“I remember being in Stiff’s offices and saying to them that Ian was fantastic and asking what he was doing and they said, ‘He’s got a solo career, he’s writing songs – there he is now.’ And there was this bloke shambling along the street with a shopping bag and wearing a mac and a pair of kickers.”

– Wreckless Eric

Out of the searing summer heat of 1976, Stiff Records emerged to launch an assault on what had become a complacent and yawningly predictable record industry. Impeccably timed, coinciding as it did with the detonation of the incendiary device which punk placed under the British popular music scene, it defied all the rules and would change the face of the singles market through imaginative sales devices and gimmicks. Stiff would also become a launch pad for dozens of artists and bands who might otherwise have remained on the margins or simply never cashed in their 15 minutes of fame. Executives at the major record companies looked on open-mouthed as Stiff launched itself amid a barrage of self-deprecating slogans such as ‘If They’re Dead We’ll Sign ‘Em’ and ‘If It Ain’t Stiff, It Ain’t Worth a Fuck’. A ‘stiff’ in the music industry was a flop, a dud, a turkey, yet here was a label promoting itself as the very antithesis of established practice in the record industry.

But while the majors sniggered at such impudent enterprise, Stiff was to pull off a coup that few could have forecast. Young bands were plugging in their practice amps in bedrooms, garages and rehearsal rooms in every corner of Britain and punk was fast taking hold. Venues in the capital were packed to the rafters every night, often with three or four bands on the bill. While the pub rock acts that had provided a badly needed alternative to the glam bands were, in the main, disenchanted musos of the old school, the bands and artists now emerging were younger and far more shameful in their contempt of professional musos. And in Stiff and labels like it, they had resourceful champions with identical attitudes.

Stiff was not the UK’s first independent label. Strictly speaking, older labels like Track, Charisma and Virgin were independent, as were more recent labels like Oval (established by Charlie Gillett and Gordon Nelki) and Chiswick. But its founders Dave Robinson and Andrew Jakeman, alias Jake Riviera, were resolute in one regard – they were going to take on the major labels at their own game.

“I was aware that something would have to happen because the record business was in a middle-of-the-road kind of trough and I think that it had been like that for about two or three years,” said Dave Robinson in the Radio 1 documentary From Punk To Present.10 “It was like a real kind of ‘business music’ era and it was a bit boring; it was certainly boring to be young. It was a time your mother actually did like, with all the Elton Johns and such like.”

The seeds of Stiff Records were sown in the United States in 1974 while Jake was on tour with Dr Feelgood, the Canvey Island pub rock band he was then managing. He had discovered a number of small indigenous labels featuring local bands – Flat Out and Berserkly Records in San Francisco being prime examples – as he travelled around the country. This enterprising climate meant that aspiring groups were being played on local radio stations and then being picked up for nationwide distribution by larger record labels. By the time Jake and Dr Feelgood returned to England, he was buzzing with ideas for his own label and had even started dreaming up logos.

A former advertising executive from Pinner, west London, with a sharp line in cowboy boots and a vicious temper, Jake was an arrogant operator with aspirations to become an A&R man. Prior to his stewardship of the Feelgoods, he had managed pub rock stalwarts Chilli Willi & The Red Hot Peppers, whose debut album was released on the obscure Revelation label. When this label folded, the larger-than-life salesman got the band signed to Mooncrest Records (an offshoot of Charisma) and they released the more successful Bongos Over Balham. In July 1976, Jake began plotting his own label in collusion with Dave Robinson, the then manager of both Ian Dury and Graham Parker and who had built up an extensive archive of live concerts recorded at the Hope & Anchor in Islington. Their game plan was simple: to create an outlet for the groups on the pub scene who had long been overlooked and to give some of the industry’s misfits a chance.

“I was very frustrated being a manager in those days,” Dave Robinson told the author in an interview for Hot Press magazine in 1996.11 “The major labels were very pedantic, like they are now, and convinced that they were running the record business. So if you wanted any special marketing deal, or to do something off the beaten track, they didn’t want to do it and it was going to cost money. Graham Parker was at Phonogram and we were having enormous live acceptance of him and his band. The records were good and we were doing okay, but we couldn’t get onto first base in America, and nobody wanted to know Ian Dury. The major record companies just thought it was pub music – old R&B.”

He continued: “The idea of Stiff was to be a conduit for people who could not find the music business any other way. My theory was that there’s an Elvis Presley out there, but he’s working in a factory in Coventry and he doesn’t know how to get in touch with me. The best artists are out there, but they don’t know how to connect with the music business, because it doesn’t tell you that. If you go to a couple of majors, they’ll put you off for life. You will sit in reception, nobody will see you, eventually some junior will come down and take a tape off you and you’ll never hear from them again. How does anybody know what’s going to be the next anything that’s great simply by the clothing you wear?”

Even before this juncture, Dr Feelgood had been central to a plan which had highlighted the need for independent labels. Musicians from the popular R&B band, had joined with Nick Lowe of Brinsley Schwarz and Martin Stone of The Pink Fairies to form a band which gloried under the name Spick Ace & The Blue Sharks. This ad hoc ensemble had planned to record an EP for Skydog in Holland, but contractual difficulties meant it never happened. Numerous attempts by Jake to interest record companies in Nick Lowe – who had secured his release from United Artists – had also come to nothing.

“I spent years shouting at people over desks in record company offices. They turned down virtually every idea I had,” Jake later told Melody Makers Allan Jones. The only route left was to set up his own label and in the summer of 1976 Jake borrowed £400 from Dr Feelgood and he and Dave Robinson formed Stiff. In a coincidence which was to prove highly fortuitous for Ian, Stiff rented the ground floor of 32 Alexander Street from his management company, Blackhill Enterprises.

