Near Épernay, region of the Marne. June 18, 1944. The supreme allied commander notices that the sector of the advance controlled by the French is lagging behind the others. An intelligence officer is sent to discover the reason. He finds the entire French high command in a tent, bent over a copy of the Atlas des vins de France. They are planning a route that will take them past every great vineyard in Champagne.

HOW COULD ANYONE HAVE SERIOUSLY BELIEVED THAT FRENCH farmers would understand the Republican calendar, let alone embrace it? All had been brought up within the sound of church bells. Married in the church, they named and raised their children in the church and were buried by the church. Its influence was not to be expunged with the stroke of a pen.

Had the calendar commission included a farmer, merchant, or tradesman, they would have seen immediately that their creation rested on an illusion. Farmers knew from experience the importance of seasons and the weather. The biblical injunction to respect “a time to sow and a time to reap” left dates and times to be interpreted according to a sense of the seasons that needed no calendar except the one the farmer wrote for himself.

Given time, wiser heads within the Convention would have allowed the scheme to languish. But the circumstances that created it also blinded the creators to its faults. For a nation that could in a few years go from a monarchy to a republic by the most direct route, that of exterminating its ruling class, anything was possible. Some of the revolution’s innovations enjoyed surprising success. The metric system would soon be in use across Europe. And the guillotine, only introduced in 1792, became almost overnight an unignorable feature of French political life.

Over the next few years, some parts of the new calendar were enacted, others ignored. At the same time, people were put to work publicizing its merits. One man would do more than anyone to bring Fabre’s creation to life, however briefly.

Louis Lafitte was twenty years younger than Fabre. The two never met. Yet Lafitte would put faces to what were just names in the original calendar, and in doing so, humanize it for an international audience.

In 1791, as a young artist at the end of a punishing four–year course at the École des Beaux–Arts, Lafitte won the prestigious Prix de Rome, entitling him to a year of study, all expenses paid, in the Italian capital. In Rome, he worked at the Villa Medici until deteriorating relations between France and Italy made life uncomfortable for Frenchmen there. In 1793 he moved to Florence, where he waited out the Terror as a teacher before returning to France.

Lafitte won his Prix de Rome with a classic history painting of an incident from the Punic Wars, a canvas crowded with heroic figures, meticulously painted drapery, and painstakingly depicted architecture, a style hopelessly unfashionable in a new and aggressively working–class France. With a wife and daughter to support, Lafitte took work where he could find it, painting murals, decorating private homes, and illustrating books. (There was a special frisson for me to discover that he had lived and worked on rue de l’Odéon, just a few doors away from our home.)

His fortunes changed in 1796, when a publisher issuing a new edition of the Republican calendar commissioned twelve paintings to illustrate the months.

