3

3

INEQUALITY AT WORK

A GOOD JOB CAN PROVIDE AN AMPLE PAYCHECK, BUT THE best jobs offer much more. By affording a way to build wealth and economic security, a quality job allows the holder to optimize her family’s health and welfare, to purchase and maintain a home or secure stable rental housing, and to save for a comfortable and dignified retirement. Along the way, working fosters a sense of self-worth and contributes to the health of a community. Yet, just as work propels well-being for some, it also drives inequality. The rising earnings of a relative few are one major source of the highest levels of economic inequality since the 1930s. Just as important, however, are the potential wealth gains associated with work. As crucial as work is, our contemporary employment landscape has accelerated toxic inequality.

Today, the quality of work and the benefit structures and wealth-building pathways that jobs provide diverge sharply along lines of occupation and employment sector. Increasingly, there are two classes of jobs—those that build and preserve wealth and those that keep working families stuck in place. Jobs in the first category usually provide higher incomes and regular employment, but they also offer benefits such as paid sick leave, dependent care, health care, and structured savings or retirement plans, all of which have become keys to family prosperity. Jobs on the other end of the spectrum don’t just provide lower wages and less regular work; they also offer none of those keys. For example, about two of every five workers (39 percent), when sick, must either go to work regardless or stay home without pay and risk losing their jobs; 87 percent of high-wage workers have paid sick days, but only one in five low-wage workers does. Consistent work, job flexibility, and work-based resources and benefits enable families to build and protect wealth—but only some jobs provide what can be called “employment capital.”1

Employment also widens the racial wealth gap. The pathways to well-being and wealth that jobs offer diverge along racial lines, and access to employment capital differs depending on race. Black families are more vulnerable than white families to disruptions in employment and continue to be concentrated in jobs that pay less and offer fewer wealth-building opportunities. This, in turn, undermines their prospects for building wealth over the life course. The stories of the Ackermans and the Medinas reveal the power of work in shaping families’ futures.

ALLISON AND DAVID ACKERMAN WERE BOTH THIRTY-THREE years old when we spoke to them in 1998. Married for ten years, they were raising three youngsters, ages six, three, and two. They had lived in St. Louis’s South County their entire lives. Jobs in human resources and public safety at large universities provided a 1998 family income of $83,000, placing them solidly in the middle class. Taking equity from their first fixer-upper home and adding some parental financial assistance, they had bought a modest three-bedroom brick house in a new development in 1990. They held a few stocks and mutual funds, had a savings account, owned a boat, and were vested in workplace pension plans, all of which brought their financial assets to about $90,000, not including their home equity.

Twelve years later, Allison and David had experienced setbacks, but their financial footing nevertheless remained firm, and their children were thriving. Their oldest son, Peter, was a sophomore in college; their daughters, Emily and Kate, were in high school and planning to follow their older brother to college. Their $125,000 combined family income had more than kept pace with inflation—rare among American families—and the Ackermans enjoyed $10,000 more in purchasing power in 2010 than they did in 1998. They still lived in the same house, and the family’s financial wealth had risen to $368,000, excluding home equity. Their work-based retirement plans provided their largest wealth reserve by far. Other financial assets included modest savings accounts, their children’s college accounts, and a vacation home in the Ozarks. All in all, life had been good to the Ackerman family.

Allison still worked at the same university, now as an accounting manager. Her employer provided a robust benefit package, including pension and health-care plans. Allison’s employment capital enabled her children to get ahead in life. Her employee benefits provided financial assistance for them to attend any school they chose, paying up to half the cost of tuition at her private university, which fully covered Peter’s tuition at the University of Missouri. “We have been extremely lucky,” the couple acknowledged.

David’s career took a different path. Over time, he steadily assumed greater and greater responsibilities for four different employers. Starting as a public safety dispatcher, he rose to manage an emergency joint dispatch center for safety communications for the county. Yet David’s steady twenty-four-year ascent collapsed in 2010. Two weeks before we spoke to him, he had lost his job of seven years. David blamed “politics”—a newly elected mayor in one of the municipalities wanted someone else in his position. David was still digesting the job loss and figuring out his next steps, but he was not worried. As he was collecting unemployment insurance, with another family member working full-time at good wages and with assets that provided an ample protective cushion, two weeks without a paycheck was not stressing the family.

With the economy downsizing on the heels of the Great Recession and an uneven job recovery heavily tilted toward low-wage jobs, David Ackerman joined millions of other Americans in confronting the challenge of finding new work and replacing lost income. David ended up spending half a year unemployed—much longer than he anticipated. His new job, supervising communications and records at the safety department of a public institution, offered less responsibility and paid considerably less. In the decade since 2006, one-third of all households experienced unemployment, and, like David, most people who lost their jobs returned to work at lower wages. Situations like David’s are increasingly common, and David’s unemployment was painful for him and challenging for his family. Yet Allison’s employment capital and the assets the Ackermans had built over their careers prevented it from becoming a disaster. Many other families aren’t so lucky.

Through David’s experience the Ackermans witnessed how work is becoming less stable and more contingent for many Americans. They also noticed their community changing. When they bought their home in 1990, their South County subdivision was new, and the community was solidly middle-class by any measure of income and occupation. But a changing economy and stalled living standards on a national level reverberated locally. Appraising his neighborhood in 2010, David said, “You know, I don’t know that I know the definition of middle class anymore, but I would think it’s probably… middle working class.”

