Apersuader can also use the style of the lizard’s language—action, emotion, and the preferences of others. Important as these three are in influencing the automatic system, they typically work through availability and association. Action, emotion, and the preferences of others can increase the mental availability of an option and modify its associations.

We have all been told that actions speak louder than words. Certainly that’s the case for the lizard. Observers of a social scene pay close attention to the actions of participants, not their motivations. Research has shown that observers will judge the character of the participants on the basis of their actions alone, largely ignoring the constraints of the situation. Even if participants could hardly have acted any other way, observers will judge the participants by their actions. If a law student is assigned to defend a racist point of view, a point of view that observers know the law student does not hold, his defense of that point of view will still color observers’ opinion of him. This phenomenon is part of what psychologists call “the fundamental attribution error.”1

Marketers often make use of the fundamental attribution error, though they don’t call it that.

Abercrombie & Fitch was for many years a high-end brand of sporting goods and apparel—hunting and fishing in particular. In the late 1980s, The Limited bought Abercrombie & Fitch. The Limited decided to use the brand to sell apparel to young people. The Limited wanted to make Abercrombie & Fitch fashionable. How does an upscale but dated brand of sporting goods become a fashionable brand?

The Limited changed perceptions of Abercrombie & Fitch by changing the way the brand acted. No internal brand personality determined what Abercrombie & Fitch did. Brands do what they do not because of who they are, but because of who they want to become. And who each brand wants to become, of course, is a brand that makes a lot of money. The brand acted fashionably in its daring catalogue, in the media, and in the store and we observers came to see Abercrombie & Fitch as inherently fashionable despite the obvious profit motive for its behavior. For the lizard, “Behavior engulfs the field.”2 In other words, for the lizard, you are what you do no matter why you do it.

Abercrombie & Fitch couldn’t become fashionable in the eyes of potential buyers by claiming to be fashionable. No brand can effectively claim to be fashionable. Nor can a brand successfully claim to be fun, exciting, or manly. A brand can’t argue its way to those perceptions. In order to become perceived as fashionable, fun, exciting, or manly, a brand has to act fashionably, fun, exciting, or manly. People will ignore the constraints of marketing and profit. People will judge the brand on its action.

The Apple ad for its MacBook featuring 74 different MacBook decals didn’t claim that the brand or its users are fun, confident, creative, and cool. The ad just had to act that way and viewers got the message. Viewers get much more information about the brand and its users by how a message acts than by what the message literally says.

An oil company can create an image for itself as environmentally conscious by its actions. The oil company may not be environmentally conscious at all, but its actions can convince people of its environmental concern. The oil company can donate to the Audubon Society. It can speak in favor of higher mileage requirements for cars. It can paint its gas stations green. This will likely cause people to think the oil company is environmentally conscious even though the real reason for its behavior may be to get offshore drilling licenses. You are what you do no matter why you do it.

How would your candidate act if he or she were indeed compassionate, tough, honest, or open-minded? Act that way and he or she will be perceived that way and no one will question the motivation. Even a milquetoast brand can be seen as rugged if it acts ruggedly. Your option and the people who seem to choose it will be believed to be the way they act no matter why they act that way.

Belvedere Vodka provides another, but an unfortunate, example of the impact of action on perception. Belvedere’s slogan was “Always goes down smoothly.” So far so good. However, in their Facebook and Twitter ads, Belvedere superimposed this slogan over a photo of a young man with a smile on his face forcibly restraining a young woman who seems desperate to get away. Above the photo, in smaller type of a different color, the copy read, “unlike some people.” A casual reader sees Belvedere making a connection between what looks like attempted rape and the brand. Why the brand made this connection is largely irrelevant; the action looks to be attempted rape. For the lizard, you are what you do no matter why you do it.

Of course, Belvedere Vodka apologized, but the lizard pays attention to action, not apologies.

Parents instinctively use action to persuade toddlers to eat what’s good for them. Dealing with the lizard inside an adult is a lot like dealing with a toddler. Parents don’t try to explain to the toddler that the food is enjoyable. They know the toddler wouldn’t be convinced. Parents show the toddler that they themselves enjoy the food by eating some with obvious pleasure. They know that toddlers still won’t always be convinced, but they also know that action has a much better chance of persuading than explanation.

Mark Twain understood this.