Undeterred by repeated failed attempts to get Nick Lowe a record deal, Jake and Dave despatched Nick to a recording studio with only £45 to spend. The shoestring budget didn’t affect the quality. Nick, accompanied only by drummer Steve Goulding of The Rumour, recorded ‘So It Goes’ and ‘Heart of The City’ – two devastating songs of less than two and a half minutes each. Excited by the raw quality and immediacy of these songs, Jake and Dave rushed to a pressing plant and on August 14, 1976, a single was released as Stiff Buy 1. The record, produced jointly by Nick and Dave, was sold mainly via mail-order from Alexander Street. But in contrast to the tatty decor at base camp, the record’s packaging was slick and featured the kind of sharp-witted one-liners that would become Stiff’s hallmark. Curious messages, ‘Earthlings Awake’ and ‘Three Chord Trick, Yen’, were scratched into the matrix (the smooth bit between the groove and the centre). A distinctive black record bag carried the phrases ‘If It Means Everything To Everyone … It Must Be A Stiff and ‘Today’s Sound Today’. The record itself carried the messages ‘Mono-enhanced STEREO, play loud’ and ‘The world’s most flexible record label’. This was a whole new approach.

Nick told Melody Makers Caroline Coon: “It’s a sound that’s happening now. Clever words over a simple rhythm. Basically, I’ll do anything. I can write in any style, but all my friends have become punks overnight and I’m a great bandwagon climber.”

‘So It Goes’ didn’t get near the Top 40, but the music press gave it and its flip-side a warm reception and Jake and Dave found it impossible to keep it in pressings as demand grew. Suddenly, they had found a hole in the market and Stiff’s cramped office was alive with activity as they drew up a list of exciting artists to fill it. As word of the maverick label got around, there was no shortage of hopefuls calling at its door and Stiff had an open-house policy.

Nick Lowe set up shop at Pathway Studios in London and sat and waited to see who Dave and Jake would send along. Drummer Steve Goulding was on stand-by to accompany those who showed up and Nick recorded their rough and ready songs using an eight-track.

“Almost any nut-case who had a bit of front would get a try out at one time from Stiff, pretty much, until it got completely out of hand,” said Nick.10 “But for a while they were the best people around, those people that none of the other record labels would touch. They had genuine front, which used to scare proper sensible record companies. It wasn’t musically on the case, but I think I had the attitude of the artist on the record.”

Singles started coming thick and fast from Alexander Street and Stiff’s inventive marketing ruses made sure they were eye-catching. The Pink Fairies, fronted by long-haired rocker Larry Wallis, provided the label’s second 45 ‘Between The Lines’ before being signed by Polydor. It was followed by the more laid-back ‘All Aboard’ by US group Roogalator, which was delivered in Sixties-style 33-and-a-third rpm. ‘Styrofoam’ by Tyla Gang, led by the growling pub rocker Sean Tyla, and ‘Boogie On The Street’ by Lew Lewis & His Band followed as Stiff gathered momentum. ‘Artistic breakthrough! Double B-side’ was stamped on the plain white sleeve of ‘Styrofoam’ with a guarantee that ‘This record certified gold on leaving the studio’. The cover for Roogalator’s début was a blatant parody of With The Beatles and when EMI complained about the use of the Emitex advert and trademark, the record was withdrawn and deleted. Stiff continued to use mail order and peddled some copies through a handful of independent outlets.

Stiff’s sixth single was The Damned’s ‘New Rose’ – the first British punk record. Dave Vanian, Captain Sensible, Brian James and Rat Scabies had recorded their raucous anthem in a drunken state at Pathway along with a shambolic rendition of The Beatles’ 1965 hit ‘Help!’ as a B-side. ‘New Rose’ didn’t make the Top 40, but it was an underground success and Stiff had to get United Artists to help out with the distribution. Not only was Stiff shaking the singles market into life with their picture covers, coloured vinyl and other novelties. It was also at the forefront of the biggest revolution in popular music for years.

Adding to the label’s anti-establishment credibility, Jake verbally abused journalists, once famously yelling down the phone, “I’m not interested that you’re interested” and Stiff’s equally arrogant approach to distribution left some radio presenters aghast.

“I remember reading this massive article in New Musical Express about Stiff Records and I thought where are these records, I’m getting 60 records a week through the mail, why haven’t I got these?” DJ Johnnie Walker recalled.10 “So I rang up NME and asked how I could get hold of Jake Riviera and they gave me the number. So I rang him up and he said: ‘Oh, you want the records, can you come down for ’em, this is where we are.’ I was on Radio One at that time and I thought this is great, this is a really different way of doing things, because most of the record companies beat a path to your door and here was somebody saying, ‘Well, if you want these you’re gonna have to come and get ’em.’ Jake’s idea was right – ‘I’ll make these records for £30 each, I won’t sign these blokes up, we’ll just make the records, stick them in the back of the car, drive round a few record shops and sell them out the back of the car.’”

At 40 Oval Mansions, meanwhile, the Dury-Jankel partnership was flourishing. Although the fruits of their labour would not be presented to the public for almost a year, they would go on to have a profound effect on everyone who heard them. Chaz Jankel arrived each morning at Ian’s Vauxhall flat with his Wurlitzer electric piano and acoustic guitar. Ian would disappear into the kitchen to make some coffee and then present Chaz with sheets of lyrics which he had copied out on his old typewriter. With a cardboard cut-out of Gene Vincent in Ian’s sitting room for inspiration and Taj Mahal records playing in the background, the two chatted and experimented with this untested material.

In some aspects, the two men were very different. Ian was 34, had worked as a teacher and had two children from a failed marriage to support. He spoke in a harsh Cockney accent and had an abrasive manner. Chaz was still in his early twenties, single, and was softly spoken by comparison. But both were perfectionists and took a methodical, almost scientific, approach to songwriting. Ian laboured for hours on his lyrics, honing them and searching for a better rhyme or hook. Chaz, meanwhile, had the patience to work with the demanding songwriter and search for a suitable tune and rhythm, even when he had reservations as to the potential of some of Ian’s eccentric lyrics.