Statistically, the Ackermans remained members of the middle class, but once David took his new, lower-paying job, the family’s income purchased less than it did when we first talked to them in 1998. Allison and David felt this squeeze acutely. David, like 85 percent of middle-class Americans polled in a 2012 survey, said it was more difficult to maintain living standards than it had been ten years earlier.2 A little more than six in ten middle-class families reported having had to cut back household spending. Today, it is both harder to get into the middle class and harder to stay there than at any time since World War II. One recent study found that the middle class—defined as the share of families earning between two-thirds of and twice the national median income, or between $42,000 and $126,000 in 2014 dollars—had shrunk from 61 to 49 percent of the population since the 1970s.3 Middle-class economic insecurity increased by 42 percent from 2004 to 2010, as measured by family assets.4 The Great Recession accelerated a major shift toward middle-class insecurity, one that the Ackermans experienced personally.

Nevertheless, when it came to building wealth, the Ackermans were a success story. They were among the ninety-seven families we talked to whose wealth increased between 1998 and 2012, and their jobs were crucial to their gains. Perhaps most important, Allison’s employer took a mandatory 5 percent pretax contribution from her salary and invested it in a defined contribution retirement account. For every dollar Allison contributed, her employer added $1.70 more. In David’s work career, a couple of his employers also offered similar retirement accounts. As a result, over twenty years of working, the Ackermans had accumulated more than $350,000 in workplace-based retirement assets. This kind of automatic, matched savings mechanism is central to how American families “save” money and generate wealth. Over half of the wealth builders we talked to had access to some sort of employer-matched savings scheme, a centerpiece of the employment capital provided by the best jobs.

For all the difficulties they faced in the wake of the Great Recession—temporary job loss, lowered wages, and a slumping neighborhood—in real ways the Ackermans represent a model of family well-being and success in passing opportunities and social status along to their children. Quality jobs that provided access to employment capital were crucial. Such jobs, however, have become more the exception than the rule among American workers.

The crucial role of employment capital becomes clear when we compare the Ackermans’ experience with that of India and Elijah Medina, the middle-class Spanish Lake family introduced in the previous chapter. In contrast to the Ackermans, the Medinas had weak employment capital. Although India and Elijah had skill sets similar to Allison and David, they worked for a series of small organizations and firms at lower-paying jobs that did not provide the same sort of ample health insurance, structured and matched retirement plans, and financial support for children’s postsecondary education. India was a bookkeeper, and Elijah worked at two service jobs, one with a national restaurant chain. Elijah also collected, refurbished, and sold boats as a side business. Between 1998 and 2010, their actual family income increased from $50,000 to $62,000, also placing them in the middle class. These income gains came through great effort: the hard work needed to earn regular raises and promotions, Elijah’s decision to take on a second job, and added income earned through self-employment. Nevertheless, the Medinas’ 2010 paychecks really represented a decline in living standards because their earnings had not kept pace with inflation.

Moreover, the Medinas had built up far fewer assets than the Ackermans. Their routine expenses were higher, in no small part because India’s employer’s contribution toward the cost of family health insurance coverage was considerably less than that of the Ackermans’ employers. The Medinas had tried to save by setting money aside, but their retirement accounts were neither mandatory nor matched by their employer. Like many other American families encountering tough times without the benefits of substantial employment capital, they tapped these small nest egg accounts to weather several family crises. As a result, in 2010 the Medinas had about $12,000 in retirement accounts, mostly in one India started a few years earlier; she wished she had started it even sooner. None of the Medinas’ employers offered college savings plans or other assistance for children’s education. When we talked in 1998, India and Elijah’s youngest daughter, Tina, had college aspirations, but the couple’s employers did not provide the support that might allow the family to realize that dream. (Research has shown that children whose families have even small amounts of dedicated college savings are three times more likely to attend college.5) In 2010, Tina was not college bound; she worked as a receptionist at a local hotel. When we asked about Tina’s plans for college, India was not optimistic: “[Tina] says she plans to go back to school, but we’ll see.”

When we spoke to them in 2010, the Ackermans expressed great confidence in the future, with $350,000 in their retirement accounts and the means to put their children through college. The Medinas were anxious, especially about what getting older would mean for them. Peter Ackerman, studying at the University of Missouri, was in the midst of securing his own middle-class future, while Tina Medina, working as a receptionist, seemed at risk of losing the hard-earned middle-class status her family had attained. What separates these two families? In no small part, the government-backed benefit and policy support structures and quantities of employment capital available to the Ackermans and the Medinas through their jobs made all the difference in charting divergent futures for their children. These differences also explain why, even though skills seem similar, the Ackermans’ family income is greater and why their economic and retirement security is far more robust. Access to wealth-building escalators on the job can mean the difference between stability and instability, between moving ahead and losing ground.

It should not matter that the Ackermans are white and the Medinas are African American. Nevertheless race is a crucial factor putting the children of these two families, Peter and Tina, on their differing trajectories. Innate ability, character differences, and superior values play little role in their future prospects, despite the readiness of many commentators to attribute racial differences in mobility and educational achievement to such factors. Peter and Tina were very different people, with their own interests and passions, but both were equally determined to get ahead in life. But their parents’ jobs and benefit structures, and the sort of wealth accumulation and economic status those jobs enabled, largely dictated their paths. In the United States today, access to the best jobs with benefits diverges sharply based on race.

Similarly educated, with similar skills and similar ambitions, the Ackermans and the Medinas were nevertheless divided by vast differences in wealth accumulation, retirement security, and life chances. The Ackermans help illustrate the kinds of work situations that provide employment capital and thereby enable opportunity and mobility; the Medinas suggest what is missing in work situations that make well-being more contingent and fragile. Today, fewer and fewer families have access to opportunities like those the Ackermans enjoyed. And they and the Medinas both are part of a larger trend in the United States toward employers and corporations hollowing out good, middle-income jobs and hence the middle class.

