Wellness.

Until a few years ago, if you had mentioned wellness to me, I would have assumed it was something they asked you about right before handing over some crystals, scented oils, a CD of ambient music and a complimentary psychic reading.

Well, if you excuse the attempt at humour, there’s no making light of the whole ‘wellness’ gauge by me these days. Australian Cricket has taken huge strides with its approach to injury prevention with all the players around the country. Gone are the days when blokes would be the best judge of their own fitness, or a state physio would take care of pretty much everything from diagnosis to recovery.

These days, data is collected, crunched and then acted upon. Your pre- and post-game or training regimes include at least one spot of data entry into the AMS (Athlete Management System), and you know that these regular inputs are examined and interpreted as to your wellbeing. It won’t help you bowl an outswinger or fix a batting flaw, but the aim is to ensure that you are at your best physically and mentally, more often than not.

It’s not an exact science, and when tied to selection availability (commonly known as the ‘rotation policy’), can cause plenty of angst with players and fans alike. The first time I was ‘rotated’, in the West Indies in 2012, I was ropeable at first. But over the years, I have seen it from the other side too, and it has helped me and my captains with how they use me in matches.

I’ve been blessed to have played under some superb captains. At the Redbacks, my skippers included Boof, Nathan Adcock and Graham Manou, who was a mate before he was my captain.

In Queensland, I had Chris Simpson as my first captain and he was a thoughtful, innovative bloke who had a great feel for people. Since then, James Hopes has been the man with the Bulls and the Brisbane Heat, and he and I are definitely on the same wavelength. He bowled with ‘hot spots’ (effectively old or new stress fractures) in his back for much of the 2013–14 season and I know that he would never ask me to do something he would not ask himself to do first.

Ricky Ponting and Michael Clarke have very different captaincy styles, but both knew when to push and when to ease off and, importantly, when to protect bowlers from themselves. Michael was adept at taking input from so many different quarters—the coaches the support staff the players—and making the right call. It may not always have been popular, but inevitably it was the right call.

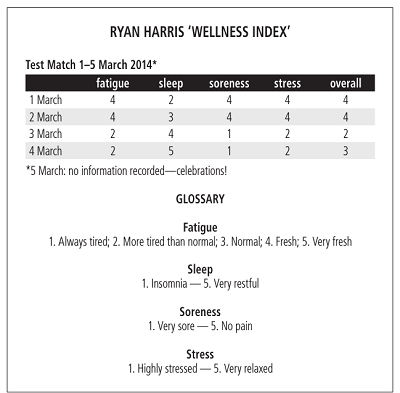

Here are a few numbers to help you get into this, from the numbers I put into our online player reporting system during the third Test match in South Africa.

As you can see, I went from being fairly fresh to being in less-than-ideal shape. And as is the case with human nature, you tend to mark yourself lower the worse you are feeling.

Here are a few other numbers that are relevant. For the second and third Tests, several of us wore a GPS harness that tracked the distance we covered, whether bowling, in the field, or batting.

In the second Test I racked up 43 kilometres and the third Test I got 42 kilometres under my belt. That’s a lot of short, sharp sprints and impacts, although nothing you don’t prepare for through off-seasons, preseasons and regular conditioning.

Cumulatively, though, it was wearing me down.

By the time the third and final Test came around in Cape Town, my body was like one of those WWII bombers being nursed home from a raid, with bits and pieces falling off them from all of the flak damage as they limped back to base, finally flopping onto the tarmac with just fumes left in the tanks.

That Test was one where the Australian spirit was thoroughly challenged, and the efforts of our motivated and dedicated touring medical staff in overcoming the waves of walking wounded was nothing short of stupendous.

You couldn’t go past the courage of Michael Clarke, whose battered and bashed limbs were aching from the working over he received at the hands of Morné Morkel and Dale Steyn during the first innings. He wore short balls all over—thumb, forearm, elbow, shoulder and head, with the blows to his shoulder enough to fracture it.

Getting hit by a cricket ball at speed is a unique and terrible sensation. As a bowler, I tend to inflict more than I get, but we all get hit. It doesn’t really matter whether it is at training or in matches, the sensation remains the same.

It gets there fast and the impact is immediate. If it hits unprotected flesh or bone, you get a crushing sting, followed by a numbness that spirals outwards from the crash site.

That’s only temporary though. The aching and deep throbbing usually follows hard on from that, as the outraged nerves in the area begin to spew out their frantic signals to your stunned brain.

If it has hit somewhere near the head, you are likely to be in a fog with your ears ringing.

