THEODOR W. ADORNO AND ARNOLD SCHOENBERG are two of the most uncompromising figures of the twentieth century. Photographs of them in old age witness the clenched stubbornness of an African fetish reappearing in their faces. The intensity of this spirit shaped and penetrated every detail of their work. In his Theory of Harmony, for example, it compelled Schoenberg the educator to disclaim the book’s massive pedagogical effort. After four hundred pages of careful and sometimes bombastic instruction, reasons for the book are increasingly met by counter reasons, until the two sides come to grips in a locked tangle. At one point Schoenberg goes so far as to reject craft—the entire content of the book—as a standard of composition. Authentic technique is, on the contrary, he says, occult knowledge. He confronts himself with the challenge that this hermetic ideal poses to what he has written: “Someone will ask why I am writing a textbook of harmony, if I wish technique to be occult knowledge. I could answer: people want to study, to learn, and I want to teach.” Having driven himself into a cul de sac of his own manufacture, the only escape route he permits himself to imagine is further self-resistance.1

This is an eccentric process, but the passage tips the hand on Schoenberg’s occult knowledge, which he clearly did not consider unteachable. In fact he constantly demonstrated his basic sorcery in composition class. Once, for instance, having demolished, phrase by phrase, the blackboard exercise of the precocious teenage composer Dika Newlin, he turned to the other students to explain the logic of his coup de grace, as he wiped out a final measure of eighth notes. Class, “do you know why I do not let her use eighth notes? . . . Why, because she wants to use them!”2 Schoenberg thought this funny, and in its own way it was, and still is. But the technique recommended—which permits giving only under the auspices of taking away and requires that one hand always be ready to undo the work of the other—is keyed to the most rapacious demands of twentieth-century composition. For it is not possible to do justice to the experience of this century without knowing how, literally and in the same instant, to block the scream as it occurs. In Schoenberg’s “A Survivor from Warsaw, for Narrator, Men’s Chorus and Orchestra” (opus 26, 1947), German soldiers, before dawn, throw open the sewer where Jews, asleep, are hiding. But even the first moments—the orders shouted, the searchlights—are hard for the ear to follow, let alone describe. The narrator provides the only report of the event, which he relives as one of a haggard crowd as it is driven out of hiding and provoked into a stumbling fast march in the street. He does not know what is or is not dream as the soldiers wade into them and he is clubbed down. The chaos and shattering of the narrator’s own perceptions deprive the listener of any objective recourse. Listening becomes the realization that one’s head has been grabbed from behind and dragged underwater. Everyone having been knocked to the ground, the sergeant—maybe to save bullets—orders their heads smashed. In the concussive instant that the rifle butt strikes the narrator’s head, however, we do not, and could not possibly, hear a scream. The subjective form of the report prohibits the event being registered externally. Instead, the sound that must have occurred is documented only by a muffled, suddenly slack and hollow peacefulness that suspends the recurrent heart-spasming alarm motif that functions throughout the cantata in ostinato. There is perhaps no other composition, no other art work, in which fright and hope become comparably identical in the moment that they vanish. The power of the composition depends on this moment. The panicky inconsolableness of history ignites in this stifled, imploded instant, whereas any scream would have provided the rationalization that it might have been heard.

I

Schoenberg’s intransigence is easily lost from sight in America, where the edifice of New Music—to estimate its cultural magnitude—would be diminutively tented by the League of Professional Bowling, itself one of the lesser sports. Yet Adorno’s work is on this same horizon even more recondite than Schoenberg’s, and as a person he was ultimately more self-protective and austere. Compared to the many vignettes that circulate about Schoenberg, funny classroom stories do not seem to exist about Adorno. Likewise, where Schoenberg’s letters have been a major source regarding all aspects of his life, Adorno took considerable precaution to keep his personal correspondence out of public hands for decades after his death, when—as he rightly feared—it would be used biographically to dilute his work. He spoke by starting at the top of a full inhalation, which he followed down to the last oxygen molecule left in his lungs, and his written style perfected page-long paragraphs hardened to a gapless and sometimes glassy density, as if the slightest hesitancy for an inhalation or any break for a new breath would have irretrievably relinquished the chance of completing the thought. Every one of his stylistic peculiarities was defined by the effort to maintain a moment of critical, historical self-consciousness in opposition to mass culture. This is why his work consistently draws the animus of cultural resentment. For, without flinching, he unmasked the substitute gratifications and betrayals of contemporary society. A population that knows perfectly well that it lives in the service sector of the culture industry will not soon forgive him for putting his finger on what people jockey for as they crowd in line for a new film—“people watch movies with their eyes closed and their mouths open”3—or for revoking the sensed prerogatives of stardom—mass culture’s universal bestowal—by showing that what scintillates in glitter is powerlessness: “he who is never permitted to conquer in life conquers in glamor.”4

