Paris 16me. August 1976. 26°C. Dust as fine as talcum sifts through shutters closed against the sun. It films the black lacquer of the Bechstein grand, makes even more slick the waxed wooden blocks of the parquet floor, coats the cream–and–green enamel of the kitchen’s antique refrigerator and stove, grits between the teeth in the aftermath of a kiss.

I FIRST HEARD OF THE REPUBLICAN CALENDAR IN THE 1970S, WHEN I lived in London. The year is irrelevant, but men were wearing their hair long, women theirs short. Flowered shirts and beads were the rage, and everyone seemed to be playing Elton John’s “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me.”

Céline and I hooked up at a party in Chelsea, London’s equivalent of Greenwich Village, Trastevere, Montparnasse. The hostess was her daughter, Kissy, a bosomy twentysomething with pretensions to art. But her real talent lay in having her cake and eating it, a skill she’d exploited to score a show at one of the pop–up galleries that sprouted around East London like mushrooms after rain and expired just as speedily.

Her apartment showed more flair than her canvases. In a style best described as “Moorish whorehouse,” she’d draped filmy fabric from the ceilings, turning every room into a tent under which incense blended with cannabis smoke in an exotic miasma.

Céline, slim and pale with short dark hair, belonged to that segment of women diplomatically described by the French as femmes d’un certain âge. Her black silk trouser suit sometimes masked the shape of her body, at other times clung to it, evidence for the suggestion that silk was invented in order that women could go naked while still clothed. What won me, however, was her voice. If French is the language of diplomacy, English spoken with a French accent must be the language of seduction.

A friend once confided to me a preference for “older women with a Past.” I responded with a line spoken by Brigitte Auber in Alfred Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief, in which she plays a hot young Frenchwoman. Mocking Cary Grant’s preference for Grace Kelly over her, she asks, “Why buy an old car if you can get a new one cheaper? It will run better and last longer.”

If I had ever harbored such prejudices against age, Céline demolished them. So this was why Charles Swann in Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time) could moan of his attraction to Odette de Crécy, “To think that I wasted years of my life, that I wanted to die, that I felt my deepest love, for a woman who did not appeal to me, who was not my type!”

Some relationships fly in air so thin that any conventional attraction would fall of its own weight. Ours justified the use of words like “enchantment.” After the party, we walked back in silence through the empty streets and climbed the six floors to my apartment.

“So bare,” she said, looking around my living room. “No pictures?”

Bare? I’d aimed for minimalist.

She strolled into the bedroom and shrugged off her jacket. A slither of silk.

“You do not like a big bed?”

Queen–size had always seemed large enough, but now I wondered.

She began to undress. Lingerie to die for. Coffee silk, with lace along the hems.

“You have candles? No?”

She draped her scarf over the lamp. What I’d taken for black was deep purple. Shadows took on the soft bloom of a bruise.

Our affair ignited that night. Once she went home, I slipped across to Paris every few weeks to spend a weekend in her sprawling apartment in the seizième.

Kissy kept a room there but never visited, at least not when I was around, and though a femme de ménage came twice a week to clean, all I ever saw of her was a fresh wax shine on the parquet and new linen on the bed. Woven so densely it felt heavy, as though soaked in water, each sheet was embroidered with an incomprehensible monogram, signifying Céline’s marriage to a husband even less evident than Kissy, barely more than a phantom presence somewhere on the far side of the world.

Years later, I saw my experience with Céline mirrored in Le Divorce, a novel by the American writer Diane Johnson. Her main character is an American woman who takes a much older Frenchman as a lover. Reveling in the way he instructs her in the intricacies of life in Paris, she muses, “If you didn’t know where to look, you could pass your whole life with no sense of what you were missing.” As far as France was concerned, Céline was as much teacher as lover.

That was when I first heard of Philippe–François–Nazaire Fabre d’Églantine—“Fabre of the Wild Rose”—and his plan to redesign the year, cutting and shaping the seasons as a couturier tailors a gown to show off the best points of his client.

It was August, a month that descends on Paris like a curse. Empty streets echo with the clatter of jackhammers as café owners rush through renovations before their clientele floods back in early September. By noon it was too hot to move, to eat, certainly to make love, so we read and dozed, pressing to our foreheads the glasses of homemade limeade, beaded with moisture, that we drank by the liter.

In another room a radio was tuned almost inaudibly to a jazz station. After a few bars of one tune, Céline opened her violet eyes and murmured a few words:

“Balayé par septembre, notre amour d’un été . . .”

They meant nothing to me, but I thought I recognized the singer’s husky baritone.

“Is that Aznavour?”

“Yes. ‘Paris au mois d’août.’ ‘Paris in the Month of August.’”

At the time, I caught only the sense of the song. Later I looked up the words, and their translation.

Swept away by September

Our summertime love

Sadly comes apart

And dies, in the past tense.

Even though I expected it,

My heart empties itself of everything.

