed to keep it real. He didn’t show any respect to his audience, delivering a viral video devoid of value, stumbling on to YouTube waving money around, showing no understanding of the medium (you don’t need to wave any money around on YouTube—you can post up as many videos as you like and create your own channels free of charge). This was why it wasn’t long before the self-proclaimed king of music and fashion was taken down by one of YouTube’s democratically elected court jesters: amateur filmmaker Lisa Nova.

Lisa stepped up to battle Diddy with her own viral counterpunch, a video of herself walking to her local fruit stand, with no makeup on, hair scraped back, ensconced in an old hoodie. Matching Diddy’s swagger with an equal measure of sarcasm, she said, “I’m here to announce that me and the fruit stand have gotten together, and the fruit stand has decided to name me the queen of music and fashion.” Ordering her fruit with everything on it (salt, pepper, mayonnaise, chili…), Lisa explains, “Me and the fruit stand have gotten together to buy our own channel on YouTube, even though they’re free…just ’cos we’re that smart,” before giving the fruit vendor grief for not getting her stuff fast enough, muttering when asked to pay for it, etc.

It was an instant hit, scoring 5 out of 5, much online worship, and sparking even more Diddy TV parodies. Nova was crowned queen of YouTube for the next five minutes (which is the maximum amount of time you can be the king/queen of YouTube before the next online viral video sensation comes along), while Diddy’s people quietly removed his original clip. Nova has no hip-hop credentials whatsoever, but she still managed to bring it to one of the movement’s most famous icons because she kept it real.

The importance of authenticity is one of the most misunderstood factors in hip-hop—even Diddy gets it wrong sometimes. Hip-hop has dominated youth culture for decades, and has bred brilliant entrepreneurs who are now among the richest people in America. It is also increasingly informing thinkers, politicians, and decision makers as the hip-hop generation come of age.

Keeping it real and striking a chord with a huge audience is how hip-hop took over, but keeping it real is a trend bigger than hip-hop, now used to speak to consumers, voters, and entire nations. As we saw in chapter 4, we are becoming more immune to marketing—consumers are as brand-savvy as ad agencies, and we only respond to advertising with a genuine value for us. It doesn’t matter if you are a student sending out a résumé, a CEO repositioning a brand, or a rapper promoting a mixtape. Your audience is real, and as Jay-Z once put it, “real recognize real,” so you have to be, too, or they won’t listen.

Technology has connected us in new ways—we have the opportunity to speak to more people than at any time previously in history. Now we need a way to communicate effectively. In youth culture, the dominant language is hip-hop. In the grand scheme of things, the root of this language is real talk—the art of making authentic connections.

Reality Used to Be a Friend of Mine

Today consumers crave reality. Previous generations grew up on TV shows such as I Love Lucy, wanting to believe in an ideal dream world. Now magazines snap celebrities warts, nip slips, and all, and “reality” TV thrives on half-truths stranger than fiction. We take comfort in how weird everybody else is.

In the past thirty-years, the hip-hop generation* has discarded the concept of cultural authority. In a world where product placements are broadcast by trusted networks as news pieces and we are approached by make-believe MySpace friends made of spam, it’s getting harder to believe what we see and hear.

As a result, we thirst for authenticity like never before. With mass personalization has come the need for everything to feel more personal. The only way to move the crowd and rally a community is with genuine connections. But the need to forge a real bond with a mistrusting audience is not new.

As Saul Alinsky, the godfather of activism and rallying communities, wrote in Rules for Radicals, “In the beginning the incoming organizer must establish his identity or, putting it another way, get his license to operate. He must have a reason for being there, a reason acceptable to the people.” The way hip-hop initially took shape as a grassroots movement and evolved into a global language of authenticity could have come right out of the radical activists’ textbook.

In the beginning, hip-hop got its license to operate in the South Bronx because it was an escape, a way for people to stop fighting and to channel that energy into breaking, rapping, DJing, and graffiti. It got acceptance outside of the Bronx by borrowing and remixing elements from other scenes, such as punk, funk, and disco, and whole new audiences found themselves identifying with it. Anyone can be part of hip-hop, anyone can borrow it, but nobody can own it. It is defined by participation and collaboration.

Hip-hop is not a sound, culture, or movement at all. It is an open-source system, which is why it has become such a great business model. Sociological shifts usually rob youth cultures of their value. Teddy boys, new romantics, and greasers no longer seem relevant or threatening to most people, but hip-hop is still right there because it evolves constantly. Many youth cultures stop evolving at some point, develop too many rigid structures and pretensions, stagnate, and die. Others are devoured by the mainstream until nothing is left. But hip-hop refuses to go out like that, instead using the remix to devour everything in its path.

Globalization has only worked to hip-hop’s advantage. But it is not a colonial powerhouse with lesser regional outposts; it is a decentralized network that has self-sufficient hubs on every continent. It is a model of how globalization should work. Around the world it has been appropriated into many localized versions, which together form a loose-knit, open-source network through which people can communicate, collaborate, and empower themselves.

The world music on sale in the front of Starbucks won’t unite the planet in this way, but hip-hop is truly universal. It uses cultural differences as instruments to celebrate our similarities, as part of a global drum pattern beating out a desire for change. Hip-hop doesn’t recognize or respect tradition in the traditional sense. It grew from a community who’d had their history stolen, and while many cultures have long been defined and confined by their histories, hip-hop took over because it didn’t have to stick to just one, and as a result it is now capable of speaking to us all.

Hip-hop had a license to operate in the Bronx, but by relying on authentic connections, it now has a license to operate everywhere. Burger King and Diddy didn’t make this kind of connection, but the story of one of the first hip-hop entrepreneurs to turn the scene into a brand, outside the world of music, is a story of authentic connection that begins in another chain restaurant.

Escape from the Red Lobster

Many good stories are told in three acts. But Daymond John’s is a story better told with three hats. Hat one, scene one, opens in Hollis, Queens, in the early 1990s, where John is working at the Red Lobster restaurant. Under the waiter’s hat is a frustrated entrepreneur obsessed with hip-hop culture. “It was always huge to me,” he reminisces. “When I was eleven, twelve years old and it was just the mixtapes, it was huge, it was as big as the world is.”

