THE CIVIL WAR FORGED A SOUTHERN WHITE IDENTITY THAT has persisted to the present day. For all the advances in racial cooperation that flowed out of the civil rights movement of the 1960s and for all the cultural diversity that accompanied the economic boom celebrated in Atlanta’s hosting of the Olympics in 1996, white identity politics remains alive and well in the South. A longing for a South that could have been—should have been—shapes much of that identity. Unable to let go of the Confederate past and the belief that hypocritical and power-hungry Yankees unjustly attacked heroic, liberty-loving Southerners and crushed their bid for independence through the sheer weight of their numbers and material resources, many Southern whites continue to find meaning and purpose in their lives by clinging to a romanticized vision of a mythic Southern past.

No Southern writer wrestled more imaginatively or painfully with how the past intrudes into the Southern present or how memories are remembered and recast than William Faulkner. “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” asserted Faulkner. In a memorable passage from his 1948 novel Intruder in the Dust, the novelist imagined the longings of Southern boys to undo the results of the Civil War, to turn defeat into victory, by returning to “the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863” when Pickett’s men were poised for their charge at Gettysburg. A modern observer tempted to dismiss Faulkner’s words, written more than fifty years ago, as trite in today’s South would do well to ponder the motivations of present-day Confederates who march in the sweat and grime of their authentic uniforms in reenactments or the passions and contentious politics stirred up in the public display of the Confederate flag.

Fort Defiance testified to the elite status of the Lenoir family.

(Source: North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North

Carolina-Chapel Hill.)

The bucolic setting of Fort Defiance overlooking the Yadkin River was suggestive of the estate of an English country gentleman.

(Source: North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.)

No one knew better that Gettysburg could not be refought and won than the Southern whites who survived the carnage of that terrible war. They were physically beaten, and they knew it. Out of that physical defeat, however, they forged a spiritual victory, what one Missouri veteran at a Confederate reunion in 1906 termed “a new religion.” A blend of Protestant evangelicalism and Southern romanticism, this “new religion” gave meaning to their collective suffering by re-imagining the Old South as a sacred place baptized in the blood of its selfless Christian soldiers who sacrificed their lives against unholy Northern invaders. Here was a faith that by immortalizing the departed filled a void in lives torn apart by the loss of loved ones. Like all religions, it invested cultural symbols and material artifacts with a sacred status. Dutiful worshippers venerated the Confederate flag, specifically the Southern Cross that originally was a battle flag, the tattered gray jacket of the common Johnny Reb, and the song “Dixie” in rituals of commemoration spontaneously organized at first by Confederate widows and then more formally by organizations such as the United Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Robert E. Lee, Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, and Jefferson Davis headed a group of Confederate leaders elevated into the pantheon of Christian sainthood.

Underpinning this sacred image of the South was the mythology of the Lost Cause, a retelling of the history of the slave South and the causes of the Civil War spread by ex-Confederates after the war. For Wade Hampton, a celebrated ex-Confederate cavalry commander, such a retelling was nothing less than the responsibility of all true Southerners. “As it was the duty of every man to devote himself to the service of his country in that great struggle which has ended so disastrously … so, now, when that country is prostrate in the dust, … every patriotic impulse should urge her surviving children to vindicate the great principles for which she fought.” The efforts of Hampton and others were so successful that by the 1880s the claims of the Lost Cause dominated not only the Southern white memory of the sectional conflict but also were beginning to shape the Northern memory as well.

Best understood as an effort toward moral rehabilitation, this version of Southern history transformed the tensions and conflict of the Old South into a timeless image of social harmony and genteel grace. Its adherents did not so much erase enslaved African Americans from the story as they caricatured them as the contented, indeed happy, servants of benevolent Christian masters who cared for their every need. Led by high-toned men of aristocratic lineage, the so-called Cavaliers, Southern whites valiantly struggled to defend their liberties and way of life from the unceasing assaults of money-grubbing Puritanical Yankees who hypocritically attacked slavery only after they had ceased making money off the institution. When the war came, the South fought only in self-defense and only for the sacred principles of constitutional freedoms and self-government bequeathed to them by their Revolutionary forefathers. United in the holy, legitimate cause of the Confederacy that had nothing to do with the defense of slavery, Southern whites proved themselves worthy of Christian martyrdom as they sacrificed their lives and property on behalf of their independence.

As depicted in this 1830 drawing with the family coat

of arms, General Lenoir was the personification of

patriarchal authority.

(Source: North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library,

University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.)

Left out or ignored in this rendering of the Old South and the Confederate experience were the leading secessionists who repeatedly insisted that the South had to leave the Union in order to protect slavery. Nowhere to be found are the white Unionists, the growing bands of deserters from Confederate armies, and the African American slaves who seized every opportunity presented by the war to gain their freedom. As William W. Freehling recently argued in The South vs. the South, Southerners, white and black, spent much of the Civil War fighting against each other. Also missing from the accounts of the Lost Cause are the complexity and diversity of late antebellum Southern society, the violence and often brutal discipline that structured the institution of slavery, and the conflicts experienced by many Southern whites as they struggled to reconcile their belief that slavery was morally unjust with their even stronger conviction that emancipation would plunge the South into racial chaos and horror.

