34

Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris. June 6, 1911. 10 p.m. 28°C. Vaslav Nijinsky dances the Paris premiere of Le Spectre de la rose, concluding with his heart-stopping leap through an open window. On the other side, four young members of the city’s gay elite, among them Jean Cocteau, wait to catch him in midair. Wrapped in warm towels, he’s carried, exhausted, to a bath filled with warm water, where they peel off his skintight costume and sponge the sweat from his shivering naked body.

IT MAY BE ONLY IN FRANCE THAT THE ARRIVAL OF SPRING FAILS TO excite the most exuberant emotions.

Italian music soars in praise of warmth’s return and the reaffirmation of life, and Russian novels ring with ecstatic evocations of that moment when the rivers thaw and begin again to flow. In Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Andrei Bolkonsky sees his ruined life symbolized in an apparently dead oak. Passing again in spring, he finds the tree in vigorous full leaf and is seized by “a causeless springtime feeling of joy and renewal.”

Anyone who studies English literature beyond fifth grade will eventually encounter William Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and its celebration of April, which “with its sweet-smelling shower has pierced the drought of March to the root.”

Even American students unfamiliar with fourteenth-century English verse welcome April as the month of spring break, and the start of the season of wet T-shirts and beer pong.

Not so France. To the French, March and April are too early to celebrate a year that’s hardly begun. These are the months to get one’s head down, to work long hours and concentrate on the golden days of July and August, the vacances, when one can mellow back and truly appreciate the sensual possibilities of the greatest country in the world.

Fabre d’Églantine seems to have sensed this in his bones. Why else would he have chosen poisonous hemlock, a knife, and the Judas tree to signify Germinal, the month that began on the former March 21 and ran to April 19? They imply apprehension, distaste, and a recognition that so fundamental a disturbance in nature must have a price.

One could almost believe that Fabre was present in spirit at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on the night of May 29, 1913, for the premiere of a new ballet by the Ballets Russes of Sergei Diaghilev, Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring), to music by Igor Stravinsky. It would have been day 10 of Prairial in the new calendar, and the emblematic object, appropriately, was the faux, or “scythe.”

The Paris appearances of the Ballets Russes reflected the respect for seasons that dominated French theater, art, and fashion. Diaghilev developed ballets to a peak of refinement, then unveiled them in seasons of three or four productions. After playing them in repertory in Paris for a few weeks, they moved on to Rome or London, riding, it was hoped, a wave of exuberant reviews and leaving behind an audience more eager than ever for the company’s return.