Maybe there was something in the water in Hollis, because more than a few visionaries who grew up there could clearly see there was something in hip-hop. In his immediate circle of friends was Irv Gotti, who would go on to found the multimillion-dollar record label Murder, Inc., and Hype Williams, who would become rap music’s most legendary video director. Russell Simmons, founder of Def Jam Records and one of America’s most prolific entrepreneurs, also hails from there.

Daymond John started in hip-hop as a break-dancer, calling himself “Kid Express.” He caught a lucky break in the 1980s when yet another prolific teen from Queens, named James Todd Smith III, better known as LL Cool J, went on tour. John got the chance to tag along, and was fast-tracked into the scene’s inner circle. “At that tour I met everybody else and ended up going to a lot of tours,” he remembers. Here his role in the hip-hop world began to take shape.

Enamored with hip-hop fashion, John became something of a style scientist, rocking classic hip-hop brands such as Ellesse, Le Coq Sportif, and Fila, and pulling old skool power moves such as lacing his kicks chessboard style, pin-tucking his pants into his socks, and perfect-creasing his Levi’s. Daymond John’s fashion game was mighty healthy, and it led him to a revelation. “Kids would wanna buy the clothes off my back! I realized that this was a culture and that people were dying to get ahold of it. This was a movement that could rival the civil rights time, the Harlem Renaissance, it was a movement where everybody was on the same page, it was more than just the songs.”

But John’s idealistic vision became clouded when some of the brands he worshiped seemingly betrayed him. “Right around 1990, 1991, I heard that an executive over at Timberland had made a comment, something like ‘we don’t sell our boots to drug dealers,’” he recalls. “What that is basically saying is that the African Americans that were buying his boots were drug dealers. If you add that to the other rumors that I heard about Tommy Hilfiger saying he doesn’t make clothes for us, and Calvin Klein…whether they were true or not, now being in the business I know that 90 percent of the rumors you hear are bullshit. But at that point, it was all coming back to the community. I was frustrated because I knew how religiously I bought a lot of those products.”

The tours ended, and Kid Express’s fast track slowed to a halt. By the time he found himself sidelined at the Red Lobster, John’s enthusiasm for hip-hop was clashing with his resentment of the brands he had idolized and their seemingly negative attitude toward the culture.

John came across the second hat to shape his destiny while out shopping in Manhattan one afternoon. Shocked at the $20 price tag of a knitted cap, he thought, For $20, I could make twenty of these a day. And suddenly it all clicked. His entrepreneurial spirit, belief in the power of hip-hop, and passion for fashion came together, and so begins the story of Team FUBU.

John recruited three friends and formed For Us, By Us—FUBU for short—a name that stood for the team’s genuine commitment to the hip-hop community. They began stitching together their own D.I.Y. hats, and after making $800 in one day selling them outside a mall in Queens, they realized they were on to something. Soon they were turning out T-shirts, baseball caps, and polo shirts, too. The money began to roll in. John quit Red Lobster in 1992, and Team FUBU turned pro.

John set up FUBU’s headquarters and factory floor in the basement of his house, which he remortgaged to finance the business. Through friends such as Hype Williams, he persuaded many major artists such as ODB, Mariah Carey, Busta Rhymes, and Run-D.M.C. to wear FUBU clothing in their videos. “They wore them for different reasons,” Daymond explains. “They wore them to support us, and secondly we were genuinely fans when we came there, we were honored just to be in their presence. When the artists’ stylists would go to Gucci and them guys, they would say, ‘Get the fuck outta here, we don’t like rappers.’ And if a company did come down, they would barely even know the rappers’ names and have no respect, it was like, ‘Here, wear this, you’re lucky we’re even here.’ And at this point these rappers are millionaires. They don’t need the stuff like that, y’know? So it was a movement that was happening that nobody else realized. It was us starting to empower ourselves.”

The story of hip-hop is one of a new generation empowering itself by taking down the mainstream from the inside, and the next turn Team FUBU would take was classic hip-hop. By the midnineties FUBU was doing well but found itself stuck under a glass ceiling, unable to get distribution in many mainstream stores. This ceiling was cracked by hat number three, worn by John’s old friend and unofficial ambassador for FUBU: LL Cool J.

FUBU was one of the first clothing lines to spring from the font of hip-hop culture, but by the midnineties many brands had caught on to the movement’s power as a marketing tool. So it was no surprise when in 1997 the Gap hired LL Cool J to do a TV spot, kitted out in Gap clothing. When LL told John the news, the FUBU CEO made an audacious request.

“LL didn’t want to do it at all at first,” he told me. “I understand why, he had several endorsement deals on the table. But believe it or not, in the end LL said to me, ‘You know what? I’m gonna do this, and it’s really not something that’s good for my career.’”

On the day of the shoot, LL walked onto the set wearing Gap jeans and a Gap shirt, as per the advertising agency brief. But he was also sporting a powder-blue baseball cap. As John tells it, LL said to Gap’s people ‘I got this little company that I have, can I wear the hat inside the commercial?’ And the Gap says ‘No problem.’ In their mind it’s like, ‘Who gives a fuck?’”

With cameras rolling and music booming, LL launched into his thirty-second freestyle as required, dropping watertight rhymes. None of the ad execs saw anything out of the ordinary when he turned and looked directly into the camera, the FUBU logo on his hat clearly visible, finishing his verse with this line:

For Us, By Us, on the down low.

The ad shattered FUBU’s glass ceiling, not to mention a few ad execs’ careers. “What he was saying to every hip kid in America was this is a FUBU commercial, and I’m slipping it in here and they don’t even know,” says John. “It was like the Freemasons’ sign. It took Gap about a month to find out. When they did, they pulled the commercial, fired the agency and a lot of people at the Gap because of it. A year later, they come to find out that sales at Gap to African Americans had gone up by some astronomical number, because people were going to the Gap because that’s where they thought our goods were! They reran the commercials after that, and it aired for a long period of time.”

Team FUBU is now a multimillion-dollar brand playing in the big leagues. It grossed an estimated $370 million in 2006, and it operates in more than five thousand stores in some twenty-six countries. The glass ceiling is a distant memory, but FUBU has continued to grow by operating on the down low—stenciling FUBU graffiti onto storefront shutters, transmitting more Trojan horse–like commercials inside other companies’ ad campaigns,* and even recording and releasing FUBU-branded albums with the artists who helped them build the label.

