Chapter 2

A Confucian society

For five centuries from 1392 to the arrival of modern imperialism in the late 1800s Korea underwent a continual process of cultural change and integration under the Chosǒn state and its Yi ruling family. The state’s territorial boundaries stabilized to where they are today, its population became ethnically homogeneous, and their culture became profoundly Confucian. The process by which the inhabitants of the peninsula developed into a single people with a shared culture and identity, one clearly recognizable today as ‘Korean’, had begun long before. Under Chosǒn it was largely completed.

The establishment of the Chosǒn state by Yi Sǒnggye in 1392 did not mark a sharp change in the direction of Korean history. It was rather the same old Koryǒ kingdom under a new dynasty with a new capital Hanyang (today’s Seoul) 30 miles (50 km) south of the old one, Kaesong. For the most part, the new dynasty was ruled by the same families and officials that had served in Koryǒ joined by men of military background like Yi and by some scholars from lesser aristocratic lineages. Yi Sǒnggye and his son T’aejong (r. 1400–18) pursued the same policies as had the early kings of Koryǒ—abolishing private armies, reforming the tax system, and strengthening monarchical power. There were some institutional changes. T’aejong was able to exert more direct central control over the countryside through the use of powerful royal governors to administer the eight provinces. Furthermore, unlike his Koryǒ predecessor, he was able to place centrally appointed magistrates to head all the counties and prefectures. Most significantly, Korea under the five centuries of Chosǒn changed as generations of reformers carried out efforts to bring the political and social order in line with Confucian principles. Gradually, through their persistent efforts, Confucian-based cultural norms pervaded every social class giving a greater uniformity and unity to Korean society.

Creating a Confucian state

Under the Chosǒn dynasty Neo-Confucianism became the state ideology. What was once a Buddhist-Confucianist state became a Neo-Confucianist one. Confucianism, a system of ethical, social, and political thought, was not new to Korea. It had been part of the mix of Chinese learning that had been entering the peninsula since the Three Kingdoms period. Confucian teachings became part of the curricula for the civil exams in Koryǒ. During the Mongol period, however, Korean scholars became aware of a new reinterpretation of Confucianism that had flowered in China during the 11th and 12th centuries. Koreans called it by varying names, including ‘study of the Way [of Heaven]’, but today modern scholars refer to it as Neo-Confucianism. Thinkers in the Neo-Confucian tradition aimed at removing what they regarded as the superstitious Buddhist, Daoist, and other corruptions to the line of teachings associated with Confucius and his followers. While in reality Neo-Confucianism was a reinterpretation of Confucianism that made it a more all-embracing belief system with many aspects of a religion, its adherents believed they were recapturing and reviving the ancient wisdom of Confucius and the sages before him.

Korean advocates of Neo-Confucianism were especially dogmatic, intolerant of divergent views and insistent on the need to remodel society based on its principles. They sought nothing less than to create a great virtuous and harmonious society in accordance with the Way of Heaven. Most of the core principles emphasized by these Neo-Confucianist reformers—loyalty, hierarchy, respect for tradition, the importance of family, and the need for all members of society to adhere to the roles assigned to them by the laws of nature—were not new. But their intolerance of other beliefs was a break with the Korean tradition of accepting multiple forms of spirituality. Buddhism, shamanism, nature worship, elements of Daoism, as well as Confucianism, had coexisted and borrowed from each other. Individual Koreans might follow them all. The reformers, however, were staunchly opposed to Buddhism which they saw as self-centred, focusing on oneself and not one’s duty to society; and they regarded monks as parasitical, contributing nothing to society. At their insistence, the state closed temples in the capital and banned monks from public affairs. Most temples were stripped of their slaves and landholdings. Under the relentless attacks by Neo-Confucianists and the state they increasingly dominated, Buddhism retreated into the margins of Korean society. Although still widely practised, it was no longer at the centre of public life.

The Neo-Confucianists placed a great deal of importance on the role of government in creating a virtuous society. For them the new dynasty was an opportunity to reform government in order to reform society. Neo-Confucianist scholars such as Chǒng Tojǒn were among the most ardent supporters of the Chosǒn dynasty and an important part of the coalition that brought Yi Sǒnggye to power. The reformers then worked to see to it that the monarch, his court, and his public servants carried out their roles in accordance with the Way. They pursued their project of bringing the state in line with Confucian principles less by radical institutional change than by reforming the inherited organs of the state.

