Chapter 5

Competing states, diverging societies

By 1953 almost all Koreans had accepted that they belonged to a single nation united by blood, culture, history, and destiny. However, the end of the Korean War left them divided into two states. Each state shared the same goal of creating a prosperous, modern, unified Korean nation-state that would be politically autonomous and internationally respected. The leadership of each saw the division as temporary and themselves and the state they governed as the true representative of the aspirations of the Korean people, and the legitimate successor to the pre-colonial state. Each state saw itself as in competition with the other to demonstrate that it deserved to represent the entire Korean nation and to be in the better position to reunify the country. Yet while sharing many of the same goals they followed very different paths to reach them and thus they became ever more divergent societies.

At first North Korea appeared to be the more successful of the two states in building a modern, militarily strong, self-reliant industrial state. It rapidly recovered from the Korean War and in two decades became the most urbanized and industrialized country in Asia after Japan. South Korea after an unpromising start characterized by political corruption and instability, and seemingly intractable poverty, entered a period of high economic growth after 1961, transforming itself into an industrial nation under an authoritarian military government. South Korea’s trajectory of development was the reverse of North Korea’s. Its economic development was floundering when the North was roaring ahead, then it began speeding up when the North was slowing down. In the 1980s the South began transition into a democratic society as the totalitarian leadership of the North was evolving into a family-run state; and the South became more globally engaged as the North was becoming internationally isolated.

North Korea’s path of modernization and rapid development

For at least the first decade after the Korean War, the DPRK was the more successful of the two Koreas in the competition to establish itself as the legitimate leader of all the Korean nation. Kim Il Sung was able to consolidate his control over the state and the state’s control over society. At the same time his regime carried out a rapid economic modernization, building up an industrial base, expanding education, improving health care, all the while achieving a high degree of autonomy from its patrons: the Soviet Union and China. By any measure it was an impressive achievement.

Within a month of the 27 July 1953 ceasefire Kim and his former Manchurian guerrilla partisans began to eliminate their rivals in the leadership of the ruling Korean Workers’ Party. In a series of Stalinist show trials the leaders of the domestic communists admitted to being agents of the American imperialists and their southern Korean collaborators. All were promptly executed except the most prominent member, Pak Hǒnyǒng. He was dropped from the Party leadership and quietly arrested and executed two years later. Another major shake-up took place in 1956 when, emboldened by Khrushchev’s denouncing the crimes of Stalin and his cult of personality at a secret session of the Soviet Communist Party in February that year, Pak Ch’angok, a prominent Soviet-Korean, and Ch’oe Ch’angik, a leader of the Yenan faction, challenged Kim Il Sung. The challenge failed; Kim removed them from power. In 1957, Kim Il Sung carried out a massive reorganization of the Korean Workers’ Party. The result was a three-year purge in which tens of thousands of members whose loyalty to the regime was considered suspect were expelled from the Korean Workers’ Party and arrested. Not only Pak and Ch’oe but almost all leaders of the Party who were not from the ex-Manchurian guerrilla faction were removed from office, imprisoned, and in many cases executed.

This massive purge, which resembled the Great Purges Stalin carried out in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, went much further than eliminating potential rivals in the Party. The regime divided the entire population of Korea into three categories: loyal, wavering, and hostile. These were based not only on individual actions but on family backgrounds. Anyone whose family had served in the Japanese colonial administration, been a landlord, owned a business, or had relatives in the South was classified as hostile—up to a third of the population. About 20 per cent, mainly those with untarnished worker or peasant background and who had demonstrated their support of the regime, were placed in the loyal group and the rest in the wavering group. These categories became permanent and inherited. State decrees prevented those from hostile backgrounds from living in the capital or near the border with the ROK. Many were relocated to the remote and impoverished north-east.

Later in the late 1960s these three groupings were subdivided further into sǒngbun, a series of graded categories from the most to least loyal. These were also based on family as well as personal background. Those who fought in the mountains with Kim Il Sung or were related to him were at the very top. Thus, North Korea created a system of inherited social ranks, resembling that of pre-modern dynastic Korea but even more elaborate. Family backgrounds were a factor in determining status in other communist societies, but the DPRK’s elaborate and rigid sǒngbun system was without precedent in the modern world.

