Balmain, Sydney. December 1998. 40°C. As I sit and read, Marie–Dominique swims laps on a rooftop pool. Louise, age eight, matches her stroke for stroke, dipping below her, surfacing ahead, effortless as a seal—being comfortable in her body, an attribute I lacked, was conferred on her at birth.

FOR CENTURIES, THE CITY OF PARIS HAS TRIED TO MAKE SUMMER more bearable for those stranded there. In the 1990s, it spread tons of sand along a stretch of the stone–paved bank of the Seine next to the Pont Neuf. On this Paris plage (Paris beach) you could sunbathe, flirt, make sandcastles, dance, drink sodas, eat ice cream—just not swim, since nobody in their right mind would risk going into water described as far back as 1844 as “sale, troublé, souvent fétide et malsaine” (dirty, turbid, often foul smelling, and unhealthy.)

Despite this, there were always a few people determined to swim. For them, generations of entrepreneurs have built public pools, or piscines. Often little more than half–sunken barges, they offered river water from which at least the larger pieces of debris and most dead animals had been removed. Better filtering had to wait until the mid–1930s, and it only became standard during the Nazi occupation, when German officers, for whom the pools were reserved, demanded it.

Paris’s first piscines appeared late in the eighteenth century. At one time the Seine supported twenty, of which Piscine Deligny, next to the Place de la Concorde, was the most fashionable. Opened in 1785, it belonged to Barthélémy Turquin, who’s also credited with inventing the life jacket. In 1801, his son–in–law took over. A skilled self–promoter who styled himself “Maître–nageur Deligny” (master swimmer Deligny), he attached his surname to the until–then–anonymous pool.

In 1840 the Burghs, two enterprising brothers, rebuilt Piscine Deligny. They used timber from the Dorade, the steamboat that carried Napoléon’s body up the Seine for reburial when it was returned from Saint Helena to Paris that year. Appropriate to such a patron, they surrounded the pool with oriental–style terraces and cafés to create a cigar divan, or Turkish café.

During the Belle Epoque, men–about–town strolled there in the afternoon to smoke and take coffee, but mostly to admire the women in their clinging wool maillots de bain. Marcel Proust’s mother was among them. He remembered her “splashing and laughing there, blowing him kisses and climbing again ashore, looking so lovely in her dripping rubber helmet, he would not have felt surprised had he been told that he was the son of a goddess.”

The Deligny offered private cabins, technically for changing clothes but often misused. One habitué reminisced, “American girls learning French at the Alliance Française, just three Metro stops away, would come down to the pool. They seemed to enjoy perfecting their French with me. Sometimes I would take the girls into my cabin to continue their French lessons. It was charming, if not altogether comfortable.”

Piscine Deligny, 1954.

Anonymous. Piscine Deligny. June 1954. Author’s collection.

By the 1980s the Deligny was showing its age, and the clientele, in line with venues like the Astoria Baths in New York City, had become almost entirely gay. Its borrowed time ran out in August 1993 when, ignominiously and mysteriously, the ancient construction broke up one night, its rotted timbers settling to the mud of the Seine in what was probably the first example of a swimming pool destroyed by sinking.

A new generation of pools had already supplanted the old wooden establishments. Its star was Piscine Molitor, a landlocked complex that opened in 1929. Olympic champion Johnny Weissmuller hosted the premiere, trained there, and acted as honorary lifeguard until Hollywood recruited him to play Tarzan.

To Parisians, few of whom even had bathrooms, Piscine Molitor offered a taste of luxury. Designed in art deco style, it echoed the liners then plowing the Atlantic. Inside, it was easy to believe one was on the high seas. The city disappeared behind walls of changing cabins topped by cafés, sports shops, hairdressers, and an esplanade that supplanted the terrace of the Deligny as a pickup spot.

In winter a retractable roof covered the space, and the water was frozen for ice skating. At other times it hosted fashion shows and beauty contests. In 1946, swimwear designer Louis Réard chose it to unveil the abbreviated two–piece swimsuit he named the “Bikini,” after the Pacific atoll where atomic weapons were tested. When every reputable mannequin refused to model the outfit—small enough, Réard boasted, to fit in a matchbox—he hired showgirl Micheline Bernardini, wife of entrepreneur Alain Bernardin, who would, shortly after, launch what became the city’s most famous erotic cabaret, the Crazy Horse Saloon.