FUBU is a classic hip-hop success story. Like hip-hop, FUBU is a grassroots D.I.Y. outfit that came up from the streets, remixing existing media into its own pirate material and forging a strong authentic connection with a massive audience. The start-up from Queens now reigns supreme.

Daymond John and the FUBU brand told the story of a movement that lacked power but that was in a position to seize it. He told it so well that he was able to convince stars to endorse his product for free, pulling off stunts that could have wrecked their careers, but instead converted more fans. The hip-hop community made an authentic connection to John’s brand, and FUBU turned that connection into a multimillion-dollar business. If a story doesn’t speak to an audience, they will tune it out. And this is not just a truth in hip-hop: there is a long history of brands losing millions because they failed to do so, while others make billions because they did.

Blowin’ Up Without Going Pop

Let’s look at authenticity through the bottom of a beverage glass. Douglas B. Holt observes in his book How Brands Become Icons, how PepsiCo’s Mountain Dew soda successfully made a name for itself by championing extreme sports and slacker culture, but over a decade it tried three times to co-opt hip-hop, and three times it wiped out and fell flat on its face.

Instead of communicating genuinely with hip-hop, PepsiCo acted like a cultural tourist who didn’t speak the language, looking in from the outside and creating a parody of the culture it observed. First, in 1985, Mountain Dew launched a commercial centered around break dancing and BMXing titled “Bikedance.” It was so far off the mark, it actually caused sales to decline for the next two years. Then in 1993, the drink spawned a hip-hop–inspired but poorly executed cartoon character called “Super Dewd,” a hip-hopping, skateboarding, basketball-dunking buffoon who went down so badly that PepsiCo pulled the entire campaign, limping back to their extreme sport comfort zone.

Finally, in 1998, a fleet of reps in Mountain Dew–branded Hummers fanned out across the country, hanging out in urban areas blasting loud music and offering free samples to teenagers outside schools and malls—a strategy borrowed straight from hip-hop labels who promote records in this way. The hip-hop labels had in turn borrowed this strategy from drug pushers, but unlike drug pushers, Mountain Dew hadn’t established its license to operate.* Dew then shot an ad featuring rapper Busta Rhymes, which placed him, as Holt tells it, “incongruously, in Dew’s world. The spot showed the rapper ice-picking his way up a mountain, dreadlocks and all…. The ad seemed to make fun of Dew’s existing cultural home while failing to do justice to the hip-hop nation, an unfortunate and unintended effect.”

Because they didn’t make an authentic connection with the culture, Mountain Dew didn’t connect with hip-hop’s audience, and the marketing moves alienated their core slacker audience, too. Instead of coming off cool, hip, and down with the kids, Mountain Dew ended up looking like your dad dancing to “Baby Got Back” at a wedding.

Contrast that failure with the way designer water company Glacéau worked with Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson in 2005. Glacéau produces Vitamin Water, a line of colorful drinks enhanced with electrolytes and vitamins. It’s marketed as an upscale, less sugary alternative to soda, popular with gym bunnies, metrosexuals, and the stroller set. Twenty-six-year-old 50 Cent was hip-hop’s favorite cartoon villain, telling street-tough tales of life growing up as a crack dealer. The two brands couldn’t be more different. So how did they work together to create a soft drink that became the choice of a new generation?

The partnership between 50 Cent and Glacéau was forged on authentic connections. It started with a story similar to LL Cool J and FUBU, when Glacéau executives spotted 50 Cent drinking Vitamin Water in a commercial he did for Reebok. They decided to reach out to him, and were surprised to discover how much they had in common.

Again, both hailed from Queens, and a healthy lifestyle was something 50 Cent took seriously; he’d already turned down several offers from companies selling sugary soda and alcoholic drinks. “Being as healthy as I am—I don’t drink alcohol—Vitamin Water helps me live a healthier lifestyle and control what goes into my body,” he explained in a carefully crafted PR statement.

Even though they were both from Queens, there are clearly many differences between a bottled water turned flavor of the month and a crack dealer turned rapper. So to work together, they focused on, to paraphrase MC Rakim, not where they were from, but where they were at.

Both brands were at a similar point in their careers. Despite Diddy’s YouTube claim, 50 Cent was the newly crowned king of commercial hip-hop in 2005. He came up by shifting fifty thousand mixtapes on the streets of New York by himself, to become a one-man brand on a par with Donald Trump or Oprah, and getting shot nine times along the way. The year before, he’d made $50 million without releasing a single record. He had a clothing line; a line of Reebok sneakers (that in 2005 was outselling all of Reebok’s shoes endorsed by sports personalities); and his book, video game, and movie were all hits that year, too. When he released his second album, The Massacre, he told me, “I actually had number one, two, and three in the Billboard charts the week the album came out. I was the first artist ever to do that and I think that says it all.”

Vitamin Water was also a hot young upstart. As consumers shifted away from traditional carbonated sodas to energy drinks and flavored waters, it was climbing a hockey-stick sales curve, growing 250 percent since 2000. “We both grew in a similar sort of way,” said Rohan Oza, senior vice president of marketing for Glacéau, to the New York Daily News. “He is the hottest music star, and we’re the hottest beverage company in the country, so it’s a natural fit.”

By 2005 both 50 Cent and Vitamin Water had both accumulated some serious swagger. This is where Glacéau found a real connection to the hip-hop star, so they decided to capitalize on it. They did so with a sophistication that has eluded most big brands that try to buy their way into youth culture.

Instead of throwing 50 Cent some money and slapping his face all over their products, they negotiated a deal, and 50 Cent bought a small stake in Glacéau. They then asked him to collaborate with them creatively and design a new flavor of Vitamin Water.

The bright pink grape-flavored drink they created, Formula 50, was branded in the same understated way as the rest of the Vitamin Water line. Packaged simply and clinically in one of their trademark oversized medicinal bottles, there is hardly a mention anywhere on the purple label of an affiliation with 50 Cent. This might seem absurd; why align yourself with a celebrity and not shout about it?

If Vitamin Water had branded Formula 50 with images of a guntoting, bulletproof-vest–wearing 50 Cent that looked similar to his album covers, they ran the risk of alienating Vitamin Waters’ core consumers. It also could have alienated hip-hop fans increasingly turned off by corporations trying to sell them products irrelevant to hip-hop culture, using crass hip-hop stereotypes. It made sense for neither audience; it wouldn’t have been real to either of them.