THE EMPLOYMENT LANDSCAPE HAS CHANGED DRAMATICALLY in the United States. In 1970, General Motors (GM) employed 550,000 workers. It was the largest private employer in the United States, paying good salaries and offering benefits similar in fundamental ways to those the Ackermans enjoyed. Nearly half a century later, a corporate-driven globalizing economy has produced a major employment transformation. In 2015, Walmart was the largest American employer, with over 1.3 million workers at predominantly low-paying, low-benefit jobs—jobs more like the Medinas’. According to one estimate, Walmart’s low-wage workers cost US taxpayers an estimated $6.2 billion in public assistance—including food stamps, Medicaid, and subsidized housing—because their wages are so low that they qualify for those safety net programs.6 Walmart’s average salaries are under $10 an hour; GM’s starting wage in 1970 was the equivalent of $23.58 in 2015 dollars. The transformation from GM to Walmart captures the grand sweep of America’s changing job landscape over recent decades.

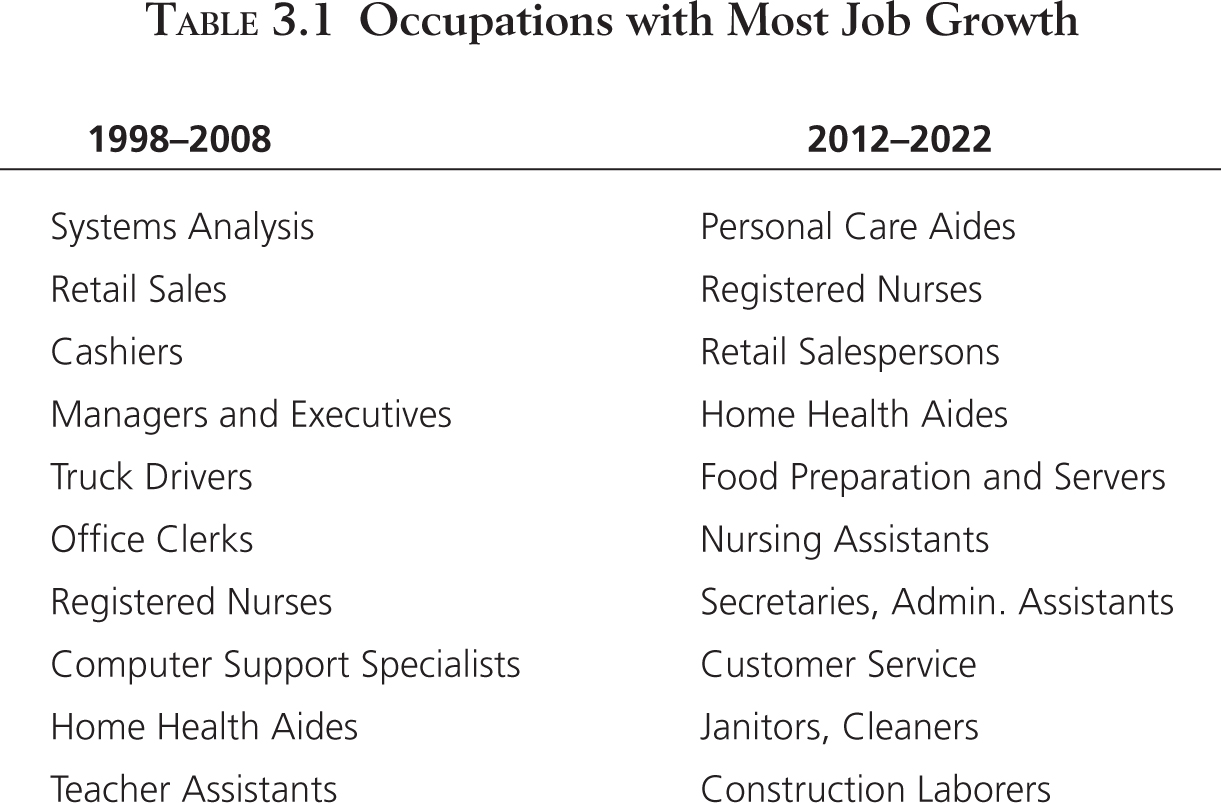

National data confirm how rapidly the United States is moving in this direction—toward fewer jobs like the Ackermans’ and more like the Medinas’. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has accurately projected job growth in the United States for over twenty years. The long-term trend toward lower-paying and less-skilled service jobs was already plainly evident as we embarked on our initial family interviews in 1998. According to BLS data, those occupations with the largest growth between 1998 and 2008 were already tilting toward jobs that required less education and skill and paid people a lower return on their work. The BLS job-growth projections for 2012 to 2022, shown in Table 3.1, further extend the trend away from middle-income jobs. Employers need fewer executive-functioning skills, while low-wage jobs without career ladders leading to more responsibility and better pay are rising.7