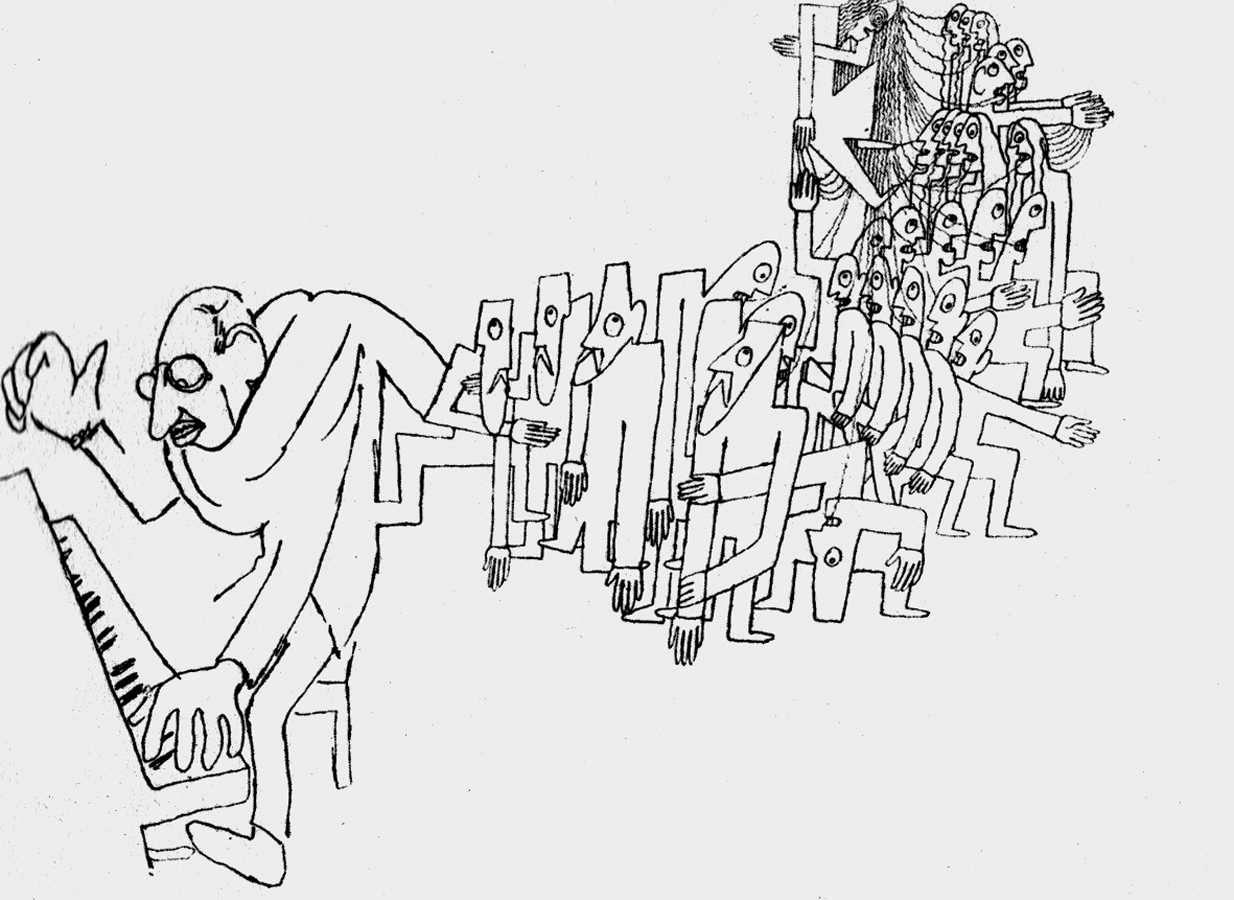

Jean Cocteau’s impression of Igor Stravinsky composing The Rite of Spring.

Aware of the shock effect of his ballets, Diaghilev strove to maximize it. When Jean Cocteau asked what it would take to have him commission a ballet, the impresario simply said, “Astonish me.”

As he readied the 1913 season, Paris was still digesting the stylistic advances of 1909, when the gorgeous costumes and decor of Léon Bakst and Alexandre Benois, the music of Borodin and Rimsky-Korsakov, and, above all, the dancing and choreography of Vaslav Nijinsky had ripped through the artistic community in a shrapnel of new ideas that transformed fashion, music, and design.

The year 1910 brought a startling version of Debussy’s L’Après-midi d’un faune, for which Nijinsky both conceived the choreography and danced the role of a satyr, half man, half goat. Mirroring the two-dimensional decorations on Greek vases, he acted out an erotic encounter with some nymphs, at the climax of which he lay facedown on a scarf one had left behind and masturbated.

Nijinsky again dominated the 1911 season with Le Spectre de la rose. A dreaming girl conjures up her vision of erotic desire, the embodiment of a rose. When she has been excited to the peak of ecstasy, the spirit launches itself weightlessly through a window, apparently to disperse on the evening air.

For 1913, Diaghilev needed something even more innovative. Listening to Stravinsky hammer out a piano version of The Rite of Spring, subtitled Pictures from Pagan Russia in Two Parts, he wasn’t sure he’d found it.

Stravinsky imagined a tribe fearful that the spring, on which their survival depended, would fail to thaw the ice and germinate the grain. To ingratiate themselves with the spirits, they sacrifice a young woman who, at the climax of the ritual, dances herself to death.

