Chapter 3

From kingdom to colony

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries Korea became exposed to the new Western-dominated world of modern imperialism. As a result, the political and social order was seriously challenged, and the very existence of the state was threatened. Koreans responded by carrying out reforms and rethinking their ideas about their society and its place in the world. Despite their efforts at meeting the challenges it faced, their country fell under direct foreign rule for the first time in its recorded history. These experiences were not unique to Koreans. For most of the people of Asia and Africa this period brought foreign, usually Western, domination and the disruption of the traditional patterns of life. However, with their limited connections to the world outside East Asia, Koreans were especially unprepared for the intrusion of modern imperialism.

Yet Korea had some strengths. It did not have ethnic or sectarian divides that characterized many other countries confronted by modern imperialism; elites and commoners, despite a large social gap, shared a common culture. It was ruled by a class of scholar-bureaucrats who had a strong sense of collective identity and attachment to a centralized state. Furthermore, Koreans had a long tradition of learning from other societies. These advantages were not enough to prevent Korea from becoming a Japanese colony. They do, however, help explain the speed with which some Koreans adjusted to the technological, institutional, and intellectual challenges of modernization, and the intense, passionate nationalism that emerged among the Korean people.

Korea’s changing place in the world

Until the late 19th century Korea’s contact with the wider world was limited. This was due to both the country’s geographic distance from the world’s major international exchange routes and the Chosǒn state’s policy of restricting contact with foreigners. Korea had never been entirely open to outsiders, but after the trauma of the Japanese and Manchu invasions and the shock of China falling to barbarians late Chosǒn so sealed itself off from the outside world that 19th-century Westerners labelled it the ‘Hermit Kingdom’. Chosǒn regulations prohibited Koreans from travelling abroad except on authorized embassies. Boats were restricted in size to prevent fishermen or merchants from sailing to another country. Foreigners were not permitted to enter the country, with two exceptions: the Japanese were allowed to trade at Pusan and Chinese missions came to Seoul. But the Japanese in Pusan were confined to a walled compound and the Chinese missions followed a prescribed route then entered the capital through a special gate into a walled compound. Unauthorized Koreans were prohibited from having contact with the visitors.

While these restrictions bring to mind comparisons with contemporary North Korea, Chosǒn’s isolation can be overdrawn. Koreans showed a lively curiosity about their neighbours and wrote many published accounts of their travels to China and Japan. Nor were they completely unaware of the West. Korean visitors to Beijing met with the Jesuit mission there, and Korean scholars read and commented on Chinese translations of Western science, medicine, and geography. They were often impressed with European skills at mathematics and astronomy. European clocks were imported as novelties. Yet few Westerners made it to Korea and no Korean is known to have travelled to Europe and returned. For most members of the elite, Europe was a distant society only on the periphery of their consciousness.

This began to change with the introduction of Christianity. In the late 18th century a handful of yangban converted after being exposed to Catholicism from their encounters with the Jesuit mission in Beijing. The Chosǒn king, worried that it would distract young scholars from their studies, ruled it a heresy in 1785. Soon after, when it became known that the pope had ruled that family rites and belief in Christianity were incompatible, becoming a Christian meant violating the basic ethical norms of Confucian society. A convert was executed in 1791 for failing to prepare a memorial tablet to his mother. In 1801, 300 converts were put to death. Alarm over the potential danger the new faith posed increased when one Korean Christian sent a letter to the pope requesting help in forcing the Korean king to allow religious freedom. In the 1830s, several French priests were smuggled into the country and their activities led to more executions in 1839. Despite this, the Christian community grew to perhaps 20,000 by the 1860s; many were yangban from out-of-power factions.