Discouraged, Tom Sawyer sat down facing “the far-reaching continent of unwhitewashed fence.” Aunt Polly wanted the fence whitewashed, and it looked to Tom like he had no way out. He wanted his friends to take over the job, but when he examined his pockets for toys and trash, he saw “not half enough to buy so much as half an hour of pure freedom.”3 However, Tom had an inspiration. He would persuade his friends not with barter, but with action. Tom began to act as if he enjoyed whitewashing the fence and as if he took great pride in the finished appearance. Soon, rather than laughing at his predicament, Tom’s friends were lining up for a chance to take a turn at whitewashing.

“Behavior engulfs the field.” Toddlers don’t question their parents’ real motives for acting like they enjoy the food. Tom’s fictional friends didn’t question his real motives for acting like he enjoyed whitewashing the fence.

Action communicates with the lizard and the lizard ignores the motive behind the action.

Reciprocity serves as an entirely different illustration of the impact a person’s actions have on our judgment. Robert Cialdini of Arizona State University observed successful compliance practitioners 30 years ago. He identified reciprocity as one of the tactics they employ.4 When someone is nice to us, we feel kindly toward them even if, when we think about it, we realize their action is motivated by profit, not affection. Reciprocity is special because we not only pay attention to the behavior and ignore the motive, we feel obligated to be nice in return.

Human relationships are largely built by social exchange and reciprocity is the basis of social exchange. Social exchange is best understood in contrast to economic exchange.

Economic exchange, such as purchasing something for money in a grocery store, is precise and immediate. The checker totals up how much we owe to the penny. We pay without delay. And we leave with no debt and feeling no obligation to the store, its manager, or its personnel. Economic exchange does not lead to a relationship. In fact, it is designed to avoid building a relationship.

But social exchange, for example a dinner invitation followed by a reciprocal invitation, is imprecise and often delayed. Social exchange is designed to create a relationship. The obligation we feel to reciprocate builds the relationship.

We are preprogrammed to feel this obligation to reciprocate. It is built into our automatic, nonconscious mental system. Even if we consciously recognize manipulation, we still have an impulse to reciprocate. That is why a rug merchant in Istanbul will always offer complimentary tea before displaying his wares. We know the offer of tea is a sales tool, but accepting the merchant’s tea still makes us far more likely to reciprocate by at least listening politely to his sales pitch.

Our automatic system responds to emotion because the automatic system itself uses emotion—liking, repulsion, fear, happiness—to communicate its desires.

Researchers have extensively explored the impact of liking, or what psychologists call the “affect heuristic.”5 If we like an idea, a thing, or a person, we assume it possesses an abundance of positive qualities and a minimum of negative qualities, even if we don’t have good evidence one way or the other. Similarly, if we dislike an idea, thing, or person, we assume it possesses an abundance of negative qualities and a minimum of positive ones.6 As a result, we tend to see the world as much simpler and more coherent than it actually is. In the real world, ideas, things, and people tend to have both positive and negative qualities, but our feelings bias the way we perceive these qualities.

People on different sides of an issue have a difficult time talking to each other because of the affect heuristic. Rather than looking objectively at all the evidence, we tend to notice evidence that reinforces our pre-existing feelings. When we feel positively about a particular politician, we pay close attention to information that puts him or her in a good light. If we feel negatively about that politician, we pay close attention to information that puts him or her in a bad light. As Daniel Kahneman tells us, “Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.”7

Pampers has put the affect heuristic to good use. The brand produced a beautiful, emotional, video lullaby. A mother softly sings to her baby while charming, multi-national scenes of people making life “better for baby” illustrate her lyrics.

Why did Pampers create this video? Is the Pampers brand, in fact, warm and caring and willing to do anything to make life “better for baby”? Maybe.

Pampers is also part of a giant, worldwide, consumer products corporation with more than $80 billion in sales last year. Pampers has profit demands like every brand in P&G. Pampers is probably genuinely concerned with the welfare of babies. Surely, that is good business. On the other hand, a genuine concern for the welfare of babies is not why this video was created.

This emotional video influences our perception of Pampers. It doesn’t matter that the decision to create the video was calculated and can be justified to the corporation as improving the bottom line. It doesn’t matter that the video was done so that when people stand in the baby supplies section of their store, the emotional experience of this video will give them a little nudge in the Pampers’ direction.

Some may feel that the video is manipulative. It is. Its music and images were skillfully combined to evoke viewers’ emotion. That doesn’t matter. The video is an example of creativity and emotion harnessed to build a brand and make a profit.