“Ian would put some type-written lyrics in front of me and I would start going through them,” says Chaz. “As soon as I got to one I liked I would say, ‘Yeah’ and I would start trying something out. There was this one which always used to crop up called ‘Sex & Drugs & Rock’n’Roll’ and any time I got to it I said, ‘Naah, we all know about that, why write about it? It’s obvious isn’t it?’ The next day I would arrive and it would be there at the top of the pile and he would keep trying to sell it to me. I couldn’t think of anything for it and one day Ian came in and started singing this riff and singing ‘Sex and Drugs and Rock’n’Roll’. I said, ‘Bloody hell, that’s good’, because Ian didn’t often initiate musical ideas. He was a lyricist and needed a melody and I was a musician who needed a lyricist. I was astounded at the fact that he could come up with this song and so then I wrote a lead section for it and we knocked it together.

“Later on, I was at his flat and he put on an Ornette Coleman record called ‘Change Of The Century’ with Charlie Haden and Don Cherry on it, and went into the kitchen to make some coffee. I was listening and probably looking at another lyric and suddenly, about a minute into the record, I heard this bass riff and I thought ‘hang on a moment’. As I looked up, Ian was standing in the doorway grinning from ear to ear and I said, ‘You sod’. Then Ian had this fit of conscience and thought he had to do something about it, so he wrote to Don Cherry and he sent back a card saying, ‘This is not my music, you’re fine’, meaning that music comes around and goes around and is there to share.”

A few years later, Ian made a further confession to the bass player himself, according to Terry Day. Ian and Terry went to see Charlie Haden, drummer Eddie Blackwell, Don Cherry, and an alto sax player, at the Hammersmith Odeon and, afterwards, they ventured back stage. Ian was just about to approach Charlie as he came out of his dressing room carrying his double bass when he spotted Ian and told him: “‘My daughter really digs you and your music’ Ian thanked him and then tells him about nicking two bars or so from his bass line and it being part of the music of ‘Sex & Drugs’. But Charlie replied, ‘Well, that’s the name of the game – what’s new?’” recalls Terry.

Chaz’s fondness for funk brought a dimension to the songwriting process which had not been present in Ian’s collaborations with either Russell or Rod. Compared to the rock’n’Roll or blues rhythms that had carried many of the Kilburns’ songs, the young musician’s funk and jazz influences created a very different environment for Ian’s words. Charlie Hart had also been a fan of funk groups and ‘Billy Bentley’, which he co-wrote with Ian, gives a brief glimpse of his influences. But, to Charlie’s disappointment, his input was rarely welcome and the tunes written by Russell and Rod had mostly relied on more standard rock rhythms. Now, there was a very distinct change of direction.

Chaz: “There was a lot more syncopation in the sort of music I liked; you could say it was more southern hemisphere and less urban. But to say that was my only influence would be wrong. I was into bands like Free, Jeff Beck and Deep Purple, but when The Beatles made Sergeant Pepper and most of the world was bowing down and kissing their feet, I didn’t like it, because it was nothing to do with a small group any more and the lovely little songs they could knock together. I was looking further afield for more bluesy, gutsy raw material and in a way, that is where Ian and I are very similar. He loves it raw and real and he loves good country music and jazz. I have spent many an hour listening to music with him.

“I think I can safely say that Ian introduced me to Bill Evans who is possibly the finest pianist this century. I think he felt a bit concerned about having a jazz group, because he didn’t feel it was good enough and that he didn’t feel he had the ability to sing jazz.”

Chaz recalls one moment during these sessions at Ian’s when a different set of ground rules regarding the rhythms they would use first emerged. “White music was based more on melody and chord changes and I was coming from a slightly different angle. In ‘Wake Up And Make Love To Me’, I was a bit concerned as I had been through 16 bars on the same chord and I hadn’t changed and usually by this point Ian would be saying, ‘When does it change?’ One of Ian’s friends, Smart Mart (Martin Cole), had a girlfriend from South America and one day she was round at Ian’s. She was listening to the song and she said to us, ‘Why does it have to change?’ and we said, ‘Oh yeah’ and that was the first real experiment of letting the rhythm build itself and building layers of melody on top of that. Lyrically, it was a very sensual song and lead singers have to be very careful about doing that in front of a male band when they go out live, otherwise you fall into the Barry White camp. But Ian always pulled it off. Since then, every gig we have ever played together as The Blockheads has opened with ‘Wake Up’.”

Chaz was not the only musician with whom Ian was collaborating at this time and this, too, would help develop the multi-faceted songbook which was taking shape. Ian was also presenting sheets of lyrics to American journalist and guitar player Steve Nugent and they would work on material into the evening together at Steve’s flat in Parliament Hill Fields, Hampstead, north London. Ironically, his American friend would compose the music for some of Ian’s most ‘English’ and best-loved songs. Steve was born in Newhaven, Connecticut, in 1950, moved to England in 1972 to take up a PhD at the London School of Economics and had written articles for the small music magazine Let It Rock. Lapping up the London pub rock scene he found on arrival, he had been captivated by a Kilburn & The High Roads show at the Tally Ho and had spoken with Ian at a couple of subsequent gigs. Steve had also interviewed Ian for the magazine one afternoon in Wingrave.

Steve recalls of this early encounter: “He is a power freak, so he checks people out very carefully and tries to get them in a place and keep them there. He was naive as a rock performer. He had finally dumped painting and illustrating and he was going to be a public person and I really had no experience of being a music journalist, so it was a meeting of the naive. He was in the course of developing his public persona and he was much less convinced of his central position in the universe than he was a few years later.”

Steve left England for Brazil in 1974, but returned two years later and rejoined Ian at Catshit Mansions. Ian, who at one stage had considered taking a job as a lift attendant at Harrods, told him of the Kilburns’ demise and of his new publishing deal with Blackhill and invited him to help write a few songs. He agreed, Blackhill gave him an advance of £25, and out of their writing sessions came six songs. One of these was ‘Billericay Dickie’. A boastful account of sordid sexual conquests on the back seats of cars, it was narrated by an unreconstructed Essex plasterer in full Cockney colour and was set to a jaunty fairground tune. It was a prime example of Ian’s clever use of rhyme and the portrayal of the seedy side of life through fictional characters.

