CHAPTER 3

ALONE IN THE SWAMP

Cassie’s heart thumped against her ribs. She clenched the button tightly in her fist. How long had the button been here? A week? A day? An hour? Maybe the soldier who had dropped the button—Cassie had already begun to think of him as a soldier—was somewhere nearby even now, watching her.

Something rustled in the shrubs behind her. Seized by panic, Cassie dived for the passageway and scrambled outside, just in time to see a startled chipmunk dart away from the thicket. Hector sprang after the creature, barking, but the chipmunk disappeared into a hole.

“Mercy,” Cassie said. She sank to the ground and tried to still her racing pulse. She’d been scared for nothing—this time. But she wasn’t about to wait around for someone who was a real threat to show up.

“Let’s get on home,” she said to Hector. She dropped the button into her pocket and added, “Real quick.” She had already decided to take the fastest route back to the farm, which meant a shortcut through the huckleberry swamp. The swamp crawled with water moccasins and rattlers, but poisonous snakes seemed less frightening than the faceless image of the rogue soldier that loomed in her mind. Besides, Hector would give her fair warning before she stepped on a snake. Cassie picked out a big stick to carry, though, just in case.

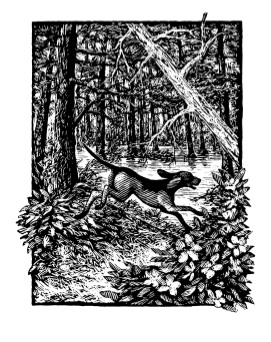

At the bottom of the hill, she turned east instead of south, and it was less than a mile to the swamp. The swamp, dotted with creamy white huckleberry blooms, looked almost inviting. Hector must have thought so; he plunged right in. Cassie started after him, following a deer trail through the tangle of huckleberry shrubs, past tall canes of swamp rose and snakeroot rising on long purple spikes. A ways into the swamp, her stomach began hurting—whether from hunger or fear, she didn’t know—and the farther she hurried through the muck and briers, the harder it was to ignore the pain.

Cassie spotted a copse of sassafras trees just off the trail, on a little hummock at the edge of the swamp. Sassafras was the best thing for a stomachache, Mama said, so Cassie decided to get some sassafras bark to chew on. “This way, boy,” she said to Hector, and started up the hummock.

When she got to the top, she saw that on most of the trees, the bark was infested with some sort of bug. As she pushed farther into the copse searching for some unblighted bark, she spied what looked like a shelter rigged up next to a little pawpaw tree. Taking a few steps closer, she could see it was a shelter: a blanket, raised a few feet off the ground by sticks to form a little tent. The other side was tied to some low branches of the pawpaw tree. Pine boughs had been piled on top of the blanket to hide it. Outside the shelter was a circle of blackened ground and charred wood, the remains of a campfire. A wooden canteen hung from the limb of a tree nearby.

Then Cassie saw something that made her mouth go dry. Slung on the ground a few feet from the campfire were a military haversack and a soldier’s forage cap.

This was a soldier’s campsite.

Was it the same soldier who had trespassed in her secret thicket?

Fear twisted in Cassie’s belly. She had the urge to run, but she made herself stay. Apparently there was no one around. Hector didn’t seem the least bit alarmed. He had already rushed forward to sniff at the campfire.

Cautiously Cassie followed Hector. She bent to touch the charred wood; it was cold. There’d been no fire here for a while, anyway. Where was the soldier who had made the shelter and left his belongings? And who was he? The fellow was obviously hiding; why else would he camp smack-dab in the middle of a swamp? He was a no-good, that was for sure, probably a deserter. Maybe he was the Yankee who robbed the Waldrops, claiming to be foraging for supplies for his troops. “Foraging,” Cassie knew, was the Yankees’ way of stealing from everyday folks without calling it such.

Cassie felt a little braver now, and curious, very curious. She moved forward to get a closer look, crouched, and picked up the haversack. Strange—it was empty. Hector pushed past her and sniffed at the haversack. Then he caught sight of a rabbit in the brush at the edge of the clearing and took off after it. In an instant both Hector and the rabbit had disappeared down the side of the hummock.