By the early 1960s, Kim Il Sung and his Manchurian guerrilla companions were in total control. There was a further smaller-scale purge in 1967. Thereafter, the entire leadership of North Korea consisted of this group, including their family members and their patrons. They were mostly Koreans with only a modest formal education, who grew up in Manchuria not in Korea, men with little exposure to the larger world. They were among the least educated, least cosmopolitan group to dominate any modern society.

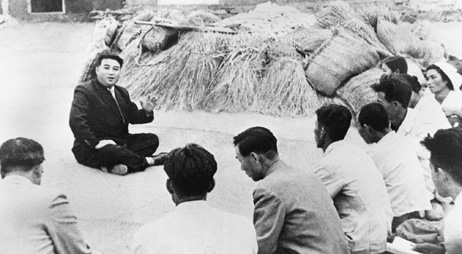

Simultaneously, the Kim Il Sung regime focused on building a modern industrial economy. From 1953 to 1956, with assistance from their Soviet, Eastern European, and to a lesser extent Chinese allies, the North Koreans rebuilt their cities, their industrial plants, and their infrastructure. Mass mobilization campaigns put almost every available citizen to work for this effort with impressive results. At the same time the state consolidated private farms into state-owned ‘cooperatives’ in which peasants became salaried employees working the land they once owned. This effort was largely completed by 1957. So North Korean farmers within a decade of becoming landowners again became agricultural labourers, this time for the state (Figure 8). By then the government had taken over the last small private businesses, completing the socialization of the economy.

8. Kim Il Sung talking with farmers from Kangsǒ County, October 1945.

In 1957, the regime launched a five-year plan to expand industrial development. Initially modelled on the Soviet five-year plans, after Mao began his Great Leap Forward in 1958 Kim modified the plan to resemble it. Following the Chinese leader, he raised his production goals, consolidated the collective farms into larger, more self-sufficient units, and sent officials to the countryside to learn from the people. Like Mao he hoped to achieve heroic advances in modernization by organizing the common people and instilling revolutionary fervour in them. Unlike Mao, however, he began to modify his plans when they proved unrealistic and avoided the disaster that China’s Great Leap Forward brought upon the Chinese people. This was followed by a more achievable but still ambitious Seven-Year Plan for 1961–7. In carrying out his development plans, Kim, like Stalin, emphasized heavy industry over consumer goods. Heavy industry would make his country less reliant on capital goods from his patrons and form the basis for domestic arms production. Thus, industrialization was inseparable from the goal of achieving as much autonomy as possible and becoming a militarily strong state, capable of reunifying the country.

The regime’s plans were too ambitious to be achieved. Nonetheless North Korea continued to maintain high economic growth rates into the early 1970s. By that time it was the most urbanized and industrialized country in Asia after Japan. It had reached a level of urbanization and general literacy achieved by China only after 2010. More importantly, for the leadership, it was outperforming its rival in the south. While living standards were low, life improved for most North Koreans. Education expanded and adult literacy programmes brought literacy to most of the adult population. The entire population had access to basic health care. Massive housing projects moved the urban population into modern apartments, small and crowded but with indoor plumbing and electricity. The latter reached rural homes as well.

North Korea also achieved a greater degree of political autonomy from its patrons. Kim declined membership in the Comecon, the Soviet Union’s economic alliance, and avoided getting too close to China while receiving aid from both Moscow and Beijing. The Sino-Soviet split provided Kim Il Sung with an opportunity to play off the two communist giants, each of which saw strategic advantages in maintaining ties with the DPRK. He briefly abandoned the ‘equal distance’ approach in mid-1963 when he openly sided with China. Moscow retaliated by cutting aid, which was a blow to Korea’s economy. After 1965 relationships were patched up and Pyongyang generally maintained good relations with both Moscow and Beijing for the next three decades. The Kim Il Sung regime had not only gained almost complete control of its people, eliminated possible internal rivals, and come a long way toward building a modern industrial society, it had also achieved mastery over its own affairs without outside interference. In a land whose fate in the previous century had been, to a considerable extent, in the hands of outside powers, the last was a notable achievement.