Steve, who is now a Doctor of Anthropology at Goldsmith College, London, says of the now famous song: “‘Billericay Dickie’ has big chords and is carried by the words more than the music. The lyrics were very funny to me and they seemed to be describing a kind of Englishness that I knew very little about. But it had a ring of authenticity in the way it was presented by him. That was in the text, as it were, and it was really more a matter of writing a simple vehicle to allow the words to get across. It was not very complicated.”

The lyrics for ‘Plaistow Patricia’ – a no-holds-barred tale of heroin-addiction – was also in the batch of song ideas shown to the quietly spoken American student. Ian had once again coupled a fictional character and an Essex address to devastating effect and Steve completed the picture with a jarring guitar intro and a fast-paced, aggressive rhythm. “It’s a sort of travel tune. It’s about the nether regions of inner London, that bit out there which is always geographically unspecified,” says Steve.

Of the uncompromisingly stark images Ian was creating, he adds: “There was a much more literary take on the album compared with punk. To me, it was coming out of beat culture and noir culture and hard world thrillers, it had nothing to do with punk at all.”

In the spring of 1977, Ian and Chaz decided to record some demos of the songs and were advised to try Alvic, a small studio in Wimbledon run by two men known as Al and Vic. Chaz played the bass, piano and guitar parts, while Ian sang and knocked out a basic drum beat. In spite of the paralysis of the left side of his body, Ian was extremely rhythmic and could keep a solid beat by using his right arm to hit the snare and his right foot to play the bass drum. The recordings which resulted sounded spartan, but they confirmed the potential of the material that had been building since the break-up of the Kilburns. Steve also went to Alvic to help work on the songs which they had originally recorded on a small cassette recorder: ‘Billericay Dickie’, ‘Plaistow Patricia’, ‘My Old Man’, ‘Blackmail Man’, ‘Wifey’ and another song, the title of which Steve cannot now recall.

During a session one day, the studio engineer told Ian of a great rhythm section who were also doing session work there and suggested that he check them out. It was a red hot tip.

Drummer Charley Charles and bass player Norman Watt-Roy were members of a band called Loving Awareness, but this ‘concept’ group had begun to lose its way and they were hiring themselves out for session work. Both were seasoned musicians and although they were unknown to Ian, they were top drawer.

Norman was born in February 1951 in Bombay, where his Anglo-Indian parents were stationed with the RAF. In November 1954, seven years after India gained independence, the Watt-Roys moved to England, with three-year-old Norman and his older brother and sister. He went to St Joan of Arc Primary School in Blackstock Road, Highbury, north London, where the family initially lived, before attending secondary school in Harlow, Essex. He studied art briefly at Harlow Technical College when he left school at 15. But it was in music, his first love, that he would build his life.

When he was about 10 years old, Norman had been shown some guitar chords by his father and from this early tuition he had learned to play by ear, playing in school bands alongside his brother Garth, who played lead guitar. When he was 15, he developed a passion for bass guitar and never looked back. A teenage friend who had a job was so keen to join the boys’ band that he offered to buy a Top Twenty bass and a bass amp and Norman agreed to teach him the rudiments. When his pupil’s blistering fingers caused him to throw in the towel, he donated his bass and equipment and Norman took over. At 16, Norman went off with Garth to tour Germany with show-bands and started to make a living. In the mid to late Sixties, he made his first recordings in a four-piece group called The Living Daylights, again playing alongside his brother. A single and an EP were released before the project fizzled out and in 1968 the Watt-Roys joined The Greatest Show On Earth, a nine-piece soul band with a black New Orleans singer, Ozzie Lane. When Ozzie later returned to the US and was replaced by Colin Horton-Jennings, the band signed with the Harvest label and made two albums, Horizons and The Going’s Easy. The other members of The Greatest Show On Earth were Ron Prudence (drums), Dick Hanson (trumpet) – later with Graham Parker – Tex Philpotts (sax), Mick Deacon (keyboards), who later joined fifties retro band Darts, and Ian Aitcheson (sax).

The group folded in 1971 and Norman joined Mick Travis, Stewart Francis and Graham Maitland to form Glencoe. A solid rock band, Glencoe recorded an eponymous album and another called The Spirit Of Glencoe although they made only a minimal impact during the two years they were together. In early 1972, young guitarist John Turnbull had joined from singer Graham Bell’s band Bell & Arc and when Glencoe split two years later, John and Norman remained together.

Since leaving school in his native Newcastle, Johnny had earned a living as a musician and he struck up a close friendship with keyboard player and fellow Geordie Mickey Gallagher. “Since I was a kid, music was all I could think of and I used to watch my uncle playing this huge Gretch guitar that I could hardly get my hand around,” says Johnny. “I just wanted to play. I was banging on biscuit tins with knitting needles and during Friday Night Is Music Night I would be dancing on the lino. When my parents got me a toy guitar, I went outside and learned ‘Peggy Sue’ straight away and then I came back in and played it and they said, ‘Oh we’d better get him a proper one.’ Later on, I had my own little band in the clubs and I was working in a tailor’s and then my old school friend Colin Gibson got together with Mickey in The Chosen Few and told Mickey about me. When Alan Hull left that band to do a solo album, I became a member of The Chosen Few with Mickey, Graham Bell, Colin Gibson and Tommy Jackman. We got a trial for colour television through Brian Epstein down here and Jimmy Savile and it was a disaster because we wore the wrong suits, but out of that we got gigs at The Marquee through Alan Isenberg and Don Arden. When we got a residency, we had to move down to London.”

Mickey had worked for the Ministry of Pensions and National Insurance for a year after leaving school, but quickly abandoned the civil service and began playing the CIU working men’s clubs in Newcastle with local group The Wayfarers. A versatile keyboard player, he was always in demand and had appeared in a string of groups by the time he joined The Chosen Few. At one stage in the mid-Sixties, he deputised for Newcastle band The Animals in between Alan Price’s premature exit and the arrival of Dave Rowberry. Mickey played dates in Scandinavia and the UK with the group – the first hit act produced by Mickie Most and the first British band to top the US chart after The Beatles.