Instead 50 Cent pushed the beverage on his fans covertly, drinking it at shows and subtly slipping it into his 2005 video game Bulletproof, in which a virtual Formula 50 bottle makes a cameo as a health power-up, replenishing the pixilated 50 Cent’s energy level. Back in the real world, a special-release bottle featuring a platinum and purple label dropped in certain stores (which still only mentioned 50 Cent once, in fine print, and had no other logos or photos), released on the hush-hush like a limited-edition sneaker, to celebrate the release of 50 Cent’s The Massacre. It was packaged and promoted to 50 Cent’s fans so they knew it was his drink, but a soccer mom could buy it and have no idea; 50 Cent hid himself in Vitamin Water in plain sight, like a FUBU hat in a Gap commercial.

Vitamin Water then launched print and TV ads for the drink, once again veering away from 50 Cent’s tough-guy image.* Instead they portrayed the drink as a genuine part of the rapper’s daily superstar routine. “Fiddy” was pictured drinking it in his private gym before going into his studio, and sipping some with breakfast as he perused The Wall Street Journal at his Connecticut mansion. Vitamin Water put 50 Cent in the same upscale limelight as the beverage, where together they shone side-by-side as beacons of a health-conscious lifestyle. And 50 Cent was presented as an inspirational figure to both their core audience and his, without compromising either brand’s integrity.

Vitamin Water put together a genuine collaboration that made sense for 50 Cent, Glacéau, hip-hop, and gym bunnies, too. The flavored-water market grew 57 percent in 2005. Vitamin Water grew 200 percent. Coca-Cola bought Glacéau in May 2007 for $4.1 billion in cash.

The Best of Both ’Hoods

In previous chapters I’ve talked about the ideas behind a youth culture, and then looked at how these ideas impacted the rest of society. But with hip-hop it’s impossible to separate the underground youth culture from the mainstream. Hip-hop is still an underground scene, but it also exists in every part of mainstream culture. This has long baffled cultural critics, the same way light baffles scientists by existing as waves and particles at the same time. Hip-hop seems to contradict itself at every turn. Youth cultures usually offer people realism or escapism, but hip-hop sells both.

Hip-hop is filled with gritty, unfiltered stories of poverty, tragedy, rage, and violence, but it’s also a romanticized vision of the free market, bling, and big pimpin’. It maintains a country house, a fleet of luxury rides, and a private jet, but it will never leave the street, and it remains stationed on the corner, hugging the block. You’ll also find it in every middle-class suburb in between, partying in the club, disturbing the peace, or getting cerebral at the coffee shop, while its many cousins can be found in favelas, shanty cities, and slums across the southern hemisphere. It is omnipresent.

Rock can do escapism and realism, too, but hip-hop did something rock never could—it managed to blow up without going pop. It sells a way out of poverty rather than just selling out, painting elaborate pictures of wealth and success, but also by criticizing the system through blunt stories of real-life suffering and violence. In the 1990s, gangsta rap shocked the middle class the same way punk did, but it was effective in getting its message across. Before graphic depictions of inner-city life began to emerge from the West Coast in the late 1980s, many had no idea how desperate life in certain parts of America was (and still is). It was, in the words of Chuck D, “the black CNN.” Since then, as acclaimed hip-hop writer Jeff Chang observed, thanks to hip-hop, “old boundaries between activism and arts blurred.”

Does it glorify violence gratuitously? Without a doubt, and concerned parents, talk radio hosts, and most of all, other hip-hop artists will continue to dress it down for doing so. Hip-hop has no fiercer critic than hip-hop (it also just happens to be its own biggest fan). How is this movement going to be replaced when the antithesis of hip-hop is…hip-hop?

It remains true to itself as an underground movement and a multinational, multibillion-dollar industry in the same instant. In the United States, hip-hop stars rap about buying jewelry and going platinum, while MCs in South Africa talk of exploited workers toiling in platinum mines. Newsstands contain shelves of mass market glossy magazines that document excessive dreams of the lifestyle, while across the street a guy is selling subversive hip-hop literature from a makeshift table. Its contributions to fashion stretch from haute couture to hoochie mama, and it evolved into a scholarly pursuit as easily as it became violent video games and branded bathrobes. How can it constantly contradict itself without tearing itself apart?

Credit Where Credit Is Due

Once again, the answer lies in authenticity. Hip-hop has managed to make connections with several audiences in several different regional and national markets. It works with every scene, sound, and culture it can.

By appropriating everything and authentically connecting to other scenes, hip-hop has gained so much cultural credit, it is now accepted just about everywhere. Nobody in the scene personifies this universal acceptance better than the man who created hip-hop’s first major label and later hip-hop’s first major credit card: Russell Simmons.

As Simmons tells it, he started out hustling drugs and running with a gang in Queens, but he made his fortune selling a lifestyle. “Hip-hop has many different voices, although [it has] a common kind of social, political, and environmental backdrop,” he told me. “There’s so many billions of dollars and there is space available that young people can occupy.” He’s right—but that space is there only because Simmons helped create it. There has been no greater contributor to hip-hop’s worldwide acceptance than Simmons, and he managed it because he believed in hip-hop as a cultural force from day one, and because he aligned himself with great people just as hip-hop aligns itself with great sounds.

Simmons started his career by managing Kurtis Blow, who in 1979 became the first rapper ever to be signed to a major label. Then in 1984, Simmons founded Def Jam Records with a middle-class Jewish kid from Long Island named Rick Rubin. Rubin was a punk and metal fan who liked the energy in hip-hop clubs and saw it as the “black punk.” Rubin was a great producer, Simmons knew how to hustle, and together they signed some incredible talents such as Run-D.M.C. (a group that included Simmons’s brother Joseph, better known as Reverend Run), Public Enemy, LL Cool J, and the Beastie Boys.

Although all these artists fall under the umbrella of hip-hop, this was a diverse lineup, to say the least. Under Simmons and Rubin’s guidance, each act was encouraged to play to their strengths and to incorporate diverse sounds and ideas while always staying focused on the core hip-hop market. Run-D.M.C. collaborated with rock band Aero-smith and sold three million copies of “Walk This Way.” LL Cool J (short for “Ladies Love Cool James”) was hip-hop’s original ladies’ man. Public Enemy did political and the Beastie Boys were rapping and being white at the same time, ten years before Vanilla Ice officially invented it. All of these Def Jam artists are still popular today.

