35

Versailles, Île-de-France. 1715. Louis XIV, believing that bathing removes a protective layer that keeps out disease, has washed only three times in his life. Instead, the scent of roses permeates the newly built palace. Visitors are sprayed with rose water, with which the king also douses his shirts. In each room rose petals float in bowls of water, and courtesans anoint themselves with rose oil, each gram of which uses thirty kilos of flowers.

MORE SO IN FRANCE THAN ANYWHERE ELSE IN THE WORLD, POLITICAL survival turns on a gesture.

Its rulers have traditionally displayed a flair for shows and symbols. Versailles under Louis XIV was as gaudy as Las Vegas. Lavish banquets concluded with musical shows that tested the inventiveness of the most skilled designers and performers. That the king himself danced in such performances added to his stature.

The revolutionaries of 1789 showed they had learned this lesson. When they burst into the Bastille on July 14, the ancient prison held only seven inmates, and the rebels were less interested in releasing them than in seizing the weapons stored there. But the symbolism of destroying the ancient fortress made such details superfluous.

In August 1944, Charles de Gaulle led a triumphant walk down the Champs-Élysées to signify the liberation of the city from German occupation. Since June 1940 he had directed a Free French government from exile in suburban London, but the Allies approaching Paris agreed to hang back until he made his lap of victory. It guaranteed his place at the center of national power for the next twenty-five years.

The posters, barricades, and manifestos of student uprising of May 1968 also proved more theater than politics, but as historians downgraded it from revolution to mere événements—“events”—politicians took note of its most important lesson: power would increasingly belong to those who could entertain as well as persuade.

By the time de Gaulle surrendered the presidency in 1969 after ten years in office, younger voters were weary of his stiff, lofty style of government. They wanted a head of state both powerful and human, someone whose hand they might even shake—who could, as Rudyard Kipling urged in his poem “If—,” “talk with crowds and keep your virtue / Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch.”

No modern French politician was a more skillful showman than François Mitterrand, who would serve as president from 1981 to 1995, the longest term of any to hold the office. To counter de Gaulle’s history as wartime leader, Mitterrand traded on his experience in the Resistance. Each year, he led a pilgrimage to the summit of a rocky outcrop in Burgundy known as la Roche du Solutré. Associated with pilgrims since the Middle Ages, the rock had special significance for Mitterrand: he’d hidden from the Germans nearby.

Once he became president and began inviting colleagues and allies to join him and his family and friends in the climb, the press took a keen interest in the guest list. Each year’s walk—evoking Mitterrand’s links to the war, nature, and the national heritage—and those who made it with him became news.

The most significant publicity gesture of Mitterrand’s period in office, however, took place on the day of his inauguration in May 1981 and hinged on a superficially insignificant prop: a single red rose.

Although its national flower is the iris, France has always accorded a special position of honor for the rose. During the Middle Ages, Guillaume de Lorris’s allegorical poem “Roman de la rose” (“The Romance of the Rose”) was popular all over Europe. A young man dreams of entering the walled garden surrounding the Fountain of Narcissus in hopes of stealing a rose. Pierced instead with arrows by Love, he flees, doomed to yearn for the bloom he cannot possess.

The rose became the symbol of love, the bud signifying virginity, the full-blown blossom standing for the woman open to every erotic experience, and the thorns the pain of unrequited or unfulfilled love. In time, the single rose as a token of love declined into a cliché, mocked by Dorothy Parker:

Why is it no one ever sent me yet

One perfect limousine, do you suppose?

Ah no, it’s always just my luck to get

One perfect rose.

The scent of roses suffused the court of Louis XIV, earning it the name “the Perfumed Court.” Marie Antoinette was often painted holding a rose. When Fabre d’Églantine added the name of a rose to his own, he reaffirmed the flower’s importance in the intellectual life of France.

In modern times, the new president of the Republic traditionally begins his first day in office by laying a wreath on the tomb of the unknown soldier. In the afternoon, the mayor of Paris hosts a formal reception in his honor at the town hall.