This sweeping occupational shift away from middle-income jobs is part of a larger economic transformation since the early 1970s as the United States, like the world’s other most developed nations, has positioned itself in the global economy. Industrial sectors have shrunk inexorably in size and economic impact, while service and health sectors have become the prime engines of increased economic output and employment expansion. The rate of service-sector expansion and especially the return from work on newly created service jobs are closely related to wage inequality. Women and workers of color have been greatly impacted by this transition because their employment is disproportionately concentrated in the service sector. Scholars, commentators, and politicians have debated ferociously about the fragile, anxious, squeezed, and declining middle class that has resulted from the hollowing out of mid-wage jobs. Arguing the causes for this transition, some point to a globalizing economy and deindustrialization, others to new technologies and machines, and still others to political factors such as liberalizing trade agreements, weakened labor unions, and a dwindling minimum wage. Regardless, the transformation of American work has had powerful effects on families like the ones we talked to—who were less concerned about the origins of these changes than with making their way through this altered landscape. The real pain and deeper struggles families face as a result of work and pay transformations, and the reasons behind them, may reverberate in national elections as politicians pander to the public and the media by shifting the conversation to unfair trade, imports, lost jobs, and immigration.8

The Great Recession sped up the transformation of American employment while starkly revealing longer-term effects on unemployment and underemployment, lower labor force participation, diminished work hours, and lower hourly wages. Not simply collateral damage associated with episodic economic downturns, these changes have become baked into the new economy. The devastating result of this changing employment landscape has been a lower standard of living for most families in the United States. In the immediate shock of the recession, 8.4 million people lost work, and median income for working-age families dropped by a tenth from where it had been in the first years of the new century. The economy contracted by 5.1 percent. One in seven Americans was living in poverty, and one in five children was growing up in a household below the poverty line. And these aggregate numbers mask how the imploding economy more harshly devastated young families, those without college degrees, and families of color. Although the Great Recession officially ended in June 2009, many of the families we interviewed between 2010 and 2012 continued to experience its impact profoundly. In 2013, median household income was $52,250, 8.0 percent lower than in 2007, the year before the recession began, and 8.2 percent lower than the 1999 peak.9

Accelerating an employment transformation already in the making, the Great Recession produced a “new normal” in which more and more Americans find themselves in the position of the Medinas. By 2014, the nation’s payrolls had rebounded to pre-2006 highs, but the working-age population had also grown over those years, making the rebound less impressive. Moreover, the vast majority of job losses during the recession were in middle-income occupations, which have largely been replaced by lower-wage jobs. Mid-wage occupations (those paying between $13.83 and $21.13 per hour) made up about 60 percent of the job losses during the recession. But those mid-wage jobs have made up just 27 percent of the jobs gained during the recovery. As of mid-2014, total employment in the relatively high-paying construction and manufacturing sectors was down more than 3 million as compared to before the recession. Other sectors of the economy, such as food preparation, temp work, and retail sales, have added 3 million jobs. Average hourly pay of food and sales workers ranges from $12 to $16. These lower-wage jobs, with no or meager benefits, have continued to reshape the economy since the recession. In contrast, the lost jobs in manufacturing and construction paid between $24 and $27 and often had health, family, and retirement benefits.10

The declining share of middle-income jobs since the 1970s reflects a polarizing labor market that puts little value on routine work but offers ever-bigger rewards to those with specialized knowledge and skills. From the end of World War II to 1973, employers shared huge gains in productivity somewhat equitably, resulting in the doubling of American living standards; since the early 1970s, however, they have uncoupled the productivity-to-wages nexus. Between 1979 and 2013, productivity grew 64.9 percent, while annual inflation-adjusted income for 80 percent of the workforce grew just 16 percent. This loss of shared prosperity for the many did not affect the few as they commandeered greater incomes at the top of the ladder—the top 1 percent gained 174 percent, and the next 19 percent of highest incomes flourished by 58 percent. Productivity grew eight times faster than typical worker paychecks, and living standards for most workers stagnated.11

Family strategies to compensate for blocked growth in living standards include working more hours and deferring retirement, working more than one job, combining regular jobs with self-employment, and sending additional family members into the paid workforce. As a result, families have increased their on-the-job working hours significantly since 1970, working 14.5 percent more hours each week, or eleven additional weeks each year, in an effort to keep pace.12 The increased work time is greater in families with lower-paying jobs. The additional hours come largely from people working more than one job and from women entering the paid workforce. Indeed, the number of family members working has grown significantly. From 1970 until the Great Recession, the average number of workers per family rose to 1.45 from 1.16. This increase is even more substantial considering the average family size has decreased by 25 percent since 1970. More members of smaller families spent more time working. Such an increase in family work hours can erode the quality of family life, even if family incomes keep pace.

The working experience of the Ackermans and Medinas illustrates a larger transformation in America’s employment landscape, away from middle-class jobs and jobs with significant benefits toward low-paying jobs with few benefits, accelerated by the Great Recession. The postrecession job recovery has centered on stagnating lower wages and few benefits. Moreover, the Ackermans enjoy the protection of robust workplace benefits that endow their family’s future but are largely unavailable to the Medinas. Precisely these sorts of benefits are becoming rarer and rarer as employers shift the employment landscape and it becomes polarized. The Ackermans’ and Medinas’ stories layer in racial wage differences as well. Whites disproportionately hold the kinds of quality, wealth-escalating job benefits so crucial to the Ackermans’ well-being.

SINCE THE RECESSION, WAGES HAVE STAGNATED, WITH WORKers of color especially poorly off. In 2013, the median weekly earnings for a full-time worker were $797. This is a scant $2 more than ten years earlier. Furthermore, earnings differ sharply depending on race and ethnicity, with Hispanics and African Americans earning considerably less than whites and Asians. In 2013, median weekly earnings for full-time wage and salary workers were $578 for Hispanics and $629 for African Americans, compared with $802 for whites and $942 for Asians.13 African American workers received seventy-eight cents and Hispanics seventy-two cents for each dollar paid to white workers. Although some of this distance results from differing education, skills, and occupations, the distance narrowed but significant gaps remained even within similar occupations. For example, among professionals working full-time, African Americans’ salaries are 85 percent of whites’.