II

Adorno and Schoenberg of course are related more integrally than comparisons demonstrate. In Philosophy of New Music Adorno marshals the resources of the entire theodicean tradition of German idealism—the Kantian justification of empirical, practical, and aesthetic judgments, the Hegelian expansion of the transcendental deduction to comprehend the rightness of the universe—on behalf of the justification of an irreconcilable music. He shows that this isolated music had, in the strength of its isolation, become a singular repository of critical historical experience. Adorno does not deduce this position. On the contrary, his thinking originates in this musical experience, and he devoted his life to its elucidation. What distinguishes Adorno’s efforts in this from almost the whole grim genre of aesthetics is that, whereas it generally demands either systematic philosophers who are deaf and blind or effusive admirers of Beethoven’s triumph, Philosophy of New Music is a defense of Schoenberg’s work that presents New Music’s own philosophy; the study aims to carry out conceptually the historical reflection implicit in the music and to raise this reflection to the point of the music’s self-criticism. Insofar as Schoenberg’s music is a dissonant order, Adorno’s work is fundamentally the philosophy of dissonance. Only because Adorno was constantly following the traces of his own sensorium through this music was he able to complete this Hegelian project.

III

The central thesis of Adorno’s aesthetics is that art becomes the unconscious writing of history through its isolation from society. In Philosophy of New Music Adorno details the immediate object of aversion from which modern art and Schoenberg’s music withdrew. There he writes that just as abstract art was defensively motivated by its opposition to photography—the mechanical art work—Schoenberg’s music developed in “antithesis to the extension of the culture industry into music’s own domain.”5 In that Adorno took the side of this music against the culture industry, it can be assumed that he would hardly have made himself more popular at a rock concert than at a conference on Schoenberg entitled “Constructive Dissonance.” His Krausian ears would have recognized in this title the intention of providing sounds that literally dug a moat around themselves—music that will never be heard in any hotel elevator—with the requisite positive glow of popular culture. Just as the latter makes sure its monsters turn out cuddly, “Constructive Dissonance” puts a finger out to give a tickle under the chin: “See, those nasty sounds aren’t so bad. You don’t put them on to play at bedtime, but they want to help, too.” Whatever this conference’s intention to hear and think Schoenberg anew, in Philosophy of New Music Adorno writes that the conciliatory gesture—such as is unmistakably lodged in the phrase “Constructive Dissonance”—was the sign that led the historical retreat from Schoenberg’s music: “Such conciliation to the listener, masking as humaneness, began to undermine the technical standards attained by progressive composition.”6

