44

Reid Hall, Paris 6me. November 2017. 6°C. Hollins University of Roanoke, Virginia, has invited some distinguished expatriates to speak at a lunch for a group of visiting alumni. During a discussion onstage between Terrance Gelenter and Diane Johnson, a member of the audience asks, “What do you miss most about the United States?” Both reply in unison, “Mexican food.”

“IT’S SAD,” SAID TERRANCE GELENTER.

Across the table at the Chez Fernand, his bearded face, never notably cheerful, did look more than usually doleful.

“Cheer up,” I said. “If it makes you feel any better, I’ll pick up the check.”

Normally this was enough to lighten his mood, but not today.

“I didn’t mean I was sad,” he said. “Though I am. I meant SAD. Seasonal Affective Disorder. It always affects me at this time of year. Paris starts to get me down.”

“Really?”

SAD results in part from a lack of sunshine. I looked out at narrow, restaurant-lined rue Guisarde. Like most such streets in Saint-Germain, it only sees direct sunlight around midday, but the locals didn’t seem to mind. Living in perpetual shadow encourages a collective good humor, a sense of us-against-them that has seen them through tough times, much as the “Britain Can Take It” spirit sustained London through the Blitz.

But Gelenter was from suburban New York, so allowances had to be made. As Thomas Wolfe suggested in one of his novels, only the dead know Brooklyn. A certain melancholy was to be expected.

“What form does it take, this SAD?”

“Oh, you know, anxiety, depression, sleeplessness . . . It’s a recognized condition. Say, do you think the girl heard you order the wine?”

Just then, he looked past my shoulder and his eyes lit up. I guessed the waitress was heading in our direction.

“Ah, ma jolie . . .” Half rising, he reached out his hand. I thought for a moment he might clamber over the table, and me as well, in his haste to get to her. Abruptly he had become the boulevardier par excellence.

This was a performance polished to a gleam by repetition. He probably didn’t realize any longer that he was doing it. Seeing an attractive woman between the ages of fifteen and ninety—policewoman, nun, mother of eight: it didn’t matter—he was energized as if a switch had been thrown, and suddenly there was Terrance le Coquin (Naughty Terrance).