Simmons had always seen hip-hop as more than music, and went on to sell it in many other areas. Today Simmons has a hand in the movie business, fashion, television, energy drinks, online, jewelry, hiphop/yoga workout DVDs, financial services, and more, all underpinned by hip-hop culture. He’s managed to keep an authentic connection to his core hip-hop audience while keeping an eye on the mainstream, in order to stretch his brands like limos and broaden his markets without losing fans along the way.

Swaggernomics

Simmons inspired a generation of hip-hop entrepreneurs; then again, hip-hop was always an outspoken advocate for entrepreneurship. No other subculture has ever been as celebratory or savvy when it comes to the free-market system. Rappers don’t just talk about getting money, they’ve become some of the most versatile businesspeople in America. When producers such as Dr. Dre, Timbaland, and Lil Jon work on tracks for other artists, they don’t just produce the records they make, they also brand them, appearing in the videos and singing hooks, often cross-promoting their own product lines at the same time. For commercial hip-hop stars, having several side hustles is as important as having several clean pairs of kicks.

Hip-hop is a game of braggadocio, and conspicuous consumption is no longer enough to impress. The more you can successfully build and extend your brand and still manage to keep it real, the more you can exaggerate your swagger. Diddy didn’t invent the remix, as he claimed on his 2002 album We Invented the Remix. But he became a remix, permanently rebranding himself and extending his Bad Boy label into one acting career, two restaurants, three apparel lines, several lucrative licensing deals, and fourteen different types of “luxury sneaker.”

Meanwhile, rapper Snoop Dogg’s endorsement endeavors make most logo-covered professional athletes look like anticorporate prudes. Aside from the requisite clothing line, sneaker deal, and Hollywood career most rappers now feel naked without, “Bigg Boss Dogg” has his own brand of pornographic DVDs, malt liquor, foot-long hot doggs, a skateboard company, a youth American football league (the Snooper-bowl), and a line of action figures, not to mention endorsing everything from mobile phones to scooters to “Chronic Candy.”* A more diverse line of side hustles is hard to imagine, but Snoop pulls it off by endorsing products that reflect his personality. Hip-hop artists create business empires as a form of self-expression the way the rest of us build MySpace pages.

Hip-hop instills passion in its fans and then demands participation, making entrepreneurs out of even the most reluctant. When artist and producer Pharrell Williams was growing up in Virginia, hard work just wasn’t his thing; he was fired from three separate McDonald’s restaurants. “I didn’t give a fuck, just as long as I didn’t have to work,” he told me in 2004, lounging in London’s exclusive St. Martin’s Lane Hotel. But the hip-hop bug bit him, and Williams worked so tirelessly to refine his craft that by 2003, 43 percent of the records played on U.S. radio that year were his handiwork. Since then the Grammy Award–winning producer turned one-man band has been inspired to launch a sneaker line, two clothing labels, and purchase a handful of Fatburger fast-food restaurant franchises. “When you love something so much,” he says, “and are that passionate about it, it won’t feel like work. Lazy people just gotta find their passion, man, that’s all.”

Hip-hop is not just about doing it yourself, but also about working damn hard for yourself. Hip-hop breeds its success stories in-house, influencing its fans to follow their example. It is an extension of the punk mind-set that retains rebellion and hedonism but constantly reminds its listeners of the importance of staying on their grind and working hard. Many artists and fans don’t like the fact that money has changed hip-hop. But hip-hop also has changed how many artists, fans, and corporations think about making money.

The business acumen behind hip-hop and the fact that it made entrepreneurship cool is one of its strongest attributes. Georgia-based MC Young Jeezy constantly reminds fans he is about the business of music rather than music itself, asserting, “I’m not a rapper, I’m a motivational speaker.” Part of hip-hop’s appeal is that it is viewed by many as a way out—a path to success that bypasses conventional routes to the top, routes that remain closed to many. Hip-hop offers sound advice on marketing, distribution, PR, promotion, and more. No other music scene in the history of the music business has been quite so obsessed with the business of music. Ninety-nine percent of aspiring MCs won’t become the next 50 Cent, but they will learn something about building a brand, and they’ll gain practical experience that isn’t available in any classroom. These days the first thing an aspiring MC may write is a business plan.*

Successful rappers have become multinational corporations. In 2005 Jay-Z, whose current business interests include, among other things, Roc-A-Fella records, Roc-A-Wear clothing, a line of luxury watches, S. Carter sneakers, the 40/40 Club, and a stake in the New Jersey Nets basketball team, hit this particular nail on the head. He dropped a line on the remix of “Diamonds from Sierra Leone” by Kanye West, saying, “I’m not a businessman/I’m a business, man/So let me handle my business, damn!”

He was also referring to the fact that he had recently been made president and CEO of the record label he had been signed to for years: Def Jam Records. The move looked like a publicity stunt at first, and this was not lost on Jay-Z. “I know people think that this is a vanity job or that I’m the guy that just brings in talent and I’m out of the office three months a year and I only come in once in a while, you know, like the real president,” he joked to The New York Times. “But yes, I’m really there.” It may have seemed crazy, but it makes perfect sense. If rappers are experts at extending brands, as Jay-Z certainly is, why not hire a rapper as CEO? And why stop at record companies? Could Russell Simmons head up GlaxoSmithKline? Should 50 Cent take over Blackwater?

But these are not the most pressing questions we need to ask about hip-hop’s destiny. Hip-hop has forged such a strong connection with so many, it can create change like no music scene before it. “I don’t think there is any place it doesn’t exist,” says Daymond John of the movement he grew up with. “Hip-hop artists are addressing the U.N. It could actually overthrow governments. This is the communication of the poor. Music is one of the most powerful ways people communicate with each other. There is no limit to this.” Hip-hop has proved to be a great way to generate money, but it’s now in a position to generate some serious social change, too.

Don’t Believe the Hype

Yes, hip-hop is a commercial juggernaut. It is a high-gloss, well-oiled, intelligent commercial machine able to transform to stay on top like Optimus Prime. But in addition to conquering the commercial sphere, it has simultaneously become the common voice of people around the world. It’s a way to express ourselves in common terms, something we’ve been trying to do since the Tower of Babel fell.