Pay differences by race readily convert to income and wealth inequality. But there is more to the story. Furthermore, as the Ackermans’ story suggests, looking at wages alone can lead us to underestimate the magnitude and significance of income and wealth inequality. Several important items in Allison Ackerman’s total compensation package are hidden when we examine her earnings. Specifically, her employer contributed about $5,100 annually to her defined contribution retirement account; it paid about $5,500 toward the cost of her family’s health insurance; and critically, it paid her son’s $20,000 tuition. Allison’s paycheck masks approximately $30,600 worth of benefits. While the Ackermans are liable for taxes on the tuition benefit, the health-care benefit is not taxed, and taxes on the retirement account are deferred. Allison’s actual paycheck—her official earnings—severely underestimates the actual resources and protections her job provides. The related tax exemptions and deferrals also amount to extensive and concealed public subsidies. Paid sick leave, vacation and personal days, disability insurance, and stable work are further benefits, harder to quantify but indispensable to economic security.

We have seen how the kinds of quality jobs held by the Ackerman family are enormously valuable, increasingly rare, and harder to access for nonwhite workers. Many efforts to combat inequality have simply focused on removing barriers in education and employment that keep nonwhite workers from jobs with higher incomes and hearty benefits. Much progress has been made in legislation and employment practices and policies, such as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; the Equal Pay Act of 1963; Titles I and V of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990; and the Civil Rights Act of 1991, providing damages in cases of intentional employment discrimination. In addition, employers offering retirement accounts must market them to all eligible workers, not just to top pay grades or management. Liberals have traditionally held that removing barriers to opportunity is the silver-bullet answer to eliminating inequality, and the passage of major employment and civil rights laws has eliminated much formalized and explicit discrimination. Yet a growing body of research has begun to push past this orthodoxy and proposes that, as important as removing obstacles to opportunity may be, we need to dig deeper.14

The view that individuals have difficulty finding and keeping decent, mid-wage work due to inadequate social skills and a lack of job preparation and competence underpins a plethora of work-training programs. Addressing this opportunity obstacle is critical; yet it puts the onus of mobility entirely on individual workers. Many questions remain unaddressed, and I will follow up on just one: the financial gain of better jobs for blacks and whites. The very robust educational emphasis on inequality assumes that gaps will narrow considerably as we close in on college-completion parity. The tremendous gain in lifetime earnings due to attainment of a college degree over a high school diploma ($1 million), just some college ($700,000), or an associate’s degree ($500,000) is well documented, impressive, and important for individual mobility and better job security. While removing obstacles to college completion, whatever they may be, is crucial, we also need to ask whether college degrees result in considerably more financial gain for whites than blacks.15

Even when people of color get higher-earning jobs, because they are less likely to have good benefits, their paychecks do not translate into similar financial gain as for whites. Liberal and mainstream economic theory assumes that equal opportunity is the path to parity. This ignores the fact that equal achievements on the job and fatter paychecks yield unequal wealth rewards for whites and African Americans. Not surprisingly, increases in income are a major source of wealth accumulation for many US families. However, research by the Institute on Assets and Social Policy shows that similar income gains for whites and African Americans have a very different impact on wealth accumulation. Every $1 increase in average income over a twenty-five-year period converted to $5.19 wealth for white households but added only sixty-nine cents of wealth for African American households. The dramatic difference in wealth accumulation from similar income gains has its roots in long-standing patterns of discrimination in hiring, training, promoting, and granting access to benefits that have made it much harder for African Americans to save and build assets. Furthermore, broader family networks entailing mutual obligations tip priorities toward financially helping others at the expense of their own savings. As previously described, black workers predominate in administrative, support, and food services, which are least likely to have employer-based retirement plans and other benefits due to discriminatory factors such as occupational segregation that concentrates them into jobs offering lesser packages. As a result, wealth in black families tends to hover around what is needed to cover emergency savings, while wealth in white families far exceeds the emergency threshold, allowing them to save or invest additional dollars of income more readily.16

The statistics cited above about divergent wealth gains from rising incomes compare change in median wealth over twenty-five years for typical white and black households. Yet we already know that the average white family starts out with abundantly more wealth and a significantly higher income than the average black family. When whites and African Americans start off on a footing with similar wealth portfolios, gaps in wealth gains from similar rising income narrow considerably.

One of the most widely watched indicators of an economy’s health is the unemployment rate. Unemployment is also the most common cause of pressure on family finances, stress in family relationships, and changes in family members’ life trajectories. Prior to the Great Recession, the US unemployment rate had been at or below 5 percent for the previous two and a half years. It peaked at 10.0 percent in October 2009. At the end of 2014, official unemployment was at 5.8 percent, but that figure climbed to 11.5 percent once part-time workers who wanted full-time work and those marginally attached to the labor force were added in. In addition these figures mask the pervasive reality of unemployment over the long run: over a twelve-year period (1998–2010), two in five families had a working member who experienced at least one spell of unemployment.17

