The Pinewood Years

LONG BEFORE HOLLYWOOD BECKONED ME, I FOUND MYSELF auditioning for a film at London’s Pinewood Studios. Little did I realize that it would be my home three decades later for a major TV series and seven Bond films. But before I get to that, I thought it might be an idea to start where I started – and that was at the very epicentre of the British film industry: Wardour Street in London’s Soho district, though admittedly my first cartoon filler-in job was on D’Arblay Street just around the corner.

It was such an exciting experience for a cinema buff like me to walk along seeing all the familiar logos of the major film companies, including ABPC (at Film House, 142 Wardour Street), Rank (at 127), British Lion, Paramount, Hammer (at Hammer House 113-117), Columbia, Warner-Pathé and others that were all congregated on this one magical road. Wardour Street was named after Sir Archibald Wardour, the architect of many of its buildings, though along with all the famous film interests it also had its share of, shall we say, more ‘dubious’ operators in the area and this caused the street to be known – even on the sunniest of days – as ‘shady on both sides’.

It was to here that hopeful producers ventured with scripts firmly tucked under their arms, would-be directors wooed film chiefs over lunch, and some aspiring actors even attended auditions.

Many of the aforementioned companies also, at one point or another, controlled the film studios where yours truly hankered to work – Rank owned Pinewood and Denham, ABPC owned Elstree, British Lion controlled Shepperton, and Hammer were out at Bray. While there were smaller concerns at Beaconsfield, Ealing and Southall, it was the larger studios that offered the most tantalizing prizes – Pinewood being the largest of all.

In 1947 the view across the fields on the approach road to Pinewood was broken only by a cluster of tall pine trees, and then, as if from nowhere, appeared the mock-Tudor double-lodge entrance, and a friendly commissionaire. It was just like arriving at a stately home.

At that time I was a rather green twenty-year-old lieutenant serving in the Combined Services Entertainment Unit and being tested for the male lead in The Blue Lagoon. It marked the beginning of my long association with the studio and now aged eighty-six I am Pinewood’s oldest (and longest-serving) resident, as I moved in to my office there during 1970, when I began work on the TV series The Persuaders! and I’ve been paying rent ever since.

An early publicity shot from MGM.

British film mogul J. Arthur Rank opened his Pinewood Studios in 1936 as his dream rival to Hollywood; the final syllable of which, plus the abundance of pine trees on the 100-acre site, gave him the name. When I first turned up, the studio hadn’t long reopened after being used during the war as a base for the army, RAF and Crown Film Units making documentaries. One stage was also requisitioned by the Royal Mint – some say that was the first time that Pinewood had made any money.

Just before my arrival, great film-makers were hard at work – names such as David Lean, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, Ronald Neame, Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat – making some of the country’s greatest films, including Great Expectations, The Red Shoes, Oliver Twist and Black Narcissus. Even as a young studio, Pinewood had an outstanding reputation.

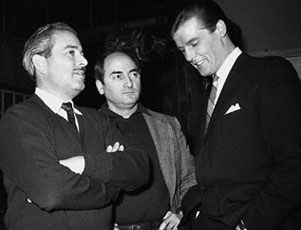

With Bob Baker and Monty Berman, producers on The Saint. Flat feet, boys? A likely story!

During the war years, my two future Saint producers, Monty Berman and Bob Baker, were both sergeants in the Army Film Unit stationed at the studio. Being the young tearaways they undoubtedly were, they’d found a way in under the wire, and used it for coming back after late-night shenanigans in the hotspots of Iver Heath. However, one night, just before breakfast, actually, they were caught midway under the wire, and were hauled up in front of the adjutant.

‘What’s your story?’ he asked Monty.

‘Well, I missed the last bus, sir,’ Monty replied, ‘and had to wait for the first one this morning.’

‘Why didn’t you walk?’

‘I have flat feet, sir, so I can’t,’ Monty added.

Bob was then brought in.

‘Why were you back so late?’

‘I missed the last bus, sir.’

‘Why didn’t you walk? Have you got flat feet too?’

‘No, sir, but my friend Monty has ... and I couldn’t leave him on his own.’

They were both stopped a week’s pay.

Bob, I should add, was the first allied cameraman in the ruined Reich Chancellery after Berlin fell and was a formidable cameraman as well as a hugely talented producer and director.

For my first screen test, I was led from the grandeur of Heatherden Hall, which formed the centre of the studio lot, through long clinical corridors across to one of the five stages – a huge, dark, soundproofed room with a smell of greasepaint, make-up and burning filters on the giant lamps. Soon it was my turn to step under the lights and in front of the cameras. Even though I didn’t get the part, I was thrilled just to be there.

Later, I learned that I had been recommended as a possible ‘contract artiste’ for the studio’s Company of Youth, more often referred to as ‘the Rank Charm School’. Now unheard of in the modern industry, the studio had then established a stable of aspiring talent, producing its own stars of the future: Christopher Lee, Joan Collins, Anthony Steel, Diana Dors, Donald Sinden, Kenneth More and Petula Clark were all under contract.

Sadly, for me, it was at a time when John Davis, the much-feared company MD, was dealing with a £16 million overdraft. They consequently weren’t interested in a young Roger Moore being added to the roster and ever-increasing wage bills. So while I mixed socially with my Rank contemporaries, I had to slip off to earn a crust elsewhere, but I always dreamed of returning to the wonderful film factory in the Buckinghamshire countryside.

Meanwhile, over at Shepperton Studios, where I occasionally auditioned for bit parts, Hungarian filmmaker Alexander Korda was busy building his empire, and while prudence was the watchword at Pinewood, extravagance was the order of the day at the rival studio, where the charming movie mogul began an impressive production programme: The Third Man, The Fallen Idol, Anna Karenina, The Wooden Horse being a few of the films I marvelled at over in the Odeon Streatham. Korda – unlike his Methodist rival J. Arthur Rank, who was a reserved and very unlikely film industry magnate – was a great showman who loved and courted publicity. He was also an astute and talented filmmaker in his own right and made his opinions known.

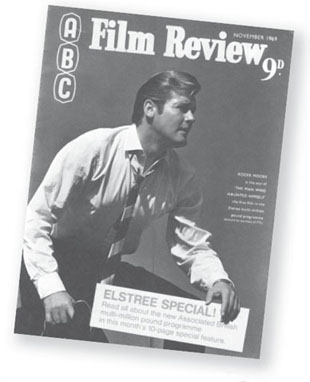

What can I say? Another early publicity pose, this time from Warner Bros.