Commercial hip-hop is often perceived as nothing but an empty, misogynistic, violent culture obsessed with hos, bling, and little else. In contrast, the baby boom generation remembers themselves using rock ’n’ roll to shake things up in the sixties and end the Vietnam War, as we are now reminded in TV ads for retirement plans. The criticism leveled at commercial hip-hop is justified. Rock ’n’ roll certainly changed the world. But the dirty secret is that generation hip-hop is doing it even better.

Many baby boomers consider this generation apathetic compared to themselves. But before the war in Iraq even started, the hip-hop generation had organized the largest protests in history against the decision to go to war. Between January 3 and April 12, 2003, a total of thirty-six million people across the globe took part in almost three thousand protests.

According to hip-hop writer Jeff Chang, evidence for the hip-hop generation’s growing political and social clout also can be found in 2004 U.S. election data. He wrote in 2006, “4.3 million more voters between 18 and 29 came to the polls than in 2000, a surge unseen in decades. In other words, the 2004 election marked a historic moment, the electoral emergence of the hip-hop generation.” Chang also cites studies such as the UCLA freshman survey that points out that “the hip-hop generation’s rate of participation in voluntarism, in political protest and in activism on a wide range of issues is much higher than that of the baby boomer generation during their youth…. The myth of an apathetic generation—one even upheld by some of our youngest public intellectuals—is one of the most baseless and insidious lies of our era.”

It’s Not About a Salary, It’s All About Reality

Hip-hop has been right on the money when it comes to building businesses, however, the corporate hustle hip-hop loves so much isn’t always about keeping it real. But many hip-hop entrepreneurs are Punk Capitalists; they are social entrepreneurs. In the spirit of keeping it real, hip-hop entrepreneurs use their celebrity status to benefit the communities that put them in the limelight in the first place.

Russell Simmons has long looked at hip-hop’s influence in this way. Among his more recent projects, he launched the Rush Card—a Visa debit card aimed at the forty-five million Americans whose credit situations mean they can’t qualify for a credit card, as well as a range of conflict-free diamonds.* “The African American community chooses what cool jewelry happens in the world,” he said to me in 2004 before the launch, “but none of us are in the bling bling business. If we gonna buy bling bling, then we gotta bling all the way. I don’t know if that industry is gonna like us highlighting the conflicts going on there, but I don’t do shit for money.”

Another great example is sportswear and sneaker brand Starbury, owned by basketball star and hip-hop fan Stephon Marbury of the New York Knicks. Hip-hop has long harbored an unhealthy fetish for sneakers, from Run-D.M.C. recording “My Adidas,” to kids getting shot for their Reebok Pumps in the 1980s, to people camping outside sneaker boutiques all night to cop a limited-edition pair of Nike Dunks.* The more sneakers are hyped before their release, the higher the prices have climbed.

Marbury grew up obsessed with basketball, under hip-hop’s shadow in the housing projects of Coney Island, Brooklyn. But top-of-the-line basketball shoes, manufactured cheaply and targeted at kids from low-income families like his, were way out of his league, at $100 to $200 a pair. When Marbury became an NBA star he was, like many NBA stars, offered multimillion-dollar endorsement deals from these same companies. But Marbury saw an opportunity to do something different, a chance to take keeping it real to a whole new level.

Teaming up with low-cost retail outlet Steve & Barry’s, Marbury developed his Starbury brand of sneakers and apparel, which retail at rock-bottom prices. The basketball shoes on sale at Steve & Barry’s for $14.98 are actually the shoes Marbury wears on the court. “Now parents can afford to go to a store and buy five kids something…and the kids can feel good about it, and not feel like ‘I’ve got something on that’s wack,’” he says in a promo video on Starbury.com. “We’re just flippin’ it and turnin’ it around.”

Starbury proved to be a slam dunk. At Steve & Barry’s stores, demand is so high there are signs up restricting each customer to just ten pairs of sneakers from the Starbury range per day. With no big-name sports brand behind him, Stephon Marbury managed to create the realest sneaker ever to emerge from hip-hop culture.

Paying Forward

Hip-hop mastered the art of the sustainable sellout through the notion of keeping it real. It instilled a focus on giving back to the community in people such as Stephon Marbury and Russell Simmons, because giving back has been an integral part of hip-hop since its birth in the Bronx.

Hip-hop is once again becoming a powerful form of collective action, as it was at its birth in the 1970s, only this time it’s on a much larger scale. “It’s always about what we are giving back,” says Russell Simmons. “It’s important that we acknowledge that.” Rolando Brown, executive director of the Hip Hop Association,* agrees, asserting that it’s now time to start spending hip-hop’s cultural capital. “We realize there is an opportunity to be change agents,” he explained to me over lunch in Harlem. “What we are seeing right now is a lot of people who are tired of the same old song, but will soon have a real opportunity to do that thing.” “It done got bigger than us,” Diddy told allhiphop.com in 2006, clearly in a more reflective mood after digesting his burger. “It got way bigger than just us. We gotta be laying down the foundation for everybody to come after us.”

Diddy’s right. When mainstream brands interact with hip-hop—or any other youth culture, for that matter—it works only when the brand is seen to put something back into the culture. Because of its incredible commercial success, increasingly hip-hop is coming under pressure to participate in the world the way it wants the world to participate in hip-hop. It is hip-hop’s time to give something back.

This is happening in a number of ways. Hip-hop megastars are starting charities and nonprofits just like other multimillionaires. Diddy runs Daddy’s House, a foundation providing funding and education for underprivileged youths, while 50 Cent has shifted his focus from pieces to weight, launching a child obesity initiative. Russell Simmons now devotes most of his time to philanthropy, as founder of the Hip Hop Summit Action Network and the Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation. While this in itself doesn’t set hip-hoppers apart from other celebrity philanthropists and corporate giving programs, it is a sign of a sleeping giant stirring. Hip-hop is slowly waking up to the fact that it is powerful enough to start revolutions.

Hip-hop has always been a radical disrupter, incredible entrepreneur, and social organizer, but as it increasingly uses these three skills together for social purposes, we may see changes as radical and as exciting as hip-hop’s commercial success stories. Hip-hop power brokers have started to jump on the world stage. Russell Simmons was inducted as a goodwill ambassador in a U.N. campaign against global hunger in 2006, while Jay-Z forged a partnership with MTV and the United Nations to draw attention to the millions around the world who do not have access to clean drinking water. “When Jay-Z talks,” noted MTV News, “his words reverberate all around the world.”