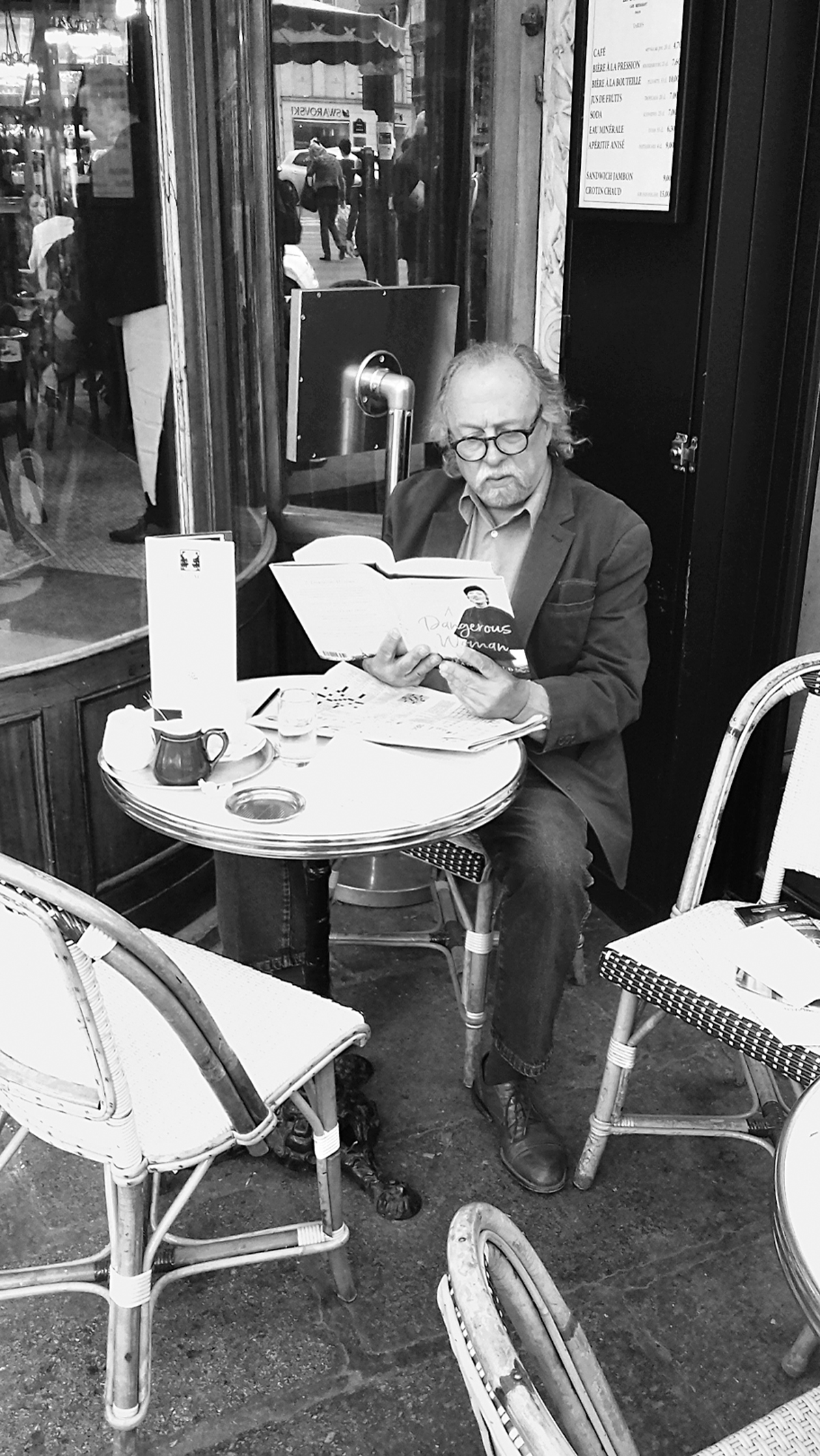

Terrance Gelenter in repose.

Bonneau, Francis. Terrance Gelenter.

What would he do if one of these women said “OK” and hitched up her skirt? I suspected he would run a mile, but so far I’d never been around when this happened, if it ever did.

To distract him, I took the pichet of Bordeaux and poured each of us a glass. For a moment he wavered, his barrage of double entendres challenged by the appeal of a drink. Eventually the bird (or rather, glass) in the hand won over the bird who remained beyond his grasp.

“Salut,” he said, settling back into his chair and taking a swallow.

“Salut,” I said. “So . . . you can’t sleep?”

“Yeah. It’s a bêtise. The other night, it was so bad I got out of bed and went for a walk.”

“What sort of time was this?”

“I don’t know . . . two or three.”

“You went walking at two or three a.m. because you were depressed?”

“Sure. Why not?” He emptied his glass and reached for the pichet. “And to see who I could pick up, of course.” He opened the menu. “How’s the boeuf bourguignon here?”

Walking the streets at 3 a.m. wasn’t as novel for me as I suggested. All my life I’ve worked best after dark, rising regularly at 4 a.m., brain humming with ideas. People like me relish the night’s peace and tranquility, its quality of repose. The English term “night owl” belittles us. Unlike that cruising predator of the woods and fields, we spend our nights in reflection, reading, writing, and, to facilitate the process, occasionally roaming empty streets. Acknowledging our affinity with the world of dream, the French call us noctambules (nightwalkers).

Woody Allen is the latest recruit to our group. In his film Midnight in Paris, a restless American screenwriter played by Owen Wilson gets lost during a late-night stroll and is picked up by a vintage car that carries him back to the Paris of Hemingway and Fitzgerald and Kiki of Montparnasse.

The film is charming enough, but others have done it better: Philippe Soupault’s Last Nights of Paris, Louis Aragon’s Paris Peasant, or Henry Miller’s Quiet Days in Clichy with photographs by another insomniac, Gyula Halász, alias Brassaï.

The list of noctambules goes back to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who found little to draw in Paris by day but ample material in the gloom and glare of Montmartre’s nights—which also hid his physical deformities. He didn’t lack company. Prostitutes and their clients came out as the sun went down. So did the men who pasted his posters to Montmartre’s walls—followed closely by collectors, who peeled his vivid paper masterpieces off the brickwork before the glue had time to set.

Paris is no twenty-four-hour city like Hong Kong, Tokyo, or Los Angeles. You will look in vain for an all-night supermarket, cinema, or restaurant. The average Parisian returns home at night, eats dinner, watches TV, and goes to bed. That some people are of the day and others of the night is acknowledged, but not catered to. We noctambules must make our own arrangements.

As a matter of form, the city administration discourages us. Sunset sees public parks locked. Restaurants close around midnight, cafés at 2 a.m.; cooks and waiters have home lives too. The Métro ceases around 1 a.m. Yet as one door closes, another is left slightly ajar. Intermittent Noctambuses (night buses) serve the sleepless, and a few cafés stay open all night, ostensibly for the benefit of newspapermen and others who work unsocial hours but in fact havens for the restless and, in the words of one habitué, “people who want to be alone but need company for it.” In the most famous of these twenty-four-hour cafés, Montparnasse’s Le Sélect, James Baldwin wrote most of his first novel, Giovanni’s Room, and Hart Crane, gifted poet of “The Bridge,” drank away his nights, brawling with waiters over the bill and more than once ending up in jail.

