Malibu, California. August 1988. 2 a.m. 14°C. A chattering crowd fringes the beach as waves of the silver fish called grunion slither ashore, carpeting the zone where water meets sand. As females lay their eggs in the tidal flow, males ejaculate spasmodically into the soup of saltwater, sand, and milt before the ebb carries them, spent, back out to sea. Gleefully, watchers scoop them up in buckets, ingredients for a late supper.

PEOPLE OFTEN ASK, “WHAT’S THE BEST TIME TO COME TO PARIS?”

Before I moved here, I would have said, “Well, I suppose April,” not from conviction but simply because the song “April in Paris” is so ubiquitous that it could be the city’s theme. From Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra to the entire Count Basie band—discovered, in Mel Brooks’s comedy western Blazing Saddles, blasting it out in the midst of the Arizona desert—it has more than earned its status as a standard. Composer Alec Wilder insists, “This is a perfect theater song. If that sounds too reverent, then I’ll reduce the praise to ‘perfectly wonderful,’ or else say that if it’s not perfect, show me why it isn’t.”

A jazz listener since adolescence, I’d grown up with “April in Paris,” but like most things encountered early in life, since taken it for granted.

It comes from an obscure 1932 Broadway show, Walk a Little Faster. The composer was Vladimir Dukelsky, who chose to work as Vernon Duke.

The lyrics were by E. Y. “Yip” Harburg, who wrote “Over the Rainbow” but also “Lydia the Tattooed Lady,” with its catalog of body art made memorable by Groucho Marx: “Here’s Captain Spaulding exploring the Amazon / Here’s Godiva but with her pajamas on,” not to mention “Here’s Nijinsky, doing the rumba. / Here’s her social security numba.”

“April in Paris” didn’t aspire to that degree of invention. Its first few lines—“April in Paris, chestnuts in blossom / Holiday tables under the trees”—produced no frisson of recognition. They didn’t even rival another Duke/Harburg collaboration, “Autumn in New York,” with its sly couplet “Lovers that bless the dark / On benches in Central Park.”

To my surprise, “April in Paris” has an introductory verse, but it’s seldom performed. Reading the lyrics, claiming that April brought a “tang of wine in the air,” I wasn’t surprised.

Wondering if I was missing some nuance, I ran the lyrics past my gastronome friend Boris. Able to spot the bogus at a hundred meters, he didn’t disappoint.

“‘The tang of wine’? Who wrote this? Had he ever even been to Paris?”

