CHAPTER 4

HOME

Next thing Cassie knew, the ground started sloping downward, and she smelled water—the creek. Like a crack of thunder, it came to her. She could hide in the caves hollowed out in the creek bank!

Quakers had dug the caves to hide runaway slaves before the war. The Quakers had all left, gone north when war broke out, but the caves were still there, their mouths hidden under tree roots or in canebrakes. If a person didn’t know where the caves were, he would never find them. But Cassie knew where they were, every last one of them. Myron had showed them to her and Jacob and Philip a few years ago when they were fishing with him. Myron was a Methodist, but his wife’s people were Quakers, and he’d helped slaves escape before the war.

Cassie sprinted down the slope, purple with violets, and there was the creek—the clear, quiet creek—flowing through the shade of overhanging branches draped with yellow jessamine and bullace vines. Cassie scrambled down the bank and plunged into the water, up to her thighs because of all the recent rain. The icy water stung her belly as she leaned forward and began to swim.

She glided along, quiet as a water moccasin, heading for the black willow tree whose roots were thick as her waist. The roots hugged the bank, and between them was the dug-out cave, smaller than she remembered. She squeezed through the opening, into the darkness. The air smelled damp and musty. She could just barely turn around and face the mouth of the cave. She didn’t want to be snuck up on from behind. She lay still and listened to herself breathe. The cave’s mouth sliced the daylight into a circle, and shadows played on the walls inside.

After a while, the shadows disappeared, the circle got dark, and she heard thunder, then rain battering the creek bank and plunking into the water. A storm! The creek would rise more, covering her tracks. Maybe the deserter would give up hunting for her altogether.

Cassie hunkered down and got comfortable, as comfortable as a person scrunched up in a cave could be. Didn’t the rain, she thought, sound like it did on the roof at home? Her eyelids drooped. After everything she’d been through, she felt exhausted. She thought how the storm would keep Philip from getting his corn planted. And that’s the last thing she remembered before she fell asleep.

Cassie jerked awake in a pool of cold water. Inky darkness surrounded her. Her clothes were soaked, and she shivered. Pins and needles darted through her arms. She slithered along her belly through the standing water, toward the mouth of the cave.

A scummy gray sky hung over the blackish forms of the creek bank and trees. Dawn would break soon. It was still raining, but only a drizzle. Below her the creek roared, loud as the beating wings of a flock of geese off a lake.

Cassie dangled her arms from the lip of the cave, and her fingers touched rushing water. She pulled herself farther out of the cave and plunged her whole arm in to test the water’s speed. It was fast, very fast. Cassie could swim, but she wasn’t sure she was a match for that current. If she dawdled much longer, though, the cave might flood.

Cassie hung on to the willow tree’s roots while she eased her legs into the water. The current sucked at her as if she were a licorice drop in the mouth of a giant. Dread thickened inside her. How could she ever make it across? Yet she knew she had to try. If she stayed here, she risked being drowned.

Cassie tore her fingers off the willow roots. Her feet pushed against solid creek bottom. The water covered her chest, almost to her shoulders, and its chill numbed her. She slogged into the torrent. She struggled to keep her balance, taking slow, measured steps. The water pushed and tugged, and several times she lost her footing and nearly panicked. But she locked her eyes on the opposite bank and pushed herself on.

Finally she was close enough to the other side to grab hold of a willow limb that jutted out over the water. She hoisted herself up the steep bank. At the top, she stood for a moment, catching her breath, cold raindrops falling on her face. She thought of the button and felt for it in her pocket. It was gone. She’d lost it in the creek, or maybe in the cave or in the deserter’s camp. What difference did it make? The button was the least of her concerns now.

By this time Mama was liable to be worried half to death over Cassie. And what about Hector? Should Cassie go back after him? Her stomach knotted at the thought of going back into that swamp. Besides, she didn’t think there was much use. She had an awful feeling that Hector was dead.