An important vehicle for their project was a set of three institutions known as the Censorate. Borrowed originally from China, the Censorate consisted of boards of scholars who examined the backgrounds of potential appointees to state office and their families. Candidates for office not only needed records of unblemished moral character but had to come from families which were free from scandal. Even a wayward grandparent could be grounds for disqualification. They also reviewed the conduct of officials while in office to see that they were acting properly, not just in their public but also in their private life. Another of the Censorate’s major functions was to monitor the conduct of the king. Censors frequently admonished monarchs for unethical or otherwise improper behaviour. In short, they were the moral guardians or moral police of the state. Since censors were well schooled in the tenets of Neo-Confucianism and firm adherents of them, the Censorate acted as one of the institutional bases for the great undertaking of making Korea a truly Confucian society.

The reformers placed importance on the ruler as the upholder of the moral and social order of society. He did this through his personal example of virtuous conduct and by governing with a concern for the welfare of his subjects. They insisted that the king attend daily lectures by scholars to remind him of his moral duties, and that his words and conversations with officials be recorded by historians for posterity. Compiling history was an important project since it could be used to educate future rulers. Another instrument for promoting a virtuous government was through the civil service exams. These were especially important, not only to see that men of merit served in government, but since their content was based on the study of canonical texts they were a major means of indoctrinating the elite into Confucian principles.

Creating a virtuous government that reflected the Way of Heaven proved a long-term project. Fifteenth-century officials, even monarchs, continued to consult Buddhist monks and shamans; and kings often failed to attend the daily lectures. Yet, over time the state and the ruling class adopted most elements of the official interpretation of Confucianism promulgated by Neo-Confucian reformers. Deviation from this was ruled heterodoxy and dangerous. Although the 16th century produced some first-rate Confucian thinkers such as Yi Hwang (better known as T’oegye) and Yi I (better known as Yulgok), in general Korean intellectual life was dominated by a dogmatic rigidness not found in contemporary China or Japan.

As the state became more Confucian, the upper class became more linked to it. Even more than was the case in Koryǒ, serving the state became the principal means of confirming and enhancing status, of protecting wealth and acquiring power and influence. The main way to gain office was through the state examinations. Each of the country’s 300 counties had a state-sponsored school to prepare young men for the exams and educate them in the principles of the Way. These were supplemented by hundreds of private academies. The law of avoidance meant that if a young man passed the exams and gained an official post, he was not allowed to serve in the home area. Thus, the near universal focus on the exams, the common curricula, the circulation of the officials around the kingdom, and the networks of school ties acted as a process of homogenizing the yangban. This process of creating a like-minded, state-centred elite was reinforced by the fact that almost all spent some time in Seoul.

One way, however, that Chosǒn Korea deviated from Neo-Confucianism was the importance of hereditary status. This was a contradiction with the Confucian belief in government by merit. But efforts by some reformers to open public office to those of humble status were not successful. Rather the Chosǒn state was the enforcer of social ranks. Neo-Confucian literati were concerned that everyone should know their rank so that order could be maintained—so much so that they developed the hop’ae system in which people wore identity tags indicating their status. Yangban wore yellow poplar tags, commoners small wooden ones, and there were big wooden ones for slaves. Yangban serving as high-ranking officials wore ivory identity tags, lower-ranked officials ones of deer horn.

Creating a Confucian society

Korean Confucianism was distinguished from that of its neighbours not by doctrine but by its careful and often rigid adherence to the rituals, and by the persistent efforts of reform-minded scholars and officials to make most social institutions adhere to its principles. Reformers placed special emphasis on the family and on making sure that each person correctly performed his or her role in the family. Rituals and ceremonies reinforced these roles. These were to be carried out in accordance with canonical texts such as Family Rituals by the 12th-century Chinese scholar Zhu Xi. Older Korean customs such as those associated with marriage were altered to conform to the rituals and practices laid out by these texts. Another concern of Neo-Confucianists was that everyone carry out his or her duty to marry in order to perpetuate the family line. This become so important that young people who died before marriage were often married posthumously to another boy or girl who also died prematurely.