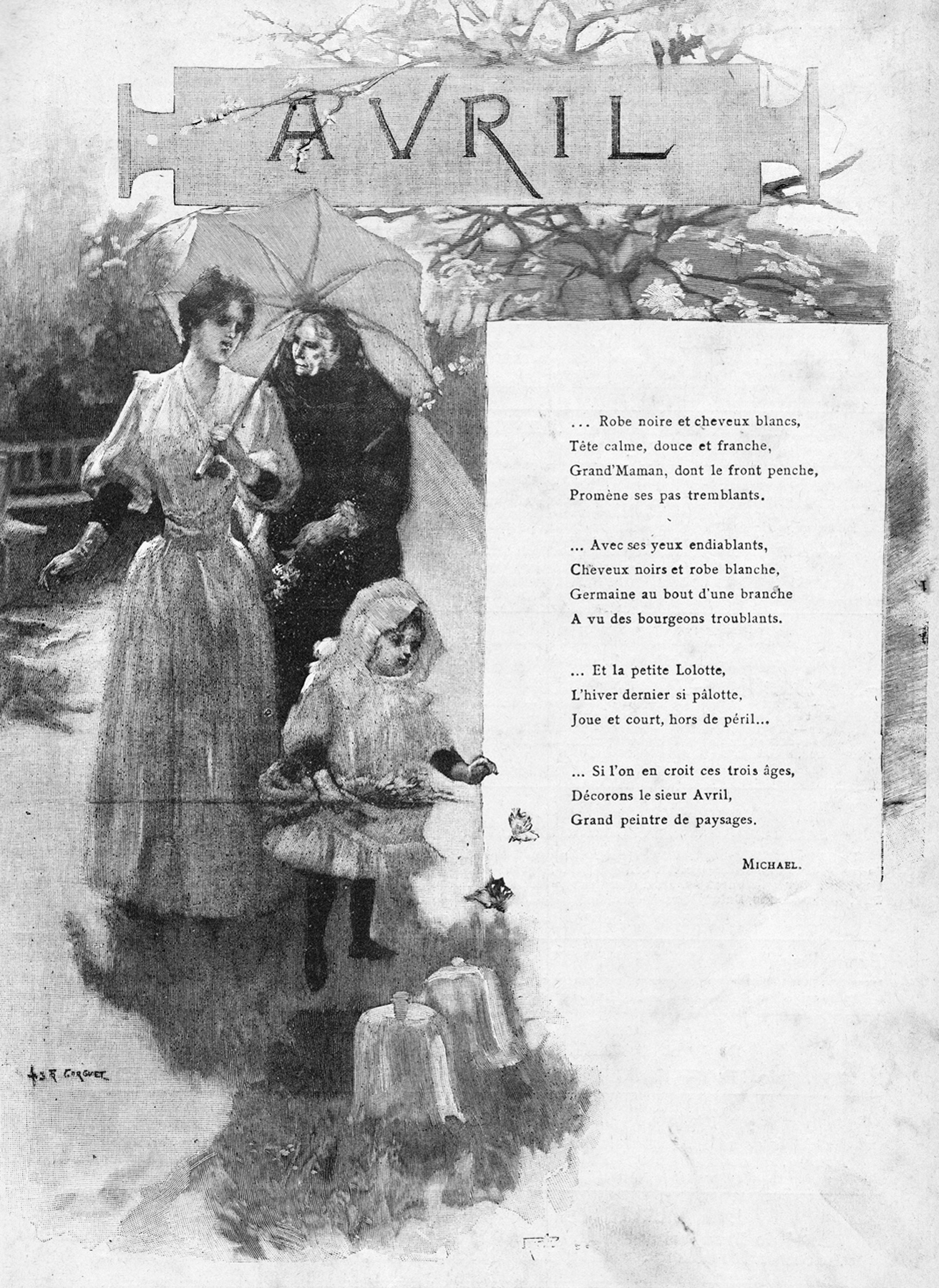

A melancholy vision of April in Paris.

Gorguet, Auguste François. A Melancholy Vision of April. April 1892. Wikimedia Commons.

“In fact, Duke lived here for years,” I said. “He wrote a ballet for Diaghilev, was a friend of Prokofiev. But Harburg . . . I doubt it.”

I didn’t mention Lydia and her tattoos. Why call down more scorn on my head?

“And ‘chestnuts in blossom, holiday tables under the trees’? Those are hardly unique to April.”

He was right. The marron (chestnut), Paris’s most common tree, flowered throughout the spring. And as for “holiday tables under the trees,” April has no monopoly on those. A blizzard needs to be blowing before café owners take in the highly profitable tables and chairs ranged along the sidewalk. Some hand out blankets for clients to wrap around their legs and keep right on serving even when the unprotected parts of their patrons begin to turn blue.

By 1952, the fantasy of April in Paris was comprehensively blown. The writers of April in Paris, a film released that year starring Doris Day, seemed actually to know the city, since they poked fun at the whole idea. Day, a new arrival in France and eager to experience its widely advertised warmth, gaiety, and romance, convinces her leading man to sit outside at a café, even when a waiter, teeth chattering, urges them to move inside. When Day refuses, he takes cover himself, telling them he’ll be back in July.

A journalist friend had other reasons for disliking “April in Paris.”

“I can’t tell you how tired I am of that song,” he said. “Every year, they dust it off on the first day of April. On TV they play it over a montage of cafés and flowers, all from last summer, of course. It’s a marron, a chestnut.” He had a sudden thought. “You know, don’t you, that’s why anything boring—an old joke, or this TV thing—is called a ‘chestnut’? There used to be an old marron tree in the Tuileries that was the first to flower every spring. In England you have the first call of the cuckoo bird, and in America that rat thing—”

“A groundhog, actually,” I said. “Name’s Punxsutawney Phil.”

“C’est vrai? Merde alors!” He raised his eyebrows, partly at the name but mostly at the fact that I should know about it.

“Well, in Paris,” he went on, “the first sign of spring was this marron flowering. So some reporter was sent to write a piece about it. Usually it was the stagiaire.” Obviously he had once been such a trainee himself. “A horrible job. What can one say that hasn’t been said a thousand times before? C’est ennuyeux. So that’s why we say that anything like that is a marron, a chestnut.”

Worse and worse. The credibility of April in Paris as the inspiration for a song was evaporating before my eyes. So why would Duke write something that so poorly described a city he must have known intimately? Could it be no more than the fact that “April in Paris” fell more agreeably on the ear than “March,” “May,” “June,” or “July in Paris”?

As I discovered after more research, it may all have been the fault of writer Dorothy Parker, a friend of lyricist Harburg. A cynic’s cynic and a mistress of acid wordplay—“If all the women [at this party] were laid end to end, I wouldn’t be at all surprised”—Parker was a poet of the glass–half–empty persuasion. Life to her was one long disappointment, its pain assuaged by liberal applications of gin and sex.

According to one account, Parker was within earshot when Vernon Duke referred to Robert Browning’s poem “Home–Thoughts, from Abroad” as a possible theme for a song. Was there a tune to be had from this dithyramb to the English spring, with its famous first lines “Oh, to be in England / Now that April’s there”?

Through her tenth martini, darkly, Parker saw nothing appealing about England in April. The fogs, the rain, and, my dear, the people!

But France . . . Now that was something else.

“Oh, to be in Paris,” she murmured, “now that April’s there.”

And from this bitter soil a song germinated? Isn’t it pretty to think so.