All families do not experience employment disruptions similarly. Unemployment is a more frequent and prolonged event for African Americans than it is for whites. The national unemployment rate in 2013 for African American workers was double what it was for whites—13.1 percent for African Americans and 6.5 percent for whites—and the Hispanic rate was 9.1 percent.18 The same phenomenon also appears in longitudinal national data. Between 1999 and 2012, close to half of African American families (46 percent) experienced a period of unemployment, while just over one-third of white families did (34.6 percent).19 For African Americans, unemployment spells are more frequent, last longer, and end with new work at lower pay. African Americans, as well as Hispanics and immigrants, tend to be employed in sectors very sensitive to business cycles. When the general economy is doing poorly, populations concentrated in those sectors feel the effects more quickly and find that these effects last longer. The notion that working people of color are the last to be hired in a good economy and the first to be laid off when there’s a downturn carries much wisdom and empirical verification. Blacks with more precarious labor force attachments are indeed the last people to be hired as employers need more workers and are in fact disproportionately more likely to lose their jobs during slowdowns and recessions as the business cycle weakens.20

Because wages, benefits, and the likelihood of unemployment vary dramatically according to occupation and economic sector, occupational segregation is an important factor in why workers of color fare more poorly than whites. After taking educational attainment into account, seven out of every eight US occupations can be classified as racially segregated, according to one of the better studies of the issue. This study found that black men, for example, are represented proportionally to their share of the overall working population in only 13 percent of occupations. Black men are underrepresented in high-paying occupations and overrepresented in those with low wages. The average earnings of occupations in which black men are overrepresented is $37,005, compared with $50,333 in occupations in which they are underrepresented. Neither difference in skills nor in occupational interests fully explains occupational segregation, the study concluded, suggesting that the phenomenon is embedded in historic employment patterns.21

Sociologists often explain historic employment patterns as resulting from economic restructuring, focusing on blacks’ economic fortunes and emphasizing the rise and fall of the industrial economy and what industries and jobs they worked in. Historic employment patterns result partially from the shifting job structure as we moved from an industrial to a service economy. Data from the 1940s onward also suggest that political and institutional factors—the labor, civil rights, and women’s movements, government policies, unionization efforts, and public-employment patterns—have significantly influenced paycheck inequities. Additional nonmarket factors like racial discrimination have long shaped black economic fortunes powerfully. This discriminatory employment pattern is especially evident in the management and professional occupations.22

Despite laws, labor market discrimination persists as a major mechanism that maintains and extends occupational segregation. Some like to think that bias and discrimination are things of the past and play no part in inequality today, but research shows otherwise. In one experiment, researchers responded to help-wanted ads in two cities with resumes bearing either African American–or white-sounding names, then tracked the number of callbacks each resume received for job interviews. They sent out nearly 5,000 resumes for positions ranging from cashier and clerical worker to office and sales manager. Half of the applicants had names “remarkably common” among African Americans; the other half had white-sounding names, such as Emily Walsh or Greg Baker. All other qualifications listed on the resumes—work history, skills, and experience—were equivalent; the race-identifying names were the sole difference. The results indicated large racial differences in callback rates. Job applicants with African American names needed to send 50 percent more resumes to receive a callback, a statistically very significant gap. The researchers concluded that implicit bias among employers continues to shape employment prospects for whites and blacks.23

Other rigorous research examining the impact of incarceration on subsequent employment opportunities demonstrates the role played by the intersection of race and criminal justice. Black applicants with criminal records labor under a double burden—and given the racial inequities in the criminal justice system, black applicants are more likely to have such records. White men with criminal records had more positive responses to job applications than black men without them.24 Criminal records have a significant negative impact on job prospects for all applicants, reducing the likelihood of a callback or job offer by nearly 50 percent. However, the negative effect of a criminal conviction is substantially larger for blacks than for whites. This finding suggests that contemporary employment discrimination alone has an effect equivalent to a criminal conviction for black job seekers.25

The favoritism that white workers show toward other whites—especially in their search for good jobs that pay a living wage and that provide benefits—also reproduces racial inequality and occupational segregation. Want ads, websites, and public announcements are formal venues for job seekers, and most think that people find employment through them. A study of informal mechanisms in the workplace found that throughout their lives the majority of whites utilized social networks to learn about openings and find jobs, thereby protecting themselves from competition in the job market. Three-quarters of working men and 60 percent of working women said their social networks had given them a leg up in learning about a job opening and getting hired. Searching job ads played a minor part. This study built upon earlier research on social networks in employment, which showed that African Americans are less likely to obtain quality leads to employment from their networks relative to similarly situated whites.26 The power of informal social networks in helping people find jobs perpetuates existing racial inequity in the workplace.

Much has been accomplished in the years since major civil rights legislation of the 1960s opened new educational and occupational opportunities to African Americans, women, and others. African Americans have made tremendous strides in educational attainment and job performance, reaching the highest positions in virtually every occupation in America. Yet occupational segregation and labor market discrimination remain high, and they reproduce racial inequality in income and wealth. Without access for all to secure jobs that provide employment capital and wealth escalators, toxic inequality will continue to grow and to divide.

AFTER A LIFETIME OF WORK, WE ALL HOPE TO RETIRE SECURELY, comfortably, and with dignity. The security or insecurity of retirement depends not only on the cumulative earnings of one’s working life but also on one’s access to an employer-based pension or retirement savings plan. As the employment landscape renders working lives more unstable and fragmented, the goal of retirement becomes more problematic and contingent. Our interviews strongly suggest that retirement is becoming more and more an exclusively upper-middle-class notion. Many families we spoke to scoffed at the idea of retirement, telling us they would work until they could no longer do so, not until they choose not to. The Wards were one of these families.