However, it was only in the mid-19th century that the West became a serious threat to Korea and its neighbours. Koreans watched while China suffered a humiliating defeat by the British in the Opium War, 1839–42. This was followed by the American opening of Japan to trade and diplomacy in 1854, a second European war with China that led to a brief Anglo-French occupation of Beijing in 1860, and Russia’s annexation of Chinese territory that same year. The last gave Russia a short border with Korea. As these events were unfolding, Chosǒn officials rebuffed several attempts by British, French, and Russian ships to open trade, reasserting that the country was not interested in commerce or relations with distant lands. In 1864, Taewǒn’gun, the father and regent of a young King Kojong, responded to more illegal entries of French priests into the country by executing them along with several thousand Korean Catholics. France retaliated to the killing of their citizens by sending a force of seven ships and 600 men to Korea in October 1866 but met fierce resistance and accomplished little. That same year, a heavily armed American merchant vessel, the General Sherman, sailed up the Taedong River to Pyongyang in an attempt to inaugurate trade. After it was told to leave, a confused altercation took place in which the ship was burned and its crew were killed. Five years later, in 1871, the United States, having learned about the missing ship’s fate, launched their own punitive expedition of five ships and 1,200 men that also attacked the fortifications on Kanghwa Island, killing hundreds of Korean defenders.

It was not Westerners but the Japanese who ‘opened’ Korea. In 1868, the shogunate was overthrown in a revolution labelled the ‘Meiji Restoration’. The new government, carrying out a modernization programme, used newly acquired modern naval vessels to threaten Korea. In 1876, King Kojong, who had assumed power from his hardline father, rather than risk conflict with his neighbour across the Strait, conceded to Japanese demands to establish formal diplomatic relations with the new Meiji government and to open select ports to Japanese merchants. In 1882, Seoul established relations with the United States and sent a mission there too. All this marked a new chapter in Korean history.

Late Chosǒn efforts at reforms

Koreans both inside and outside the government were quick to grasp the need to learn from outside powers and make major changes to survive and flourish in the new world they were facing. However, they confronted several serious problems. Koreans were not only suddenly flooded with new ideas about government, society, science, technology, and international affairs all at once, they had to find ways of applying them to their society. At the same time, they had to choose between different models and conflicting advice on how to carry out reforms. And they had to deal with the efforts of powerful neighbours to conquer or control them.

Soon after its ‘opening’ in 1876 the court sent officials to China to study the reforms being carried out there. Koreans had long regarded China as a centre for culture and learning so that was a natural model to learn from. Many were impressed with the Chinese ‘Self-Strengthening’ programme of cautiously borrowing Western technology, especially military technology, and engaging in Western-style diplomacy while maintaining their basic political institutions and values. Korean fact-finding missions also went to Japan, which offered a more radical response to imperialism—a thorough adaptation of Western legal, political, and educational institutions while maintaining their imperial house as a symbol of the country’s traditions. Some Koreans decided to learn directly from the West, primarily by going to the United States or learning from the American missionaries who were arriving in the country in the 1880s.

While searching for ways to navigate this new world, Koreans found themselves in the middle of three empires: the declining Chinese, the expanding Russian, and the rising Japanese. Each was seeking to gain some measure of control over Korea and was actively intervening in its affairs. China, struggling to keep its empire intact, sought to make Korea subordinate to Beijing and keep it out of the hands of another power. Russia, expanding in the Pacific region, looked at the peninsula to the south with an interest in its warm water ports and resources. The modernizing regime of Meiji Japan regarded control over Korea as a way of securing its periphery and providing a market for its goods.

The Chosǒn court in the early 1880s proceeded cautiously, creating some new institutions including a new body to conduct foreign relations patterned on those China had recently created. A group of young reformers who had been sent to Japan felt this was insufficient to deal with the crisis the country faced. Known as the Enlightenment Party they seized power in December 1884 with the intention of carrying out more sweeping governmental and social reforms on the model of the Meiji reformers in Japan.

The coup was short-lived. The Chinese, who had some troops stationed at their legation, intervened and the Enlightenment Party leaders were killed or fled the country.