Guy Hamilton, who directed two of my 007 outings, told me one of his favourite memories of Korda, when he worked as an assistant director to the great man. Korda summoned Guy one Saturday morning, together with one editor, one cameraman and one assistant art director, to view the rough cut of Emeric Pressburger’s first and only solo directorial effort, Twice Upon a Time. It was obvious that retakes were on the cards. The three Korda brothers (Vincent, Alex and Zoltan) walked in. The lights went out and they watched in silence until the end at which point Alex lit a cigar and addressed the assembled group.

‘Boys, I could eat a tin of film trims and shit a better picture.’

Although Korda was based in Piccadilly and rarely ever visited the studios, there was always the ‘threat’ that he might descend at any time and in the studio restaurant a large round table in the corner was constantly reserved for him.

Just before one of his rare planned visits, studio manager Lew Thorburn had stained the wood that ran the length of the long interconnecting corridors of the main house a lovely shade of red. It really was immaculate. Korda arrived and walked partway down the corridor before turning to Lew and in his thick Hungarian accent said, ‘Lew, this corridor smells of cats’ piss. Do something about it.’

One of the aforementioned great films backed by Korda, and one of my favourites, was The Fallen Idol directed by Carol Reed, on which Guy Hamilton was his First Assistant Director. The house used in the film, by the way, was the Spanish Embassy in Belgrave Square. One of the supporting cast members was Dora Bryan, who told me she received a call to audition at Shepperton to play the part of a prostitute. Very excited, she took the train out from Waterloo and on arriving at Shepperton Station, realized that the studio was actually a couple of miles away. So she walked across the fields, arriving rather the worse for wear.

Looking exhausted and a little flustered, but in her very best red dress and poshest shoes, she read the lines and Mr Reed offered her the part and told her to report to the studio at eight o’clock on the Friday morning.

‘What should I wear, Mr Reed?’ asked Dora, wondering just how tarty he envisaged the character.

He looked her up and down and said, ‘What you’re wearing today is fine.’

Poor Dora! She didn’t know whether to feel insulted or not!

Another inimitable actress at that time was Dame Thora Hird who had, by the time Dora and I took our first steps inside a studio, been making a name for herself in films at Ealing Studios – a much smaller, but equally prolific facility as Pinewood. Dame Thora later told a wonderful tale about the mealtimes there.

Prior to the lunch break each day, one of the carpenters or electricians would usually go down to the canteen to get a copy of the typed menu for the day and bring it back to the set for the crew to place their orders. On one particular day, an electrician produced the menu which offered: fried Spam and chips, cold Spam and salad, Rissoles and a couple of other items ... only the capital ‘R’ on the old typewriter wasn’t working correctly and instead printed as a ‘P’.

‘OK, then,’ said the spark to the formidable canteen manageress. ‘We’ll have three Spam and chips, four Pissoles and chips ...’

‘What did you say?’ snapped the dinner lady.

‘Four Pissholes ...’

‘That is an R! An R – did you hear me?’ she screamed.

‘Oh, sorry,’ replied our trusty spark and, without missing a beat, continued, ‘We’ll have three Spam and chips and four R-soles and chips, please!’

All of the British studios remained busy through the 1940s, but when television became a real threat the government introduced a tax on box-office receipts, which was to be reinvested in British films. Called the Eady Levy, it helped to attract many overseas producers to the British studios, including Walt Disney and my friend Albert R. ‘Cubby’ Broccoli. Once here, they stayed because, quite frankly, they fell in love with our studios and technicians. That love led to millions of pounds being injected into the UK economy and employment for many, many actors and creative personnel.

As I write, Pinewood is buzzing with activity and the big news is that Disney have moved in again, but this time on a ten-year rental deal bringing with them Star Wars, and the first film in the new series is directed by my friend J.J. Abrams.

I say ‘again’ because it’s not the first time Disney has set up at the studio, as back in 1952 they became the first ‘renters’ to move in.

Whereas back then British studios had a regular tea trolley visit the stages twice a day, part of the American way of working was to have continual refreshments on set, and Mr Disney was adamant – he wanted hot and cold running drinks all day.

Keen to avoid what he thought would be a mass daily invasion from surrounding stages, Pinewood’s Managing Director Kip Herren suggested one of the old brigade of tea ladies, Margaret, would man the station and thereby, after a few days, would recognize the Disney crew, despatching any interlopers with a flea in their ear. All was well and good until one day a tall moustached gentleman in a raincoat asked Margaret for a cup of coffee.

‘No you don’t,’ said Margaret. ‘You’re not on this production.’

‘Oh, but I am, I assure you.’

‘I don’t think so. I know everyone on this set and you’ve not been here before,’ Margaret continued, as she picked up a copy of the unit list. ‘So, come on then, what’s your name?’

‘I’m Walt Disney,’ the man replied with a big smile.

Margaret melted into a corner, but Disney was apparently delighted that his pennies were being looked after so diligently.

Disney’s newest employee, J.J. Abrams, came to my aid recently (and I’m so delighted he’s achieved great success since giving this old English actor a job as a British spymaster on the long-running ABC TV series Alias) when Lucasfilm (a division of Disney) moved into the corridor just down from my office. The next thing we knew, their part of the corridor was sealed by security doors through which access could be gained only via a swipe card. Ordinarily I wouldn’t have raised an eyebrow, as different productions have all had different security arrangements over the years, but the problem in this instance is that the kitchen and gents’ loo are all situated in the inaccessible part of the corridor – meaning no tea, and perhaps even no pee.

Pinewood staff shrugged their shoulders saying ‘that’s what the client wanted’ and didn’t offer any real alternative save for using the workmen’s lavvy in the other direction, which, to be honest, wasn’t somewhere I’d have sent a workman – let alone an international megastar such as myself – to fill a kettle. (They’ve since refurbished it, I’m pleased to say.)

I dropped a line to J.J. – who was still in LA – asking if we could use the kitchen, and promising that we wouldn’t spill any of the secrets of Star Wars. The next thing we knew, not only was access granted but an apology came from Pinewood for inconveniencing us. Ah, what it is to have friends in high places.