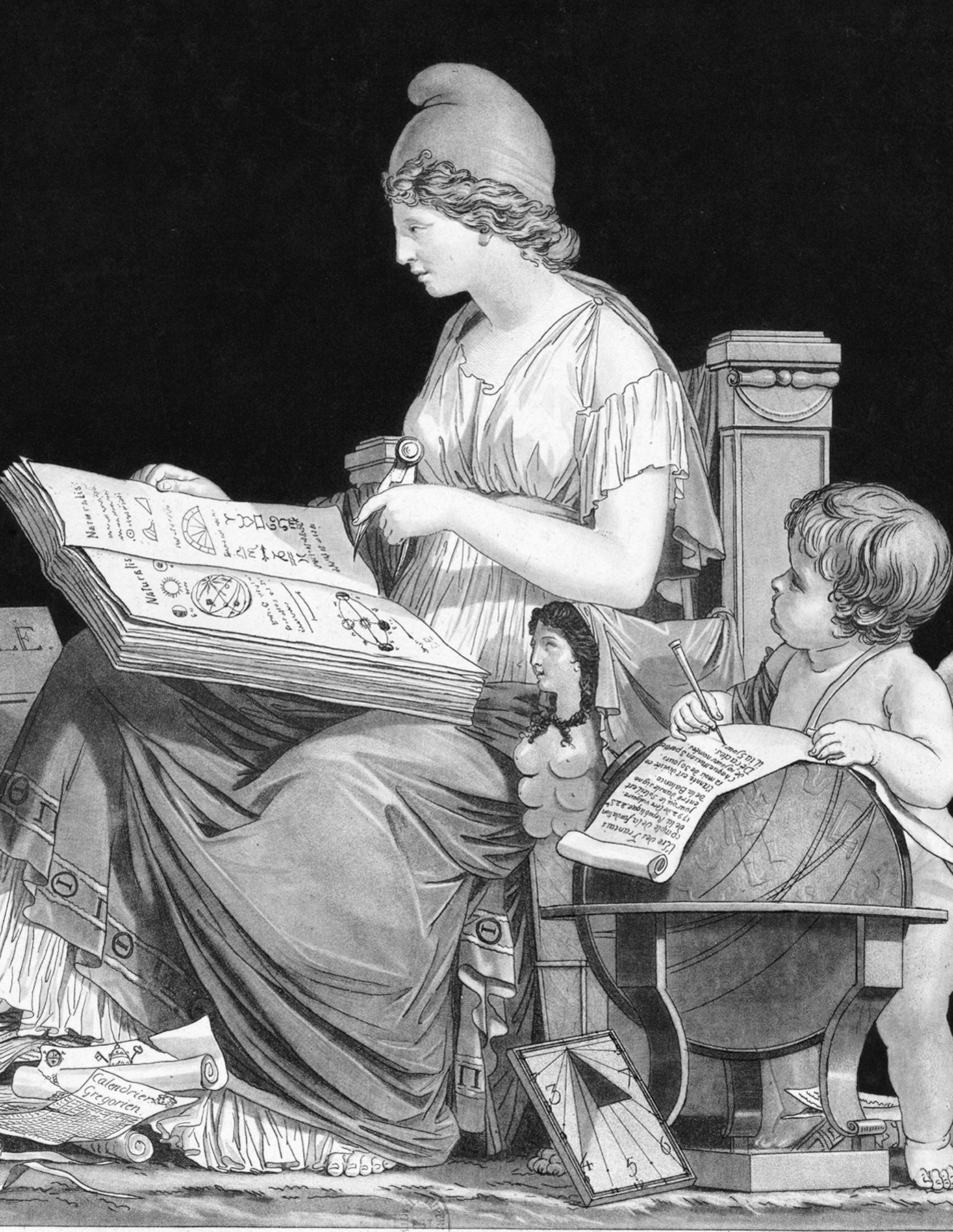

Until the revolution, only religious illustrations had been permitted in almanacs and calendars. Even after 1789, editions of the calendar favored the politically respectable. For a 1794 printing, Philibert–Louis Debucourt provided an austere neoclassical illustration showing Marianne, the spirit of the revolution, paging through the Book of Nature as a cherub takes notes. In the frontispiece for another edition, Marianne descends the steps of a temple at the foot of which lie the corpses of other calendar makers, clutching their discredited creations.

Perhaps seeing an opportunity to re–establish himself on the Paris art scene, Lafitte took a radically different line. From a memory filled with voluptuous images from Italy, he created something entirely new: a panorama of the French countryside and its female inhabitants as no person in the street, let alone any farmer, had ever seen them.

The new Republic rewrites the calendar.

Debucourt, Philibert–Louise. The New Republic Rewrites the Calendar. Author’s collection.

Each of his paintings featured an attractive young woman, lightly dressed, posed with an animal, plant, flower, or implement chosen from those listed by Fabre. A brief poem under each illustration underlined its significance, generally with a double entendre.

Lafitte’s images were bold. Doves cuddle up to the dark–haired beauty of Germinal, spreading their wings across her breasts. The pensive brunette representing Prairial fingers two more of these birds nestling on her pubic area.

Thermidor, the month of heat, is accorded the most frank image of all. In an unsubtle evocation of the legend of Leda, ravished by Zeus disguised as a swan, it shows such a bird, one webbed foot planted in the woman’s crotch, extending its sinuously phallic neck at full length over the young woman’s naked breasts. To one side, a watching satyr, part of a bronze cup, appears to be engaged in some uncomfortable act of self–abuse.

After having the images engraved on copper by Salvatore Tresca and the reproductions colored by hand, the publisher, scenting a bestseller, printed a second deluxe version “for art lovers and connoisseurs.” Printed on transparent oiled paper, it allowed Lafitte’s images to be displayed backlit in the style of a stained–glass window.

In effect, Lafitte had created the first pinup calendar. His work foreshadowed countless peekaboo beauties in skimpy clothing, or none at all, who would decorate locker rooms and workshops for the next two hundred years.

Thermidor. Leda and the swan, reinterpreted by Louis Lafitte.

Lafitte, Louis. Thermidor. Author’s collection.