And the deserter, where was he? How far had he followed her? Maybe he gave up when her trail disappeared into the creek. Or maybe he walked along through the creek looking for her. Maybe he was looking for her still …

The idea made Cassie shudder. Then she grew cold all over as an even worse possibility occurred to her: maybe the deserter had given up on Cassie … and gone looking for her farm.

A sense of urgency hammered at Cassie. She had to get home and warn Mama. She prayed it wasn’t already too late.

Cassie set off at a trot into the woods, her every sense honed to detect any hint of motion that could mean the deserter was nearby. Darkness hung thick in the trees, but the wrens were warbling; daylight wasn’t far away. By the time Cassie neared home, the sun was rising over Oak Ridge. It was pink at first, just a tinge on the horizon, and lavender clouds were laid out above like long rows of woolen socks. As the pink deepened, bobwhites began to call out from the woods that edged the field.

Cassie crossed the road, cut through the skirt of pines to the pecan grove, and came up the back way, through the cow pasture, behind the barn and privy. Her nostrils filled with the privy’s pungent odor—warm and musky and not unpleasant. A few of Mama’s chickens were already scratching for worms in the rich soil behind the privy.

Next to the privy was the barn, and Cassie could look straight through the barn’s open doorway and see Philip inside getting ready to milk June, their cow. Just like normal, Cassie thought with relief. The deserter had not found the farm. Not yet anyway.

Philip’s back was turned. He was tying June to the milking ring on the wall and muttering—muttering about Cassie. Cassie hugged the corner of the barn and listened. She couldn’t help herself.

“I swear,” Philip was saying, “Cassie worries Mama more than all the rest of us put together.” He jerked hard at the knot he had just tied, then took the milking pail from its hook and set it beneath June’s udder.

Cassie’s conscience stabbed at her. Was it true? Did she worry Mama that much?

But Philip was going on, stroking June’s neck, calming her before he sat down to milk. “Always hell-bent on her own way, that girl is, never giving a thought to the consequences of what she does. She’s just like Jacob. Just like him.”

Anger instantly replaced Cassie’s guilt. How dare Philip talk that way about Jacob! She stormed into the barn. “Durn right I’m like Jacob,” she said, “and proud of it.”

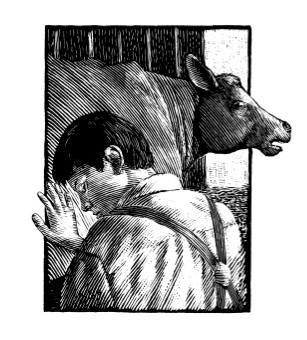

Philip was startled. He jumped. June was startled, too; her ears twitched and she stamped her feet. Philip swung his head around and studied Cassie up and down, then turned back to June and seated himself on the stool at June’s side, as if Cassie weren’t even there. He laid a shoulder into June’s hindquarter and squeezed a teat with each hand, sending two streams of milk zinging into the pail. “Where you been all night?” he finally said.

Bitterness filled Cassie’s throat. “Is that all you got to say? Is that all?” She had had a fool notion that Philip might have been worried about her.

Philip’s hands dropped. He turned around on the stool and faced her. His eyes had dark circles under them. “What should I say, Cassie? You run off and stay away all night. You get Mama worked up to a frenzy fretting over you. You give nary a thought to the rest of us; you never have. Like Jacob. You’re like him in that.” A pause. “You two and your devil-may-care attitude. It like to drove Pa to distraction.”

Hurt shot through Cassie, but it quickly changed to anger. “You got no business bringing Pa into this,” Cassie said. “You’re just jealous of me and Jacob. You always was—’cause Jacob picked me to share his secret thicket with instead of you.”

“I don’t care beans for your stupid old thicket,” Philip snapped. “’Tain’t nothing but a tangle o’ weeds, and it’s pure foolishness to make such a fuss over it.”

The thicket? Foolishness? Cassie was deeply stung, but she refused to let Philip know. “You sure pined away long and hard,” she shot back, “when Jacob wouldn’t let you see that tangle o’ weeds.”

Philip looked injured, and Cassie felt guilty—but only a little. Then, to hurt Philip like he had hurt her, she added, “You’re jealous—admit it, Philip—’cause me and Jacob got along so good and the two of you never did.”