The centre of Korean ritual life became the rites to family ancestors or chesa. This not only emphasized the importance of family lineage but also the fundamental principle of filial piety (hyo). Filial piety, the respect and loyalty to one’s parents, was the basis for all loyalty and duty which were virtues necessary to maintain a stable, harmonious society. To reinforce respect for and loyalty to not only one’s parents but all one’s direct ancestors the state mandated that all perform the chesa. It also required three years of mourning when a parent died; their death date was commemorated annually thereafter by a special ceremony.

Neo-Confucianist reforms greatly impacted the relationships between men and women. Women had to be subservient and obedient to men, and the distinction between men and women had to be strictly maintained. In the 15th century laws were passed prohibiting women from riding horses, playing polo, or engaging in activities that were part of the male sphere. Women lost the right to divorce their husbands and to gain custody of their children. They no longer shared inheritance equally with their male siblings, could no longer keep their property in marriage, and could not mix freely with men. Women had to be chaste and loyal to their in-laws. Widows were no longer allowed to remarry since they were to be loyal to their husbands for eternity. Girls were often married in childhood. If their husbands died early, even before they were fully grown adults, which was not uncommon in pre-modern times since death rates were high, they were still prohibited from remarrying. Women were held to a high standard of chastity. Any questioning of a woman’s virtue could bring dishonour to her entire family. Young girls were sometimes given a p’aedo, a small knife to commit suicide with should that happen.

The spheres of the two genders were kept so separate that houses often had different entrances—one for men and one for women. Inside the home there were men’s and women’s quarters separated by the kitchen. Late in Chosǒn, concern for keeping men and women apart went even further. In Seoul, to make sure that they did not mix in public there were certain hours of the day marked by ringing a bell when only women could be on the street. At all other times, only men could move about. Many upper-class women lived secluded lives behind high walls with little exposure to men other than relatives. Even male physicians could treat female patients only from behind a screen, using the vibrations of a string to feel their pulse. Elite Korean women went from living among the least to among the most socially restricted lives in Asia. There were some exceptions such as kisaeng, female entertainers who played a role in society similar to Japanese geisha, and mudang, female shamans; but both were of low social status (Figure 3).

3. Korean yangban with kisaeng, 18th century.

Strict adherence to Confucian norms of behaviour helped to distinguish the yangban elite from the commoners who did not have the luxury of adhering to all its rules. Men and women had to work together in the field at planting, harvesting, and other busy times, and commoners could not afford all the proper rituals or the three years of mourning. Yangban men with their white clothes, derived from these long periods of mourning dress, and with their black horsehair hats were clearly differentiated from commoners. Mastering the Confucian classics and adhering to the correct rituals helped define being members of the elite, since others did not have the time and luxury to do so.

Most Koreans were peasants living humble lives. Many owned land, but often too little to support a family so that they also worked lands owned by the elite. They lived in their own sections of villages and towns separate from the aristocracy and were excluded from public life. Between the commoners and the yangban was a small hereditary in-between class consisting of clerks who staffed the local government offices and skilled specialists who took special exams to become physicians, geomancers, and interpreters. At the bottom of society were the outcaste groups such as butchers and tanners, and slaves. Slavery was far more common in Korea than in its East Asian neighbours. Both aristocrats and the state owned slaves. In early Chosǒn perhaps one-third of the population were slaves. However, in the 18th and 19th centuries the institution declined. State-owned slavery was abolished in 1801 but some private slaves still existed until the 1890s.

Yet, despite the rigid gaps between yangban and the other social classes, Confucian customs and values were absorbed by the non-elite groups. Yangban gave regular sermons to villagers on Confucian principles, and many commoners sent their sons to village schools, sǒdang, where they were taught basic literacy by reading Confucian works. Ordinary people began offering rites to the ancestors and adopting the terminology of filial piety and distinction between the sexes. A widely shared respect for learning contributed to rising male literacy rates among commoners, although the civil exams were effectively closed to them. By the 18th century, if not earlier, pervasive use of the language of Confucianism and a devotion to its rituals was characteristic of Koreans of all social classes.