South Korea: uncertain state and then ‘economic miracle’

During the first decade after the Korean War, South Korea under Syngman Rhee appeared to be losing the competition for modernization and development. His regime was characterized by authoritarian rule, pervasive corruption, and only modest recovery and growth despite massive US aid. Yet the Rhee administration had some achievements. Land reform was finally carried out, education was enormously expanded, and thousands of South Koreans went abroad mostly to the United States for advanced studies, forming a pool of well-trained technocrats when they returned. Rhee was ousted in a student-led protest over the blatantly fraudulent elections of 1960 (Figure 9). There was a short-lived experiment with a parliamentary democracy and then in May of 1961 a military coup led by General Park Chung Hee (Pak Chǒnghǔi). Park and the mostly younger officers who planned the coup were frustrated by what they saw as the corruption and incompetence of the civilian government. They were humiliated at the country’s dependence on the United States, which provided over half the funds for the state, and whose 60,000 troops in South Korea assured its security. Most of all, they were alarmed at the apparent success of the DPRK in developing a modern, industrial, and more self-reliant state while their Korea was mired in economic stagnation and reduced to dependency on a foreign power. They felt a real fear that the ROK was losing its sense of legitimacy among many of its own people, a fear stoked by student demonstrations that seemed receptive to Pyongyang’s overtures.

9. Jubilant Korean students swarm over a tank in Seoul, after a civilian rebellion toppled Syngman Rhee from the presidency, April 1960.

The new military-led government of South Korea followed many of the same patterns of development as the North. The government sought to gain more control over society and introduce more discipline and regimentation. It created an elaborate secret police force, the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA), that maintained a vast network of informants. Citizens were mobilized in campaigns of various sorts, although they were not forced to do uncompensated ‘voluntary’ labour on public projects. There was a greater emphasis on military readiness and military training was introduced into the schools. The main focus of the new regime was on economic development and this too followed the DPRK in many respects. It nationalized the banks and arrested many of the country’s leading businessmen in anti-corruption drives. In 1962, it implemented the First Five-Year Development Plan with well-defined industrial and infrastructural targets.

But the Park government also deviated from the development path of the North in significant ways. After forcing most of the country’s leading entrepreneurs to pay hefty fines it enlisted them in the effort at pulling the country out of poverty. Lee Byung Chull (Yi Pyǒngch’ǒl), the country’s richest businessman, was made the head of an economic advisory council. The state set the goals, then channelled loans on favourable terms to private businesses that competed to complete them. The state also assisted companies with tax breaks, export assistance, favourable rates on state-owned railroads, utilities, and in other ways. But state help was based on the performance of private companies. Those like Hyundai or Ssangyong that proved efficient were favoured over their less effective competitors. These favoured companies grew into giant conglomerates known as chaebǒls. To promote efficiency Park made sure there were at least two competing firms in each sector. His formula—combining private enterprise with state planning and direction—proved highly successful.

South Korea’s development also differed from that of the DPRK by creating an export-oriented economy. Park, like Kim, hoped to eventually develop an industrial base that could support an arms industry and free itself from dependency on its patron, the United States. Like Kim, Park spoke of the need for self-reliance. However, lacking technical know-how and capital for heavy industry he opted to focus on consumer industries for the export market. The first five-year plan emphasized textiles, footwear, wigs, and other low-tech, labour-intensive industries for overseas markets. The state also encouraged foreign investment especially from the United States and Japan. Allowing the Japanese to invest heavily in the economy was highly controversial. When Park signed a peace treaty and established full diplomatic relations with Japan in 1965 it ignited mass protest demonstrations so large that they posed a threat to his regime. These mostly student-led protests were based on real fears that Korea would once again become an economic appendage of its former colonial master. Yet the regime’s decision to override nationalist sentiment meant that Japanese investment flowed into the country at a time when rising labour costs in Japan made transferring production to its next-door neighbour a practical move. South Korea proved to be an attractive place not only for Japanese but also for American and Western European firms. Park offered them a variety of tax incentives, a low-wage but educated workforce, and state assurances that it would crack down on any labour unrest.