After a long silence, Philip said, “Jealous? Maybe.” For a moment Philip rested his forehead on June’s flank, then lifted his head and went back to milking. “Jacob was my big brother, too. I worshiped him, same as you did. Like you still do. Me, I can see his faults now. Don’t you recollect all the taunting we took ’cause Jacob couldn’t make up his mind whether or not to soldier? Jacob was the only boy in the county who didn’t hightail it out to volunteer, and everybody was calling him a coward—”

“Jacob wasn’t no coward!” Cassie broke in. “You got no business saying so.”

“I wish you’d quit putting words in my mouth, girl. I never said he was a coward, only that the really important things, he never could take a stand on one way or another.”

Philip’s criticism cut Cassie like shards of glass. “That ain’t true. Jacob did take a stand. He joined the army and fought as good as anybody else—better. You heard that letter, how brave he was and all.”

“Yeah, so brave he got himself killed. A lot of good it did him.” Philip started at the second set of teats, squeezing, pulling, squeezing, pulling. Cassie felt as if her heart were being squeezed with each movement of Philip’s hands.

Then Philip made it worse. “Jacob only took a stand finally,” he said, “’cause Emma dared him to.”

Angry tears sprang to Cassie’s eyes. “You shut your mouth, Philip. How can you talk like that about Jacob?”

“It’s the plain truth, Cassie,” Philip said. The streams of milk rang against the side of the pail. “You was too close to Jacob to see how he was.”

Cassie was standing with her shoulders squared, her chest heaving up and down. Philip, finished with his milking, rose and set the full pail to the side where June couldn’t knock it over. He started untying June from the milking ring.

“I ain’t going to talk to you no more,” Cassie said.

“Suit yourself,” said Philip. He hooked his fingers around June’s halter and pulled her toward the barn door, nearly running Cassie over.

“Watch where you’re going,” she said.

Philip didn’t turn around. “You best head on up to the house. You got Mama worried sick.”

“I had a good reason why I was gone all night.” This Cassie said to Philip’s back and the backside of the cow.

“You always do.” Philip walked on, leading June out to pasture.

At that moment, Cassie hated Philip. If big-britches Philip knew what Cassie had been through …

“Cassie!” It was Emma, up the hill in the door of the chicken house with a basket over her arm. Fetching the eggs, Cassie thought. Emma, her mouth hanging open, was staring at Cassie. “Mama, it’s Cassie!” Emma yelled. “Cassie’s home!”

The shutters on the kitchen window flew open. Mama’s red hands appeared, then her face, beaming. “Don’t you move, child!” Mama hollered.

The door slammed, and Mama came running toward Cassie—Mama and Emma both. Cassie ran toward them. She fell into Mama’s arms.

“My baby, my baby,” Mama kept saying. She was kissing Cassie’s head, and her sweet, rough hands were against Cassie’s cheeks. It was the old Mama again, the before-the-war Mama.

Cassie wrapped her arms around Mama’s neck and pressed her face to the warmth of Mama’s skin. She felt tears welling up inside her and spilling over, and she didn’t try to stop them. This was the closest thing to happiness Cassie had felt in a long time.

Then Cassie happened to lift her head and look back toward the barn. There was Philip, standing under the overhang of the barn’s roof, watching them. His shoulders were thrown back, and his mouth was a tight line.

His eyes met Cassie’s. He stared hard at her. But he didn’t move toward her. And he wasn’t going to, Cassie knew.

The first thing Mama did was whisk Cassie into the kitchen to sit in front of the fire. Next she sent Emma to the house to fetch her rose-and-vine-pattern quilt. “It’s the warmest thing we got,” Mama said as she set to work fixing Cassie a cup of hot catnip tea. Myron and Ben were at the table, finishing up bowls of grits.

When Emma came back with the quilt, Mama wrapped Cassie in it, stripped off Cassie’s wet clothes down to her chemise, and rubbed Cassie’s hair dry with the big linen towel Mama saved for company. Last, Mama stuck Cassie’s feet in a pan of hot water.