Cassie was puzzling so over the haversack, she scarcely noticed Hector was gone. Usually soldiers carried personal items in their haversacks, like mess kits, sewing kits, razors, and handkerchiefs. It was odd, she thought, that this haversack was empty. What did it mean? Had the soldier been forced to abandon his campsite? He must have gone in a hurry, to leave his hat and canteen—valuable articles for a soldier.

Cassie eyed the hat. It was bedraggled and filthy, encrusted with mud, and a color that she couldn’t name. Had it once been Yankee blue or Rebel gray? There was no way to tell, not now. Likely it had been blue, she thought, for it would be like a Yankee to slink away and hole up like this in the woods.

Then the canteen, twisting slowly in the breeze, caught Cassie’s eye. For the first time she noticed there were letters painted on its side. She watched as the canteen twisted away, then back again. Now she could see the letters clearly: CSA—Confederate States of America.

Cassie’s stomach lurched. This no-good deserter was a Confederate—one of their own. He was supposed to be fighting for the South. Yet brave soldiers like Jacob were being killed, while this fellow ran away.

Cassie felt sick with the knowledge, but angry, too. “It’d serve the coward right to be hauled off to Danville and turned over to army headquarters,” she said aloud. “To be shot, like he deserves.”

Then Cassie jumped half out of her skin as she felt her arms pinned behind her. A voice, thick and gravelly, said, “Now, missy, you wouldn’t want to see a thing like that happen, would you?”

Paralyzing fear shot through Cassie’s body. Her brain froze.

“What you doing here?” The man’s voice was angry.

He pulled Cassie’s arms tighter behind her, nearly wrenching her shoulders from the sockets. White-hot pain yanked Cassie’s brain back to life.

“Quit! That hurts!” Cassie jerked her head around fast to see who had hold of her, but he was faster. He tightened his grip on her.

“Turn me loose!” Cassie said. She kicked at his shins. He buckled. She tore one arm free and wriggled like a night crawler to pull away the other arm. His grip on her arm turned to iron, and his fingernails pressed into her wrist. His other hand, Cassie saw, was on the hilt of a knife strapped to his belt.

“I wouldn’t do that again, missy,” he said. “Wouldn’t try to run neither, if I was you. I ain’t killed a young’un yet, but my pappy claimed there’s a first time for everything. Don’t do anything stupid to make this my first time.” The man released Cassie with a shove. “Now tell me what you doing here,” he said again.

Fear made Cassie’s knees weak, but she turned and forced herself to look at the man, to look him over good. He wasn’t tall, but he was built stocky, with broad shoulders and a wide chest. He looked like he had once been muscular, but now he was gaunt, with sallow skin. He was dressed in a dark homespun butternut, like half the Southern army. His britches were torn off at the knee, and sores oozed where his brogans cut into his ankles. The front of his uniform was ripped, and—Cassie’s breath caught in her throat—some of the buttons were missing off his jacket.

“You best speak when you’re spoke to,” the man was saying. “You best answer me.”

Cassie kept her silence. She didn’t owe him an answer; she didn’t owe him anything.

“Cat got your tongue, has it?” The man took a step closer. He stank of sweat and swamp water. “Tell me, girl. What you doing out here in this swamp?” He spit the words in Cassie’s face. His fists were balled. “Answer me!”

Cassie’s pulse was pounding in her throat. “It’s a shortcut home,” she said. She prayed her voice didn’t betray her fear.

“Home.” The man’s lips parted in a menacing grin. His yellow teeth gleamed. “Now where might that be?”

“None of your durn business!” she cried.

He backhanded Cassie across the face. “Mind your manners when talking to your elders, girl. Ever’ one of my eight young’uns got better manners than you.”

Tears leaked from Cassie’s eyes, but she blinked them back. She couldn’t believe this stinking polecat was somebody’s pa.

The man spit, then glowered at Cassie. “Now I got to figure what to do with you,” he said, “being as how you’ve a mind to see me shot for desertion.” He seated himself on a tree stump and propped one bony leg on the other. “Being as how you’ve discovered my little homestead here.”

“What you better do,” Cassie said, “is get yourself on out of these woods ’fore you get caught. Don’t you know there’s soldiers swarming all over this county? I seen a passel of soldiers up at Sloan’s store yesterday.”