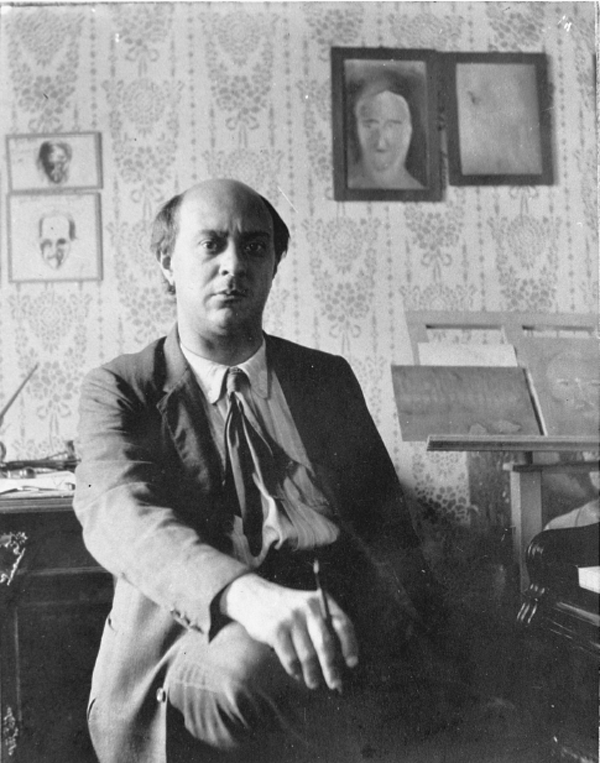

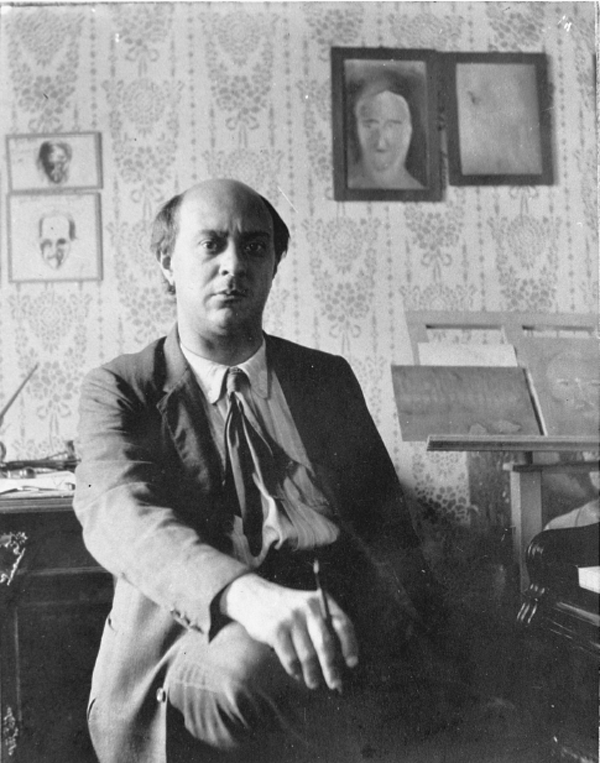

Adorno’s criticism would not have stopped with the title. The conference brochure itself documents the formula for the translation of modern art into mass culture; there in the center of a paste-up of photographs of famous people meeting famous people, Schoenberg cavorting with Kokoschka, a picture of Schoenberg playing table tennis, is a photo of the composer seated in front of a wall of his paintings. While the effort of these well-known paintings is to break through the visible world, to defeat its webbed replicative patterns of illusion, the steady narrative distance of perspectival space, and in opposition present a deposition of isolated subjectivity, the photograph—the amateur and illusory medium par excellence—with its limited powers of focus, contrast, and construction, its unshakable normalization of optical distortion, patches over this content with a melodramatic, stereotypical image of Schoenberg’s face, half in darkness, half in light. And however much the paintings themselves struggle to force their way into the present, the photograph embalms each moment with stasis as a dull sign of an irretrievable past.7 This irretrievability is a fundamental source of its mass culture appeal, because the past that is shaped is anecdotal and sentimental. Every photograph is equally old—even one snapped a second previously—and calls for the same identical tear to be shed on its behalf, the “I knew you when” that all photography hums. An amnesiac’s historiography is created: the need for continuity in time is fulfilled while assuring that the impulses of time remain at a neutral, unshifting distance. If popular music sings of sentimental journeys, the conference brochure photography promises a sentimental conference. And this promise is made good by the actual conference organization into three parts: contexts, interactions, and reception—which could be deduced from the advertisement. “Contexts and Interactions” are to provide a photograph of Schoenberg in the historicist “back then.” This is followed, plausibly enough, by dredging for bodies, that is, with “reception,” a concept that, however the phenomenologists doll it up, surfaces on the palate with such enthusiasm and legitimacy only because it derives from the sensorial order of radio and television.

IV

Glossed by mass culture’s carefully managed populist eye, the continuous claim throughout Adorno’s writings to emphatic musical experience—particularly that of Schoenberg’s music—has often been grounds for shrugging off his social criticism as elitist. This is only secondarily because of mass culture’s allergy to New Music. More important is that both New Music and Adorno are assumed to be representatives of the world of the symphony hall. Insofar as this is the perception, the rejection is not altogether unjustified. If music becomes important as the voice of the voiceless, its symphony hall performers, sponsors, and auditors occupy almost exclusively social positions that gain from the voiceless remaining so. Symphony hall is not shy about this class allegiance, with its playbill of aperitifs and perfumes, an audience of scions in swagger fashions, opera lovers coasting by like ocean liners wrapped in camel-hair overcoats, and a conductor who, whenever he circles from the orchestra to deliver his bows, reveals his aristocratic bearing to be that of a majordomo. Any doubts as to whom these performances are for is dispersed by the San Francisco Symphony, which each year offers subscribers a selection from the Mercedes Great Performers Series and the opportunity to attend BankAmerica Foundation preconcert talks. Popular music fans correctly recognize that they are not invited to these events. But the resentment felt blocks recognition of how much the two worlds have in common, from the sequined dresses to the fame of powerless dukes, kings, and princes, to the inevitably glossy, repetitive performances. Symphony hall and popular music are not the different substances their audiences are encouraged to believe them to be, but different layers of mass culture.

It is only because so-called classical music has been progressively absorbed as one layer of popular culture that it is difficult to realize that Adorno took the side of emphatic music against symphony hall, where he found this music neutralized. He did not, however, consider this neutralization simply adventitious. On the contrary, through its beauty, emphatic music participates in its commercial neutralization, and Adorno wanted to show how the direction of music itself was toward overcoming this neutralization through its internal critique of beautiful semblance. Schoenberg was, in his opinion, the key figure in this transformation of music.