In the spring of 1966, Mickey, Johnny Graham, Tommy and Colin, formed a new group, Skip Bifferty, and released one album on RCA in September 1968. Subsequently, they became Heavy Jelly and recorded a single for Island before parting company towards the end of 1969. Following the collapse of this project, Bell joined Every Which Way, led by Brian Davison, the former drummer with The Nice, and Johnny and Mickey were recruited by Robbins Music as songwriters. To provide an outlet for their material, they briefly established Arc with Tommy Duffy on bass and Rob Tait on drums (later replaced by Dave Trudex), before reuniting with Bell in Bell & Arc.

Johnny and Mickey went their separate ways for the first time when Johnny joined Glencoe and Mickey became a member of Parrish & Gurvitz and subsequently Frampton’s Camel, led by Peter Frampton. But following the break-up of Glencoe in early 1974, they were reunited, this time with Norman Watt-Roy, in a group which would have more influence on Ian’s career than any other.

Loving Awareness was the brainchild of Radio Caroline pioneer Ronan O’Rahilly, but the group was slow to get off the ground and had taken some time to settle on a permanent drummer. Simon Phillips was initially involved, but he was committed to sessions for a Frank Zappa album and when he left, a string of other drummers were tried, including Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Artimus Pyle. But it was while watching television one night that Norman stumbled on Charley Charles, the man who would complete the rhythm section and later become such a powerful and solid force behind Ian.

Norman remembers: “I was sitting at home watching The Old Grey Whistle Test with my dad and Link Wray was on and he had this guy playing drums who was wicked. My dad said, ‘That’s the kind of drummer you want’ and I said, ‘Yeah, yeah.’ I rang up our manager and he’d seen The Old Grey Whistle Test and I said, ‘They’re in England touring, let’s ring him up, he’s probably American.’ They were in Manchester or somewhere that night and we rang Charley up and he was living in Tooting and he was only doing session work for Link Wray. After the tour, Link Wray was going back to America, but Charley wasn’t doing anything, so he was up for it. We got him down and Simon was there that night and for that night we had Simon and Charley on drums. But even Simon said to us afterwards, ‘That’s your drummer, isn’t it.’ Charley was so solid, and what a lovely bloke. He was just lovely, completely off the wall and his ideas were so mad.”

Curiously, Link Wray, whose real name was Ray Vernon, hailed from Norfolk, Virginia – the birthplace of Gene Vincent – and had played on some of the same country shows as Ian’s hero in the mid-fifties before changing his name to Link Wray and recording a series of atmospheric instrumentals, notably ‘Rumble’. Whether it was fate or simply good fortune, it was through the musician from Vincent’s home town that anonymous session man Charley Charles had come to the attention of Norman, Mickey and Johnny.

Charley was born in Georgetown, Guyana, where his father Tom was a big band leader. He moved to London with his family at the age of 13 and later attended Wandsworth Technical College. After working for a couple of years at the Woolworth store in Whitechapel, he joined the Army and was posted to Germany and later Singapore where he drummed with various groups. When disillusionment with the military set in, he bought himself out in 1969 and toured the Far East with eight-piece band No Sweat. On his return to London in 1972, Charley was in great demand and backed artists including Kala, Arthur Brown, Arthur Conley, Casablanca and Link Wray, before he was invited to join Loving Awareness.

The group rehearsed intensely before flying out to Palm Springs, California, where they spent six weeks recording an album. The self-titled record was distributed by Phonogram in Holland, but after only 17 gigs back in the UK, Johnny broke a bone in his hand. Loving Awareness lost its momentum and the four musicians began doing session work.

Mickey: “It was called Loving Awareness and was all about love power and all that sort of stuff. Ronan’s theory was that everybody lives from a position of defensive awareness and the only way to change it was getting people to live a loving awareness type of life. That was all great, fair enough, and then punk happened!”

Johnny: “Loving Awareness wasn’t that successful and monetarily we had to do sessions, so we did all sorts of things. Me, Charley, Mickey and Norman did sessions with Lulu and this guy called Adrian Gurvitz. We did work for various people in studios and sometimes people heard about you. It was great if we could get sessions as a band, but then sometimes people just wanted a rhythm section. So Charley and Norman started getting bits of work with people and one of them was Ian.”

Norman and Charley immediately gelled with Ian and Chaz at Alvic Studios and completed the demos within about a week. The following week, they began recording the album itself at The Workhouse Studio in the Old Kent Road. Blackhill owned a 50 per cent share in the studio and Manfred Mann held the remaining 50 per cent, and it was agreed that Ian, Chaz, Norman and Charley would record songs in “dead time,” when the studio was empty. Blackhill stumped up about £4,000 to pay for the projected album which was produced by Pete Jenner, Laurie Latham and Rick Walton. Pete had previously produced records for Kevin Ayres, Roy Harper and Mike Oldfield among others, but Laurie and Rick were younger and had little or no previous experience of production at this point.

A chance remark made during one of these sessions at The Workhouse would have great significance for Ian. Chaz remembers: “We were listening to the playback of a song Ian and I had written called ‘Blockheads’ and Charley was looking at the lyric and he got to the line which says, “You must have seen parties of blockheads … with shoes like dead pigs’ noses”. He glanced down at his footwear and he had boots that resembled dead pigs’ noses and he said, “Ere Ian, that’s me’ and Ian changed one word in the lyric from ‘You’re all blockheads too’ to ‘We’re all blockheads too’. To say that we’re all stupid was better than saying you’re all stupid.” Charley’s off-the-cuff remark was not forgotten.

Ex-Kilburns Davey Payne and Ed Speight were invited to help fill out the sound with sax and ‘ballad guitar’, while jazz pianist Geoff Castle, a friend of Ed’s, played Moog synthesiser on ‘Wake Up And Make Love With Me’. As these recording sessions progressed, it was obvious that the songs which Ian had been working on with Chaz and Steve respectively – a heady mixture of funk rhythms, Cockney language and urban stories – made for a unique package. Ian’s coarse and untrained vocals clearly provided the perfect narration for these stories but even more crucial to the feel of the music was Ian’s conscious decision to sing with a pronounced English accent.