“Them soldiers ain’t going to come near this snake-infested pit,” said the man. “It’s just me and the rattlers here, and I like it that way. Ain’t nobody bothered me yet, nobody but a busybody young’un.” He pulled his knife from its sheath and plunged it into the stump. “What kind of ma you got,” he snarled, “that she didn’t learn you not to poke your nose in other folks’ business? Good-for-nothing, ain’t she?”

At that insult to Mama, Cassie’s hackles flew up, and words were out of her mouth before she could stop them. “One thing she learned me was the difference between a good soldier and a yellow-bellied coward!”

Cassie’s chest went tight as she realized what she had said. Alarmed, Cassie swept her gaze to the knife, expecting to see the deserter’s fingers closed around it. But he surprised her. He took his hand off the knife. The corners of his mouth turned up. Cassie might have called it a smile, if it hadn’t chilled her to the bone.

“Got me pegged a coward, do you?” he said. “Well, now, I wonder what you’d do, little lady, when the shells started flying and the bullets started zinging past your sweet little ears. And men was screaming in pain and dying all around you. What would you do?” His fingers went back to the knife and tapped against it.

Cassie’s heart pounded. She couldn’t have spoken if she wanted to.

After what seemed forever, the deserter dropped his hand. “Reckon,” he said, “you might just turn and run, like I done. You might. If you was smart.” The deserter laughed in a queer, crazy-sounding way. “Are you smart, gal?”

But he didn’t wait for an answer. His eyes narrowed, and his voice turned grim. “It don’t bother me none to kill, if I have to.” He paused. “But not for generals no more. Understand that? Reb or Yank—it don’t matter to me.”

Fear flashed through Cassie’s body like a fever. Where on earth was Hector?

Struggling against panic, Cassie forced herself to speak. “Listen, I reckon you can’t be blamed for deserting.” It was a bald-faced lie, but Cassie figured God wouldn’t fault her too much for lying under the circumstances. She rushed on. “My pa got drafted to fight with General Lee, and my brother got killed. I sure wish they’d deserted, so they’d be back here with us. See, I understand. You can turn me loose and I won’t breathe a word to nobody that I even seen you.”

A glint came to the deserter’s eyes. “No menfolk around your house, huh? And you got chickens and hogs, I reckon, and a cow. Wouldn’t a big old slab of bacon taste fine, after living off roots and rabbits all these weeks? Where you live, girl?”

Land’s sake, Cassie thought, what have I gone and said? The man was going to rob them of every lick of food they had, and likely cut all their throats to boot.

How could she undo the damage she had done?

“Danged if I ain’t lost,” she said. “Fact is, I live miles from here. Besides, you wouldn’t get no bacon at our house. Yankee foragers hauled off ever’ one of our hogs last year. And my brother Philip’s a dead shot with a rifle, and my dog Hector, he’s mean and he’d tear you up if you come near our place.”

“Hah,” the deserter said. “Reckon I can handle a scrawny old dog. Ain’t a-going to mess with you anyways. Not if you do like I tell you.” He stood up. “Take me to your house is all, and fork me out a few necessaries to tide me over till the army clears out of this vicinity.” Then he clenched Cassie’s arm and prodded her in the back with the knife.

Cassie struggled to break away. “Crazy coot! You think I’d—”

Suddenly the deserter screamed and jerked backward like a dragonfly snatched by a frog. Cassie saw a streak of red fur and a flash of teeth. It was Hector!

Hector sprang and jumped back, sprang again, snarling and snapping, ripping the man’s clothes and sinking fangs into flesh. The deserter was yelling. If Hector knew anything, it was how to fight. Wasn’t he the best coon dog in the county? The deserter didn’t stand a chance. Hector would tree him like a coon or run him off. Cassie knew the best thing she could do was run.

She raced into the woods, but stopped, suddenly, when she heard Hector yelp. Then there was a thud, and dead silence. No sound but the cackling of a crow in the tree above her.

“Hector!” Cassie cried out. Her voice rang through the silence. Frantic thoughts barreled through her mind. Hector hurt, maybe dead … Turn back, try to save him. Yeah, and get yourself killed. Keep on running—there’s nothing you can do.

Cassie wrenched herself away and started running again. Behind her, she heard the deserter crashing through the trees. She picked up her pace, but he was still back there, gaining on her. She could never outrun him; she had to hide. Where … where?