If it has cut or grazed you, there can be an eerie delay as your addled senses work out whether the wetness is sweat or blood. If you can see it splattering on your clothes or the pitch, a degree of shock is normally not far away.

Even if it hits a piece of protective apparel, the outcome will be much the same.

Getting hit in the same place more than once heaps indignity upon the inevitable injury. The chink in your armour is being exploited by the opposition. As a bowler, you know you can get on top now.

Anyone who saw how relentlessly Mitch Johnson pursued the English and South African batsmen in 2013–14 can recognise that no matter how much courage a player can muster, or tells themselves they have to produce, self-preservation at a subliminal level will change how you play.

Picking up the pieces afterwards is the challenge that everyone faces. The best result is bruising. At least you know they fade.

Newcomers to cricket dressing-rooms are forgiven if they find their eyes drawn to the muddy patterns of healing bruises across the legs and midriffs of players as dressing or undressing takes place. ‘Don’t they hurt?’ is the obvious question.

Yep, but not as much as when you get them.

Someone like Michael Clarke was as well equipped as anyone to deal with it. Targeting of captains by opposition teams is a trend, heck even a tactic these days. We’d successfully squeezed Alistair Cook during the Ashes and had some success keeping Graeme Smith away from big scores during this series.

Pup wore each of his blows, and when he gained the respite of the team rooms, with a century in his keeping, we all knew his defiance had given us a massive win.

The word ‘tireless’ should be somewhere on Alex Kountouris’s business card. As physiotherapist to the team, his efforts sometimes seemed otherworldly. For someone whose well-meaning advice was often overlooked by certain head-strong cricketers who must surely know better, he was remarkably sane.

Having a team doctor on this trip was a godsend. Dr Peter Brukner was unflappable, no matter what was served up to him. A sports medicine specialist whose most recent engagement before us had been two years in the high-stakes world of the English Premier League with Liverpool, he tackled the lame and the ill with equal parts humour and quiet efficiency.

Part of me still shakes my head when I think of the number of tours that Australian teams have gone on in the past without a doctor on board.

I had been solid without being dominant in the first two Tests, and hadn’t been terribly happy with my bowling. But as a group, we felt we were in top form coming into the last Test.

Towards the end of the third day, with South Africa only a few wickets away from being dismissed for 287, I had a few moments when despair hit.

Pup was asking me how I was and I didn’t pretend. ‘I don’t think I can bowl another over’, I told him.

I had been saying that to different people on and off during the series. My normal response when I am playing is that I say I am right to go whenever I am asked, whether I am or not, because by the time I get into the middle, I am so into the prospect of bowling that I end up being right. Adrenaline and anticipation tends to be good nerve blockers, and after that I am usually a fair judge of when I need a spell or whether I can keep going.

Damian Mednis, our big blond conditioner, had spent a fair bit of time with me at Queensland before joining the Aussie setup. An athlete himself originally, and with a background in Rugby Union before coming to cricket, he knew when to console and when to jolly you along.

We’d be at breakfast or waiting to get on the bus and the exchange would go along these lines.

‘How are you H?’

‘Yeah, not that good mate, I’m not sure if I can get out there this morning.’

‘F off. Don’t be soft.’

off. Don’t be soft.’

‘Nah nah, it’s no good mate.’

‘Bull. Don’t be late for warm-up.’

And then he’d wind up someone else or if his beloved Parramatta had managed to win an NRL match, he’d luxuriate in their brief success for a while as I shook it off, either with a laugh or a scowl depending on how sore I really was.

My confession to Pup gained me some respite off the field that afternoon, but deep down I knew I wasn’t going to be able to quit. We took our 207-run lead and batted to stumps, finishing at 0–27, with the anticipation of a strong day four batting effort to set up a final day to bowl them out.

That night, the campaign to buy me two more days began in earnest. It featured a lot of poking and prodding, and it hurt. A lot. There were times I thought I was about to vomit as ‘Lex’ leaned in and tried to free up the tendons and muscles that were crying out for relief. The Doc was dry-needling my hip flexors, my hip and my abdominal muscles and there were moments when I basically could not lift my leg off the bench.

The physio room was doing double duty as a bunkhouse during that Test. Pup slept on the physio table at one stage, opting to rest where he was, until roused for more treatment.

My knee was not locked, but it was seizing up, and my running had begun to change. I was overcompensating and running more stiff-legged, trying to protect the knee. I was starting my run-up a bit earlier and trying to get the momentum going, and as I was doing that, the hip flexor began to flare up.

