39

Vert-Galant, Paris 1ere. 12:30 a.m. 15°C. Dark as death, the Seine sucks at the ancient stones edging this tiny park. A willow trails fronds in the water, like a curtain sometimes obscuring and sometimes revealing the lights of the Louvre on the opposite bank. Rats scuttle by the water line, indifferent to both history and art. When all this has sunk back to the ooze, they will survive.

WHEN I FIRST VISITED PARIS IN THE 1970S, BUSKERS WERE OUT NUMBERED by mimes. On weekends, individually or in troupes, they congregated in particular on the sloping plaza in front of the Centre Pompidou, where crowds waiting to enter the exhibitions provided a captive audience.

Marcel Marceau and Bip, his chalk-faced alter ego with the squashed top hat surmounted by a flower, were at the peak of their fame, and some ambitious performers came to Paris to study with him, or with competitors such as Étienne Decroux. Among those doggedly climbing imaginary stairs and struggling to escape from glass cages was future Hollywood star Jessica Lange. She may even have participated in a group mime popular at the time, one I always remembered because of its association with the weather.

In this variation on the slow-motion walk, another mime standby, performers—sometimes singly, sometimes in pairs—battled an imaginary gale. Dressed uniformly in jumpsuits of metallized fabric, they struggled, head down and bent almost double, to advance in the face of a nonexistent hurricane, slogging a few painful steps only to be driven inexorably backward.

Hoping to refresh my memory, I combed the internet for a single image or film of this performance but found nothing. Nor have experts on mime ever heard of it. The phantom wind battled by these performers had swept the pavements clean, leaving no sign of their struggles.

Occasionally, such gaps in information intrigue the science-fiction writer in me. Perhaps they were not mimes at all but travelers from another time, briefly visible to us as they flickered in and out of this universe, only to slip back into an eternal gale howling in another. And why not? I never spoke to those people, nor did they communicate with their audience. Because to do so would offend against the mime’s code? Or because they were not really of our world?

But anyone to whom I mentioned this speculation regarded me with amusement or incredulity, or both. (The surrealists would have understood. Where was André Breton when you needed him?)

I’d put the whole question of imaginary gales out of my mind until chance and the seasons reminded me.

In early January—on the twelfth night after Christmas, to be exact, and better known in the United States as the Epiphany—the French celebrate the Nuit des Rois, or Night of Kings, that day when the kings Gaspard, Melchior, and Balthazar arrived in Bethlehem with gifts for the baby Jesus of gold, frankincense, and myrrh (none of which, probably by intention, figures among the plants and minerals of the Calendrier républicain).

The French celebrate this festival by sharing a rich, buttery cake known as the galette des rois, or “kings’ cake,” made from layers of puff pastry filled with almond paste.

Like most things in France, the eating of the cake, customarily a family occasion, is accompanied by a ceremony. A gold paper crown is sold with each cake, and a tiny ceramic figure, or fève, about the size of a kidney bean is baked into every one.

Once the group is assembled, the galette is cut into as many slices as there are guests and glasses are filled with wine, traditionally champagne. The person who finds the fève in his or her portion (almost invariably the youngest) receives the crown, chooses someone at the table as prince or princess, and drops the fève into their glass. Wine is then poured over it, and to cries of “La reine [or Le roi] boit”—“the queen [or king] drinks”—everyone toasts their health.

After the last Nuit des Rois, Louise gave me a fève. “I got this in the galette at a party,” she said. “It’s more your kind of thing.”

Usually fèves had a religious theme, but this one was decidedly secular: the tiny figure of a blond girl, her skirt blown high up her back, revealing a red thong. The plinth on which she stood was inscribed “Vive le Mistral!”

Certain winds are characteristic of the districts where they occur, mostly because of the damage they cause.

In Sydney the Southerly Buster, a cold squall, barrels out of the Indian Ocean at sunset to overturn yachts and drive the last sunbathers from the beach. In Switzerland the warm, dry wind called the Foehn rushes down the lee slopes of the Alps, inciting to irrational acts the normally staid citizens of such cities as Munich. And every resident of Los Angeles knows the atmospheric disturbances immortalized by Raymond Chandler: “those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks.”

Southern France has the Mistral. The people of Provence, who companionably call it “le mistraou,” will tell you it doesn’t deserve its bad reputation. But they are used to it. To the visitor, this river of air, steady and cold, flowing for days at a time down the valleys of the Rhône, across the swamps of the Camargue, over the Alpes-Maritimes and the coast to the Mediterranean, is a curse, abrading the nerves, destroying the environment, chilling their very souls.