My book on The Secrets of Star Wars, meanwhile, will be in shops later in the year …

Television became hugely important to me in my career, and in the late 1940s my first, and a very handy, means of earning an extra few quid through the medium came when my agent Gordon Harbud suggested me for some assistant stage management work (as well as acting gigs) at Alexandra Palace.

In doing a little bit of research for this book and googling myself, a certain well-known reference website states that my first TV appearance was in 1950 for The Drawing Room Detective.

That’s not correct, dear readers!

My first tentative steps as a TV actor were taken a full year earlier in 1949 at Alexandra Palace, more fondly known as Ally Pally. The BBC produced most of its early TV programmes at Ally Pally in north London and as such it’s often referred to as being the ‘birthplace of television’. While I wasn’t old enough to be there for the birth itself, back in 1935 when the Corporation leased the building, I do vaguely remember the following year as an excited nine-year-old when it started its broadcast trials; up until then our only mass entertainment was cinema or radio – one of my favourite radio shows being Educating Archie, which was actually a ventriloquist act. A vent act on radio – work that one out!

I saw my first TV pictures on a tiny box with a fuzzy little screen, introduced by Elizabeth Cowell with the words, ‘This is direct television from Alexandra Palace …’ The local baker was the only person we knew who owned a TV set and it was so exciting to gather around it waiting for the valves to warm up and seeing the picture emerge. Little did I realize that, a decade later, I would be starring in my own show on the box.

The momentous day I turned from viewing to being viewed was 27 March 1949, in a production of The Governess by Patrick Hamilton. It was transmitted live at 8.30 p.m., and I received the grand sum of twenty-three guineas to play the part of ‘Bob Drew’. According to the BBC files I was allowed to study recently, the story all took place in Drew’s house ‘outside London, in the middle of the Victorian epoch’. The plot centred on the kidnapping of my sister, and I had to come in to the drawing room where the police had gathered and say, ‘Hello, mother! What’s going forward here?’ I never understood the line, and am sure viewers were equally perplexed by the Victorian turn of phrase.

Other cast members included Clive Morton, Betty Ann Davies, Joan Harben, Jean Anderson, Dorothy Gordon and Willoughby Gray, whom I vividly remember describing his interest in restoring model soldiers to me, and that he had a whole battalion of them. Almost forty years later, Willoughby starred as Dr Carl Mortner in my last Bond film A View to a Kill. You can’t keep a good pairing down!

Almost everything was transmitted live because TV budgets didn’t extend to the luxury of recording on expensive tape or film, but thankfully we had a couple of weeks’ rehearsal to get everything spot on and in this instance we all decamped to the cold and draughty Methodist Hall in Thayer Street, London. Our producer/director was Stephen Harrison, who guided us through the text and explained the various set-ups the camera would move through, stressing how careful we had to be so as not to get in its way, nor to be on the wrong set at the wrong time, as it would simply have spelled disaster for the whole production. No pressure then.

The possibility of an actor drying, a scene shift not working or a camera breakdown was something of which we were all aware, but tried not to think about. Electrical equipment wasn’t anywhere near as reliable as it is today and in fact during the technical rehearsal on the morning of transmission we had to wait thirty minutes for a camera fault to be remedied. Mercifully it was all right on the night.

I unearthed a couple of interesting production memos from those BBC files. One was from Evelyn Moore’s agent saying that in the Radio Times listing for the show, ‘Miss Moore’s credit should also state she is now appearing in The Dark of the Moon at the Lyric Hammersmith’. There’s nothing like an unashamed plug for one’s current project!

Another memo was from the head of programming to our producer, stating, ‘Running time is 100 minutes including a one-minute opening and three-minute interval. The budget will be a maximum of £660 for one performance and should include all costs of wardrobe, design, film, sound, artists, script copyright, orchestration, transport, hospitality and photos.’

Even in the hands of the most prudent BBC accountants, I don’t think £660 would go very far nowadays.

Of course, beaming into people’s living rooms made you ‘real characters’ in the viewers’ eyes, and many blurred that reality with drama. For example, one of my live TV contemporaries was Leonard Rossiter who was later – and most fondly – remembered for playing the miserly landlord Rigsby in Rising Damp. In one particular drama he was being examined by a doctor and, while fully trousered, had his shirt off.

‘You can get dressed again now,’ said the doctor and the dialogue continued while Len buttoned up his shirt and moved on to the next set-up.

Before the programme had ended word came through that somehow his mother, Mrs Rossiter in Liverpool, had been out to a phone box, got through to the BBC – which was no easy task in itself – and then miraculously to the production office to leave a message, ‘Len, you never put your vest on!’

Mind you, that blurring continues today, with soap opera characters often being mistaken for the actors who portray them. Mark Eden, who played villain Alan Bradley in Coronation Street, was innocently doing his grocery shopping at a local supermarket when he felt a sudden searing pain across the back of his head. He turned around to see an elderly lady swinging her handbag. ‘That’s for what you did to Rita!’ she exclaimed.

I was in great demand at the BBC and on 24 April 1950 appeared in The House on the Square as ‘John’. In fact, there were two performances, the second (or repeat) being four days later. Again, it was all staged at Ally Pally and this time for director Harold Clayton. An hour into the first performance and an electrical breakdown on the stage meant it was time for the infamous Potter’s Wheel interlude film to appear on TV screens, along with the words ‘Please bear with us while we try to restore your programme’. There were quite a few technical breakdowns in those days and so the Potter’s Wheel was pretty well known in its day. Thankfully this time it was only on for a minute and we were able to resume; just as well we were the consummate professionals.

Drawing Room Detective was, in fact, my third BBC drama opus, broadcast on 27 May 1950. In it, I played a part as well as performed the duties of Assistant Stage Manager (ASM) for the grand fee of fifteen guineas. It was a sort of whodunnit, hosted by Leslie Mitchell, in which viewers were invited to guess the person responsible for a crime.