The rash actions by more radical reformers and the Chinese intervention were a serious setback for Korea. This eliminated and discredited many of those who advocated a more accelerated pace of reform and empowered the Chinese, who exercised a considerable measure of control over Korea for the next decade. The Chinese stifled Korean efforts at reforms that might diminish Beijing’s influence over it. They made it difficult for Koreans to travel abroad, pressured the Chosǒn government to order students abroad to return home, and blocked efforts by Seoul to open embassies in Western countries. But the Chinese could not keep out foreign missionaries who opened schools and hospitals and exposed young Koreans to new ideas. Nor could they keep out the Japanese and Russians who opened businesses and indulged in political intrigue. China’s period of dominance came to an end in 1894 when the Tonghaks revolted. A panicky government in Seoul called on Chinese assistance but before troops could arrive Korean officials were able to negotiate with the Tonghaks, promising to look into their grievances. Although no longer needed the Chinese forces arrived anyway. Tokyo, concerned that China would consolidate its hold on the peninsula, sent its troops. This led to the Sino-Japanese War in which Japan’s modern army and navy inflicted punishing defeats on the Chinese and drove them out of Korea.

The Japanese victory eliminated China, in the competition to control Korea. Tokyo, now in control of events in Seoul, sponsored a reform-minded government that carried out a series of measures known as the Kabo Reforms. These eliminated yangban status, abolished slavery, established equality before the law, prohibited child marriage, allowed widows to remarry, and did away with the civil service exams. A new Western calendar was adopted and the tributary status with China officially came to an end. The Kabo Reforms were enthusiastically enacted by Korean reformers who had been sidelined or exiled for the past decade, including surviving members of the Enlightenment Party. But the reformers, no matter how sincere, were viewed by many as instruments of Japan which was tightening its grip over the country. Anti-Japanese feeling was inflamed when Japanese thugs, acting under the direction of Tokyo’s minister in Korea, murdered the staunchly anti-Japanese Queen Min, covered her body in kerosene, and burnt it.

Some Koreans sought the help of Russia in freeing the government from Japanese control. St Petersburg, eager to extend its influence in the peninsula, obliged. In early 1896, a pro-Russian faction at court spirited King Kojong out of the palace, past the watchful eyes of the Japanese, and off to the Russian legation. The king ruled from the Russian legation protected by Cossacks. This pathetic state of affairs encouraged a group of Korean progressives to form the Independence Club led by the American-educated Yun Ch’iho, and later joined by Sǒ Chaep’il, an 1884 coup leader who returned from exile in the USA. The Club called for modern representative government, and an independent foreign policy. Under its influence the country was renamed the Great Korean Empire; King Kojong became Emperor Kojong. This was a final break with the Sino-centric tributary system, and symbolically placed Korea on equal footing with its imperial neighbours. In another break with tradition and to emphasize Korea’s cultural independence from its neighbours its newspaper was printed in Hangul, not in Chinese characters. However, before the Independence Club could carry out further reforms, Emperor Kojong and his conservative advisers, fearing it was acquiring too much power, had it banned; its leaders were arrested or, like Sǒ, fled abroad.

From empire to colony

Despite its new imperial status Korea, or the Great Korean Empire as it was now called, was a weak, politically divided state led by a vacillating, indecisive king now titled emperor. His government had to deal with the imperial ambitions of Japan and Russia, both keen on securing control over the country and denying it to the other. Some Koreans looked to the United States to balance the power of Japan and Russia. But despite a strong American missionary presence, Washington showed little interest in the country. Tokyo made a secret offer to St Petersburg to accept Japanese control over Korea in exchange for Japanese recognition of Russian interest in Manchuria. But this was rejected by the Tsarist government. Then, in 1904, Japanese forces carried out a surprise attack on the Russians in Manchuria, launching the Russo-Japanese War. When Japan emerged victorious in 1905, Russia conceded Korea and much of Manchuria as a Japanese sphere of influence. President Theodore Roosevelt, who brokered the peace settlement, tacitly gave Tokyo a free hand in Korea in return for its recognition of the American presence in the Philippines. Britain too, which had formed an alliance with Japan in 1902, recognized Tokyo’s paramount interests in the peninsula. Consequently, with the blessings of the great powers, Japan declared Korea a protectorate in 1905. Western states closed their embassies and Korea became all but in name a Japanese possession. Korea sent representatives to a peace conference in The Hague in 1907 to protest Japanese violation of its sovereignty, but the outside world showed little concern for its plight.

