Boulevard Saint–Germain. Paris 6me. November. 4°C. Outside the café Les Deux Magots, a whiff of burning charcoal signifies that the chestnut seller is back at his old pitch, tending his improvised oil–drum stove. A dozen nuts smolder and crack on the ash–dusted metal. He shovels some into a white paper bag, around which a woman cups her palms: no hand warmer more effective, nor more fragrant.

I’D WATCHED THE SEASONS CHANGE ON FOUR CONTINENTS, BUT never as they did in Paris. As F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “Life starts all over again when it gets crisp in the fall.” Along the boulevards, one could sense the machinery meshing, cogs sliding into place as the engine of the year rotated into its final quarter.

The change can occur in a few seconds—as long as it takes a clock to strike the hour—and when one least expects it.

Crossing rue Bonaparte, beyond the tiny stall where a man cooks crepes to order on the hot plate—another winter smell: that of burnt sugar and Nutella chocolate–and–hazelnut paste—I spotted a further harbinger.

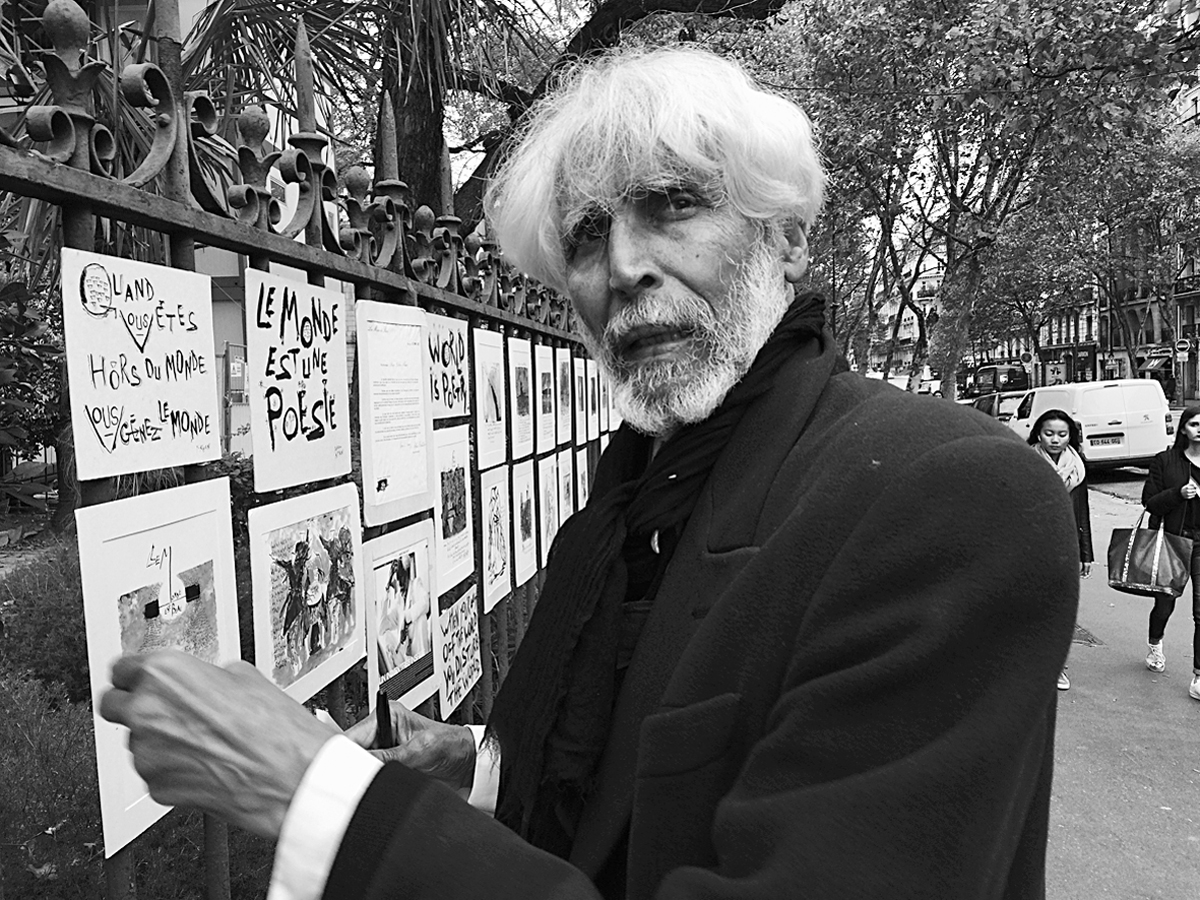

Yaseen Khan had once again hung his artwork from the railings of the little garden behind the church of Saint–Germain–des–Prés, each smudgy abstract surrounded by text in spiky calligraphy. He’s as much a fixture of this corner as the chestnut seller or the crepe man, and I seldom stop to look. But that day I did pause, because he’d chosen texts from a favorite poem, Jacques Prévert’s “Les Feuilles mortes” (the dead leaves).

To the corner of each stiff, parchmentlike paper was pinned a dead sycamore leaf. As much for the leaf as the poem I bought one, and, juggling it awkwardly as I fumbled for my ticket, only just managed to catch the 95 bus, direction Porte de Montmartre.

Squeezing into a seat, I adjusted my mental almanac to the passing of a season. The date could not have been more precise or final had it been printed on a calendar. Not savagely, like a wolf, as the Russians see it, but in the French style, silently, secretly, as a rime of ice gathers on still water in the night, winter was upon us.

Walking through the Jardins du Luxembourg an hour before, I’d seen the signs, just not recognized them. Instead, I was distracted by one of the twenty statues of France’s great women, larger than life, that surround the formal gardens of Marie de Médicis.