All this time, Mama wouldn’t let Cassie speak a word. Every time Cassie opened her mouth to try to talk, Mama clucked and said, “Not a word, child, till that tea is gone. I won’t have you coming down with croup or pneumonia or some such thing. Influenza’s going around, ain’t it, Mr. Myron?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Myron said, wiping his mouth on his sleeve. “My Mary”—that was his wife—“been all over the county nursing folks what’s down with it.”

Cassie tried to bolt down her tea, but it scalded her throat. The best she could do was take hurried sips and listen to Myron. He was telling her how he and Philip had been out half the night hunting for her.

Myron glanced at Philip, who had just come in and was pouring himself a cup of coffee—not real coffee, but the kind everyone made with roasted okra seeds since the war had begun. Philip met Myron’s eye briefly, then looked down into his cup.

Myron cleared his throat and went on. “We give up around midnight when the rain got so heavy we couldn’t see two feet in front of our faces. I was going to try to scare up a search party this morning, and Philip was going to get some chores done till I come back. But your ma wanted both of us fed and full of hot coffee first. It’s a good thing, too, since it don’t appear we’re going to be needing no search party.” Myron smiled in Cassie’s direction.

“But, Mr. Sweeney,” Cassie said, gulping down her last mouthful of tea, “you do need a search party. Only not for me—for the deserter hiding out in the huckleberry swamp.” Then Cassie told her family all about the deserter—how he had threatened her and tried to force her to lead him back to the farm, how Hector had saved her and paid for it with his life, how she had hidden all night in the Quaker cave and nearly drowned trying to cross the flooded creek.

By the time she finished her story, Cassie was almost in tears. Mama sat down on the deacon’s bench beside her and clasped Cassie’s hand. “Mercy, child, what you been through,” she said. “But it’s over now. You’re home safe.”

Cassie couldn’t help voicing the anxious feelings that were consuming her. “What if it ain’t over, Mama? What if the deserter comes here?”

Cassie saw the worried glance Mama shot Myron, even though she quickly covered it with a smile. “That ain’t likely,” said Mama. “How would he find us? And what do we have that he would want?”

“Food,” said Cassie. “All our food. And June. Maybe even Birdie.” Birdie was their mule.

Then Ben, who had been gulping down his third bowl of grits, suddenly piped up. “Betcha it was him done stole your ash cake, Mama. I told you it wasn’t me. Betcha it was him.”

Ben’s statement hit Cassie like a blow. Could it have been the deserter who stole the ash cake? Cassie remembered Ben’s tearful protests of his innocence. They had all just assumed he was guilty; his fondness for ash cakes was no secret, and there was no one else to blame. A shiver tingled down Cassie’s spine. But now there was …

A tense silence filled the room. Finally Emma broke it. She had a horrified look on her face. “Mama, you don’t think it was Cassie’s deserter who took the ash cake, do you?”

To Cassie’s relief, Mama didn’t hesitate a minute. “No, I don’t. Why would a scalawag like that stop at taking one ash cake off a windowsill?” She paused and patted Cassie’s hand. “We ain’t going to fret ourselves to death over him coming here. It’s a good piece to the huckleberry swamp through thick piney woods. He ain’t likely to find his way to our farm without being led. Still, just knowing his likes is hanging around makes me nervous. ’Specially with Hector gone. I don’t want nobody in this family traipsing off alone till that man’s caught. For no reason. You hear me?”

Cassie and the rest agreed.

Then Mama hugged Cassie. “We come too close to losing something mighty dear to us last night. And we been—I been, anyway—dwelling too much on what’s been lost. I’m thanking the good Lord now for preserving to us what he has.”

Myron drank the last of his coffee and stood up. “Tell you one thing,” he said. “It’s plain this deserter feller meant Cassie a lot more harm than he had a chance to do. And I ain’t sure we seen the last of him. I’ll see what I can do today about getting up a search party to catch the rascal.”

Then Myron’s voice took on a tone that made Cassie feel cold all over. “Till then, you young’uns stay clear of them piney woods, hear?”