For five years, Korea was nominally independent but in reality power shifted from the Korean monarch and prime minister to a Japanese resident-general, and from the Korean cabinet ministers to their Japanese advisers. In 1907, the army was disbanded, and when Kojong began to act too independently he was forced to abdicate in favour of his mentally incompetent and easily manipulated son Sunjong. In 1910, Korea was formally annexed. Some Koreans, viewing the Japanese as agents of progress, supported the annexation of their country, some resigned themselves to the inevitable, some violently resisted. The last formed ‘righteous armies’ which carried out a war of resistance from 1907 to 1910. About 10,000 were killed fighting the vastly superior Japanese forces.

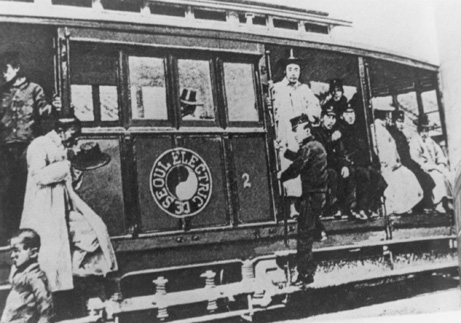

It is easy to look back at these last years of Korea as a sovereign country and view it as an ineffective, pathetic, and even hopelessly backward state. Yet the brief Great Korean Empire enacted legal reforms, established the basis for a modern education system, carried out a systematic land survey, and signed contracts with foreign investors to construct modern infrastructure. In 1899, for instance, the first railway opened linking Seoul with the port of Inchon (Inch’ǒn) and the first electric street cars began operation in the capital (Figure 5). Many individual Koreans began embracing change: starting newspapers, establishing modern schools, opening businesses. A small number of intellectuals absorbed Western ideas, reading Western political, economic, and scientific works, usually in Japanese translations.

5. Seoul street car, 1899.

Many educated Koreans, using the new media such as newspapers, began to re-examine what it meant to be Korean and the place of Korea in the world. They began to place their society in the context of world not just East Asian history. They adopted the modern idea that history was a linear march of progress, and they feared that their country had fallen behind. Many Korean intellectuals felt their task was to direct Korea’s efforts to modernize and strengthen itself if it was to survive.

Korean writers began to define themselves as members of a nation in the modern sense. Early manifestations of modern nationalism include the Independence Club formed in 1896, and the work of Sin Ch’aeho, who wrote a work on Korean history in 1905 as the story of a nation. But this new identity competed with or was combined with other new categories for labelling themselves. As a result of their encounter with Western ideas they began identifying as ‘Easterners’ and as Asians. Some embraced Pan-Asianism, an idea developed by some Japanese thinkers that all the peoples of the Pacific Rim of Asia should cooperate in challenging the dominance of the West, and that Japan should lead them in this effort. Pan-Asianism was influenced by social Darwinism, especially its German form that emphasized the history as a struggle for survival among the races. Other Koreans incorporated social Darwinism in their ideas of nationalism—history as a struggle among nations for survival.

Modernization under colonial rule

Korea’s colonial experience was in many ways typical of Asian and African peoples in the age of imperialism. Japan, like other colonial powers, directed the development of Korea for its own benefit not for that of Koreans. Koreans were treated as inferior subjects, their traditions were often denigrated, and they were excluded from positions of authority. It was a humiliating experience. Nonetheless, some embraced the new opportunities that were made available and accepted the claim by the Japanese that they were bringing progress and enlightenment. Many Koreans were active agents, not just passive victims, of the colonial administration, serving as police and holding minor positions in the bureaucracy. Some became admirers of Japanese culture and took pride in being part of the great, rising Japanese Empire. Others resisted, some violently, some more passively; several thousand became exiles and plotted the overthrow of colonial rule from abroad.