Classic Hallmark ads are another good example of the use of emotion in persuasion. Everyone is familiar with the format. Whether it’s a husband giving a card to his wife, a child giving a card to a parent, or a grandchild giving a card to an aging grandparent, we know what to expect. Hallmark uses emotion to speak to the lizard and we end up fighting a tear. For the lizard, feeling the emotion is what’s important. Why or how Hallmark made us feel that way doesn’t matter.

Hallmark uses the ads as a sampling program, providing millions of people a small sample of the emotional experience of giving someone a Hallmark card. We come to associate that emotional reward with Hallmark. The company effectively uses emotion to speak to the lizard and, as a result, earns remarkable profits on cardboard, ink, and creative talent. Greeting cards may be declining in popularity, but that is because of a communication revolution outside Hallmark’s control.

Thinking of persuasion as a sampling program can often be useful. Whether we would like someone to stop smoking or go on a date with us, consider whether the message itself can provide a small sample of the emotional experience the target might expect from doing what we ask. Can the children host a small celebration in honor of dad’s decision to quit smoking, providing him a sample of the affection and gratitude he can expect from continuing to not smoke? When a young man invites a young woman on a date, can he make the invitation itself charming and amusing, providing a small sample of what the date itself might be like?

Emotional associations are better remembered. When you pair your recommended option with a quality or a person, help the target feel warm, happy, angry, or amused at the same time, the link will endure.

Sometimes attempts to reach the lizard through the use of emotion backfire. The famous Schlitz campaign, popularly known as the “Drink Schlitz or I’ll kill you” campaign, is a case in point. This campaign dates back to the time when Schlitz was a beer brand to take seriously. Each ad featured a tough man, for example a boxer or a Hell’s Angel’s type. The man was asked to switch from Schlitz to another brand of beer. He aggressively refused to give up his Schlitz and threatened anyone who would try to take it away from him. The ads were over the top, surely not meant to be taken seriously.

But people responded to the campaign, not by thinking logically that manly men really like Schlitz, and not with the emotion of liking the beer as Schlitz had hoped. Viewers responded with the emotion of fear. The ads actually communicated that Schlitz and people who like Schlitz are frightening. This campaign and several other marketing missteps led to Schlitz’s precipitous downfall.

The power of the influence of others on our choices seems to lie deep in our evolutionary past. We, like many animals, copy.

The copying instinct may be most visible in mating habits. Scientists have seen that a male becomes more appealing as a mating prospect if other females have already selected him as a mate.8

Consider the lek. A lek is a gathering of males engaged in competitive display that plays a large role in the mating habits of several species. During breeding season, males in these species gather together, each in his own small, delineated territory where he can show off for visiting females. Females wander through this display area and eventually mate with one of the males. Typically, a few of the males attract most of the females.

Scientists have studied leks to better understand how the process works. A male’s mating success seems to depend not just on his own appearance and performance, but also on females copying each other. Females are more attracted to males that have other females close by.9 Sage grouse hens are more likely to choose to mate with a male if other females have already chosen him. The likelihood of a female fallow deer or sage grouse entering the territory of a male is positively associated with the number of females already present. In a particularly clever experiment, scientists found that placing a stuffed female black grouse in the territory of a male who had failed to mate resulted in an increase in the number of females who enter that luckless male’s territory. Females are influenced by the preferences of other females.

At the human level as well, our automatic, nonconscious mental system uses the preferences of others to help us form our own preferences and even to help us evaluate how happy we are with a choice we have already made.

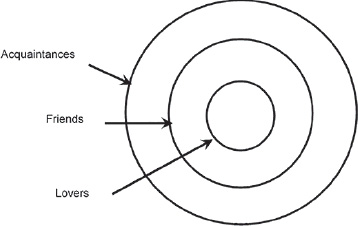

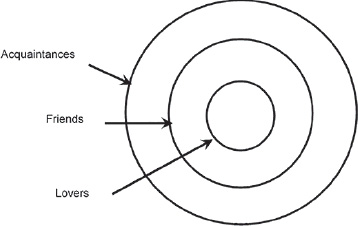

At our advertising agency, we would, for any brand, divide buyers of its product category into groups. Let’s take Nike for example. Consumers who buy athletic shoes generally know Nike. We call these consumers Nike Acquaintances. Among Acquaintances, some would consider buying Nike. These are Friends of Nike. Among Friends, some definitely plan to buy Nike and describe Nike as one of their favorites. These are Nike Lovers.

The concentric circles that follow illustrate the relationship between Acquaintances, Friends, and Lovers.