It could even be mistaken

For Paris in the month of August.

The words caught the lassitude of what the French call le canicule, so much more evocative than our “heat wave.” Canicule because these are the “dog days,” when Sirius, the Dog Star, is in the ascendant. The languorous despair evoked by the song was almost pleasurable. As Noël Coward said, “Extraordinary how potent cheap music is.”

“Comme il est triste,” Céline sighed as she listened. “Just right for Thermidor.”

“Thermidor?” I said. “Like lobster thermidor?”

She punched my arm, but playfully. “No! Not like the lobster—or not only like the lobster, at least. Why is it always food with you? Or films.”

“Tell me, then.”

She let her book fall and leaned back on the cushions of the couch.

“Very well. But first you must kiss me.”

Breathlessly, I obeyed her.

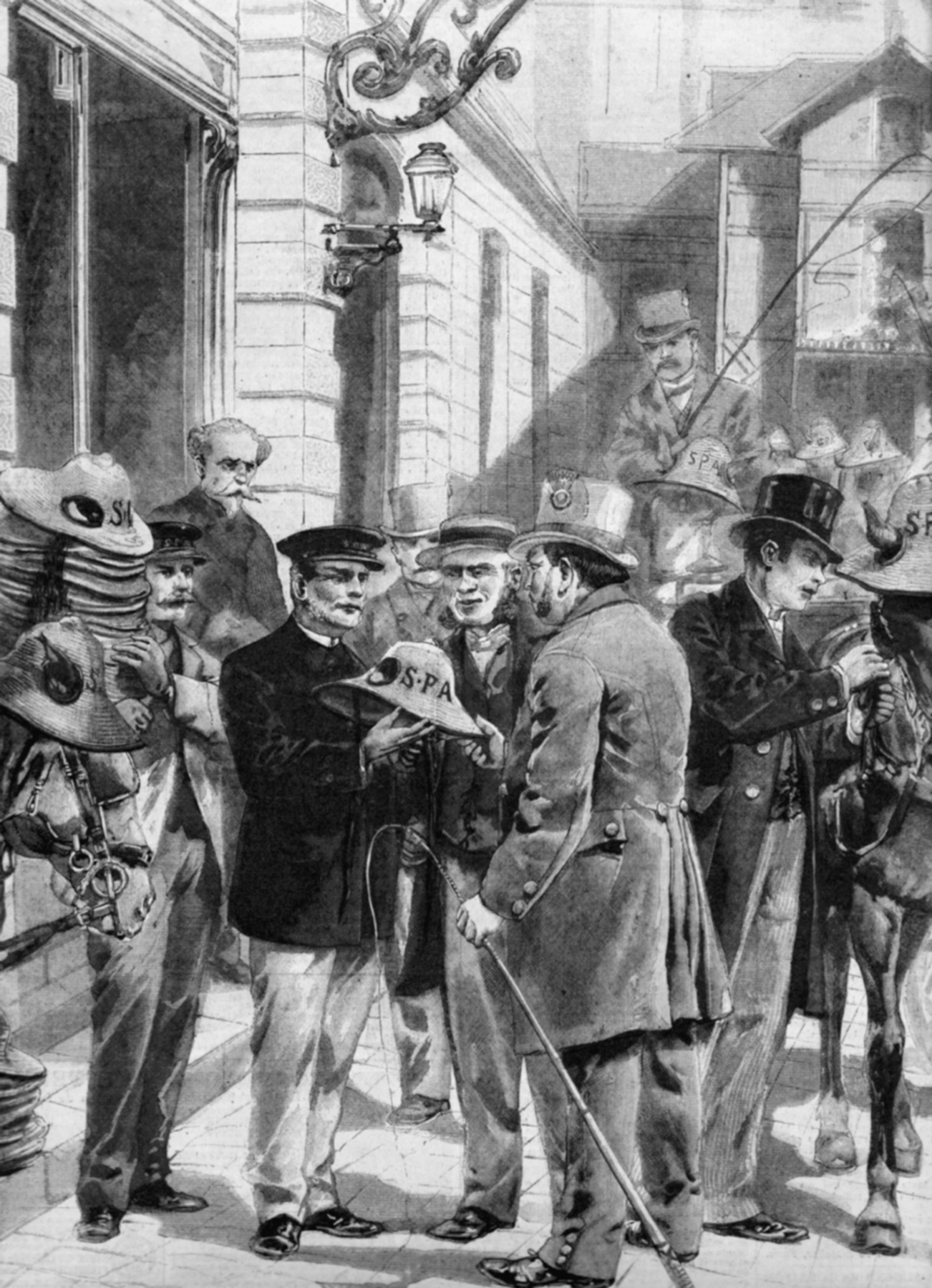

Distributing hats for horses during a Paris heat wave, 1890s.

Unknown. La Chaleur de Paris. Chapeaux pour chevaux. In Le Petit Parisien.