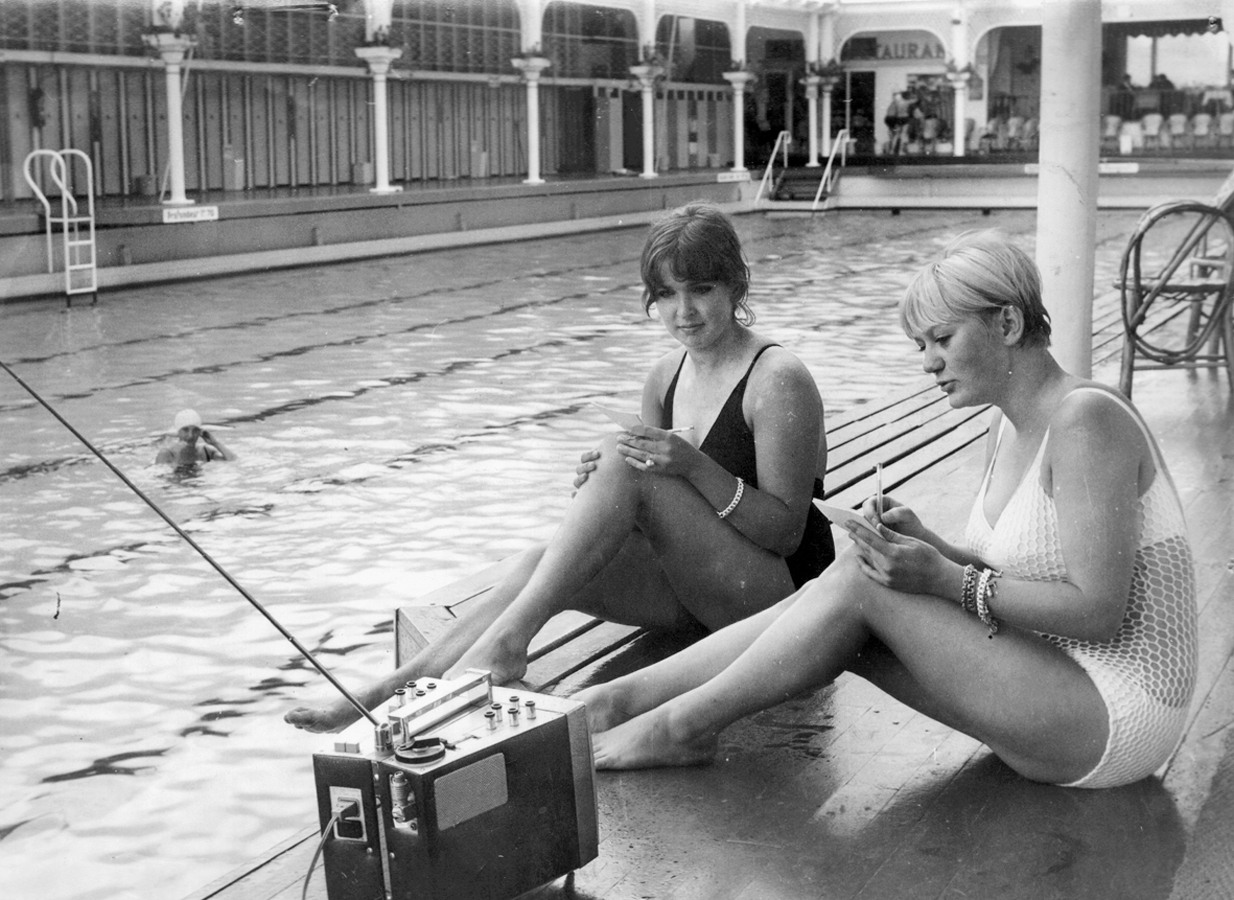

Homework at Piscine Molitor, 1966.

Anonymous. Homework at Piscine Molitor. August 1966. Agence France–Presse.

After years in decline, the Molitor was modernized in the early twenty–first century. It was incorporated into a hotel complex sufficiently chic to provide a location for the film Life of Pi, although critics complained that doors that once opened onto invitingly intimate changing rooms now hid only blank concrete.