Its greater adherence to an orthodox version of Confucianism may have contributed to another way Korea differed from its East Asian neighbours—its lack of commercial development. Compared to China or Japan, the country was less urbanized, the merchant class smaller and less wealthy, and the volume of trade was more modest. Geography is one explanation for this. China, like Europe, had great rivers that facilitated transport; Japan had navigable coastal waters linking population centres, most significantly the Inland Sea. Korea had neither. The mountains and hills made overland travel difficult, the rivers did not connect regions of the country, and then there were the high tides and sandbars that made coastal navigation challenging. As a result, trade was often over narrow mountain footpaths where pedlars carrying A-frame backpacks were their own beasts of burden.

But geography can be overcome, and Koreans were able to construct a fairly centralized and uniform government in spite of living in a country of valleys and little plains separated by mountains. Other factors that contributed to this modest level of commercial activity included the policy of the Chosǒn state to discourage the mining of precious metals lest it attract the attention of China. This hindered the production of coins. Instead, transactions were often conducted in bolts of cotton or other cumbersome mediums of exchange. The most common explanation given for Korea’s lack of a vigorous commercial sector, however, is the Confucian disdain for commerce, especially among the dominant yangban class. Yet there were signs that attitudes were changing in late Chosǒn; a number of scholars called for the need to develop commerce and the government began to increase the use of money transactions and ended restrictive merchant licensing practices.

Chosǒn’s Confucianization can be exaggerated. Buddhism receded but did not disappear. The mountain monasteries continued to provide a safe retreat from the stresses of life; and Buddhist priests were often called upon to preside at funerals. Confucianism acknowledged no gods, afterlife, or eternal soul. Nonetheless, most Koreans lived a world inhabited by kwisin (spirits). There were spirits of the dead that could haunt them, bring disease and misfortune, and required a shaman to placate them. Even yangban and kings sometimes called upon shamans to deal with them. Spirits lived in trees, rocks, and striking geological features. Almost every temple had a shrine to Sanshin the mountain spirit. Household gods such as those of the kitchen, the gate, and those dwelling in storage jars were given offerings by women in household rituals. Each village had a shrine for the local guardian god. Buildings and gravesites were situated according to p’ungsu (geomancy), the belief that certain configurations of land were auspicious or had spiritual power. Seoul itself was laid out with North Mountain protecting the city from malevolent forces from the north and the Han River safeguarding it from the south. Yet spirit worship remained a mostly private affair and never matched Confucianism for importance. Only Confucianism served as an ideological basis for government, ethics, and social norms.

The zealousness with which Koreans adopted Neo-Confucianism gave their culture a distinctive nature while the adoption of its beliefs and values by all social classes contributed to the uniformity of their society. To a greater degree than with their East Asian neighbours, the centrality of Confucianism was a core feature of Korean cultural identity. Many Confucian beliefs and values were challenged and openly denounced by Koreans in the late 19th and 20th centuries as Korea underwent a long, painful process of modernization. Yet the influence of Confucianism was still apparent in both North and South Korea in the 21st century.

Securing the borders, becoming a homogeneous society

Under the early Chosǒn kings Korea’s borders became fixed to where they are today. These boundaries were established as part of the effort to secure their frontiers. To the south, early Chosǒn kings dealt with the threat from Japanese pirates known as waegu. In 1443, King Sejong (r. 1418–50) reached an agreement which allowed Japanese merchants to trade at authorized southern ports and the raids abated. To the north King Sejong had to deal with raids by Jurchens tribal folk based in Manchuria. In order to protect the country he pushed the border further north to the Yalu and Tumen Rivers. Except for minor adjustments made in 1712 after Manchuria had become incorporated into the Chinese Empire, this is still the boundary between North Korea and China. The Chosǒn state encouraged those Jurchens who lived within the new boundaries of Korea to marry Koreans and adopt Korean culture. This was not completely successful at first, and there were two rebellions by Jurchen minorities in the 15th century, but eventually the tribal peoples in these frontier areas were absorbed into Korean society. The state then settled much of the sparsely populated north with Korean families from the southern part of the country. These were mostly poor landless peasants, and people of slave or outcaste background who now had the opportunity of owning their own farms. Settling the north was a gradual process, especially difficult in the remote, rugged Hamgyǒng province in the north-east with a climate and topography that made agriculture precarious. Yet, eventually, because of this policy of assimilation and settlement, the area became integrated into the rest of Korea.