“The Mistral wants you to defy it,” said the poet André Verdet. When it blows, most often as the seasons change, nothing exists between the high blue sky with its smears of cirrus and the fields cowering behind lines of cypresses and palisades of cane. Over millennia it has eroded the landscape, sandpapering the limestone peaks of the Alpilles into crags to which such towns as Les Baux cling like survivors from a medieval fable, inviting a sky filled with dragons.

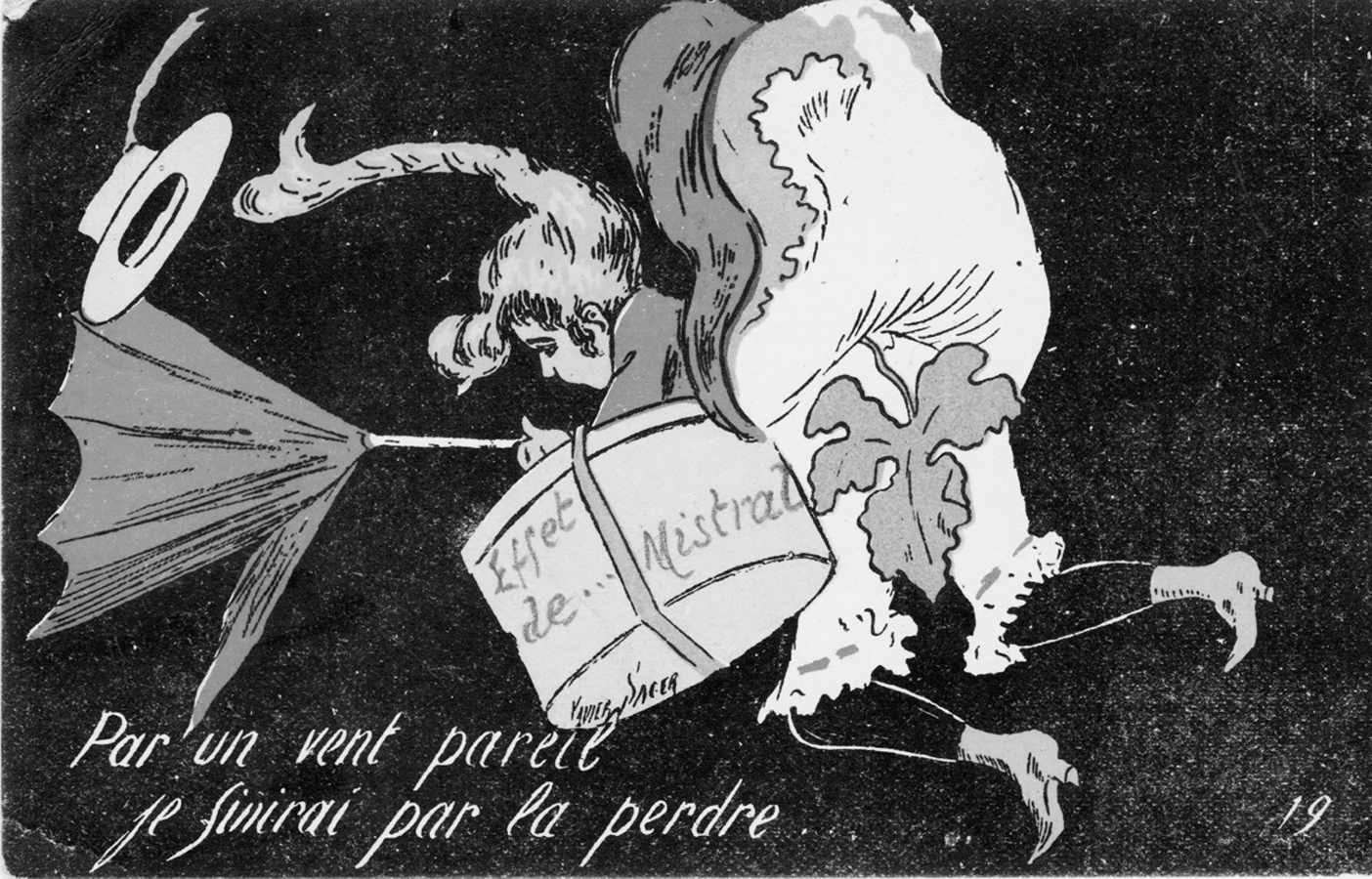

Caricature of the Mistral, 1905.

Sager, Xavier. Caricature of the Mistral. 1905. Author’s collection.

Watching film of pedestrians battling the Mistral, heads down, hands clutching hats or holding down skirts, reminded me of those mime artists fighting a phantom wind on the slope before the Centre Pompidou. Maybe the person who choreographed their performance didn’t come from anywhere as remote as another dimension—just from Arles or Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where resistance to an implacable wind was part of the way of life.

Antique engraving of the Mistral.

Anonymous. Des Vents; de la sphere. Figure LXIII. Woodcut of storm with lightning. Author’s collection.