South Korea also differed from North Korea in lacking the degree of political autonomy North Korea achieved in the 1950s. It remained dependent on Washington, which held a partial veto over its policies. American pressure, for example, forced Park to return the government to civilian rule. Taking off his military uniform he ran for and was elected as president in 1963. And although his regime maintained much of the character of an authoritarian police state there were opposition parties, a moderately free press, and some tolerance of the frequent anti-government student demonstrations. This along with independent Christian churches, an array of private organizations, and interest groups made South Korea a more pluralistic society, one in which the state dominated but did not totally control.

Under the Park regime the ROK never achieved the level of freedom from outside control that the DPRK did. Yet South Korea began to economically outperform its northern rival. By the end of the 1960s the economy was growing fast, probably faster than that of the North, and living standards were higher. Sometime, at least by the mid-1970s, if not earlier, South Korea had surpassed the North by every measure of economic strength and well-being of its citizens—education, nutrition, housing, health, and GDP per capita.

The endless conflict

The great issue of national reunification was left unresolved by the Korean War. Neither North nor South saw a division as anything but a temporary situation. South Korea’s position at first was mainly defensive. It sought to be prepared if the North attempted to invade again by building up its military and through its alliance with the United States which kept troops along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and in bases throughout the ROK. The USA supplied the ROK forces with equipment and training. By the early 1960s, with 600,000 in its forces plus reserve units South Korea had one of the world’s larger militaries. North Korea’s during the first decade after 1953 concentrated the DPRK’s energies on recovery, the consolidation of the regime, and economic development. But these were done with reunification in mind. Industrial development was aimed at better preparing the country for a resumption of the conflict and at impressing the people of the South that it represented the path to a future unified nation-state.

North Korea began to divert more of its resources to military preparation after 1962 when it began its ‘equal emphasis’ policy of simultaneously expanding economic and military development. Most of the adult population was given some sort of military training; a significant proportion were on active reserve. Compulsory military training was lengthened until it was often more than ten years. So many men were in the armed forces that eventually the DPRK had a larger military than the ROK despite having only half its population. By the 1970s, it had the largest percentage of its citizenry in active service of any state in the world. The country was fortified, with many miles of underground tunnels designed to withstand American and South Korean bombing. Military production was speeded up through what it called its ‘second economy’, which produced military vehicles, tanks, artillery, firearms, ammunition. Eventually this was extended to include the production of chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons.

Military drills and the language of military readiness pervaded North Korean society. Kindergarten children practised with toy guns, older schoolchildren with real ones. The country was on a constant war alert. News reports constantly spoke of feverish preparations by the American imperialists and their southern puppets for another attempt to invade the North. Militarism had always been part of the culture of North Korea since the struggle of the Manchurian guerrillas against the Japanese had been used as the model and analogy for all endeavours; it was now amplified. Military drills and preparedness were useful for the regime as a means of disciplining and controlling the population as well as making it ready for the resumption of conflict. But the burden of a poor country devoting so much of its resources to the military made it difficult for the regime to sustain the high levels of growth it achieved in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Meanwhile, in 1964, Kim Il Sung publicly outlined his strategy for reunification. He called for the development of the ‘three revolutionary forces’. The first was to develop the revolutionary potential in the DPRK—that is, build up its military, economic, and ideological strength. This included not only industrialization and the expansion of its armed forces, but indoctrination of the population so they would be better prepared for reunification. The second was to strengthen the revolutionary forces in the South. This, Kim admitted, was the mistake of 1950; the people in the South had not yet been fully ready for the revolution. To this end, the policy of the DPRK was to encourage the people of the South to turn on their own government and turn to the North for support. Pyongyang carried this out by sending agents to contact sympathizers in the ROK and help them organize an underground Revolutionary Party for Reunification. Pyongyang felt that there was a real possibility that with its help their southern compatriots would rise up in support of unification under the DPRK. They could appeal to them as the real upholders of Korean nationalist aspirations. After all, the North was successfully modernizing without having foreign troops on its soil or selling out economically to the former Japanese colonial masters.