Many people expect that a brand with a very wide circle of Friends would have a relatively low proportion of Lovers among those Friends. The thinking is that a brand that has made itself acceptable to most category users must have rounded off its edges and become bland. Similarly, many people expect that, if a brand has a smaller circle of Friends, it would have a higher proportion of Lovers among those Friends because the brand had been true to a sharply defined identity. Those few Friends must see something uniquely attractive in it.

We noticed a very different pattern. Around the world and across product categories, when a brand has more Friends, a higher proportion of those Friends are Lovers. The pattern is the same for sports apparel brands in China, camera brands in Germany, and tire brands in the United States.

In China, about 22 percent of the population would consider buying Fila; that is, 22 percent of the Chinese population are Fila Friends. And about 10 percent of those Fila Friends say they would definitely buy Fila and that Fila is one of their favorites; that is, 10 percent of Fila Friends are Fila Lovers. On the other hand, about 62 percent of the Chinese population are Nike Friends. And about 19 percent of those Friends are Nike Lovers. Nike not only has many more Friends than Fila, but each of those Friends is almost twice as likely to be a Nike Lover.

If a brand has a lot of Friends, a lot of those many Friends are Lovers. If a brand has few Friends, few of those few Friends are Lovers. The pattern holds for most any category around the world. Depth of affection grows along with breadth of popularity. The feelings of all influence the affection of each. The preferences of others influence our preferences.

Andrew Ehrenberg and his colleagues have repeatedly demonstrated the practical implications of this phenomenon in buying behavior, a pattern they call “Double Jeopardy.”10 They look at brand penetration—the proportion of the population who buys the brand at least once in a time period (usually a year), and brand frequency—the average number of times the brand was purchased in the period by each of those who purchased it at all. They found that brands with higher penetration had consistently higher frequency. When more people bought a brand at all, those buyers bought that brand with greater average frequency. They found this same pattern across categories around the world.

The relationship of Lovers to Friends and the relationship of frequency of purchase to penetration illustrate the impact that the preferences of others have on how we feel and act. If a brand has a lot of Friends, each of those Friends is more likely to be a Lover. If a brand has more buyers, those buyers buy the brand more often.

To appeal to a broader range of customers, a brand need not, in fact shouldn’t, dull its distinctiveness. A great brand focuses clearly and precisely on something that many people want, and works to be better at providing that than any other brand. Everybody wants to feel like an athlete. Nike and Gatorade are better than other brands at allowing everyone to feel that way. If Nike or Gatorade watered down their athletic drive, everyone would feel shortchanged.

Laughter yoga provides a good illustration of the ability of the behavior of others to influence our behavior. According to Time magazine, there are more than 400 laughter yoga clubs in the U.S.11 In a laughter yoga session, a group of people gather together in a room, look at each other, and simulate laughing. No jokes and no humorous material are used. In fact, such material is discouraged. Soon, without the benefit of any amusing stimulus, simulated laughter turns into real laughter for some and quickly the real laughter is infectious for all. A room full of people who were not laughing becomes a room full of people who are heartily laughing through a process that completely bypasses conscious thought. Proponents of laughter yoga claim all sorts of health benefits. The health benefits may or may not exist. But it is clear that the laughter of others can cause us to laugh even if we know that those others are not laughing at anything in particular.

Social scientists remind us that we are preprogrammed to imi-tate.12 Social perception automatically results in corresponding social behavior. When we see someone yawn, we start to yawn as well. When we see someone scratch his head, we do so too. When we see elderly people, we start to walk more slowly and we become a bit forgetful.

We don’t decide to imitate. Like fish, we automatically behave like those around us.

Some social scientists feel that social influence works because we use the preferences of others to guide our choices. They say we assess an object’s value by both what we ourselves personally know of that object and by the value we see others place in it. These scientists speak of “information cascades.”13 An “information cascade” begins when what we learn from others about the value of an object outweighs whatever personal experience we have. Because we can’t know everything about every object, it is only natural that we would pay attention to how others feel. The logic of online sites like TripAdvisor reflects this reality. Five-star reviews by thousands of raters are remarkably persuasive.

In experiments with music sharing, Salgonic, Dodds, and Watts saw the effect of information cascades.14 They divided participants in their music-sharing experiments into random groups. They found that the early downloads of people in each group had a dramatic impact on the music that became favored by the whole of each group. Early downloads revealed the value others placed on specific music.

Early actors have an inordinate influence on the behavior of later actors. If you are one of the first to speak at a parent-teacher meeting, you can influence the tone of the whole meeting by making a polite comment or an angry comment. If you are seated toward the front of a theater and you quickly jump to your feet to applaud at the end of a performance, you will dramatically raise the likelihood of a standing ovation from the whole audience.