With no further drama casting in the pipeline, I accepted an ASM role on a few episodes of Lucky Dip in June 1950, which was described as being a ‘Variety Hopscotch’. I was paid less at seven guineas this time, but it only involved a couple of days’ rehearsal at Lime Grove, followed by the live transmission from Ally Pally. It was actually rather fascinating to be part of a variety programme as the thirty minutes featured some regular comics – Duggie Wakefield and Archie Glen – along with a terrific line-up of guest artists including Julie Andrews, George Moon, Benny Lee, Lynette Rae, Jenny Lee, The Great Gingalee and a host of extras. There was also a new TV segment that excited BBC bosses, in which a member of the public chose a tune and Nat Allen’s band in the studio had to see if they could play it … If they could rise to the challenge the lucky punter received a prize of two BBC TV show tickets of their choice.

I also lent my ASM credentials to a Caribbean Miscellany called Bal Creole in which Boscoe Holder – brother of Geoffrey Holder, with whom I starred in Live and Let Die – was brought in from New York with his steel band, which, I believe, was the first time the metal dustbin-lid-type drums had ever been seen on British screens.

The Man Who Haunted Himself was one of the first films made at Elstree Studios under the leadership of Bryan Forbes. It’s now attracted a bit of a cult following, I’m told.

Being a jobbing actor I was happy to accept anything, but when the mention of a film was made I thought I’d hit the big time. The Automobile Association (AA) made a number of training films and semi-documentaries, and I was drafted in to play a patrolman, along with my old friend Leslie Phillips. I wasn’t sure it would lead to my name in lights over the entrance to the Odeon, but it was a start. The exotic location for the twenty-minute epic was a road somewhere on the outskirts of Guildford and while the crew set up the cameras behind a hedgerow on one side, I was to be found across the way, happily leaning on my motorcycle combination, dragging on a cigarette while awaiting my call to duty.

Just then, an old Austin 7 with two rather antiquated ladies in the front pulled up.

‘I say, patrolman! Patrolman!’ called the driver, with a rather strained upper-crust accent. It took a few moments for it to sink into my thick skull that she meant me and so in my full AA uniform, puffing on my fag, I ambled over.

‘Is this the road to Guildford?’ she asked.

‘Guildford?’ I pondered. ‘Well, back there I did see a sign that had Guildford on it, but I can’t remember in which direction it was pointing ...’

At that moment it obviously dawned on the old dear that there was something rather peculiar about this particular patrolman, as not only did I slouch and not salute (as a real AA man at that time would have), I was also smeared in make-up. Without taking her eyes off me, she feigned a smile, reached down with her left hand and, after a few attempts, ground the gear stick into first and kangarooed off down the road. Sixty-four years later they’re probably still circling the outskirts somewhere looking for Guildford.

Meanwhile, back at Pinewood, things were ticking over nicely with British crowd-pleaser films such as the Norman Wisdom comedies, the Doctor series, starring Rank’s biggest star, Dirk Bogarde, and (a little later) the Carry Ons.

Dirk Bogarde made most of his Pinewood films with Betty Box and Ralph Thomas. Betty, his producer, was married to Carry On producer Peter Rogers and was one of only a couple of women who had held such a role within the film industry, while Ralph – the director – was the brother of Carry On director Gerald Thomas. They were often described as the ‘royal family’ of the studio. One of the duo’s films with Bogarde was The Wind Cannot Read, in which he played a flying officer in World War II who fell in love with a Japanese language instructor. Not a lot of people know that Bogarde had a false tooth in his upper set of gnashers and wore it throughout all of his films, only ever removing it at night when he turned in and placed it on his bedside table. Every morning the first thing he did was slip the tooth back in.

On location, Bogarde was having terrible trouble sleeping and consequently, day by day, looked increasingly more haggard on set. Ralph Thomas was becoming concerned that his leading man was going to look anything but his best, and suggested Bogarde might take a sleeping pill. Bogarde wasn’t keen on the idea, but Ralph nevertheless left a couple on his bedside table and suggested if he couldn’t get off to sleep after an hour or so, he should take one.

After an hour of tossing and turning, the star finally reached over and took a pill. At three o’clock in the morning, Ralph Thomas was woken by Bogarde banging furiously on his hotel room door. The star told his director that he’d taken his advice, but after getting up to use the bathroom he had noticed that both pills were still next to the bed and, yes you’ve guessed it, the false tooth wasn’t. The next day’s schedule called for a number of close-ups of Bogarde and, understandably, panic set in. Half a dozen bottles of castor oil and a jug of disinfectant were sent up to the room ... and yes, they got their close-ups.

Which is your favourite, Simon Templar’s Volvo P1800 coupe in The Saint …

However, it wasn’t until 1961, when Cubby Broccoli and his new producing partner Harry Saltzman wanted to set up a series of spy adventures based on Ian Fleming’s hero James Bond, that Pinewood really hit the big time. Typically, I missed out on all that fun as I didn’t return to Pinewood until 1970, after hanging up my halo on The Saint at Elstree, when Bob Baker, Johnny Goodman and I set up a new series called The Persuaders!.

When Tony Curtis’s name was mentioned to me by Lew Grade as being one of the three possible co-stars for the 1971 series The Persuaders! (the other two being Glenn Ford and Rock Hudson) I was immediately grabbed by the idea. I thought Tony was a brilliant actor in films like The Sweet Smell of Success, Trapeze, The Boston Strangler and, of course, he showed his comedic skills in Some Like It Hot in which he based his English accent on Cary Grant. Incidentally, when director Billy Wilder later told Cary, he said, ‘But I don’t talk like that!’ in exactly the same way in which Tony had taken him off.

… or Brett Sinclair’s Aston Martin DBS in The Persuaders!?

Tony had worked with an impressive roster of directors, and while he rarely spoke ill of anyone, he did tell me he had a tough time on Spartacus with director Stanley Kubrick. The whole cast had endured an agonizingly long shoot, and one day Tony turned to co-star Jean Simmons and asked, ‘Who do you have to fuck to get off this picture?’

Danny Wilde and Sir Brett Sinclair doing what they did best on The Persuaders!. As you might imagine, Tony and I had a great deal of fun on and off set.

As part of the package of luring Tony to make a TV series, Lew Grade bought him a house in Chester Square in London’s fashionable Belgravia for an astonishing £49,000 – and it was Tony’s to keep. A few years later he sold it for £250,000 and thought he’d made a pretty good deal, but a couple of years after that, when he returned to England and looked at buying a similar property, he discovered the asking price was nearer £2 million.