The third part of the strategy for reunification was promoting ‘the international revolutionary forces’. By this Kim meant forcing the withdrawal of American forces in the South, an obvious obstacle to reunification by force, through international pressure. This included gaining the support of the Third World for the DPRK’s cause and weakening the USA whenever possible. North Korea supported the North Vietnamese, for example, even sending some pilots in the hopes that, if defeated in Vietnam, the Americans would tire of their military presence in Asia. In the 1970s Pyongyang sought and succeeded in gaining membership in the Non-Aligned Movement. From 1975 to the early 1980s it had enough Third World support for the UN to regularly issue calls for the withdrawal of foreign (meaning American) forces from the Korean peninsula.

For the next thirty years after he first articulated it, Kim Il Sung’s foreign policy was built around pursuing these three revolutionary forces with the hope that he would see the reunification of Korea under his leadership. While it was a long-term strategic plan, from time to time his regime sought to speed up the process by stirring up trouble with and within the South. During 1967, the DPRK, hoping to take advantage perhaps of a USA bogged down in Vietnam, ratcheted up tension with a series of ‘incidents’ along the DMZ involving exchanges of fire. In January 1968, a group of North Korean commandos attacked the Blue House, the presidential mansion in Seoul. They came close to entering before being killed. On the same day the DPRK seized the US navy intelligence ship the USS Pueblo; it then held the crew captive. After months of negotiations they were released but the ship was kept as a museum, anchored at the spot where the General Sherman had been destroyed. During 1968, teams of commandos sent from the North landed along the east coast of the ROK lecturing the villagers and unsuccessfully trying to gain support for their liberation. In 1969, DPRK forces shot down a US spy plane. North Korea’s more aggressive stance, however, made no progress toward reunification. South Koreans showed little interest in being liberated and President Park’s elaborate security forces were able to round up and arrest the members of the Revolutionary Party for Reunification.

Following the lead of Beijing, which began talks with the United States in 1971 and welcomed President Nixon in early 1972, Pyongyang initiated negotiations with South Korea. The two countries in July 1972 agreed that all Koreans were one homogeneous people, one nation, that was for the time being politically and ideologically divided but would eventually unite, a view that few Koreans would disagree with. The two sides further agreed that reunification would be done peacefully and without foreign interference. This would take place gradually, starting with a confederation. South Koreans were excited by the possibility of the end of conflict and the movement toward unity. North Korea, however, lost interest in the talks when it became clear that neither Washington nor Seoul had any intention of having US troops withdrawn from the peninsula.

South Korea: authoritarianism, militarism, and heavy industry

In the 1970s, South Korea moved in a more authoritarian, militaristic direction, in some ways resembling the regime in the North. Park altered the constitution, enabling him to run for a third term in 1971 and then, following a surprisingly close vote against Kim Dae Jung (Kim Taejung), a relatively unknown opposition figure, took steps to consolidate his power. In 1972, he declared martial law and then created a new constitution that gave him broader powers. Under this constitution the president was elected by a National Reunification Board whose members Park selected; in this way he was able to remain president indefinitely without direct accountability to the public. He issued a series of presidential decrees clamping down on dissent, making the criticism of the president or the constitution a criminal offence. Political indoctrination increased; cities came to a halt at 5 p.m. and everyone froze to attention as the national anthem blared from loudspeakers. Military training was increased in the schools.

At the same time Park’s administration carried out a sweeping rural modernization programme known as the New Village Movement and launched a programme for heavy and chemical industrialization. The latter included construction of the world’s largest steel mill, as well as shipyards and petro-chemical plants. The switch from labour-intensive consumer industries to capital-intensive enterprises was viewed with scepticism by South Korea’s American economic advisers. But it reflected Park’s desire to both make the country more economically self-reliant and provide the industrial basis for military production. He even carried out secret plans to develop missiles and nuclear weapons; however, these were discovered and vetoed by the USA, which still held great leverage over South Korea.