Since few Koreans ventured beyond the Yalu and Tumen the political boundaries of Korea became the ethnic-linguistic boundaries as well. By the 17th century the Korean language had evolved into modern Korean, the language spoken today. Regional dialects existed but they were mutually comprehensible, more so than was the case in many societies of similar size such as Italy or Vietnam. There were no known speakers of any other language in Korea, nor, with the assimilation of the Jurchens, any ethnic or tribal minorities. Few societies in the world were so ethnically and linguistically uniform.

At the same time, Korea became a more culturally uniform society. Symbolic of that culture was the creation of Hangul, the Korean alphabet, in the 15th century. Koreans mainly wrote in classical Chinese. When they wrote in Korean they did so with Chinese characters, developing several methods of doing so. The problem was that the two languages could hardly be more different. Under King Sejong a committee of scholars developed a phonetic alphabet that not only accommodated the complex Korean sound system but based the letters themselves on stylized shapes of the tongue and mouth when making a sound. The work was finished in 1443 and was promoted in 1446 with a manual Hunmin Chǒngǔm (‘correct sounds for instructing the people’). In modern times Hangul has become a symbol of national pride and uniqueness. However, the yangban class preferred to write in classical Chinese, labelling the Korean alphabet the ‘vulgar script’ or ‘women’s script’, implying that it was only good for untutored females. It was only in the 20th century that it became the main form for writing Korean and a symbol of Korean identity and cultural achievement.

While the distinctive Hangul writing system did not come into universal use during the Chosǒn period, many other customs and traditions marked the cultural boundaries between Koreans and non-Koreans. All Koreans wore distinctive clothes derived from early China and Mongol era dress, quite different from the clothes worn by men and women in contemporary China or Japan. Koreans lived in homes with interior and exterior designs that set them apart from their East Asian neighbours. These homes were heated in the cold winters by the system called ondol in which floors were warmed. While much of Korean art, literature, and music was derived from China they gradually evolved into more uniquely Korean forms.

Chosǒn in East Asia

Korea’s often troubled relationship with its neighbours contributed to a common sense of Korean identity. Korea could never escape the reality of being surrounded by bigger, more powerful, and potentially dangerous neighbours. Chosǒn’s efforts to cope with the challenges from them strengthened popular attachment of Koreans to the state and helped nurture a sense of collective identity among them.

After the frontiers were secured in the 15th century Chosǒn’s next great threat came in the late 16th century from Japan. In 1592, Hideyoshi Toyotomi, a warrior who became ruler of Japan, carried out a plan to subdue Korea. His aim was to use the peninsula as a base for conquering China. In what was the largest overseas invasion in history up to that time, a quarter of a million men began crossing the Korea Straits, landing in Pusan. Caught by surprise, the unprepared Koreans were quickly overrun by the well-trained Japanese forces equipped with muskets as well as swords and pikes. In just three weeks they were in Seoul. The fleeing court called on China for help. Ming China, alarmed by the prospect of a new threat near its north-eastern border, responded immediately. Chinese forces stopped the invaders at Pyongyang. Eventually the Japanese were forced to withdraw to the southern parts of Korea. From there they launched a renewed invasion in 1597 but this time the better-prepared Koreans along with their Chinese allies were able to contain the Japanese advance. In 1598, Hideyoshi died and the Japanese withdrew from the peninsula.

The invasion devastated Korea, and its memory has been used in modern times to inflame anti-Japanese sentiment, while China’s intervention resulted in Chosǒn’s gratitude and reverence for the Ming dynasty. The war also produced one of Korea’s great heroes, Admiral Yi Sunsin (1545–98). Yi supervised the construction of a fleet of ships that carried on a successful naval campaign, sinking hundreds of Japanese vessels and disrupting the Japanese supply lines. One of Admiral Yi’s innovations was the kǒbuksǒn ‘turtle ship’, believed by many to be the world’s first iron-clad vessels, pre-dating the Monitor and the Merrimack in the US Civil War by more than two and a half centuries. These proved resistant to Japanese naval gunfire and were designed to ram and sink enemy ships. Admiral Yi Sunsin died in combat toward the end of the conflict, becoming one of Korea’s most admired figures. Following the failure of the court to protect the people against the invaders, many ordinary Koreans organized their own resistance. Their efforts against a foreign invader may well have contributed to their common identity as a Korean people.