In other ways Korea’s colonial experience was unusual. Unlike many colonial subjects, such as the peoples of Indochina, India, or West Africa who were ruled by a distant and alien nation, Koreans were governed by a familiar, culturally related neighbour. Although warrior-dominated Japan had a very different social system from Korea, it shared traditions of Buddhism, Confucianism, and a long history of borrowing from China. Furthermore, Korea’s colonial experience was unusual in its intensive and intrusive nature. Europeans often ruled indirectly working with local African chiefs, or rajas or emirs, but in Korea all authority was concentrated in the centralized Japanese administration. By the 1930s about a quarter of a million Japanese civilian, military, and police personnel were employed in Korea. This was about the same as the number of British in India, which had more than fifteen times the population, ten times as many as the French in Vietnam, a colony with a similar population to Korea. While an Indian or African peasant might only rarely encounter a British or French colonial official, ordinary Koreans encountered them every day—the Japanese schoolteacher, the postal clerk, the village policeman. The police had the power to judge and sentence for minor offences, to collect taxes, to oversee local irrigation works, even to inspect businesses and homes to see that health and other government regulations were being enforced. It was a top–down administration with all officials, police, and military directly answerable to the governor-general, always a Japanese military man appointed by Tokyo. Koreans served mainly in the lower ranks of the bureaucracy and were excluded from any meaningful participation in decision-making.

Korea’s geopolitical situation also made its colonial experience different. The Japanese saw the peninsula as occupying a strategic position—first as protecting the homeland from foreign invasion, second as a springboard for advancing into Manchuria and the Chinese mainland. It therefore carried on infrastructure and industrial development to serve these purposes. Tokyo, for example, built an extensive railway system with nearly as many miles of track as in all of China; its primary purpose was to transport troops from Japan to Manchuria as well as Korean goods to ports. After 1930, it developed the mineral-rich north as a major industrial base, leaving Korea with a more developed infrastructure and more industrial plants than most other colonies.

Another peculiar feature of Japan’s rule was its assimilationist policy. Other colonial powers, especially the French, had sought to promote cultural integration among elements of the educated elite, but Japan conducted a massive, if inconsistent, attempt to forcibly assimilate the entire population into Japanese culture. Officially the policy was based on the fiction that the two peoples were originally one but had become separated. The Japanese had progressed while the Koreans had stagnated. It was now the duty of Tokyo to reunite with their backward Korean relatives and absorb them into Japanese society. But this policy, which meant trying to erase Korea’s culture and identity, was contradicted by the practices of carefully segregating Koreans and Japanese, building different schools, dividing cities into separate neighbourhoods etc., and treating Koreans as an inferior people with a subordinate role in the empire.

Colonial modernity

Before 1910, Koreans began the process of modernization; after 1910 the process accelerated but it was directed by the Japanese colonial authority primarily to serve Japanese interest. Nonetheless, many Koreans benefited economically. A new middle class emerged: teachers, doctors, accountants, businessmen, bankers, and civil servants in the colonial bureaucracy who were connected to the modern world. They wore Western-style clothes, read newspapers, magazines, and foreign books in translation. They sent their children to modern schools where the curriculum included science and maths as well as civics, history, and literature. This new middle class included a group of modern entrepreneurs. The old stigma against commerce was diminishing and many educated Koreans entered businesses of all kinds. Some operated rice mills, textile plants, trucking companies, and banks. This small Korean business class worked closely with their Japanese counterparts, but they had their own separate chamber of commerce in Seoul. Some of these such as Kim Sǒngsu and his brother Kim Yǒnsu, owners of the Kyǒngbang Textile Company, were of yangban background, a break with the traditional aristocratic avoidance of commerce. Others such as such as Pak Hǔngsik, owner of retail stores and the richest man in colonial Korea, came from a commoner family.

Even among this new middle class, however, men’s attitudes towards women changed slowly and few women appeared in public life. Yet for women things were changing too. Many left home to take jobs in factories where they made up a substantial portion of the workforce. And women were getting educated, although the purpose of educating women was not to prepare them for professional life, but for roles as ‘wise mothers, good wives’, who could better supervise the education of their children. A few women, however, broke from even this changed role, becoming writers, educators, artists, and active in political movements. One of these, Kim Wǒnju, published Sin Yǒsǒng (New Woman), a 1920s magazine aimed at the modern woman. The title ‘New Woman’ came from the popular term for modern Korean women who entered the professions, became politically active, and rebelled against the limitations that society had placed on them—women such as Pak Kyǒngwǒn, the first Korean woman aviator.

Yet most Koreans benefited little from this colonial modernization. Korean workers earned only a third of the wages of their Japanese counterparts and were seldom allowed to rise to management levels. Labour strikes and other forms of unrest were common until repressive measures in the 1930s made any form of collective action extremely difficult. Education expanded but it was designed to meet the requirements for educated labour. Few upper-level schools were built. In fact, the pace of educational development was so slow that non-accredited private schools grew rapidly in the 1920s–1930s to meet demand.