Throughout the fifteen-month shoot, or at least most of it, Tony’s wife Leslie was pregnant. She was already ‘well endowed’, but was now even more ample of bosom. Tony had always been what you’d call a ‘boob man’, and so he liked Leslie to wear low-cut dresses that exposed as much as possible. One evening I was at his house for a party and, as his wife walked into the room, Tony said to the assembled throng, ‘Look at my darling Leslie, doesn’t she have the most wonderful tits?’

In between set-ups one day on set Tony said, ‘Dear sweet Roger, Burt Lancaster once told me that if you’re in your dressing room at the studio with a young lady and your wife should walk in, continue with what you’re doing and when you get home deny it, and say, “But they have people who look like me”.’

I was never tempted into such a situation, though a year or two later I found myself filming in South Africa, and in one scene my character was to bed a rather attractive young lady in her apartment, demonstrating his Bond-like masculinity no doubt, and in a very thick Afrikaans accent the young actress said to me, ‘I really wish there weren’t all these people around’, referring, of course, to the crew.

‘Oh, why?’ I asked innocently.

‘Because I could show you a really good time!’ I thought about Tony’s words for a split second, but that thought soon turned to my (then) Italian wife, who was sitting downstairs and who knew my stunt double was off that day!

The Persuaders! was scheduled for a twelve-month shoot but ended up taking fifteen. You see, not only did Tony like to wander off script and improvise on occasions, meaning we found ourselves taking a little longer to shoot a particular sequence, he had a total aversion to overtime.

The British Trade Unions were all powerful at this time, and the ACTT (Association of Cinematograph Television and Allied Technicians) had very strict rules about working hours, with the only exception being you could ‘call the quarter’ (an extra fifteen minutes) if the red ‘shooting’ light was on at 5.30 p.m. and you needed to finish a certain scene.

Tony got wise to this, and would never start a scene after 5.15 p.m.!

We also found it particularly difficult to persuade him to come in for looping. This is the process undertaken at the end of all movies to make sure the soundtrack is consistent in each scene or to add music.

‘But why do we need to do it?’ Tony – a veteran of twenty years in movies – asked.

‘Tony, in the last set-up in the gardens there was a close-up of me talking, and then it cut to you but an aeroplane was flying over at that point. So when we edit it together it’ll go from no background noise on me, to noise on you, to no noise on me again ... we need to re-record your dialogue,’ I explained.

‘Audiences are sophisticated,’ he replied in all seriousness. ‘They understand these things.’

Knowing he didn’t want to stay back after 5.30 p.m., when it was usual to loop any such scenes, I suggested we might do it during our lunchtime for half an hour.

‘Okay, okay,’ he conceded. ‘But I want champagne and smoked salmon in the theatre.’

The next day, he arrived at the theatre in Pinewood and a few moments later Johnny Goodman, our Associate Producer, just happened to walk in.

‘Tony!’ Johnny shouted. ‘Smoked salmon and champagne! You’ve never had it so good!’

‘Goddam son of a bitch!’ Tony shouted. ‘You’ve just blown your half hour!’ and he stormed out.

Tony was what you might call ‘very careful’ with his money, to the point you might have actually wondered if his trouser pockets were sewn up. One Christmas, we were shooting The Persuaders! over the Festive period and he invited my (then) wife and I to join him and Leslie for dinner one night. I’ll never forget it: he produced the tiniest roast chicken, which, we discovered, was not only to serve us four, but his two household staff as well. Talk about trying to pick the meat off the bones!

Just then a group of carol singers arrived outside the front door and piped up with ‘Once In Royal David’s City’. At the end of it, they rang the bell in expectation of receiving a little Christmas offering. Tony started waving his arms and screamed like a banshee, ‘Get away, get away or I’ll call the cops!’

Leslie, who obviously felt pleased at having picked up a little English, said, ‘No, Tony! It’s Bobbies, honey, Bobbies!’

His meanness was demonstrated further at the end of filming, when it is customary for the leading actors to be offered some of the items of clothing they had worn in the production. Tony took absolutely everything, and then held a sale for the crew to come over and buy it all off him!

He next called Johnny Goodman to his dressing room.

‘Well, Johnny, we’ve been working together for fifteen months and I’d like to give you something in appreciation of everything you’ve done for me.’

Johnny, being somewhat surprised at this out-of-character generosity, thanked Tony profusely – and was duly presented with a bottle of the cheapest sherry you could buy from the local supermarket.

‘Now, what shall I write on it?’ Tony pondered aloud. ‘I know ...’ and he scribbled ‘Best wishes, Tony’.

Johnny has never opened it, and often stares at it ... in disbelief.

But you couldn’t help but love Tony, he was a terrific character and a gift as a co-star.

Meanness is not an attractive trait in actors, and I remember a production accountant telling me he had been working with a certain thespian of Scottish origin and had arranged for his per diem (agreed daily out-of-pocket expenses) to be dropped in to the actor’s dressing room each morning.

‘Keep hold of it until the end of the week, would you?’ the actor said each morning. Then at the end of the week he said, ‘I don’t need it at present, so keep hold of it until I come and see you.’

A couple of months later, with filming complete, there was a stack of these little brown envelopes in the safe, and together they amounted to a considerable sum. The actor came to collect them with a large briefcase.

The following week bills started arriving from restaurants, theatres, car companies – the actor had charged everything he should have paid with his per diem to the production and pocketed the cash!

Whatever his eccentricities, though, Tony ensured that there was never a dull day when we were making The Persuaders!. Over our fifteen-month schedule we filmed in every nook and cranny of Pinewood and the adjoining Black Park.

Cubby Broccoli was a regular in the Pinewood dining room and always made a point of introducing me to his guests. He sat at the large round table – the same one that had been reserved for Emeric Pressburger all those years earlier – where he entertained backers, sponsors, royalty and visiting journalists over sumptuous lunches. It was a magical environment in which to impress visitors and inveigle finance. Stars such as Bette Davis, James Caan, Peter Ustinov, Katharine Hepburn, David Niven, Gregory Peck, Stewart Granger, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor could all be spotted at the tables. Liz would be showing off her latest jewel, and they’d talk about who was doing what next and for how much, or what offers they’d refused, or gossip about who was sleeping with whom, all often punctuated by the unmistakable laugh of Sid James and the Carry On gang on neighbouring tables.