It was half-way through a game with the final surge to come. We knew there was plenty of time in the game to bowl them out but it was important that I could get out there with the others. When you are a bowler down, it is very hard to win games. The Newlands pitch was showing no signs of breaking up, so that wasn’t going to make up for being one short.

As a bowler, there is no worse feeling than breaking down in the middle of a game when the game is there to be won. It had happened to me several times—with the Redbacks, with Australia at the MCG. The prize is there—you can see it—but the feeling of letting everyone else down overwhelms all else.

If I wanted to be there for the crowning glory of a South African series win after an Ashes triumph, for the biggest cold beer of the lot, then I … we … needed to find a way.

The morning of day four dawned. Like everyone, my wife, Cherie, knew that there was one gigantic push needed. I was trying not to be grumpy. I had got some sleep, not much, and was still very ginger. Getting on the bus I felt like I was battling to lift my leg up. I was pretty quiet.

The plan for the medical and coaching staff was simple. At whatever point the skipper was beginning to think about a declaration, give them an hour, or as much notice as possible, to get me and the other bowlers ready.

I had treatment the entire morning. Ice, dry-needling, stretching, rubbing, coupled with the now mandatory anti-inflammatories and painkillers. It was a day where our batting ebbed and flowed, but watching Dave Warner accelerate on the way to a slashing 145, his second big ton of the match after hitting 135 in the first dig, got the blood pumping in ways that the tireless hands of the medical and support staff could only dream about.

The tip on the declaration came. We got some tape where it was needed and everything moving in the right direction so I was ready to warm up when we declared at 5–305 with a lead of 512 and a maximum of 142 overs to bowl. Adrenaline was in abundance but Pup and Boof took the extra time to make sure we were all focussed and knew our roles.

We had about thirty minutes to bowl, before tea, and then a final session to take us close to what we hoped would be a winning position on the final day.

Graeme Smith had announced this was going to be his last Test and both teams made sure his final innings was acknowledged with appropriate respect and appreciation. It’s tough when you know that someone is in their last game, which obviously means a lot to them and their teammates, but is also standing in your way. We put that sentiment aside quickly, though.

I’d had a bit of success against the burly Proteas left-hander in this series but my breakthrough came a few overs in when I brought one back to trap Alviro Petersen in front to get the first of the 10 wickets we needed. Lost in all of this was the fact it was my 100th Test dismissal, and while the job remained to be done, I still had a moment to think of Mum, issue a silent sign to the heavens, before getting back to work.

Mitch followed the next over to bring down the curtain on Graeme Smith’s career and then smashed through Dean Elgar’s stumps to have them reeling at 3–15. But AB de Villiers, at the time probably the best or at least most consistent batsman in the world, wasn’t going down without a fight. He and Hashim Amla fought hard either side of tea, but when young gun Jimmy Pattinson broke through to remove Amla and have South Africa 4–68, the home side looked unlikely to hold off our looming victory in the final session.

But AB kept going. He batted … and batted … and batted. For 326 minutes and 228 deliveries to be precise. Most of us were almost delirious with relief when I got a ball to move just enough to kiss the edge and be gloved by a grateful Brad Haddin. That dismissal opened the door for us, and Faf du Plessis and JP Duminy both fell (Steve Smith and Mitch doing the job for us). But the time was starting to evaporate and South Africa were perhaps one more dogged partnership away from holding us at bay.

There was drama too. We were convinced we had Vernon Philander caught off the glove from a brute of a short ball by Mitch. Umpire Aleem Dar gave it out, but it was overruled on review, which sparked the now infamous blue between Pup and Dale Steyn. I wasn’t close enough to know how, what, or why … but it left both men steaming. It was probably the angriest I had seen Pup since his exchange with Jimmy Anderson during the Ashes and again, flagging spirits were lifted. Mentally and physically, we were almost spent. All of those matches, all of that travel, all of that training, all of that pressure, all of that expectation, all of the relief that followed. No wonder we were having to grit our teeth. Pup was trying everything—one over stints, tying down one end and attacking from another.

The former Australian and Queensland quick Michael Kasprowicz—who knew something about having to perform under duress after almost bowling himself into the dusty Indian wickets during Australia’s 2004 tour—used to talk about the ‘niggle worm’. It was the mysterious critter in a bowler’s body that would move around, settling in a shoulder one moment, the back the next, the hip, the ankle. It was usually just enough to be uncomfortable and raise unwanted thoughts as to whether it was a sign of something serious or just the regulation aches and pains that come with regular physical labour.