It seems that hip-hop has been chosen to lead. As S. Craig Watkins notes in Hip Hop Matters, “The hip-hop generation may soon be the most powerful constituency since the religious right in America.” Whoever the first hip-hop president may be, the real power in the movement is not the few at the top leading, but the billions underneath.

Planet Hip-Hop

Former U.N. secretary-general Kofi Annan once described hip-hop as a language. Recognizing its power as a social force, the United Nations included hip-hop in its Millennium Development Goals as a tool to reach and uplift millions of young people around the world, organizing the Global Hip-Hop Summit and enlisting the help of artists such as Snoop Dogg, Gangstarr, and others on several U.N. projects. This is but a glimpse of the movement’s potential.

Hip-hop is a common language and a political motivator creating cross-cultural understandings that have never before existed. Hip-hop around the world is influenced by American culture, but many local varieties exist because hip-hop allows itself to be customized in local markets to better suit local tastes.

Within America there are dozens of variations from state to state, from the East Coast to West Coast sounds of yore to southern subgenres such as crunk or chopped and screwed, hyphy in the Bay Area, and Miami bass in Florida. Meanwhile, outside of the United States, Miami bass’s cousin baile funk rocks the favelas of Rio. In the Dominican Republic, hip-hop fused with merengue to create meren-rap. It collided with Jamaican dance hall and landed in Latin America as reggaeton. In Europe, France has the second-largest hip-hop market in the world. German hip-hop regularly hits the top ten, while the United Kingdom has grime, and bespoke European scenes stretch across the Continent all the way to Russia. Local adaptations flourish from Shanghai to Seoul to Tokyo. You can hear hip-hop colliding with the bhangra music of northern India and Pakistan when you listen to the hybrid known as desi beats. Scenes are spreading through Australia, intertwining with Maori cultures in the Pacific Islands and moving across to the Middle East, where some Israeli and Palestinian MCs are working together. Regional variations such as Ghana’s hip-life scene have weaved themselves into African music as hip-hop negotiates Africa’s complex tribal matrix of indigenous cultures, rounding the cape and fusing with house music to become a sound known as kwaito. “Within the context of hip-hop culture, there are so many places people can meet,” says Rolando Brown of the Hip-Hop Association. “Hip-hop gives us an opportunity to connect with people that we did not have twenty years ago. It’s undervalued, because it’s become a clichéd concept, ‘Oh, hip-hop is unifying people, so what?’ No. It is. That’s what it is. That’s amazing and we have to recognize that.”

Hip-hop pioneers in the United States such as Afrika Bambaataa always had a global vision for the movement, and it has developed by incorporating local insight into that vision. Hip-hop superstars have managed to connect authentically to people on every continent, even in countries they have never visited. Rozan Ahmed, a U.N. public information officer currently stationed in the Sudan and who was previously my deputy editor at urban music magazine RWD in London, sees a strong link between the hip-hop world she was immersed in there and the sentiments of young people she now works with in Africa. “It’s uncanny how people living in the bush out here can relate to hip-hop,” she tells me. “They relate because they familiarize, they see their dream of escape. It brings hope without even trying to.”

For the first time ever, it would seem the world has a youth movement everyone can relate to. “It is one of the only subcultures that still represent rebellion and a sense of self,” continues Rozan. But is hip-hop really big enough to make a difference? “If certain artists in places of real power lay off the hip-hop hos and platinum watches and really utilize their influence on so many millions of frustrated kids, then yes—perhaps. I’ve seen 50 Cent signs in the middle of nowhere, deep in nothing but jungle. I don’t even know how those people managed to hear 50 Cent. Can you imagine the impact 50 could make if he took part in, say, the U.N. International Peace Day? Do you know how many more of the people who need to be peaceful would pay attention?”

Darfur, Sudan, 2006

© Jamie-James Medina

“Hip-Hop Better Wake Up”

Missy Elliott opened the track “Wake Up” with this statement in 2003. She was not talking about hip-hop as a language that can unite the downtrodden, but the dire state of commercial, mainstream hip-hop. The wake-up call came in 2006. Hip-hop sales in the United States fell dramatically, down 21 percent from 2005. For the first time in twelve years, there wasn’t a single rap album in the top ten bestselling albums of the year. In a poll of African Americans by the Associated Press and AOL–Black Voices conducted that year, 50 percent of respondents said hip-hop was a negative force in American society. According to a 2007 study by the Black Youth Project, the majority of young people in America think rap has too many violent images. Hip-hop artist Nas released an album titled Hip-Hop Is Dead.

After three decades at the top of the cultural heap, it seems that hip-hop is starting to lose its footing. It is the sound track to our current economic paradigm, but the relevance of both is waning. In its relentless pursuit of the finer material things in life, hip-hop was the perfect accompaniment to late-twentieth-century capitalism. But the economic model behind hip-hop is changing.

The outlook of both our economic model and commercial hip-hop became blinkered. The way many artists evangelize drug dealing, violence, and the pursuit of money, no matter what the cost, is a message critics perceive to be damaging. Critics of our economic model feel the same about the way neoclassical economists paint abstract pictures of the world. Neoclassical economics is based on an irrational belief that unlimited growth can solve everything, without taking into account the long-term effects or social costs of such growth. This business model doesn’t work in a world of finite environmental resources, only in some imaginary utopia. This business model is about as sustainable in the real world as the party at a hired mansion full of hired girls in bikinis depicted in your average rap video.

Like commercial hip-hop, neoclassical economics is increasingly coming under fire from the inside. In 2006 hip-hop fans rebelled with their wallets. Real has begun to recognize real in the ivory towers of academia, too. The Post-Autistic Economics (PAE) movement was conceived in 2000, based on the work of a Sorbonne economist named Bernard Guerrien. Today some of the most talented minds in economics around the world are challenging the disconnect between mainstream neoclassical economics and reality. It began with a group of students in France who branded the reigning neoclassical dogma “autistic.” As it is with sufferers of autism, they argued, neoclassical economics is intelligent but obsessive and narrowly focused, disengaged from the real world. It advances its cause by making us believe in a set of imaginary conditions, like a rapper who pretends he’s a crack dealer just so he can sell more records.