Yet despite this authoritarian turn, Park never acquired full dictatorial powers. Although weakened there were still opposition political parties, newspapers, and private organizations, many with religious links, that carried on a vocal resistance to his policies. Student demonstrations continued, and there were sporadic outbreaks of labour unrest. A key factor limiting Park’s power was South Korea’s continued dependency on the USA for military support and as the prime market for its exports. The USA sometimes gave shelter to opponents or threatened reprisals for mistreatment of high-profile dissidents. Furthermore, the state, although repressive, was somewhat constrained by its ideological links with the West. The government in Seoul promoted anti-communism and ultra-nationalism but it also identified with the democratic world and taught liberal democratic ideas of government and society in the schools.

South Korea was, in fact, more connected to the global economy and global culture and its people far less isolated than those of its northern rival. Thousands travelled to the USA for education, millions watched American television, and the economy remained based on trade with the USA, Japan, and Western Europe, all of which had open democratic societies that many South Koreans admired. South Korea’s economic development remained primarily export oriented; even its steel industry was designed to be internationally competitive. It was also a more pluralistic society than the North. A factor in the greater pluralism was the rise of Christianity. Christianity grew after 1945 from less than 5 per cent of the population to perhaps one-quarter by the 1980s, making South Korea the second most Christian society in Asia after the Philippines. Most Christian churches avoided political involvement; however, some were involved in labour movements and in political opposition. As was true of the much smaller Christian community under Japanese colonial rule, their international connections gave them some protection from repressive authorities. Traditional respect for education gave university students some cover as well to act as the conscience of society protesting the corruption and abuses of the regime. Labour activists were able to survive despite repression by both government- and industry-employed thugs. The business community, generally supportive of the regime, also had its own interests to protect and sometimes resisted heavy-handed government interference.

In 1979, labour and political unrest broke out in the Busan area. As it rose to a crisis level Park Chung Hee was assassinated by the head of the KCIA, who objected to the president’s decision to suppress the protesters rather than negotiate with them. A brief period of political liberation, sometimes referred to as the ‘Seoul Spring’, was followed by the reassertion of South Korea’s security state under General Chun Doo Hwan (Chǒn Tuhwan) in 1980. Chun’s consolidation of power was accompanied by the brutal suppression of a popular insurrection in the south-western city of Kwangju. This Kwangju Incident would go on to haunt the Chun regime, which remained unpopular and ‘illegitimate’ to many Koreans. Chun continued with Park policies, with, at first, only some cosmetic changes. The nightly curfews and the standing at attention at 5 p.m. came to an end and students no longer wore military uniforms. However, from the mid-1980s the government reduced censorship and eased its harassment of political dissidents. South Korea in the 1980s was no longer moving in an authoritarian direction. Meanwhile, its economy continued to advance in the fast track.

While all this was happening the standard of living for most South Koreans improved considerably. In 1960, South Korean per capita income was the same as Haiti, a little lower than Ghana. A decade later it was much higher, although perhaps no more so than in North Korea. By the 1980s South Korean living standards had so dramatically improved that no one would think of comparing them with Haiti or Ghana. And by almost any measure of well-being, the vast majority were better off than most North Koreans. They were far better fed, better educated, healthier, living in more spacious modern housing, and had greater access to recreation and entertainment. The squalor that characterized southern cities with their beggars, children selling gum, dirty streets, and shabbily dressed poor had largely disappeared by then. One thing South Koreans shared with their compatriots in the North was the long hours they toiled. South Koreans did not have to do many hours of ‘volunteer’ labour or attend lengthy, compulsory ‘study sessions’ (see below) but at their company or organization they put in fifty or sixty hours a week. In fact, in the 1970s and 1980s, they worked more hours than those of any country where such records were available. Working conditions were often grim and dangerous. Young women often lived in ‘beehives’—tiny dormitories at work. The industrial accident rate was among the highest in the world. While living standards were improving, life was still hard and many South Koreans in the 1970s and 1980s emigrated abroad. Those who stayed at home were becoming increasingly restless.