Well this time, it had gone a bit past that—I was wrestling with a ‘pain snake’ that was striking any and everywhere the longer the game went on. You start off with a tender hamstring in the morning, notice an ache in your knee at lunch, and by the time you lie down to sleep in the evening, all you can feel is a sore back.

While I was treading a well-worn path endured by other Aussie quicks, Kasper’s droll quip from that Indian series—that if he succumbed to the torturous conditions in the heat and humidity of the Subcontinent, at least he knew he would have died doing what he loved for his country—wasn’t one I was especially keen to emulate.

I watched some highlights of the final days of the Test a few months later during my rehab at the National Cricket Centre. The first thing I noticed was that my run-up and action were nowhere near as ragged as I imagined they had been. I had felt like our dog Hank’s favourite chew toy after a vigorous game of keep away, with nothing quite where it should be. Instead, I was getting to the crease relatively normally.

But when I saw myself walking back to the mark, the only thing I could think was that my wincing bow-legged gait reminded me of one of those weekend cyclists after they finish a lengthy ride on a Sunday morning.

Watching those final 5 overs, where we needed 2 of the final 3 wickets of Vernon Philander (who had got to 50 in pretty neat fashion), Steyn and Morné Morkel, I admit I was wondering where the breakthroughs were coming from again.

We just needed to keep in control. I could see the floodlights had been turned on, even though the light was still fine, but I guess that with there being every chance the match could be played through until the final moments, it was better to have them on if we went deep into the twilight.

Yes! Mitch strikes Philander on the pads—could this be the breakthrough? No sooner had the ‘not out’ been indicated than we had referred it for review. Again though, the third umpire disagreed with our assessment and the decision was not overturned.

Two balls later and the ball was back in my hand.

‘C’mon Harry, time to pull the trigger.’

‘One more effort Rhino. Big charge mate.’

‘We’ve got this mob—we’ll be drinking winner’s piss soon. Go get ’em mate.’

I could barely register who was patting me on the back, or who was in my ear each time as I trudged back to the mark, wincing as I turned each time. But I kept going.

Just stay with it. Keep it simple and get the ball in the right area. Build the pressure, bowl with intent, keep it full and bring one back if you can.

Here we go. Steyn on strike, touch my chest, ignore the pain. Run in and let it rip.

And then the sound engulfed me. The ball had done what I had been striving to accomplish with it. It was full, pretty much a yorker, and it moved enough for the batsman to get an inside edge onto the stumps. Gone. We are back!

No pain now. Back to the mark. The slaps on my shoulders, back and bottom were vigorous. Morkel on strike and 5 balls in my over to go. Boof is up and down and seemingly everywhere on the boundary. Information is being pushed out and interpreted. It’s going in, and being processed, but part of me is still gnawing away at how I can get this last wicket. The ball has been reversing and I think I can get them either leg before or bowled if I can put it where I want it. Here we go …

NO! I tried too hard and pushed it down leg, so the tall tailender was able to handle it without too much trouble. Morné is normally a fairly affable sort of bloke, with an easy smile, but a quick glance at him showed a strained and nervous face behind the grill.

And again. Ready at the mark, and in.

And this time, I can’t hear the sound. It was fast, quicker than the previous ball, and it tailed back. It was full, and it reversed enough. He couldn’t get the bat down quickly enough and the only thing it could hit was the stumps.

I think we charged around for a bit then. I honestly don’t remember, other than the immense feeling of relief that washed over me after the initial wave of jubilation. A job well done.

I was nabbed by a journalist and asked what was going through my mind. I didn’t think I could come up with anything profound, but I did offer that what we had just played was ‘Proper Test-match cricket’ and that it was bloody hard.

After being secretly disappointed that I hadn’t bowled like I wanted to in the first two Tests, it was fitting that my best effort had come in the last Test, when my body was pretty much at its worst. The one thing that the ‘wellness index’ can’t capture is the will within a person. You can have the worst night’s sleep, be stressed, sore and out of sorts, but if your spirit and competitive instincts can drive you past that, then no amount of science can accurately determine if you should be playing. The good thing is that the team management and our sports scientists are on the same page—using the data we capture as a guide to ensure the players are best placed to perform more consistently for longer.

The light was beginning to be replaced by the artificial glow of the floodlights and I managed to check out the board. We had triumphed with just 27 balls left in the match.

What a finish to a game, a tour, a season, a summer … it will take something very special to top that in the years to come for anyone who was involved.

What a finish.