Though I was only twelve when I first read Dylan Thomas’s poem “In My Craft or Sullen Art,” I recognized instantly a desire shared with him to “in the still night / When only the moon rages . . . labour by singing light.” The dark was always my home. In a country of blazing sun, I gravitated perversely toward the lightless space of Astounding Science Fiction magazine, the ruined Vienna of Graham Greene’s The Third Man, and Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles, where “the streets were dark with something more than night.” Murmuring at my ear as I read was a shortwave radio broadcasting Voice of America’s nightly program of modern jazz, a thread of sound connecting me to Minton’s and Birdland and the Lighthouse at Hermosa Beach. I was home.

Jazz, that ultimate music of the night, is the Esperanto of the noctambule. One winter night not long after I moved to France, I heard an a cappella vocal trio called Les Amuse-Gueules perform in a bleak municipal hall by the Canal Saint-Martin. Their repertoire included Thelonious Monk’s bebop classic “Well You Needn’t.”

You’re talkin’ so sweet well you needn’t

You say you won’t cheat well you needn’t

You’re tappin’ your feet well you needn’t

It’s over now, it’s over now.

I felt like a traveler in a remote corner of the world who hears someone speak his own language. How often, talking to some French writer or artist of my generation, I’d seen their eyes light up at the mention of a favorite track. “‘A Night in Tunisia’? Yes, of course I know it. Which version do you prefer, Monk’s or Dizzy Gillespie’s?” Until then, it had never crossed my mind that people in France heard those same Voice of America broadcasts, that existentialism evolved to the music of Monk, Miles Davis, and Charlie “Bird” Parker.

Jazz gave me something in common with Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Boris Vian, and Juliette Gréco. It ignored intellectual disciplines. In 1949, Charlie Parker chatted with Jean-Paul Sartre at the Club Saint-Germain. “I’m very glad to have met you,” he told Sartre as they parted. “I like your playing very much.” A writer may improvise just as powerfully with words and ideas as a musician can with an instrument.

Modern jazz is an art of the night. So is sex. “Night, beautiful courtesan,” mused Apollinaire. In “Paris at Night,” Jacques Prévert wrote:

Three matches, one by one struck in the night

The first to see your face in its entirety

The second to see your eyes

The last to see your mouth

And the darkness to remind me of all these

As I squeeze you in my arms.

“I couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” murmured my actress friend Anna. She was describing some neighbors she’d met just a few doors down the street in the early hours of the morning.

We were sitting in a café on rue François Miron, a narrow thoroughfare that snaked along the edge of the Marais, the most medieval of the inner districts. Its churches and hôtels particuliers had already been old and leaning when François Villon reeled among them, shouting, “We must know who we are. Get to know the monster that lives in your soul; dive deep and explore it.”

I thought I knew who these people were, but the following Sunday around midnight, stepping out onto the narrow sidewalk in front of her building, I turned right and walked toward the knot of people standing outside No. 14. A light rain sifted down through the streetlights, adding a sheen to the ancient stones.

The seventeenth-century exterior of No. 14 looked unremarkable. Exposed beams and crooked windows gave no hint that it housed one of Paris’s most popular sex clubs. On the first of its three floors, clients could enjoy a buffet supper, dance in the disco, and drink at the bar—and then they could descend to the lower levels to test the limits of what was possible between consenting adults.

Ironically, one of the few forbidden acts was smoking. To light up, patrons had to ascend to the street. About a dozen, mostly women, huddled against the façade to escape the rain. Most wore long coats, a few of them fur, but I spotted a Burberry, and one woman was tightly wrapped, Marlene Dietrich–like, in a belted garment of black leather that brought to mind horse whips and handcuffs. All wore heels so high that to walk more than a block invited a broken ankle. Not that any of them needed to walk. For each, a chauffeur or obliging husband dozed in a nearby side street or parking lot, half listening to late-night radio, awaiting their summons.

As I passed, a few of the women turned away and lowered their voices, but most continued to murmur into their cell phones. I caught snatches of conversation in German, English, French. “. . . thought I was going to faint . . . son bite . . . enorme, ma biche, je te jure . . .”

Anna had been incredulous when I explained about échangiste clubs. I found them all too easy to understand. These were the people for whom Dylan Thomas had written:

. . . the lovers, their arms

Round the griefs of the ages,

Who pay no praise or wages

Nor heed my craft or art.

He would have rejoiced in the existence of these fellow noctambules, as would Prévert and Aragon and Villon. As did I. Respect must be shown.

“How about another bottle?” I said to Naughty Terrance.