‘How many set-ups did you get in this morning?’ Sid would shout across, inducing a sort of friendly rivalry to anyone in earshot (he’d no doubt taken side bets on it).Tony Curtis was once prompted to boast that we’d managed ‘five’.

The Carry On films were in their early days when this shot was taken in the 1960s, but Barbara Windsor and the gang were always around at Pinewood, and we enjoyed a friendly rivalry in the dining room.

‘Oh, we slipped in eight,’ Barbara Windsor chuckled back, much to Tony’s chagrin.

Meanwhile, the Carry On producer Peter Rogers locked the stage doors at lunchtime to prevent any of his artistes or crew claiming overtime.

Kenneth Williams starred in more of the Carry On films than any other actor, though he never stopped complaining about what he felt were poor scripts, terrible money and co-stars with whom he didn’t get along. However, his moaning and bitching aside, he was without doubt one of the funniest raconteurs you could ever meet. When I started on my first book tour in 2008, I was reminded of the story Kenneth told about attending a store signing in Australia – though actually he stole the story from Monica Dickens, to whom it actually happened, but we won’t let that detract from my tale.

‘Who’s it for?’ he asked the lady at the front of the queue.

‘Emma Chisset.’

He duly signed and handed her the book.

‘What’s this?’ asked the lady, looking at the inscription.

‘Your name!’ exclaimed Williams.

‘No, I didn’t say “Emma Chisset”, I asked “Ha much issit?”.’

Aside from his acting work, and borrowing other people’s stories, Kenneth also took great pride in another job within the industry, which not a lot of people know about.

When director Kevin Connor and casting director Allan Foenander set out in search of a young leading lady for Arabian Adventure in the late 1970s, they scoured the length and breadth of Britain without success, but then someone suggested they go and see a young girl at drama school by the name of Emma Samuelson. They were absolutely bowled over by the young actress and Kevin was in no doubt that he’d found his young lead. However, there was a problem: being still in drama school, Emma was not yet a member of the actors’ union Equity and as such wouldn’t be allowed to work on a British film. Ironically, the rules at the time stated that she would not be able to get her Equity ticket until she had a certain number of paid acting jobs under her belt. It was quite a ridiculous situation, but the union was all-powerful back then. All was not lost though as, in extraordinary circumstances, Equity might consider waiving the rule provided they could be convinced there was no one else suitable for the part.

Kevin, Allan and producer John Dark convened a meeting at Pinewood for the visiting Equity representative, in the knowledge it was really make or break for young Emma’s film career – and the picture. They sat solemnly waiting for the rep to arrive ... and in walked Kenneth Williams, with his trademark nostrils flaring.

The trio argued the case for casting Emma, and a stern and very serious Kenneth asked, ‘And there is no member of Equity who could play this role?’

‘No, we’ve cast extensively and Emma really is the only one suitable,’ replied Kevin Connor.

‘Then, in the circumstances, we shall offer Miss Samuelson membership and permission to be contracted.’

Despite taking his union role very seriously, he couldn’t help but then let his guard down over tea and biscuits and revert to his outrageous self, telling everyone about his recent ‘bum trouble’.

Incidentally, producer John Dark said that the name ‘Emma Samuelson’ would be too long to appear on cinema marquees and so shortened it to Samms. And so began the career of a wonderful actress.

The first Bond girl, Eunice Gayson, had a similar discussion with her employers. She was born ‘Eunice Sargaison’ and when she secured her first West End play, the producer – who paid for signage out in front of the theatre by the letter – said she must shorten her name. Funny how these things happen, isn’t it? And as for my old mate Maurice Micklewhite, his agent suggested it wasn’t the sort of name that tripped off the tongue easily, so young Maurice looked across from the phone box at Leicester Square where he was calling from and saw The Caine Mutiny was playing at the Odeon. Henceforth Michael Caine, film star, was born.

Kenneth Williams, meanwhile, had a habit of flashing his manhood around the Pinewood sets. ‘Oh no, Kenny, put it away!’ his female co-stars would moan. I think he did it more in an attempt to shock than anything else, although I did hear on one occasion that he complained to producer Peter Rogers that he had ‘grazed his penis’ on set and was sent off to see the nurse. Twenty minutes later, and with his director and co-stars waiting, there was still no sign of Williams, so Peter marched down to the nurse’s office, opened the door and saw him lying on the table naked, sighing gently, while the nurse was massaging his tool with a handful of ointment.

‘I’ll be there in a few minutes,’ replied the star, as Peter almost wet himself with laughter.

On another occasion, at a party thrown by comedy actress Betty Marsden, the hostess said to Williams, ‘Now, Kenneth, are you behaving yourself?’

‘Is my cock hanging out?’ he asked.

‘No,’ she said, cautiously.

‘Well then, I must be!’ said Kenny.

Kenneth – unlike me, of course – took great pleasure in talking about his various ailments whenever he was on the chat show circuit, such as the occasion he was in his theatre dressing room, washing his rear end in a pot, when Noel Coward sprang through the door to congratulate him on his performance. Kenneth apologized for his appearance, and said that following his last operation, the doctor had advised that he should bathe rather than use paper after visiting the loo.

‘My dear boy,’ replied the Master, ‘you have no need to explain. I had that very operation and know just how painful piles can be.’

‘Piles! Oh nooooooo,’ protested Williams, ‘I don’t have them! I have pipilles.’

Without missing a beat, Coward replied, ‘Pipilles, dear boy, is an island in the South Seas.’

I can’t write about Pinewood and not mention the biggest film never made there, can I? Cleopatra with Elizabeth Taylor in the title role, Richard Burton as Mark Antony and Rex Harrison as Julius Caesar (though that part was actually cast with Peter Finch when production commenced in 1960). So many problems plagued the film, not least the runaway budget which, at the time, made it the most expensive film that had ever come out of the studio. In fact the trouble started when the proposed leading lady, Joan Collins, was rejected by director Rouben Mamoulian in favour of Elizabeth Taylor who demanded – and got – the previously unheard-of fee of $1million for her participation.

Following that huge investment, lavish sets of previously unprecedented dimensions were constructed on the back lot, including the harbour in Alexandria (which held one million gallons of water – that’d take a few days with a bucket, I’ll bet) and the Egyptian desert, but the construction coincided with a plasterers’ strike and, in desperation, the studio took out advertising on prime-time TV to fill the vacancies. Before even a foot of film had been exposed, the expenditure had exceeded £1 million.