From the early 17th century to the late 19th century, Korea maintained peaceful relations with Japan, trading and occasionally sending a diplomatic mission to Edo (Tokyo). The Korean visitors to Japan found the society falling short of being fully civilized. Their knowledge of and adherence to Confucian principles were inadequate, the sexes mixed too freely, and they claimed to have an emperor when there could be only one emperor presiding under Heaven, the one in Beijing. Koreans maintained more tentative contact with other countries such as Vietnam as well as with Okinawa and some other South-East Asian lands. In general, the Koreans regarded these more distant neighbours as also more distant from adherence to the Way, which reinforced pride in their own achievements.

Chosǒn’s most important relationship was with China. Koreans often identified their land by reference to its geographic position with its giant neighbour. This is clear from the names they called their country—Haedong (‘East of the Sea’), or Taedong (‘Great East’) both referring to being east of China, or ‘Chosǒn’, which can be interpreted as meaning morning country—again loosely translated as ‘east of China’. China was ‘Chungguo’ or ‘Chunghwa’ ‘Middle Kingdom’ or ‘Central Civilization’. Korean maps showed China in the centre of the world; officials regarded the Chinese emperor as the only emperor, a ruler without a peer. His approval was important for Korean kings to legitimize themselves. That their kingdom was right next to China, and that their ambassadors in Beijing were often given a seat closest to the emperor on ceremonial occasions, was a source of pride and reassurance that they were near the centre of civilization. And China was the home of the ancient legendary sage emperors, of Confucius and Mencius, and of the highly revered Neo-Confucian thinker Zhu Xi.

Seeking the legitimacy that recognition from the Chinese emperor conferred, Korean kings sent regular tribute missions to Beijing. Over time these increased from one every three years to three a year. Hundreds of officials and their staff went on them, providing opportunities for trade, and for keeping up with the intellectual, cultural, and fashion trends in the Middle Kingdom. Korean admiration for China was only reinforced by the gratitude they felt for the Ming dynasty’s intervention that saved them from Hideyoshi’s hordes.

But in the mid-17th century developments challenged the way Koreans thought about China. In the early 17th century a Jurchen group called the Manchus founded a new state in Manchuria and began the conquest of China. The Manchus twice invaded Korea in 1627 and 1636, forcing the Koreans into paying tribute to them and breaking off ties with the Ming. In 1644, the Manchus took control of Beijing and established the Qing dynasty. Under this new dynasty the Chosǒn court resumed its tributary relations with China, dutifully sending its tribute missions. However, the Koreans were uneasy with the Qing since they regarded the new dynasty as ‘barbarian’. While outwardly carrying out their traditional role as a loyal tributary, the Korean court secretly maintained a shrine to the Ming. They dated documents according to the old Ming calendar not the new Qing, thereby symbolically retaining loyalty to the old dynasty and delegitimizing the new one.

The Chinese Empire had in practice always been a multi-ethnic one, and imperial dynasties were often at least partly of Inner Asian origin. Furthermore, the Qing were great patrons of Confucianism and much of Chinese culture, which flourished under their rule. Yet Koreans continued to see the ruling dynasty as semi-barbarian, and they looked down on the Chinese elite as those who had compromised their principles and their dignity by obeying the alien Manchus. Not all Koreans held the Qing Empire in disdain. In the 18th century some Chosǒn writers praised the commercial development in China. In general, however, after the mid-17th century Koreans saw China as a society that had deviated somewhat from the path of civilization by submitting to barbarian rule.

Late Chosǒn

From the late 17th century, the educated elite of Korea began to re-evaluate their society and its place in the civilized world. China was under the rule of barbarians, and the Japanese were never fully civilized, so that Koreans were now the truest adherents to the Way; their society was the last bastion of Confucian principles in their purest form. Koreans still held great deference toward China as the home of civilization, the elite still composed in Chinese, and their writings were filled with references to classical China. Scholars showed interest in new intellectual trends such as Evidential Learning of Qing China, which Korean envoys encountered on trips to China. These new ways of thinking are often referred to by modern scholars as ‘Practical Learning’. But they now showed greater interest in their own land.