One of the easiest ways to influence the behavior of others is to prominently act the way you would like them to act. Give your seat to an elderly person on the bus and others will also. Make it clear you are not drinking because you are driving and others are likely to join you in your abstinence. Don’t underestimate the urge to imitate.

We see the power of the tendency to imitate in the persuasive technique of “scarcity.”15 Items for sale become more attractive to us if there appear to be only a few left. What is motivating to us are not the few left, but the many that have already been sold. If only a few remain, we are limited in our ability to imitate the many people who have already purchased, and this gives some urgency to our own purchase. If there are only a few left, but there were only a few to begin with, the scarcity doesn’t motivate us.

If you are or have been the parent of a teen, your teen no doubt has said they want to do something “because everybody’s doing it.” In response you probably heard yourself say, “If everybody jumps in the lake, are you going to jump in the lake too?” The influence of the preferences of others is particularly strong among teens and the others they are most concerned with are peers, not family.

Advertisers of course know about the influence of the preferences of others. That’s why ads of all sorts attempt to tap into that power with claims of “America’s favorite” or “More people choose….” Even if marketers can’t make such a claim, they use marketing to create the impression of popularity because they know the power of our perception of the preferences of others.

We discovered that the impact of the preferences of others on us is particularly strong if we believe the number of people who feel that preference is growing. If we believe both that a lot of people recycle and that the number of people who recycle is growing, we are more likely to recycle ourselves. If we believe a lot of people recycle, but we believe the number of people who recycle is declining, we are not as motivated to recycle. It seems that the lizard responds to not just the preferences of others today, but what it senses the preferences of others are going to be tomorrow.

To harness the power of the preferences of others, promise to provide what most of those others want. A brand should promise to fulfill a desire that is one of the fundamental motivations for using the category, a desire that is felt by most category users. You can then go on to explain why your brand’s way of fulfilling that desire is superior to other ways of fulfilling that desire. If your brand is an athletic shoe, promise to satisfy one of the fundamental motivations for buying athletic shoes and tell us why your way of satisfying that motivation is better. If your brand is a drain cleaner, promise to satisfy one of the fundamental motivations people have for buying a drain cleaner and tell us why your way of satisfying that motivation is better. Success in marketing follows from being perceived as uniquely able to provide something many people want.

Popularity and momentum are hard to resist. People will value your option if it seems to be popular and/or growing more popular. Even affection depends on popularity. Forget the appeal of the lone wolf unless everybody wants to follow the lone wolf’s path. People’s imitation of those around them is automatic. Point out and play up fellow travelers.

Though marketers often try to tap into the influence of the preferences of others, they sometimes run afoul of this “popularity principle” because of an exaggerated belief in the power of segmentation. The most common form of segmentation identifies groups within the marketer’s target population that show different patterns of desires. Typically, many desires, and usually the most fundamental desires, are common across all groups within a target. However, segmentation takes the focus off common desires and places the focus on minor differences in the pattern of desire.

When a segmentation study selects the reward to associate with the brand, commonly felt desires are likely to be ignored in favor of minor differences in desire. Segmentation studies, when done right, can be useful in secondary marketing to groups within the overall target, but segmentation studies are not appropriate for finding the one reward that will motivate the bulk of the target.

Consider the choice you have to make about where to get an oil change, new brakes, a new muffler, new shock absorbers, new tires, or whatever when you are not taking your car to the new car dealer. In other words, consider the consumer decision about auto aftermarket service. Midas asked people what was important in their choice. Some people said they put most emphasis on dealing with a local mechanic that they knew. Other people said they put more emphasis on price. Still others said they put more emphasis on the expected quality of the parts. This pattern continued with each group of people saying they put a little more emphasis than other people on one thing or another. By the time Midas was done, they had identified 13 different segments in the population, each segment saying what was important in their choice was slightly different from what the other segments said was important.

This analysis of the auto aftermarket decision was unfortunate for two reasons.

First, strange as it seems, people don’t know how they decide or what is important in their choice. You can find out what you need to know, but you won’t find out by asking. Chapter 6, “Never Ask, Unearth,” explains how this works.

Second, the segmentation technique took the emphasis off the most fundamental desires felt commonly across the population and put the emphasis on minor differences in the pattern of desire. Midas is an enormous company doing business with a broad cross section of the population. No one of those identified segments contained even a third of past Midas customers or a third of those people who thought they might be Midas customers in the near future. The segmentation study provided little general direction for Midas marketing.