“Ian wasn’t afraid to speak the truth,” says Chaz. “If he was angry about something he’d find a way of venting that spleen through his lyrics. That is what attracted me to Ian, because I had worked with a few different lyricists, but nobody who was as broad as Ian and tapping into his native England like he did. A lot of singers, including myself, were still putting ‘baby’ an awful lot in the songs and singing in an American accent. When we finally got to record ‘Wake Up And Make Love With Me’, Ian sang it in an American accent and somebody [Charlie Gillett] said, ‘Hey, you sound like Barry White’ and that really nailed it for him. He thought, ‘Why try and do that?’ You can slur it a little bit, you can give some of those nasty vowels a little bit of assistance, but it wasn’t like we came from Liverpool. It was what Ian found colourful and it was what Ian chose to identify with. I think a lot of people do it subconsciously, we all did it in our teens, but Ian somehow allied himself with Cockneys – people who had drawn the short straw.”

Of the completed album, Ian said:8 “Some of the songs had been five years in the making, while some had come out real quick. There was a sort of pressure because lots of people without any talent were getting extremely famous and I was getting the hump. I was ultra jealous. But in many ways it was easy writing like that because nobody had heard of me. I was getting quite angry I’d been working hard and not succeeding for six years.”

Stiff had by now launched a plethora of new acts and was the power house behind an energised singles market. Punk band The Damned, Television bassist and vocalist Richard Hell and heavy metal band Motorhead were among those it had given a leg-up. But it wasn’t just interested in selling records to the growing punk market. The label’s 12th single release, Max Wall’s interpretation of Ian’s whimsical ‘England’s Glory’ (produced by Dave Edmunds) was a typical Stiff single, insofar as it was the kind of record that major record companies would have dismissed out of hand. Commercially, the ageing comedian’s outing on Stiff was a flop and most copies had to be given away with Hits Greatest Stiffs, a compilation album containing songs from its earliest 45s released towards the end of 1977. But Dave and Jake’s willingness to give idiosyncratic, but nevertheless talented, songwriters, a start was best exemplified by the issue of ‘Less Than Zero’, the record which first introduced Britain to Elvis Costello.

Born Declan Patrick McManus, the gangly, bespectacled singer had first played his own songs live in 1972 as a long-haired teenager in Rusty, a folk rock group based in his native Merseyside. The following year, he was playing solo and had adopted his mother’s Irish maiden name, Costello, and after moving to London, he established his own bluegrass group Flip City. At 19, he was married, living in Whitton, Middlesex, and working by day as a computer operator at the Elizabeth Arden cosmetics company in Acton (the ‘vanity factory’ in his song ‘I’m Not Angry’). Skinny, spotty and with thick rimmed glasses, Costello looked every bit the nerd, but all the time he was bombarding record companies with tapes and when he got no response, he camped in their lobbies with a guitar and started playing. His persistence was eventually rewarded when, on August 15, 1976, his demos were played on Charlie Gillett’s Sunday night radio show Honky Tonk. But it was a tape he sent to Stiff on the foot of an advertisement for new artists (the tape later emerged as a bootleg album entitled, in a parody of an Elvis Presley LP, 5,000,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong) which finally broke the deadlock for the precocious singer-songwriter.

“The tape was actually the very first tape we received at Stiff,” Jake told NME’s Nick Kent in August 1977. “I immediately put it on and thought, ‘God, this is fuckin’ good, but at the same time I was hesitating because, after all, it was the first tape and I wanted to get a better perspective.” Jake subsequently wrote to D.P. Costello, asking him to be patient while he listened his way through the other demos which were arriving, but after receiving what he described as “a load of real dross in the mail,” he agreed to sign him. In a west London bar, Jake christened him ‘Elvis Costello’, a move which caused some offence when, on August 16, 1977, Elvis Presley died at his Graceland mansion aged 42. This was just weeks after the release of the English Elvis’s debut My Aim Is True on which the words ‘Elvis Is King’ were written into the chequered sleeve pattern. The timing of Costello’s debut simply exacerbated the controversy, but the storm passed and the record went on to be a hit. Although his first three singles ‘Less Than Zero’, ‘Red Shoes’ and ‘Alison’ did not chart, much of the energies of those at Stiff were being devoted to their rising star during that summer.

Meanwhile, Stiff’s cramped headquarters had become a giant sitting room for artists on the label and assorted unsigned musicians who, like Costello, had turned up looking for a break. One such hopeful was Eric Goulden. The baby-faced singer had arrived in London with empty pockets after leaving Hull College of Art where he had sung with Addis & The Flip-Tops and Rudy & The Takeaways. Taken with Nick Lowe’s debut ‘So It Goes’ and the raw sound of other Stiff artists, Eric had scrambled a tape of his songs together and headed for Alexander Street in search of his own bit of glory Short, with an impish grin and scruffy blond hair, Eric had stopped off at a pub en route to calm his nerves. When he arrived, he stumbled drunkenly into the Stiff office.

Eric recalls: “I went in with my tape I had made in the morning and Nick Lowe was in there and I gave my tape to Huey Lewis. I just wanted to go and they said, ‘Can’t you give us your phone number or something?’ and I was terrified and gave them my phone number. I left and I thought, ‘What have I done, how stupid I am.’ Three days later Jake Riviera rang me up personally and said, ‘It’s about this tape you brought in,’ and I started saying, ‘Oh, it’s all right, you could just record something else over it. It’s just an old cassette, you don’t have to send it back, I’m really sorry.’ But he said, ‘No, we were wondering if you would like to come and talk to us and maybe talk about making a record. What are you doing, are you busy?’”