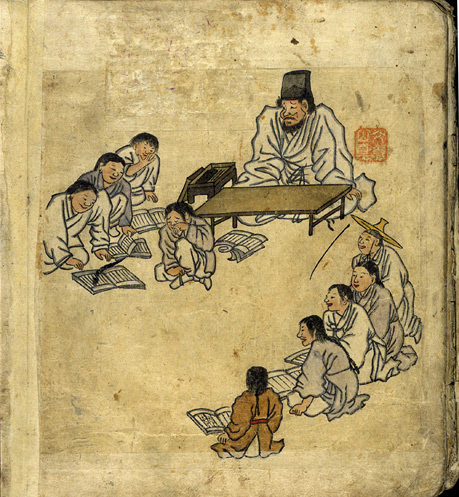

Scholars and artists in the 18th and early 19th centuries were increasingly focusing on their own society for inspiration. The literati wrote histories, compiled geographies, and drew maps of Korea. Artists such as Kim Hongdo depicted the everyday life of Koreans from all classes including farmers in the field, weavers, and people attending village markets or playing traditional sports. Other painters devoted themselves to capturing the scenic spots of the country, others to recording its beautiful women. There was also a blurring of non-elite and elite culture. Yangban continued to write poems and essays in classical Chinese, but they also read and often anonymously wrote popular novels. An example was The Story of Ch’unghyang, written in the 18th century and still well known among Koreans today. Both traditional genres of Chinese-style paintings and the local tradition of folk paintings, minhwa, flourished. A new type of performance, p’ansori, raised folk singing and storytelling to an art form, providing a unique Korean cultural expression which was appreciated by all social classes (Figure 4).

4. Chosǒn era sǒdang (village school), after Kim Hong-do, Album of Scenes from Daily Life, early 19th century.

Korea in the 18th century was a politically stable and prosperous Confucian kingdom. Life at the court in the 16th to 18th centuries was characterized by fierce competition for high positions in the state by rival factions. These were based on personal ties of loyalty as well as ideological differences. Those that lost out in power struggles were exiled to remote parts of the kingdom or even in some cases executed. However, in the 18th century under two able kings, Yǒngjo (r. 1724–76) and Chǒngjo (r. 1776–1800), a period of relative political stability was achieved. It was a time of prosperity and a cultural flowering.

After a terrible famine in 1693 to 1695, the population rebounded and probably peaked in the late 1700s at around thirteen million. Modest but significant improvements in agriculture—the increased use of double cropping and fertilizer, the use of more efficient ploughs, and the introduction of new food crops such as the potato and the sweet potato—increased output so that it kept up with population growth. Careful forest management prevented the problem of deforestation and ensured a supply of wood for construction and for the charcoal used to heat homes in the cold winters. Commerce, while still modest, expanded. There was an increased use of money, and farmers were entering the market economy by growing cash crops such as cotton and tobacco, the latter introduced in the 17th century. Women too seemed to be increasingly contributing to household incomes by making textiles at home for sale. In general, there were signs that family incomes were rising, if only modestly.

In the early 19th century there were some signs of trouble. Court politics was dominated by rival families who took turns placing weak kings on the throne. There was a drop in agricultural productivity, possibly due to environmental degradation, and even a decline in population. There was a serious rebellion in 1812 in the northern part of the country fuelled by resentment over regional discrimination and anger at excessive taxation. A rice riot shook Seoul in 1833. In 1862, the so-called Chinju Rebellion fuelled by corruption and high taxes spread across parts of southern Korea. A disturbing new religion, Christianity, gained a very small but growing number of followers. Another new religion called Tonghak (Eastern Learning) emerged in the 1860s. It combined ideas from Confucianism, Christianity, and folk beliefs and called for social reform. Yet none of these rose to the level where they posed a serious threat to the political and social order. It was only the intrusion of Western imperialism into East Asia in the mid-19th century that brought about a century of upheaval and gave birth to modern Korea.