“We believe that understanding real-world economic phenomena is enormously important to the future well-being of humankind,” PAE representative Emmanuelle Benicourt told Adbusters in 2006, “but that the current narrow, antiquated and naive approaches to economics and economics teaching make this understanding impossible. We therefore hold it to be extremely important, both ethically and economically, that reforms like the ones we have proposed are, in the years to come, carried through.”

The PAE movement spread from the Sorbonne to Cambridge to Harvard to every major Ivy League school in the United States and academic institutions around the world. It now has nearly ten thousand members in 150 countries. The movement regularly makes headlines internationally, arguing that, as the great economist Milton Friedman once said, “Economics has become increasingly an arcane branch of mathematics rather than dealing with real economic problems.” Dumping toxic waste in poor countries, sweatshop labor, war—all these things make perfect sense economically. They don’t make much sense for the people they affect. Glorifying drug dealing, threatening people with gun violence, demoting women to garden tools—all these things make perfect sense on your average commercial hip-hop record. They don’t make as much sense to the hip-hop fans switching off in increasing numbers.

It is this unencumbered pursuit of growth that has polluted hip-hop so much. The influence of risk-averse major labels and radio consolidation helped homogenize the culture. Major hip-hop releases have played it safe by sticking to a chart-friendly formula of misguided masculinity and misogyny. As longtime hip-hop fan Dart Adams wrote on his blog Poisonous Paragraphs in 2007, “I used to learn from the hip-hop I grew up on. It was filled with uplifting messages for the youth and had more than enough variety and artistic merit that you couldn’t possibly generalize or pigeonhole it into being one monolithic thing. Ever since it became big business and got away from the basics, it has gotten progressively worse. How can these outsiders complain about the current state of rap music when they’re part of the reason it’s in the state it is now? Why can’t they recognize their own double standards and hypocrisy in regards to narrowcasting hip-hop culture?”

Hip-hop can bring attention to many of the problems the world has, but first it needs to address the problems within itself. This youth culture obsessed with authentic connections needs to get real again. The same goes for our economic system. If hip-hop is to remain a rebel, and if neoclassical economics is to continue to govern, both need to wake up.

The End?

Despite its recent commercial woes, hip-hop still has global appeal, and more potential political power (albeit untapped) than any White House administration. Hip-hop has earned a license to operate on every continent by making authentic connections to people and markets the same way it did back in the Bronx. By appropriating everything in its path, it can and has built new brands, sounds, and scenes, which are all able to coexist under its inclusive umbrella. It encourages its audience to put back into the communities they take from. Tracing back hip-hop’s path to world domination reveals a way to make a pile of money, or a big difference, or both.

The movement wrote a new chapter in American history, but could be the history of the world’s next act. Just like the rest of society, hip-hop is being forced to make a transition because of the forces of Punk Capitalism. Hip-hop’s future is uncertain, but one thing is for sure: hip-hop has expanded so far and wide that it is clear it has more than one destiny.

I predict it will have no fewer than three.

The Good Ending

The utopian vision of Afrika Bambaataa and the ancient prophets of hip-hop will be realized, and social harmony will be achieved through two turntables and a microphone. The sales blip will be overcome, and it will continue commercially into the stratosphere, until Snoop has his own airline that guarantees you stay high, and Diddy and Burger King together colonize the moon.

Rap museums and hip-hop golden-era nostalgia radio stations are already here, yet nothing has dethroned it. It will remain a voice of the downtrodden, a sound track that crosses cultural and national boundaries. It will mature from its difficult adolescence into a broad-minded thirtysomething, and it will grow tired of degrading women and bragging about violence, instead focusing on the bigger issues it faces. It is more than thirty-five years old, fully grown and ready to assume responsibility. It is the world leader waiting in the wings ready to empower the planet, all of us united under a groove.

Word to your mother.

The Bad Ending

Hip-hop took over from the inside, like a wolf in sheep’s clothing. But now it’s just a herd of sheep dressed in adorable little limited-edition wolf outfits with dorky matching sneakers and fitted hats. The politics, rage, and rebellion of groups such as Public Enemy have been replaced by a generation more concerned with Public Enemy member Flavor Flav’s VH1 reality show Flavor of Love, confirming hip-hop’s worst fear: a wack planet.

DJ Premier and graffiti artist HAZE summed it up best on their 1997 underground mixtape New York Reality Check 101: “It is the underground that put you on, and it is the underground that will take you off.” Hip-hop forgot where it came from. It’s about time it got whacked.

Commercial hip-hop no longer feels like it’s on the side of the downtrodden. It was once a spanner in the works; now it’s just another part of the machine, increasingly self-absorbed and ignorant of the world around it.

Commercial hip-hop went from angry young activist to comfortable, obedient citizen, to bloated, corrupted corporate carcass. Hip-hop sold its soul and is dying slowly, begging to be put out of its misery by a fitter, leaner, younger movement. Let’s face it: at nearly forty, it’s embarrassing to see it out there in the clubs still pretending it’s a kid.

It has become a ridiculous pantomime so far removed from the culture that created it that all meaning has disappeared. Its basic premise that selling out is okay has left it with nothing more to sell. Soon hip-hop will be so watered down, the most threatening man in the game will be Turtle from Entourage.

Stop kicking it. It’s already dead.

The Scooby-Doo Ending

Not so fast! Hip-hop has always played at being the cartoon villain, but under its crass, commercial mask is a movement that’s making a difference. Hip-hop has many masks left to shed, and it will never quit changing its identity. It will still be here in a decade, but it may be unrecognizable to its audience today.

Disco shed its skin and became house. Under the crusty chassis of classic rock lurked punk. Change is the only option for the chameleon that is hip-hop because that’s how it has always responded to its changing environment. The voices of change are already getting louder. Bling will become passé, rappers will retire, but the real forces that drive hip-hop—telling authentic stories of hope, suffering, hedonism, alienation, and a desire to create change—will not.

The notion of hip-hop as a way out and as a change agent will continue to appeal to people around the globe. What it evolves into may no longer call itself hip-hop, but that’s fine. Hip-hop has always acknowledged that the ideas behind it are bigger than hip-hop itself. Hip-hop’s new disguises will be many and varied, operating in such a way, as we shall now see, that you may not notice their existence at all.