Aaron and Felicia Ward, fifty-one and forty-nine, respectively, when we met with them in 2011, both worked most of their adult lives while sending several of their children to college. Felicia had stopped working when she was diagnosed with lupus. Aaron, a self-employed carpenter, also worked construction to supplement his income when his own business slowed down. The couple raised and legally adopted two of Felicia’s nieces because the girls’ biological mother was on drugs and could not care for them. The Wards contributed regularly to their church and to the Lupus Foundation, and they helped out other family members financially.

As we talked in their home in the Dorchester section of Boston, the atmosphere was friendly and spiced with self-deprecating yet enlightening humor. Toward the end of our conversation, we turned to their retirement plans. I asked if they had any retirement accounts or money put aside. “No,” Aaron jested, “I got some bottles downstairs. Cans and bottles. That’s our retirement. Bottles and cans. That’s our retirement; just stack them up in the basement.” I asked if they were thinking about when they might retire. Aaron jumped in, “What’s that [retirement]? You mean dying? Expiring?” Felicia added that she was already basically retired because she was not supposed to go back to work due to her illness. Aaron said, “I doubt if I’ll ever retire. I’ll have to hit the lottery in order to retire.”

The African American Ward family—joking about redeeming bottles stored in their basement and hoping their lottery number came up—presented a stark contrast to the white Ackerman family, with its $350,000 in retirement savings. But the dramatic differences in the two families’ retirement security did not result from individual behaviors and characteristics, like risk taking, deferring gratification, thrift, or superior financial decision making. Rather, they were the result of the jobs the Wards and the Ackermans had worked. Allison Ackerman had the good fortune to work in an economic sector that offered generous savings benefits at an institution that mandated and then matched contributions to a retirement account. The two families’ stories illustrate how deep structures shape well-being and create inequality along economic and racial lines. Differing work situations and differential access to employer-based benefits placed the Ackermans and Wards on two separate wealth-accumulation paths and shaped the futures they could contemplate for themselves. The ability to save for retirement is another crucial manifestation of the racial wealth gap and another important aspect of toxic inequality.

The federal Social Security program (1935) is the foundation of the retirement system in the United States, and from the very start it mirrored and locked in racial and gender inequalities that already existed in the working world. Coverage was far from universal because Congress excluded agricultural and domestic workers, affecting African Americans in the South the most, as two-thirds of them worked on farms or in domestic service. Thus the system started by including about half of the workforce. Those seniors today receiving Social Security far surpass the percentage receiving income from any other source. The amount a family is eligible to draw upon in retirement depends on what its members put in, which in turn depends on how long they worked and how stably, their pay levels, and whether the system included their occupation. Social Security provides widespread but not universal coverage; as of 2010, 14.4 percent of persons aged sixty-five or older were not receiving income from Social Security as they lacked sufficient paid and reported work histories to gain coverage. Most were late-arriving immigrants, infrequent workers, and noncovered workers. This excluded group was disproportionately female, Hispanic, less educated, newly arrived in the United States, and either never married or widowed.

Social Security provides slightly more than half (52.3 percent) of the income that sustains older couples and nearly three-quarters (73.8 percent) of the income that sustains older individuals. Over one in five couples and nearly half of single seniors rely on Social Security for the huge bulk—at least 90 percent—of their incomes. Nearly a third (31.5 percent) of African American single seniors rely entirely on Social Security for their income. Among Latino single seniors, 37.3 percent get all of their income from Social Security, whereas 25.5 percent of single Asian seniors depend entirely upon Social Security.27

Among typical recipients, benefits are modest: the median figure is $24,346 annually for married couples and $14,207 for singles. The figures suggest how Social Security was intended to provide only a foundation for retirement, not to fully resource the senior years after a lifetime of work. The legislation was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, and several times he publicly stated that workplace-based retirement plans and personal savings would supplement Social Security payments. The program aimed fundamentally to prevent impoverishment among the elderly who had worked most of their lives or their spouses or children. But although Social Security provides a modest source of economic security for seniors, employer plans and other savings fall far short of making this economic security truly robust. On average, only about half of the American workforce is enrolled in a pension plan. Although 57 percent of wage and salary employees aged twenty-five to sixty-four work for an employer that sponsors a retirement plan, only 48 percent actually participate in it. Access varies considerably depending on race. Some 62 percent of white workers have access to an employer-provided retirement plan, while only 54 percent of black and Asian employees do. Latinos fare even worse, with only 38 percent employed in firms that offer a retirement plan.28

Increasingly, employers are offering less reliable and riskier retirement plans. Defined benefit plans, which guarantee workers a specific income on retirement (often a percentage of their salary in their last years at work), are giving way to defined contribution plans, where the employee owns an account, like a 401(k). Pension coverage was never universal, but today less than half of workers (45 percent) have any type of pension provided by their employer.29 Whereas 62 percent of workers enrolled in a single retirement plan in 1983 had a defined benefit pension, by 2013, 71 percent of those enrolled in a single plan had defined contribution plans like 401(k)s. (Some workers—13 percent in 2013—held both types of plans.30) The transition from defined benefits to defined contributions significantly shifts the risk and financial burden of saving for retirement from employers to individual workers. Whereas defined benefit plans provide participants with steady payouts for as long as they live, defined contribution plans generally allow working people to take money out as needed or to purchase an annuity. This mean that retirees have to decide how much to draw upon during each year of their retirement. They face the risk of spending too quickly and outliving their resources or spending too conservatively, depriving themselves of necessities, and dying with money to spare.