Despite the growth of industry and urbanization, Korea remained a rural society. Three-quarters of the population were peasants, and for the most part this group experienced the greatest hardship from colonial modernization. Landownership declined, and most peasants became tenant farmers. When the Japanese carried out systematic land surveys many peasants lost land because they could not prove ownership, which was often based on custom. As a result, most of the land fell into the hands of rich yangban who took advantage of their knowledge of law and of government regulations. Eventually, about 2 per cent of rich families possessed over half the land. Most farmers either owned no land or not enough to support a family. To survive they had to rent land from a big landowner or work in his fields. Small farmers were required to cultivate some crops for the market and then found that the increasing commercialization of agriculture subjected them to sharp market fluctuations. They frequently accumulated high levels of debt. Population growth also put pressure on the land. Among the worst-off farmers were those who moved into the mountain forests, where they squatted on public land. They would burn trees and bushes, sow and harvest a crop, then move on to another field, barely eking out a precarious existence. This contributed to the deforestation of the country as traditional customs that protected the woodlands broke down. By the end of colonial rule, the barren mountainsides of the country came to symbolize to some the rape of the country under foreign occupation.

Of all the hardships experienced by rural Koreans few were recalled with greater bitterness than the disappearance of rice from their tables. Rice production went up under colonial rule; however, this was to supply the Japanese homeland. Cheap millet, contemptuously regarded as ‘coarse grain’, was imported from Manchuria for Koreans while the rice they grew went to the Japanese. By the end of the colonial period, Korea had become a land where the majority of the population were farmers who owned no land or not enough to support themselves, who were burdened with high rents, high land taxes, and could not even eat the rice they grew. This resulted in peasant unrest that would come out in the open when colonial rule ended in 1945.

The birth of modern Korean nationalism

Nationalism emerged as a powerful emotional force among the people during colonial rule. At the start of colonial rule in 1910, the concepts of nation and nation-state were still new ones largely confined to small circles of thinkers and people who had been educated abroad or in Western-run mission schools. By 1945 most Koreans had come to see themselves as members of a Korean nation. Modern nationalist sentiment and nationalist movements emerged in almost all of the colonies during the first half of the 20th century in the form of anticolonialism. It often served as a means of integrating diverse ethnic, religious, and other groups into a single community based on the colonial territory. However, Korea already had a long experience as a territorially stable, centralized state with an ethnically and culturally homogeneous population. For that reason nationalism was able to quickly become a popular and powerful force.

The first great outburst of Korean nationalism was the March First Movement of 1919. At the end of the First World War President Wilson declared the principle of national self-determination. This excited many victims of imperialism across the world. Koreans were among the first to be animated by this promising turn of international events. In late February representatives of various Protestant, Chǒndogyo (as the Tonghak religion was renamed), and Buddhist groups decided to issue a declaration of independence, as a kind of peaceful protest statement in a park in Seoul. What happened instead was a largely spontaneous mass protest involving hundreds of thousands of Koreans in every province and city in Korea. Although mostly peaceful it was violently suppressed by the Japanese; several thousand were killed, thousands arrested. Taken by surprise, an embarrassed Japanese government changed its colonial policy toward a more liberal one in the 1920s. Upon annexing Korea in 1910, the colonial authorities had closed most Korean newspapers and publications, as well as many private schools. But in the wake of the March First Movement they allowed newspapers and journals in the Korean language, as well as a number of private organizations that promoted Korean culture. It was in this limited space that a great flowering of Korean literature, political thought, and historical studies flourished.