V

A recent San Francisco Symphony performance of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony condenses these issues and makes a bridge to Adorno’s analysis, in Philosophy of New Music, of Schoenberg’s achievement. At a BankAmerica preconcert talk, in fall 1991, the contemporary composer Christopher Rouse—who is a pop music aficionado—introduced Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, a work, as Rouse mentioned, of special importance to Schoenberg’s group. Rouse’s introduction is of interest for what is characteristic in it, much of it owed directly to Mahler’s own programmatic comments. Only a condensed sentence of fragments from his introduction, taken up in medias res, needs paraphrasing to bring this familiar genre of music appreciation to mind: In the theme of the third movement, Rouse explained, Mahler announces his towering love for Alma. And in the finale, the hammer blow of fate sounds for the third and last time, presaging the final disaster that would befall the composer the following year.8 Just as moviegoers watch their stars illustrated by the role performed, this introduction to the Sixth Symphony obeys the constitutive limits of mass culture—simulation and portrayal—and converts the music into a snapshot of the great man’s life. It sets the music as an event back behind the white border of that never-never land where fame keeps its trophies.

The music itself, however, is hardly content with the role of portraying Mahler’s life. And it is possible that members of the post-talk audience sensed something of this as they craned their heads above their seats to see these blows of fate struck. In Mahler’s Sixth these sounds are performed not by the plausible kettle drums but by a sledge hammer. This is, of course, not one of the spiritualized instruments of the symphony orchestra, for the percussionist cannot help but emphasize the struggle to fit the blow of a fifteen-pound hammerhead to the beat. Yet these three blows, programmatically conceived as three blows of fate, go beyond the programmatic. The hammer blow of fate becomes fate the hammer blow; no longer the portrayal of fate but the leveling impact itself. And whatever the force delivered to the subjectivity that stirs in the music, this extra-aesthetic sledgehammer delivers a blow to the fictional order of music altogether. If the various introductions of sections of the orchestra seem to occur without reference to actual time, the three hammer blows break through the autonomous temporality of music each with the intention of notching the clock face itself.

VI

This act, in the decades surrounding the symphony’s composition, was only one of many similar events that transformed art into modern art. In drama it has common origins with the untempered shock dealt by August Strindberg’s chamber plays; it has affinities with Georges Braque’s and Pablo Picasso’s tableaux choses, with Isadora Duncan’s effort directly to objectify the inward, and with Wassily Kandinsky’s rejection of illusionistic space. The sculptor and dramatist Ernst Barlach formulated the Platonic antimimetic, antiart direction of modern art: “I do not represent what I for my part see, or how I see it from here or there, but what is, the real and the truthful. . . . The world is already there, it would be senseless just to repeat it.”9 Throughout these decades art moved fundamentally against fiction, against portraying or representing the world, and toward essence. Adorno shows in his major study of Schoenberg that he carried out this project in the medium of music, extending the illusion-shattering intention of Mahler’s hammer blows to the total musical structure. This was a radical transformation of musical expression. Whereas music since the seventeenth century had simulated subjectivity and dramatized passions, producing images of expression, Schoenberg’s break from tonality achieved a depositional expression, a docket of the historical unconscious that registered impulses of isolation, shock, and collapse.

This depositional capacity depended in the first place on the decline of tonality and the resulting possibility of a free manipulation of the musical material. But, second, for expression to be expression, it must be necessary; what occurs must have the quality of needing to be as it is. And what Schoenberg discovered—according to Adorno—was that the impulses sedimented in the material could be bindingly organized according to a principle of contrast. Dissonance, the bearer of historical suffering, would be the rational order binding together melody and harmony. Harmonic simultaneity would be that of independent contrasting voices. As a result, in Adorno’s words, “the subjective drive and the longing for self-proclamation without illusion, became the technical instrument of the objective work.”10 This transformed musical time: whereas the constitutive repetition of traditional forms makes music indifferent to time and susceptible to the background function required of popular music, in Schoenberg’s music the repetition of the Grundgestalt—the basic shape—must become new. It answers the dialectical question of how the old can become new at the same time that the music refuses to hold its even distance from the listener. Rather, in the words of Adorno’s Kafka description, it races toward the listener like a freight train. Schoenberg emancipated dissonance, but, more important, he made dissonance necessary.

Adorno’s understanding of the significance of this technique needs to be understood in the full context of Dialectic of Enlightenment, the companion text to, and written in part contemporaneously with, Philosophy of New Music. Whereas, extra-aesthetically, subjectivity translates phenomena into examples of a subordinating concept and thereby consumes the potential of expression, in Schoenberg’s music subjectivity organizes the nonidentity of the universal and the particular; it is an organization that, in its dissonance, constantly surpasses its own organization. The ideal that inheres in this music is a transformed subjectivity that, rather than dominating its object, gives it binding expression. Necessity in this case really is—for once—freedom in that inseparable from the bindingness of this music’s historical deposition is the sounding implication that what has transpired historically did not need to have happened and does not need to continue.