Such episodes were not uncommon. Having reeled in off the street with little more than a home-made tape and a lot of Dutch courage, the 22-year-old art student from Newhaven in Sussex had got himself a record deal and an appropriate new name – ‘Wreckless Eric’. From there, Eric went to Pathway Studios where Nick Lowe produced and played bass on Eric’s song ‘Whole Wide World’. Disbelievingly, Eric went home to await the release of his very first record.

On a subsequent visit to 32 Alexander Street, Eric discovered that Blackhill Enterprises was located in an office above Stiff. Ian Dury had made a lasting impression on Eric when he had seen Kilburn & The High Roads on the pub circuit two years before. Now Eric was moving in illustrious circles.

Says Eric: “I remember being in Stiff’s offices saying to them that Ian was fantastic and asking what he was doing and they said, ‘He’s got a solo career, he’s writing songs – there he is now.’ And there was this bloke shambling along the street with a shopping bag and wearing a mac and a pair of kickers – I just couldn’t believe it. Shortly after that Stiff put on a big gig at Victoria Palace Theatre, with Graham Parker and the Rumour topping the bill, followed by Tyla Gang and The Damned. I had recorded ‘Whole Wide World’ and we hadn’t got a B-side and I didn’t know what we were doing. I was talking to Nick Lowe and he said, ‘There’s someone you ought to meet over there’ and it was Ian. Denise Roudette was with him looking fantastic. It was astonishing – there he was. I had seen him in the distance, I had seen him on stage and I had a copy of Handsome, which was autographed, and ‘Crippled With Nerves’ and I just said, ‘You’re fantastic, you’re the best’ and I think he thought I was taking the piss. His minder Fred Rowe was standing nearby and Ian started shouting, ‘Fred, Fred’ and I thought he would have me thrown out. But Denise said to Ian, ‘No, he means it.’ So we got talking about lyrics and then Ian told me to go round and see him in his gaff.”

It was the kind of offer that Eric could only have dreamed of six months before, but Stiff was now doing exactly what Jake and Dave had hoped. It was offering a voice to singers and musicians who, until this point, had been left to watch wistfully from the sidelines. It was also developing its own distinctive feel.

On the evening of December 1st, 1976, Eric took Ian up on his invitation. Not wishing to arrive early at Oval Mansions, he went into a pub and as he sat in the bar he remembers catching one of punk’s most famous moments take place on the TV. The Sex Pistols, who had unleashed their debut single ‘Anarchy In The UK’, were appearing live on Bill Grundy’s early evening Today show. Queen had pulled out and the headline-making punk band had been called in at the last minute to replace them. But the decision was to prove disastrous. Grundy’s line of questioning was designed to goad the band into saying something controversial and when he heard Johnny Rotten muttering the word “shit” under his breath, he saw his chance. Demanding that the snarling singer repeat his “rude word” he provoked a torrent of abuse from Rotten and Steve Jones. The incident led to Grundy being suspended by Thames and Sex Pistols’ gigs cancelled around the country. It was compulsive television for the few minutes it had lasted. Eric finished his drink and walked round to Oval Mansions where he found Ian and Chaz writing together. They were putting the finishing touches to a new song as he walked nervously into the room. “What song is that?” asked Eric. “‘Sweet Gene Vincent’,” came the reply.

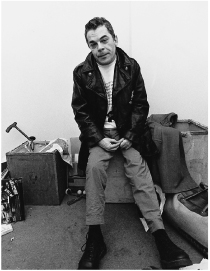

Ian circa 1978 (Rex Features)

Ian with Kilburn & The High Roads at Wingrave in early 1972. Left to right: Paul Tonkin, Chris Lucas, Humphrey Butler-Bowden, Keith Lucas, Ian, Russell Hardy and Charlie Hart. (Mick Hill)

Ian with the Kilburns in January 1973, left to right: Davey Payne, David Newton-Rohoman, Keith Lucas, Ian, Russell Hardy and Charlie Hart. (Mick Hill)

A promotional postcard for Kilburn & The High Roads featuring London landmarks mentioned in the song ‘Billy Bentley’. In the bus queue: Charlie Sinclair, Ian, Keith Lucas, Russell Hardy and Davey Payne. (Mick Hill)

Ian, probably at Wingrave, circa 1971. (Courtesy Denise Roudette)

Denise Roudette, Ian’s girlfriend during the Seventies. (Courtesy Denise Roudette)

Ian models a stage jacket during the early days of the Kilburns. (Courtesy Denise Roudette)

Ian at Oval Mansions. (Barry Plummer)

Ian and Denise Roudette, circa 1974. Note the razor-blade earring worn long before the emergence of Johnny Rotten. (Courtesy Denise Roudette)

Kilburn & The High Roads in 1975. Left to right: Ian, Rod Melvin, David Newton-Rohoman, Charlie Sinclair, Keith Lucas and Davey Payne. (Courtesy Denise Roudette)

One of the last performances of Kilburn & The High Roads in 1975. Left to right: Keith Lucas, Ian, an unknown singer, Denise Roudette, Malcolm Mortimore, Charlie Sinclair. (Gordon & Andra Nelki)

Sweet Gene Vincent.

Ian pictured backstage during the 1977 Live Stiffs tour. (LFI)

The Live Stiffs tour, 1977, left to right: Wreckless Eric, Nick Lowe, Elvis Costello, Larry Wallis and Ian. (Stiff Records)

Ian in 1978 with his Union Jack teeth. (David Como/S.I.N.)

By the time he got home that night, Eric was in seventh heaven: “I wanted to play my songs, but I didn’t know anybody and he listened to stuff I’d done. They were awfully nice and they gave me a lift home to Wandsworth in their Commer van. Even if I had gone on to work in a toothpaste factory, I would have had my moment.”