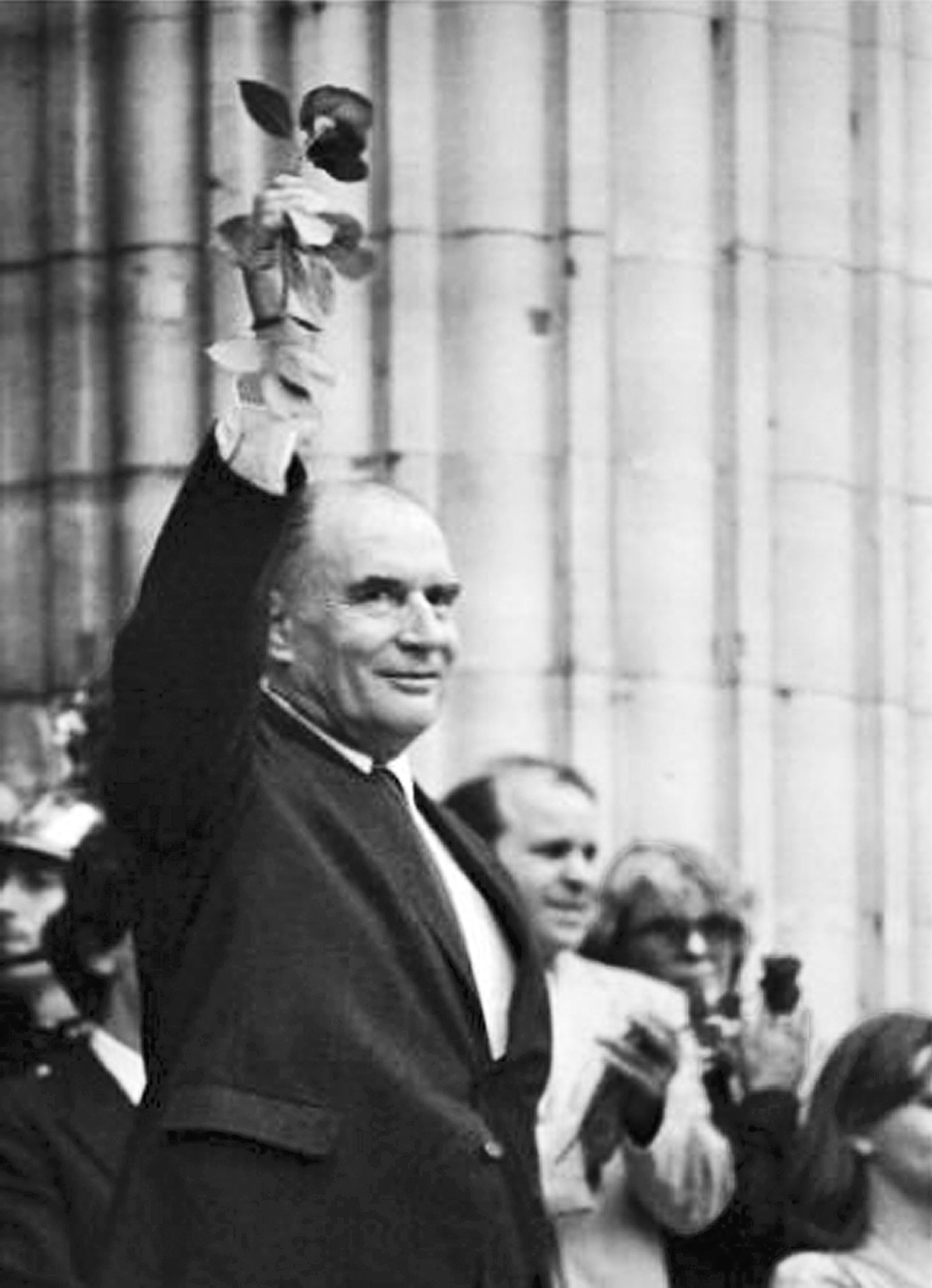

In 1981, Mitterrand broke with protocol. Following the mayoral reception, he didn’t, as was customary, go directly to the presidential palace, the Élysée. Instead, his motorcade crossed the river and climbed the hill of Montagne Sainte-Geneviève to the Panthéon, where the great of France are interred. Leaving the car a block away, he walked alone to the building through jubilant crowds, carrying the symbol of his Socialist Party, a long-stemmed red rose.

As he approached the building’s columned façade, the crowd fell back, leaving him to climb the steps alone (though shadowed by a surreptitious TV team). As he did so, conductor Daniel Barenboim, on the far side of the square, lifted his baton to lead the Orchestre de Paris in the last movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Millions of viewers watched live as Mitterrand crossed the empty floor of the Panthéon (Foucault’s pendulum was taken down for the occasion), paused before its monuments, and descended to the crypt. Striding confidently along its anonymous corridors, he laid roses on the tombs of Jean Moulin, leader of the resistance; socialist pioneer Jean Jaurès; and Victor Schoelcher, who campaigned for the abolition of slavery.

As he stepped out again into the open air, the symphony reached its climax in the famous “Ode to Joy,” which is also, significantly, the anthem of the European Union. Light rain began to fall, but Mitterrand spurned offers of an umbrella, remaining in the open until the music reached its triumphant conclusion: the man of power, respectful of nature and art.

Behind this apparently unrehearsed event lay weeks of planning by an informal committee of media advisers, including Roger Hanin, Mitterrand’s movie-star brother-in-law; TV producer Serge Moati, a specialist in news broadcasts; Jack Lang, his young minister of culture; and historian Claude Manceron.

Manceron, an unlikely recruit to this chic and trendy crew, was then in his late fifties, with a wild white beard spilling halfway down his chest. A childhood victim of polio, he was confined to a wheelchair. His sense of history was acute: it was he who urged Mitterrand to embrace the nation’s oldest traditions and the symbolism of the rose.

François Mitterrand at the Panthéon, 1981.

Anonymous. François Mitterrand. Archives AFP.

Inside the Panthéon, assistants had been strategically placed behind pillars, ready to point him down the correct passages and hand him fresh roses as required. But the millions who watched on television saw only a president who needed no retinue, who knew exactly where he was going but maintained at the same time a decent humility and reverence for tradition.