Then there were the 5,000 extras to accommodate with extra trains, buses and shuttles and mobile toilets that were brought in from Epsom racecourse. But the one thing the financiers didn’t bank on when they opened their wallets was the British weather. Torrential rain fell and shooting was abandoned. Worse still, Elizabeth Taylor fell dangerously ill and had to undergo an emergency tracheotomy, and Joan Collins was put on standby to replace her. But with the rain still falling incessantly, and news of Liz Taylor’s recuperation likely to be a long one, the decision was made to relocate to a warmer climate, which would help aid their star’s recovery, and so everyone shipped out to Rome to remount the production. Well, except for Finchie – he’d had enough. Rouben Mamoulian also left the production at that point and was replaced by Joseph Mankiewicz.

Spotting an opportunity to use some of the leftover sets and costumes, producer Peter Rogers made Carry On Cleo and at one point fell foul of 20th Century Fox by emulating their posters. It wasn’t the first time that had happened either, as when Peter made Carry On Spying the Bond producers raised their concerns about his poster looking similar to From Russia With Love.

While we on the Bond films had the luxury of six-month schedules and generous budgets, the Carry Ons were made for a few hundred thousand pounds and shot in about five weeks, with only occasional location work outside the studio – usually in Maidenhead. When Carry On Up the Khyber was made they used Snowdonia in Wales to double for the Afghan mountains (again no expense lavished) and at the premiere, one of the invited dignitaries sidled up to the producer and said he’d served in the Army and, ‘I remember so many of those locations in Afghanistan and India. What marvellous memories.’ Peter Rogers didn’t have the heart to tell him the truth. But that is the magic of movies.

Donald Sinden told me a great story about working at the studios, a story that typifies the ethos at the studio at that time. Donald was a familiar face at Pinewood as a Rank contract star and later on in the 1970s I worked with him on a film called That Lucky Touch. He used to love chatting about all the people he’d worked with and is a brilliant raconteur. Apparently he was in the bar at Pinewood one day, and bumped into the producer Joe Janni, who started telling Donald about a script that involved three months’ location work cruising around the Greek islands. On hearing that, Donald said, ‘Count me in!’ and didn’t even wait to read the script.

A few weeks before shooting, Janni called to say that, unfortunately, the budget wouldn’t stretch to the Greek islands. It was to be the Channel Islands instead. It still sounded good though. However, a week or so before shooting, Donald went for a costume fitting and the wardrobe man said, ‘Shame about the Channel Islands, isn’t it?’

Donald didn’t know what he meant … until the wardrobe man explained that the budget wouldn’t stretch to the Channel Islands … and the location was now Tilbury docks near London! They shot out to sea on one side, turned the ship around and shot the other way, and spent three months in those wretched docks … the magic of the movies indeed!

Another great friend in the early years was Kenneth More. Kenny and I met in 1962 when he was filming We Joined the Navy at ABPC Elstree and I was filming my first series of The Saint on the next stage. We struck up an immediate friendship and saw one another all the time thereafter. Kenny had been a huge star over at Pinewood for Rank, starring in films such as Genevieve, Reach for the Sky and Sink the Bismarck! and in 1960 Rank’s Managing Director, John Davis, agreed to release him to appear in a big-budget film at Shepperton Studios called The Guns of Navarone. However, shortly before production commenced, Kenny made the mistake of heckling and swearing at Davis at a BAFTA dinner, and in one fell swoop lost both the role (which went to David Niven) and his contract with Rank.

My dear friend Kenny More was best man on my wedding day, 11 April 1969, seen here with his wife Angela Douglas.

At the time we met, Kenny was filing for divorce from his wife, Billie, as he’d fallen in love, and wanted to be with, Angela Douglas. I was, meanwhile, in the throes of seeking a divorce from Dot Squires. It’s fair to say we both wondered if we’d ever receive a decree absolute as the legal wranglings went on for years.

Kenny and I made a pact that we would both be each other’s best man when we were finally able to remarry – he was the first, in March 1968, whereas I had to wait a little longer. In fact, I remember one time we were in Mario & Franco’s restaurant in Soho and we had a discussion about what colour our respective wives-to-be wedding dresses should be. I suggested grey for my intended … they say hell hath no fury like a woman scorned, and did I feel hell’s full fury that day!

Kenny was a shrewd man when it came to the business as, unlike some actors who think they are invincible, he knew his limitations and also what type of roles suited him. I know Sir Peter Hall suggested that he play Claudius to Albert Finney’s Hamlet at the Royal National Theatre, but Kenny declined, saying, ‘One part of me would have liked to, but the other part said that there were so many great Shakespearian actors who could have done it better. I stick to the roles I can play better than them.’

Sadly Kenny was forced to retire in 1980, when it was announced that he was suffering from Parkinson’s disease. I regret not seeing as much of Kenny as I should have in his final years, but being mainly based in Hollywood and he in London it wasn’t terribly easy.

Albert Finney was another of the great British actors of that time. I remember meeting Albie when he and his theatre-producing partner Michael Medwin were in Gstaad, though of course I had known him from his many great films. His breakthrough hit was probably Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, which was produced by Harry Saltzman, and afterwards Harry placed Albie under some sort of contract, the terms of which meant that when not employing Albie, Harry still stood to gain from renting him out.

When a call came from legendary producer Sam Spiegel, wanting to see Albie for Lawrence of Arabia, which David Lean was to direct, Harry sent him off post-haste to Shepperton. On his return Harry asked how it went.

‘He blew smoke in my face,’ said Albie.

‘What are you talking about?’ asked Harry.

‘He blew fucking smoke in my face!’ said the aggrieved star.

Apparently, Spiegel sat behind his desk at the studio smoking a big cigar throughout the interview and, perhaps not unreasonably, Albie resented it. A few days later, the phone rang and the message came through that Spiegel wanted to shoot some footage of Albie on set the following Monday, so he was obviously odds-on for the role.

‘OK, you’ll be there at 10 a.m. on Monday,’ Harry said.

Nonplussed, Albie looked straight at Harry: ‘No! He fucking blew smoke in my face!’

Later that evening Harry called Lew Wasserman, the doyen of agents and dealmakers, in California to tell him the situation.