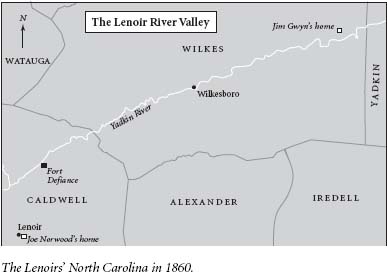

One way to pull together and make sense of these missing elements is through a story that opens a window into the nineteenth century South and explores how one Southern white came to identify himself in terms of his Confederate experience. It’s a story centered on Walter W. Lenoir, a slaveholding North Carolinian who, despite morally opposing slavery and preparing to move to the free state of Minnesota in 1860, enlisted in the Confederate army and became a fervid Confederate.

Walter Lenoir’s South lies outside the South of the popular imagination. It was not a wealthy region of sprawling cotton and sugar plantations but of mixed agriculture and a small minority of slaveholders engaged in a variety of economic activities. Unlike the Lower or Cotton South, which is too often identified with the South as a whole, the dominant political party was not the Democrats committed to the defense of slavery as a positive good and championing states’ rights arguments justifying secession from the Union. Instead, across the foothills and mountains of the western North Carolina that Walter knew so well, the politically moderate Whigs were the majority party, and they consistently upheld the value of the Union and looked to economic development within it as the key to the future prosperity of the South.

In the Lower South, where slaves made up close to half of the total population and where nearly two in five white families owned at least one slave, the paramount need to defend slavery was so great that the mere election to the presidency of an anti-slavery Republican was sufficient to trigger a successful secession movement. Citing Lincoln’s election as an intolerable threat to slavery, secessionists carried seven states out of the Union stretching from South Carolina to Texas. Delegates from these seven states met in Montgomery, Alabama, in February 1861 and fashioned a new Southern government, the Confederate States of America. Still, eight of the fifteen slave states hung back. In these states, slavery lacked the overwhelming centrality that it had in the Lower South as both an economic investment and a means of racial control. Across the Middle and Upper South, home to two-thirds of the South’s white population, voters rejected secession by two-to-one margins in a series of special elections. Everything changed with lightning speed in mid-April 1861 with the fighting that erupted over Fort Sumter and then Lincoln’s call on the states for militia troops to put down what he defined as a rebellion against the U.S. government. Almost uniformly denounced in the South as a declaration of war, Lincoln’s call for troops converted wavering Unionists into Confederates committed to defending their homes and families against what they saw as an unconscionable invasion.

As revealed by Walter’s transformation during the secession crisis from defender of the Union to supporter of the Confederacy, secession was a process that affected Southern whites in different ways at different times and not a spontaneous outpouring of sentiment across the entire South against Northern aggressions, real or perceived. Like many Southerners, Walter’s family was ambivalent about secession and going into the war. The pressures of history, as Faulkner understood, shaped and warped and bent the four brothers who got dragged into the cataclysmic conflict. One brother sat out the war; one raised a military company but then, without ever having seen combat, left the army; one committed suicide; and one lost a limb in battle and became a loner, living in isolation for the rest of his life. For him, the past truly was never past and the Cause that was not lost to begin with, became a Lost Cause that was never there in 1861.

For Walter, and a surprisingly large number of his friends and kin, emancipation came as the release from a burden and it was accompanied by something approaching relief. The Union Army, as Walter perceptively noted, would not allow emancipation to explode into a bloodbath costing the lives of Southern whites. While the Union military was acting to stabilize the very social relations it was upending, recently constructed Confederate identities began to unravel. Anti-Confederate sentiment emerged early in the war in western North Carolina. Once the reality of a long, cruel war set in, disaffection spread and became a major problem among both civilians and the soldiers. Tom Norwood, Walter’s nephew, informed him in the summer of 1864 that the men in his old regiment, the North Carolina 37th, were “not only tired but sick of the war.”

Southern whites reacted to defeat in the Civil War in a variety of ways ranging from depression and self-exile to a willingness to reach an accommodation with the victors. Common to most of these responses, however, was a unifying set of themes: a refusal to acknowledge that they had done anything wrong in bringing on the war; an honoring of their Confederate dead and their sacrifices; a deeply rooted denial that the freed slaves were “ready” for freedom or should be allowed to participate in public life on terms of equality; and a search for a new foundation for a prosperous economy now that slavery had been destroyed. Walter’s postwar search for a redemptive meaning to his life speaks to these themes with an intensity and purpose that were nothing less than a strategy for coping with bereavement and a crushing sense of loss. For Walter, and many other Confederates, the war had never really ended. All that had changed with the surrender of Confederate armies was the focus of their defense of the South.

What follows then is Walter’s story. It is a story that invites the reader to confront the ambiguities and complexities of a South that have been effaced in the haze of the Lost Cause mythology. And from Walter’s story, they will learn that an abiding and culturally unifying sense of Southern white identity was a product of defeat in the very Civil War that so many Southerners sought to prevent.

For the Faulkner quotes, see William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun (New York: Random House, third printing, 1950), p. 92 and Intruder in the Dust (New York: Random House, 1948), p. 194. The Wade Hampton quote can be found in Richard Gray, Writing the South: Ideas of an American Region (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997), p. 76, a work that offers a finely grained account of the ways in which Southern writers have shaped how Southerners imagine and re-imagine their past. Tom Norwood’s letter to Walter Lenoir on July 18, 1864, is in the Lenoir Family Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The broad themes mentioned in the prologue and the historiography that addresses them are discussed in greater depth in the afterword. A special note can be made here, however, of the myth of the Lost Cause which has loomed so large in how Southern whites remember the Civil War. The essays edited by Gary W. Gallagher and Alan T. Nolan, The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000) explore how the Lost Cause falsified the past and, in so doing, assumed a life of its own. For an often humorous but still serious look at those Southern whites who still passionately embrace the Lost Cause, see Tony Horwitz, Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1998).