The Korean nationalist movement, however, soon became ideologically divided. Moderates sought a gradual approach toward independence. These gradualists, such as the influential writer Yi Kwangsu, had a free and independent Korea as their aim but saw it as a long-term project. Korea had to first improve itself by working within the boundaries permitted by the Japanese colonial administration to modernize the country. A major task was to educate the still ‘backward’ people. Only when the people achieved a sufficient level of maturity and ‘modernity’ would Korea be ready to join the ranks of sovereign states. Moderates, including much of the new middle class of businessmen, educators, writers, and journalists, established schools, newspapers, and self-improvement societies that they believed would lead the ignorant masses into the modern world. Thus, they were able to persuade themselves that they were forwarding the independence movement by cooperating with the colonial occupiers. In seeking ways to create a modern society they looked for models not just in Japan but in the Western countries of Europe and America. This was especially true of the Christians, a group disproportionally represented among moderate nationalists. With their ties to Western missions and unease with the Japanese imperial cult they were especially open to Western concepts of modernity.

Many Korean nationalists turned to more radical paths to achieve liberation and to establish Korea as a member of the international community of modern sovereign states. They took ideas from many sources, such as anarchism, but none was as influential as communism. At first few Koreans had any awareness of communism. This changed with the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Lenin’s denunciation of imperialism, and the offers of the new Bolshevik regime in Russia to provide assistance to colonial peoples in the struggle to free themselves from foreign rule. When Lenin called an international conference of the Toilers of the East in Moscow in 1922, Koreans were the largest group to attend. In a complex, confusing world Marxism-Leninism had much to offer. It provided an explanation for the country’s weakness, its poverty, and its victimization at the hands of the Japanese. It was an all-embracing philosophy, which like Neo-Confucianism presented a clear path to a virtuous, harmonious, prosperous society. In fact, Korean Marxists were very much like their Neo-Confucian ancestors, coming back from abroad with a prescription to cure society’s ills and lead it to a bright future. Young Koreans formed several Marxist ‘study clubs’. In 1925 they made four attempts to organize a Korean Communist Party; each time the Japanese police quickly arrested its members. Nonetheless, an underground domestic communist movement continued.

Not all radical nationalists fully adhered to or understood orthodox Marxism-Leninism, but they shared the scorn for the elitist views of the moderate nationalists whom they saw as self-serving Japanese collaborators. All radical nationalists, whether or not Marxist, viewed the struggle for independence as inseparable from the internal struggle to liberate the people from exploitation by the elite. Some of them formed labour and peasant organizations, others confined their activities to writing and waiting for an opportune time to bring about liberation of the nation and its people. Korean communists saw themselves as part of an international movement and in theory identified with the global struggle of the working class. Yet the Marxist emphasis on class identity over nation never replaced the passionate nationalism of its Korean adherents.

Many Korean nationalists were based abroad. However, rather than a unified movement they were divided by ideology, disagreements on tactics, and by geography. Most independence movements among Asians and Africans during the heyday of colonialism had an important overseas base of operation: London, Paris, Switzerland, New York, etc. Korean exiles were scattered all over the globe. Some worked in Tokyo before the repression of the 1930s made that no longer viable. Others were in Shanghai, Manchuria, western China, Siberia, Hawaii, and the US mainland. The efforts of these globally dispersed groups were largely uncoordinated. In 1919, they tried to combine their efforts and formed the Korean Provisional Government in Shanghai. Its first president was the American-based nationalist leader Syngman Rhee (Yi Sǔngman). This organization, however, proved too ideologically diverse to be effective. Some Korean exiles carried out terrorist attacks against the Japanese; in one they narrowly missed assassinating Japanese Emperor Hirohito. During the Second World War exiles in China fought with the Chinese. Kim Ku led a Korean Restoration Army with several thousand fighters that fought with the Kuomindang regime based on Chungking. A larger number served with the Chinese Communist Party under its leader Mao Zedong. These were organized in 1942 as the Korean Voluntary Army.

Even before the war, several thousand Koreans were fighting the Japanese in the mountains of Manchuria along the northern border of Korea. Drawn from the hundreds of thousands of Koreans who had emigrated to Manchuria, they served under the Chinese Communist Party. One of these young Korean guerrilla fighters was Kim Sǒngju, whose father had settled in Manchuria from the Pyongyang area when he was 9 years old. Kim joined the Chinese Communist resistance to the Japanese sometime around the age of 20, changing his name to Kim Il Sung (Kim Ilsǒng). At the young age of 25 he led a small guerrilla raid on the border city of Poch’ǒnbo, briefly capturing it from the Japanese. This raid in June 1937 made Kim Il Sung modestly famous, since it was widely reported in the Korean language press. Overall, these guerrilla raids were little more than a nuisance to the well-organized and equipped Japanese military. Tokyo destroyed most of these Korean and Chinese guerrillas in Manchuria in a 1939–40 anti-insurgency campaign. The survivors, including Kim Il Sung, fled across the Soviet border.