A few other public pools survive, including a floating creation in fiberglass in the thirteenth arrondissement, named, improbably, for dancer/singer Josephine Baker. Not notably aquatic, she may never even have set foot in such an unfashionable district, far from the clubs and cabarets of Montmartre.

The city has persevered in trying to create a more permanent and accessible space for swimming. In 2016 it dredged a stretch of the Canal Saint–Martin, along which barges used to haul goods into the city. Some hundreds of rusty bicycles later, plus a few handguns and copious quantities of drug paraphernalia, this improvised lido opened—only to close almost immediately.

Micheline Bernardini and the first bikini, small enough to fit in a matchbox.

Anonymous. Micheline Bernardini at Piscine Molitor. July 5, 1946. Author’s collection.

Oliver Gee, an Australian journalist friend, covered the cleanup. I asked him if he knew why the project failed.

“Well, I have an idea . . .”

It took some time to coax out the story, but it was worth the effort.

Following up on a rumor that hinted the canal harbored some living inhabitants—specifically, a large beaver—Oliver approached an elderly lady sitting by the water and asked if she’d ever seen such a beast.

“Un castor?” She shook her head. “No, not a castor . . .”

“Are you suggesting some other animal?” he prompted.

(As he told me later, “I thought, you know, maybe rats. Even an otter. But not what came next.”)

“The only animals I’m certain lived here,” she continued, “are crocodiles.”

“Crocodiles?” Oliver said, startled. “How would crocodiles get into the Canal Saint–Martin?”

She lowered her eyes in embarrassment. “I put them there.”

Hearing this, I couldn’t help being skeptical. In New York, perhaps, but Paris?

The existence of alligators and crocodiles under Manhattan was an urban myth of the 1980s. People who’d bought such animals as pets were alarmed when they became large enough to cast thoughtful glances at the family Chihuahua, if not the children. They dumped them down the nearest toilet or storm drain, from where they reached the sewers and thrived.

Oliver had been just as skeptical. With commendable journalistic zeal, he pursued the story, pressing the lady on where she got the animals (from sanitation workers, she claimed, who found them under her house in the Marais, Paris’s oldest district) and why she dumped them in the canal (they were getting too big and aggressive to be kept as pets.)

“So . . . did you believe her?” I asked.

“Well, yes,” Oliver said. “Eventually. Because it’s happened before. Have you heard of Eleanore, the crocodile of the Pont Neuf?”

I hadn’t, but an internet search brought me up to date. In March 1984, workers cleaning drains near the Pont Neuf, Paris’s oldest bridge, alerted the fire service to the presence of a small crocodile in the sewer.

“She measured between two and three feet,” said one of the sapeurs–pompiers who trapped her. “We used a shovel and brooms to hold her down, then we tied her around the nose to stop her biting.”

A marine biologist identified her as a female Crocodylus niloticus, or Nile crocodile, and none the worse for her ordeal.

“Is it likely,” I asked Marie–Dominique after I found this article, “that a crocodile could live in the Seine near the Pont Neuf?”

“Well, if any animal could, it’d be a crocodile. And,” she added thoughtfully, “it is right next to the Quai de la Mégisserie.”

The pet shops that line that stretch of boulevard running above the river have long been suspected of consigning unsalable animals to the Seine. If it could swallow puppies and kittens that had outgrown their cuteness, why not a crocodile?

The story even has a happy ending. Having been in the papers, the escapee of 1984 became a celebrity and could not be allowed to disappear. At Vannes, along the Atlantic coast of Brittany, an aquarium adopted her and christened her Eleanore.

Today, ten feet long and weighing more than five hundred pounds, she luxuriates in her own ocean–side condo. It replicates in gray cement the corner of les égouts where she was captured, complete with a traditional blue enamel plaque identifying her address as Pont Neuf. Elements of a sewer worker’s outfit hang on the wall, though visitors willing to put on the helmet and boots to pay her a visit are few and far between. This suits Eleanore. Like most stars, she values her privacy.

Now, crossing the Pont Neuf, I occasionally pause and look down into the roiling water, alert for the glint of a saurian eye, the flick of a scaly tail. If I needed another excuse not to swim in the Seine, memories of Eleanore would serve very well.