North Korea: losing economic momentum, becoming a dynastic state

The North moved in its own eccentric direction in the 1970s and 1980s, evolving into a dynastic cult state, whose ideology became further removed from orthodox Marxism-Leninism. When Mao Zedong carried out his Cultural Revolution beginning in 1966, Kim followed with his less chaotic version. State propaganda praised him as a greater thinker. His juche (chuch’e) thought, a term often translated as ‘self-reliance’, became the ideological foundation of society. In 1972, a new constitution was promulgated to replace the one drawn up by the Soviets in 1948. It declared juche, ‘an adoption of socialism to Korea’, as the basis of the government. After the 1970s references to Marxism-Leninism disappeared. A great tower of juche thought was erected in the capital whose red flame stood out in the night skyline. North Koreans were required to study Kim Il Sung’s thought in weekly, semi-weekly, and even daily study sessions at their workplace. The state spent scarce foreign exchange buying pages in foreign newspapers extolling the great leader and his thought, and sponsoring Juche Study Societies overseas. Meanwhile, Kim’s cult of personality, originally modelled on Stalin’s, reached proportions so extreme as to strike even sympathetic foreign observers as bizarre. His portraits and statues were everywhere, his quotations were carved in giant letters on the mountainsides. From the early 1970s all citizens were required to wear a badge with his image.

A distinctive feature of the cult of Kim Il Sung that set it apart from other communist states was that it was extended to his family. His mother, father, great-great grandfather, and his first wife all became objects of patriotic devotion. This had been true from the early days of the regime but a heightened emphasis on his ‘revolutionary lineage’ in the 1970s coincided with the emergence of his son Kim Jong Il as his designated successor. This was done quietly at first: Kim Jong Il never appeared in public and was unknown outside the Party elite. Then in 1980, Kim Jong Il made his public debut at the Korean Workers’ Party Congress. Thereafter, he was shown on television and in the press accompanied by his father. His picture too appeared everywhere, and the younger Kim began to receive the adulation previously reserved for his father. North Korea had become a dynastic state.

Not only was the Kim family portrayed at the centre of the Korean nation, Pyongyang became its geographic centre. Previously, the North was the base camp from which the unfinished nationalist struggle for liberation would continue until the imperialists were driven out of the South and the country’s unity restored. The 1972 constitution declared Pyongyang not Seoul the nation’s capital. A new Pyongyang-centred nationalism was emerging. In the early 1990s, archaeologists, at the suggestion of Kim Il Sung, discovered an ancient civilization based at Pyongyang, which was proclaimed the cradle of Korean culture.

While the ideology evolved, economic policies remained frozen in the early years of the regime. Unlike most communist states that made some concessions to private markets, the DPRK maintained total state control over the economy. Lacking the foreign exchange to import technology, the regime simply tried to apply more labour to meet production goals. Soldiers devoted much of their time to construction projects and helping to harvest crops. Students spent as many days labouring in the fields and at construction sites as in school, and government offices were closed on Fridays so that all employees could do ‘volunteer’ labour. The state organized ‘speed battles’ to meet unrealistically high targets, which were almost always falsely declared successful. North Korean workers and farmers were bombarded with exhortations to inspire them as they toiled at weekends and after work. The same methods, however, resulted in diminishing returns. It is difficult to determine growth rates in North Korea where even basic statistics are kept secret, but its economic growth after the early 1970s appeared to have slowed down. In the 1980s, it was barely growing at all.

What little economic growth it achieved in the 1980s was in good part due to aid from the Soviet Union, including the supply of petroleum at well below the market price. Still the DPRK found itself desperately short of foreign exchange since it produced little that anyone wanted. As a result, the state began to resort to criminal activity to raise foreign exchange. It produced narcotics delivered by its diplomats in their pouches, exported counterfeit cigarettes, printed counterfeit US currency, and engaged in arms smuggling.

The contrast with South Korea could not be greater. While the ROK in the 1980s was becoming an export powerhouse selling electronics, appliances, steel, ships, and textiles, North Korea was engaged in illegal enterprises to earn even modest amounts of foreign exchange. While the ROK’s economic growth was accelerating in the 1980s, the DPRK economy was stagnant. While in South Korea living standards were rising sharply, North Koreans after 1980 were experiencing serious food shortages and malnutrition. In the economic competition between the two Koreas, South Korea was clearly winning.