Wartime totalitarianism

Korea’s colonial experience took an increasingly authoritative and coercive turn in the 1930s. As the Great Depression engulfed much of the world, and the international trading system was replaced by a rise in protectionist policies, the Japanese government in Tokyo shifted in an increasingly militaristic, ultra-nationalist direction. In 1931, the Japanese began a takeover of Manchuria, creating a puppet state in the huge, resource-rich region. Six years later the Japanese launched a large-scale invasion of China, capturing its capital Nanjing in 1938. After the start of the war with China in 1937, Japan moved in an increasingly totalitarian direction at home and in Korea.

As the Japanese government moved in a more ultra-nationalist, expansionary direction it began insisting that Koreans actively support the goals of the empire. From 1935 all Koreans were required to worship at Shinto shrines. From 1937 they were required to recite the Oath of Subjects of the Imperial Nation. Schoolchildren began their day by bowing in the direction of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. The colonial government closed Korean organizations, replacing them with large-scale state-sponsored ones. Writers belonged to the writers’ association designed to direct their efforts toward wartime propaganda, young people to the Korean Federation of Youth Organizations. In 1940, the entire country was organized into 350,000 Neighbourhood Patriotic Organizations, each with ten households. These new organizations were used by the state to collect contributions, carry out rationing, and organize people for ‘volunteer’ labour. Through them almost everyone was enlisted for tasks such as building airstrips and collecting useful materials for war production.

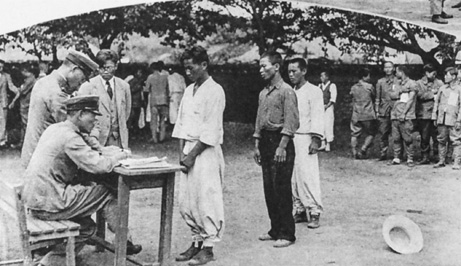

By 1940, the colony was taking on the character of a totalitarian state where all activity was directed towards the goals of the state. When the war expanded in late 1941 from a conflict with China to one with the United States and the British Empire, hundreds of thousands of Koreans were conscripted to work in Japan. School terms were shortened so that students could do voluntary labour and many young people were among those sent to Japan as labourers. In fact, by 1945 a sizeable portion of the total labour force in Japan was Korean (Figure 6). A most tragic development that remains a sore point between Korea and Japan today was the use of up to 200,000 young Korean women as ‘Comfort Women’. Recruited under false pretences they were forced to serve as prostitutes for Japanese troops. Returning home in disgrace, many had to carry the shame for their entire lives.

6. Recruitment of Korean workers for Japan, Kyǒngsang Province, c.1940.

The mass mobilization of the people for the war effort was accompanied by an attempt at forced assimilation. As part of the process of making what one official slogan referred to as ‘Korea and Japan—One Body’, limitations were placed on the use of Korean. From the late 1930s the use of the Korean language in schools was restricted further and further until students could be punished for speaking it. Korean-language newspapers were shut down and virtually all publications in Korean ceased. In 1940, Koreans were required to change their names to Japanese ones. This ‘loss of names’ was especially traumatic in Korean society where the veneration of ancestors and maintaining family lines was so important. It was more than a loss of identity, it was a betrayal of one’s ancestors.

Ultimately, Tokyo’s efforts at assimilation were not very successful. A few Koreans accepted the reality of being part of the Japanese Empire and sought to adopt Japanese culture. Yet no matter how hard they tried, Koreans were not accepted by Japanese as one of them. Nor did they mix socially. Belonging to an insular, racially exclusive society, the Japanese kept apart from Koreans and intermarriage was rare. Rather than creating harmony and unity between the two peoples, colonial policies and attitudes did quite the opposite; they contributed to the emergence of a passionate Korean nationalist sentiment.