“Does it go on like this much longer?” Diaghilev asked, wincing at the pounding, repetitive chords, for all the world like the chugging of a giant engine—or, as Stravinsky intended, the stamping of feet in a primitive dance.

Without stopping, Stravinsky snarled, “Only to the end,” and thundered on.

Diaghilev faced a complex decision in which his liking, or otherwise, for the music was only one factor. More showman than aesthete, he thought less about the worth of Stravinsky’s score than about how to fill the enormous new Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.

He was impatient with his regular choreographer, Michel Fokine, and mindful that Nijinsky, who had replaced Fokine as his lover, was eager to develop his choreographic ideas. But Nijinsky’s inventiveness was not matched with diplomacy. Inarticulate and unable to reason with dancers, he bullied them to the point of breakdown.

Diaghilev’s dilemma was classically Parisian. Should he lead with another crowd-pleaser like Scheherazade or Le Spectre de la rose that would wring coos of delight from the rich patrons who took a box for the season? Or with an unknown work almost certain to enrage them? Shrewdly, he decided on the latter and gave Nijinsky his head. Long-term success lay, he reasoned, with a succès de scandale that would sustain his reputation for innovation.

As Le Sacre du printemps had no male lead role for him to dance, Nijinsky poured his imagination and incipient schizophrenia into the choreography. Zelda Fitzgerald, another schizophrenic seized with an urge to dance, described the distorted perceptions that sometimes accompany an attack. “I see odd things,” she wrote. “People’s arms too long, or their faces as if they were stuffed and they look tiny and far away, or suddenly out of proportion.” One sees a similar effect in the shapeless flannel costumes of Le Sacre du printemps, the fright wigs and comic bonnets worn by the peasants, the stamping and spasming of the steps, and the frenzy with which the sacrificial maiden dances to her death.

That the ballet would be greeted with hostility was a foregone conclusion. No opera house, the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées had plenty of cheap seats to accommodate spectators eager for sensation. Some were so ready to disrupt the show that they brought whistles, which they began blowing even before the curtain rose.

Diaghilev gambled that the scandal of that first night would take on a life of its own more durable than the ballet itself, and guarantee full houses for the rest of the season. In 1925 the producers of Revue Nègre, also using the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, would follow his lead, restructuring what had been a relatively staid show to feature a near-naked Josephine Baker doing her goofy version of the Charleston.

To maximize the furor, Diaghilev staged the ballet only twice in Paris and three times in London during that first season, and then shelved it, knowing that speculation and exaggeration would garner far more réclame for the company than any amount of advertising. He wasn’t disappointed. “In Paris in 1923,” he wrote, “I was accosted, as ever, by Gertrude Stein.”

“Ten years, Mr. Diaghilev,” she said. “Can you believe it?”

“Since what, Miss Stein?”

“Since that extraordinary night.”

“I wasn’t aware that you were there,” I said.

“Of course I was there!”

Then she sighed and said, “Ah, Nijinsky.”

He played the same card in 1917 with Parade. To stage, in the darkest moments of the war, a ballet about the circus, designed by Picasso and choreographed by Fokine, with music played on bottles partly filled with water, was seen by many as callous trivialization, but Diaghilev threw more fuel on the fire by handing out free tickets to soldiers on leave and to the rowdiest bohemians in Montparnasse. He also encouraged Fokine to use elements of African-American dance in his choreography, specifically the one-step, described by Harlem Hellfighters bandleader James Reese Europe as “the national dance of the Negro.”

Attending the first performance, young composer Francis Poulenc was as shocked as the rest of the audience: “A one-step is danced in Parade! When that began, the audience let loose with boos and applause. For the first time, music hall was invading Art-with-a-capital-A.” Women tried to blind librettist Jean Cocteau with hatpins, and for subsequent performances sensualists hired boxes in order to fornicate during the uproar. Having correctly judged the French appetite for the roller-coaster sensations of seasonality, the great impresario must have been more than content.