All but one of these statues depict queens or saints. The exception is the figure of a woman who, despite the cross around her neck and the wreath of laurel in her hair, stands in the seductive hipshot pose we associate more with showgirls. Flowers and more laurel leaves line her cloak, suggestive of someone not unacquainted with sensual pleasure. She is Clémence Isaure, the imaginary doyenne of Toulouse from whom Fabre d’Églantine claimed to have received his fictitious golden rose.

Yaseen Khan, artist of the Paris streets.

Photograph by the author.

Walking on, I didn’t notice that the tall date palms that had guarded Le Nôtre’s tranquil garden all summer were gone. Overnight, while the gates were shut (the time when everything of importance happens in the most discreet of Paris’s parks), forklifts conveyed the trees in their green–painted wooden crates to a graveled space behind the Musée du Luxembourg, creating a transient oasis through which I’d walked without taking notice. By now the trees would be installed inside the lofty hall of the Orangerie, safe from the frosts, which the evergreens that replaced them would just shrug off.

Then there were the leaves. Overnight, gardeners had corralled the fallen chestnut, plane, and sycamore leaves in the millions and heaped them in chicken–wire cages, each large enough to contain an automobile. Those that escaped made a carpet ankle–deep under the trees, or blew onto rue de Médicis to clog its gutters or plaster themselves to the sidewalks in a collage of beiges and browns.

London had just as many deciduous trees as Paris, but I didn’t remember seeing leaves in such abundance along the Mall or in Regent’s Park. Did their staffs do a better job of raking? I doubted it. Rather, those who maintained the Luxembourg chose to let leaves accumulate. Far from being a problem, they were part of the show.

At the end of my trip across the city, the bus deposited me in Montmartre. Busy, built up, high above Paris to the north, it’s a long way from the Luxembourg. As leaves don’t lie long in these windy streets, I wasn’t expecting to see any, which made what I found in La Souris Verte all the more surprising.

Away from the tourist trails, cafés cease to be a subject of curiosity for visitors and revert to an amenity for the French—somewhere to dawdle over a coffee, read the paper, do business, meet friends, watch le foot, and argue about last night’s result over a glass of Stella.

La Souris Verte (The Green Mouse) belongs in this category. The skylight over its high back room, the walls of unplastered brick, a bare–board floor unscrubbed since the de Gaulle administration, and some rugged stools and tables bolted together from balks of squared–off timber and looking suspiciously like recycled workbenches all suggest onetime industrial use—possibly as a sweatshop, a suspicion supported by a few tables adapted from old sewing–machine benches complete with foot treadles incorporating the Singer logo in wrought iron.

Autumn leaves on the floor of La Souris Verte.

Photograph by the author.

Some nights there’s a band, but mostly the sound system mumbles music chosen by whomever is behind the bar: thumping techno one day, the next some Belle Epoque art songs by Reynaldo Hahn or the mournful contralto of Nina Simone.

In the corner next to the bar, a stringless guitar and an ancient weighing machine with a broken glass emphasize that this is no branché boulevardier hangout. Hence my surprise that afternoon at finding its floor strewn with dead leaves.

Had they blown in? Unlikely. The door was closed, the sidewalk clear, with not a tree in sight.

I raised an eyebrow to the girl polishing glasses behind the bar. She shrugged.

“C’est pour le Beaujolais nouveau.”

The last cog meshed in the machinery of the changing season. Others more attuned to the seasons than I had seen the signs and, each in his own way, marked the occasion.

That morning, on rue des Écoles, a café owner had scattered straw across the entrance and placed a bale by the door. It was a reminder of the harvest, but there was also a notice from one of the big wine merchants stuck to his window announcing, “Le Beaujolais nouveau est arrivé” and urging us to sample it.

Nothing signified the shift from autumn to winter so visibly, at least for city people, as the arrival of the new Beaujolais on the third Thursday of November.

Strict rules govern what can be sold as Beaujolais nouveau. Only wine from the regions of Beaujolais and Beaujolais–Villages may use the term, and then only if the wine is pressed from Gamay grapes and matured by a process that produces fermentation in a mere twenty–one days.

For a little wine, Beaujolais nouveau became big business. At one time, restaurateurs all over the world competed to be the first to offer the new vintage. Runners, rickshaws, trucks, helicopters, hot–air balloons, motorcycles, Concorde jets, even elephants were employed to rush a case from the vineyards north of Lyon in time for customers to open a bottle at one minute past midnight on that third Thursday.

Today, the onetime rarity has become a cliché. Sixty–five million bottles are sold worldwide every year, mostly to people who can’t tell Cabernet from Kool–Aid. One critic dismissed the wine in its present state as “nothing more than pleasantly tart barroom swill.”

But to write it off is to miss the point. If the Beaujolais nouveau had value, it lay in the idea behind it. Like the Romans who ceremonially spilled wine on the ground as an offering to the gods, we drank it as a libation, a sacrifice to the inevitability of change.

Ahead lay hard months from which it would not be so easy to wring a wine as pleasant as this. But winter had its pleasures too. Long before I came here, I read Paul Bowles’s evocation of “the hushed, intense cold that lay over the Seine in the early morning, the lavender–gray daylight that filtered down from the damp sky at noon; even on clear days the useless, impossibly distant, small sun.” I was ready. Yaseen Khan and the chestnut seller and La Souris Verte and Beaujolais nouveau had prepared the way. And Fabre d’Églantine too, in his fashion. Send on Frimaire, Nivôse, and Pluviôse, and the days of granite, salt, and iron. We would deal with them together.