‘Get me Finney on the phone,’ Lew barked back at Harry.

Harry had to then telephone around Albie’s various girlfriends to find out which one he was shacked up with that week.

‘Lew Wasserman wants to speak to you from Palm Springs about Lawrence of Arabia,’ Harry said, when he finally tracked him down.

Albie dutifully phoned Wasserman back. ‘Spiegel blew smoke in my fucking face!’

‘It doesn’t matter what he did!’ Wasserman argued. ‘Get your ass down to Shepperton at ten o’clock on Monday morning!’

‘But I told you, he blew smoke in my face!’

‘Look. Do you know who the hell I am?’ asked Wasserman.

‘Yes,’ said Albie. ‘You’re my fucking agent – and he still blew smoke in my fucking face!’

On another occasion Albie was appearing with Charles Laughton in a production of The Party and every time Albie started his big speech, Laughton would very visibly start scratching his nose or arse, and generally making distracting moves. Albie suffered it a few nights and then told Harry Saltzman to, ‘Tell Mr Laughton I’ll kick him into the orchestra pit if he fucking does that again.’

‘Oh will he?’ chuckled Laughton.

‘He WILL!’ Harry replied matter-of-factly.

That’s what I love about Albie, he is completely independent and speaks his mind without fear of upsetting anyone. Needless to say, he didn’t go to Shepperton or get the part of Lawrence, though it never hampered his career. Nowadays he doesn’t have an agent, he prefers to negotiate through his lawyer and you won’t find him at film premieres or awards ceremonies as he hates all that – he’ll turn up, give a great performance and then go home. That’s what Albie does. He turned down both a CBE and Knighthood, saying it ‘perpetuated snobbery’. (I guess that makes me a terrible snob?)

Back at the studio, you’d often find lots of actors and directors would zip away after a thirty-minute lunch to view rushes, which was the previous day’s film back from the labs. It wouldn’t be out of the ordinary to see a few extras dressed as centurions, or large chickens, cutting through the restaurant to the bar. Nobody flinched. It was, after all, a place of work.

Lunchtimes at the studio saw other regulars too, one being Christopher Reeve who’d walk in for his meal in full Superman costume. He was so polite and would always stop at the tables he passed to say hello to fellow diners. Many a waitress swooned after him.

The bar was quite a ‘club’ too. Often you’d find Peter Finch holding court at lunchtimes and evenings with tales of the outback and working in Hollywood. He and Diane Cilento once naughtily inserted a cigarette into the mouth of a rather expensive Laughing Cavalier-type painting on the wall, much to the annoyance of Peter Rogers, who’d just paid to have it restored. Finchie was very much the practical joker of Pinewood, hiding in cupboards to surprise passers-by, removing gargoyles from the entrance and taking them home, and jackarooing around the bar with Diane at lunchtime, rounding up the crew.

He was a wonderful character. British born, though raised in Australia, he probably received greatest acclaim for his last film, Network – for which he posthumously received the Academy Award. I believe the only other person to win an Oscar after his death was another Australian, Heath Ledger – as my friend Michael Caine might say, not a lot of people know that.

Finchie very nearly didn’t make it to his career in Hollywood, or Pinewood for that matter, as, when aged just nineteen, he almost died when he was in Melbourne for a play called So This is Hollywood. The cast all went out for a picnic one day and afterwards he and co-star Robert Capron took off for a walk to explore the Pound Bend Tunnel on the Yarra River at Warrandyte, Victoria. Finchie told me they saw a fox terrier puppy fall into the river and Capron dived in and tried to save it. Tragically the current proved too strong and despite Finchie’s best efforts to save him, Capron drowned. Ironically, the dog survived and Finchie was later awarded a certificate of merit by the Humane Society, though I don’t think he ever got over losing his friend; it weighed on his mind for the rest of his life.

In his obituary notices Finchie was invariably described as a ‘hell-raiser’ and to a great extent his drinking, womanizing and larger-than-life antics overshadowed his prolific acting career. In a poignant interview shortly before his untimely death in 1977, aged just sixty, he said:

‘I’d like to have been more adventurous in my career. But it’s a fascinating and not ignoble profession. No one lives more lives than the actor. Movie-making is like geometry and I hated maths. But this kind of jigsaw I relish. When I played Lord Nelson I worked the poop deck in his uniform. I got extraordinary shivers. Sometimes I felt like I was staring at my own coffin. I touched that character. There lies the madness. You can’t fake it.’

My next visit to Pinewood after The Persuaders! was in 1973 as Jimmy Bond. Cubby Broccoli had had any number of offers to take the series overseas, but no, he said, ‘Pinewood is my home’. It wasn’t just sentimentality, it was good business sense as the crews always delivered the very best and Cubby loved the environment.

Along with the good fortune and success, I’ve also seen Pinewood at its lowest ebb. When we went in to shoot Octopussy there was nothing, and I mean nothing, else in the studio – no other films were being made. The whole industry was in the doldrums. Word had it that had we not returned it would have closed down. Shepperton shared a similar fate, with changes of ownership and asset-strippers bringing the studio to near collapse and closure. Soon afterwards, Pinewood was forced to go ‘four-walled’ – becoming a rental facility, rather than a fully crewed studio.

In between Bond films I earned a few bob playing Father Christmas. Listening to the little ones and their expectations from Santa was a treat I couldn’t miss.

The studio quickly diversified into commercials and more TV work. The plan paid off and meant that scores of big-budget blockbuster movies all had a home in the British countryside, though at the turn of the century its future seemed unsure when in 2000 the Rank Organisation announced plans to pull out of all its film interests, including Pinewood; but a new hero was at hand to continue the Pinewood story. Enter Michael Grade.

I knew Michael of old, his uncle was Lew Grade of the Incorporated Television Company (ITC), and Michael was every bit as passionate about film and TV as Lew was, but he’s also a very astute businessman. He spotted the potential and value of Pinewood and pulled together a financial consortium to buy the famous studio. He then made an offer to Ridley and Tony Scott, the owners of Shepperton, to merge the two studios.

The place is now much bigger than it was in 1947, with twenty stages as opposed to just five, and more on-site companies and services than you can shake a stick at, but the atmosphere remains the same. It is, I have decided, pure magic.

Tod Slaughter – looks a friendly chap, doesn’t he?