Racial disparities in plan access are especially pronounced in the private sector. African Americans, Asians, and Latinos are respectively 15, 13, and 42 percent less likely than whites to have access to a job-based retirement plan in the private sector. (In the public sector, differences remain but are smaller.) Households of color lag behind white households in coverage by defined benefit pensions that guarantee lifetime retirement income; they are only two-thirds as likely as whites to hold such pensions. And when it comes to liquid retirement savings from defined contribution plans and other vehicles, the racial gap is growing wider. In 2013, white families had seven times more in retirement savings than African American families and eleven times more than Hispanic families. In 1989, white families had $25,000 more than African American and Hispanic families, and this disparity quadrupled to $100,000 in 2013. This gap is becoming more consequential as liquid retirement savings vehicles like 401(k)s replace traditional defined benefit pension plans.31

Generally, workers who enjoy higher earnings are likely to obtain more benefits. But access to benefits is also strongly associated with race; sociodemographic differences, employment context, occupation, and earnings alone cannot account for the entire gap in access to benefits between whites and Latinos and between whites and African Americans.32 Controlling for individual characteristics, African Americans’ and Latinos’ relative odds of obtaining benefits from employment are substantially lower than those of whites. Access to workplace-based benefits maps onto occupational segregation. African Americans, Asians, and particularly Latinos are less likely than whites to be employed in industries and occupations that provide high wages and workplace benefits, including retirement benefits.

These findings underscore the cumulative nature of economic and racial inequality and indicate rather strongly that measurements based only on earnings underestimate the actual magnitude of economic and racial disparity produced in the labor market.

Even for families like the Wards who are attempting to save for retirement, urgent necessities, unforeseen crises, and conflicting priorities can confound the best of intentions. Unemployment is more widespread, frequent, and longer lasting among workers of color. Necessity often requires tapping retirement accounts for daily needs, to pay bills, or to keep foreclosure or eviction at bay. Our interviews suggested, and national data confirm, that many American families, especially African Americans and Hispanics, treat retirement accounts as flexible, emergency cash reserves rather than as long-term savings vehicles. These employer-based accounts are often the only pots of money available to them in times of need. While part of the attraction of these assets for many people is their relative liquidity, these plans were not meant to function as lifeboats during periods of national economic hardship. When they are the only resources available, the result is a brutal choice between meeting expenses today and funding a secure retirement for tomorrow.

African Americans and Hispanics are especially likely to confront this choice. A 2012 survey of retirement plans found that about six in ten African Americans and Hispanics who lost their jobs because of layoffs or for other reasons cashed out their retirement savings plans entirely, compared to fewer than four in ten whites and Asian Americans.33 African Americans were also more than four times as likely as whites to take a hardship withdrawal from their retirement savings plans. Even when other contributing factors such as salary and age are held constant, African Americans are 276 percent and Hispanics are 47 percent more likely than whites to take hardship withdrawals for their immediate and extended families.34

Families of color often have different kinship obligations than white families. One key difference is the relative capacity for and priority of helping family members in times of need in relation to saving for retirement. In a survey of 19,000 employees at sixty of America’s largest corporations, 36 percent of African American employees and 38 percent of Hispanics (compared with 24 percent of whites and 21 percent of Asian Americans) said that they had more pressing financial priorities and did not prioritize saving for retirement. Those other priorities, as our family interviews revealed, often included helping members in the larger familial network. In our interviews, white families disclosed a broad pattern of receiving financial assistance from other family members in times of need, perhaps mitigating the need to borrow, load expenses onto credit cards, or drain money from accounts dedicated to retirement or college. In contrast, successful African American families in particular were called upon far more often than their white counterparts to provide help to kin. We heard this time and time again. It is enormously beneficial to have extended family members who are financially more successful, especially if they are willing to help in times of need or to assist in taking advantage of an opportunity. Our family interviews mirror large survey data showing that college-educated black households provided financial support to their parents three times more often compared to white college-educated households.35 Extended family members with few resources are simply not in a position to help, which is often the case for blacks. Felicia Ward’s personal experience is exemplary. She told us, “I can’t go to my family for nothing as far as help financially, because they got their own problems.”

THE ACKERMANS, THE MEDINAS, AND THE WARDS LIVE VERY different lives, enjoy very different degrees of economic security, and see very different futures for themselves and their young adult children. Their lives suggest the vast inequities that result when only some people have secure jobs in stable economic sectors with ample benefits, including employer-matched retirement accounts and college tuition assistance, and others, disproportionately people of color, have lower-paying work in sectors more susceptible to business cycles, in jobs providing few benefits, little access to retirement accounts, and no help in making college more affordable. The great differences in family wealth and well-being that result from employment are a crucial source of toxic inequality.

New York Times columnist David Brooks asks three questions that he suggests account for success or failure in life. Are you living for short-term pleasure or long-term good? Are you living for yourself or for your children? Do you have the freedom of self-control, or are you in bondage to your desires?36 Whether or not one thinks these are the right questions to ask, one thing is abundantly clear: the Ackermans and Medinas live their lives by the same answers, but without substantial changes to our contemporary employment landscape, the worlds of Peter Ackerman and Tina Medina will only grow further apart.

As important as it is, transforming the employment landscape is not the only change needed. In our 1998 conversation, Kendrick Johnson, whom we met in Chapter 1, posed a very different question about success in life. As a highly successful professional, he described driving to work every day through affluent suburbs and asking himself the same question: “I’m driving to work from Orange County, Laguna, Newport, and I’m looking at these houses and saying, ‘What are these people doing for a living, and how come I’m not doing it?’” In Chapter 4 we meet individuals who live in those kinds of communities, and we answer Kendrick’s question about what those families have that his doesn’t: an inheritance.