By the spring of 1977, Eric was still in limbo. He had recorded ‘Whole Wide World’ with Nick Lowe, but no B-side had been prepared and he was without a band. Since moving to London, his CV had grown to include quality control inspector at a Corona lemonade factory in Wandsworth, cleaning toilets at a tarmac company in Greenwich and clearing plates off tables at Swan & Edgars’ department store in Piccadilly Circus, where he had been hired on the basis that he could “fill in the application form”. Waiting patiently for his big break, Eric spent his mornings cutting hedges and mowing lawns in nearby gardens, but in the afternoons, he practised his quirky songs in his rented lodgings in Wandsworth, in south London. Denise had started calling around to Eric with her bass guitar and the two giggled nervously like school kids as he taught her to play ‘Hang On Sloopy’ (The McCoys’ 1965 hit). Gradually, they started to try some of Eric’s own songs and, as the sessions progressed, Denise started camping out in the living room. Only a few months before, Eric had been a stranger in London, with few contacts in the music industry, but meeting Ian and Denise had opened the door to a welcoming and creative circle of artists where he could develop his songs. Ian was also to play a very direct role in the developments taking place at Eric’s – as his drummer.

“When Denise moved back in with Ian, he wanted to come round and hear what we were doing,” says Eric. “I don’t know if he thought me and Denise were conducting some sort of torrid affair or something. He started coming round and he sort of tapped along with us and said, ‘I need to come round again with some drums,’ and suddenly we got a fire damaged Olympic drum kit that had been removed from the back of a second-hand shop by Fred Rowe. I would be clipping hedges in the morning and they would come around in the afternoon and we would just play We were this little bohemian combo and life was very charming.”

Over at Stiff, Eric’s recording of ‘Whole Wide World’ had gone down a storm and Dave Robinson wanted to know what else the scruffy singer had to offer. Without hesitating, Eric replied ‘Semaphore Signals’ and Dave suggested that as Ian was already playing with Eric that he should produce it as a B-side for his single. The song was recorded with Eric playing electric guitar, Denise on bass and Ian on drums.

Eric: “Ian wanted to be a drummer, he was very percussive. I remember some interview Ian did and he said he wanted to be a drummer, which is stupid when half your body don’t work. The thing is, it was only his right hand and his right foot that were really doing the work and he had the high hat clamped shut. He used to play the bass drum and the high hat and that was the basis of keeping it together. Then with the snare drum he would almost have the stick, not exactly taped to his hand, but giving that impression, and he would lift his hand up and drop it onto the snare drum. I mean, there wasn’t much going on there and nothing going on with his left foot, of course. It was all with the high hat and the bass drum and then round the cymbals a little bit.”

‘Whole Wide World’ featured on A Bunch Of Stiffs, a cash-in album of tracks by Stiff artists and mates of Dave and Jake, issued in March 1977. Elvis’s ‘Less Than Zero’ and Motorhead’s ‘White Line Fever’ were the only singles, while Nick Lowe weighed in with ‘I Love My Label’, a tribute to Stiff which he wrote with Jake (“Well, I’m so proud of them up here/We’re one big happy family/I guess you could say I’m the poor relation of the parent company”). Other featured artists were Dave Edmunds (who also appeared under the pseudonym Jill Read), Stones Masonry, Magic Michael, Tyla Gang and Graham Parker & The Takeaways – a studio band comprising Nick Lowe, Dave Edmunds, Sean Tyla and Larry Wallis.

On August 25, 1977, ‘Whole Wide World’ was released as a single (Buy 16), hot on the heels of Elvis Costello’s second 45 ‘Red Shoes’. On Side A, the matrix read: “Stiff Records – Wreckless Eric: We’re not the same, he’s not the same’ and on the flip-side, the label’s cutter George ‘Porky’ Peckham scratched ‘Semaphorly yours’.

By this time, Eric’s informal backing group had a new recruit. Humphrey Ocean had called around with Davey Payne and Davey asked if he could start bringing his saxophone along. His musical credentials were never in doubt and the former Kilburn immediately added a new dimension to Eric’s unusual sound. The quartet rehearsed at Eric’s over the summer months and a set gradually emerged including such songs as ‘Reconnez Cherie’, ‘Personal Hygiene’, ‘Excuse Me’, ‘Rags And Tatters’ and ‘Telephoning Home’.

Meanwhile, attempts to find a home for Ian’s by now completed album New Boots And Panties had initially been frustrated and the project looked doomed. Armed with the 10 breathtaking tracks recorded at The Workhouse, Andrew King and Pete Jenner tramped around the offices of all the major record labels, only to be shown the door on every occasion. Ian’s unnerving physical appearance and the explicit nature of his lyrics made him a virtual outcast in the eyes of record company big shots.

“They all said, ‘Oh, we really love his stuff, but it’s not quite what we’re looking for,’” says Andrew. “‘It doesn’t really have any commercial potential and it’s a shame he’s not better looking’. I used to have a file with all the notes of all the people who passed on Ian who are now the biggest moguls of the lot, all of whom would happily deny that they passed on Ian, but they did.”

But the solution was right under their feet. Downstairs they went to Dave and Jake and played them the songs which had been spurned by the major labels. Astonished by what they heard, they agreed to sign him straight away.

Andrew, who now works at Mute Records, explains: “We licensed the album to Stiff which was a very good thing, because we owned the tapes and there was never any trouble about ownership of the masters later on. If Stiff went under, all the rights automatically reverted to us. Down the line, Ian didn’t get into half as much grief as some of the other bands on Stiff.”

Of Stiff’s strategy, Andrew observes: “Stiff wasn’t the first independent label, but it was the first independent which had the bottle to take on the majors at their own game. It was something which Daniel Miller did at Mute Records a few years later, although fortunately he had his head screwed on rather better than Jake and Dave because he is still here. The other independents were quite willing to put out groovy records, but they weren’t really going to break acts and be a major player. Stiff never had any shyness about what their position in the industry should be. As far as they were concerned, they were just as much a major player as CBS, Polygram, EMI or Island.”

Commenting on the label’s unorthodox policy and on the record industry in the late seventies, Ian said,11 “Stiff was aimed at people whose arses were hanging out in the industry and couldn’t get a look in. We were the unemployables really. We didn’t fit into any of their stupid categories, since the record industry is run by shoe salesmen and drug dealers. We took New Boots And Panties to every single label, but they were just fucking stupid – they still are.”