Surely people choose Midas because they feel Midas offers the best combination of many factors like its neighborhood location, its prices, the quality of its parts, the quality of the mechanic’s work, and so forth. Picking any one of those factors or even a narrow set of those factors as Midas’s marketing’s focus would probably be a mistake. Midas needed to emphasize some more general desire that implied high performance on a broad range of those more narrow factors—something like “Midas is the choice of people who really know cars” because car experts would of course choose someplace that offered the best combination of quality of service, quality of parts, and price. Or Midas could emphasize the trustworthiness of the Midas man, implying quality, price, and fairness, allaying people’s fear of being ripped off in car repair.

As a colleague, Ned Anschuetz, advised, marketers should segment supply not demand. By that he meant that marketers should emphasize what makes their brand different from and superior to other sources of supply, but should emphasize what makes their brand the right choice for anyone who feels the need. To be successful, a brand should become perceived as uniquely able to provide something many people want.

Marketers become so involved in this segmentation mindset that they sometimes think an effective way to convince group A that they want a product is to convince them that group B rejects it. We’ve all seen attempts to convince the young of the desirability of a course of action by convincing them that the old don’t understand and certainly don’t desire that course of action. It’s the marketing version of the political idea that my enemy’s enemy must be my friend. If I’m young and old people reject a course of action, then I should embrace that course of action. But in marketing, different groups are not enemies. They are just a little different.

The short life of McDonald’s Arch Deluxe line of products illustrates the mistake marketers sometimes make in dealing with the lizard’s tendency to pay attention to the preferences of others. McDonald’s was unhappy with its kid-centered reputation. They felt they could increase business with Arch Deluxe, a line of products designed specifically to appeal to adults. As a shortcut to communicating that adults like Arch Deluxe products, McDonald’s decided to communicate that kids do not like Arch Deluxe products. The ads featured children grimacing at the sight and description of an Arch Deluxe sandwich. The short cut led into a swamp.

Think of all the foods that kids like that adults also like (ice cream, french fries, hot dogs, popcorn, cherries) and all the foods that kids dislike that most adults also dislike (Limburger cheese, castor oil, liver). Kid disapproval doesn’t imply adult approval. If anything, when kids dislike the taste of something, adults are understandably wary. The preferences of others, even if the others are children and I am an adult, influence my preferences. The Arch Deluxe was a marketing disaster.

McDonald’s subsequently realized that it did not need to worry about whether it was a children’s restaurant or an adult restaurant. The McDonald’s target is universal. McDonald’s does segment the market, but very differently from the usual market segmentation. McDonald’s realized its target shouldn’t be a specific group of people; rather, its target should be a specific facet of every person. McDonald’s is a restaurant for the child in everyone.

When we wish to persuade parents to make more healthful choices in the grocery store, logic will likely have little effect. We need to speak the language of the lizard.

Can we, for example, make more healthful choices more avail-able—that is, more physically or psychologically salient in the store?

Can we adjust the automatic associations that spring into parents’ minds when thinking about more healthful choices? Can we associate more healthful choices, not with boring compromise, but with interesting experience; not with feelings of denial, but with feelings of being a good parent?

Any communication about more healthful choices will be seen as the action of those more healthful choices. A dull, tedious message will tell parents and kids that those choices are themselves dull and tedious. An interesting message will tell parents and kids that more healthful choices are themselves interesting. The message will be seen as an action of the more healthful choices that will overwhelm other perceptions.

Can we increase, even a little, the affection people feel for those more healthful choices? Just getting healthful choices to spring more easily to mind will increase parents’ affection for them.

Can we get parents to sense the growing popularity of those more healthful choices, in effect encouraging parents to get on board?

Our reflective, conscious mental system monitors the impressions and impulses of the automatic system. Usually our reflective system is content to lay back and go along with what the automatic system suggests. But occasionally, like when we are about to tell someone to “Go to hell,” the reflective system engages and forces the consideration of other courses of action.

Our reflective, conscious mental system requires focused attention and responds to evidence and reasoned argument. Persuasion that seeks to influence our reflective mental system can be thought of as following an informational or educational model of persuasion. Facts and logic are critical. However, our automatic system never relaxes and always plays an important role making any impulse more or less appealing. We probably place too much faith in the power of the informational approach to persuasion.

The attempt to influence buying prepared food in New York City is a good example of mistaken faith in the informational approach. Obesity is a growing societal problem. More and more food is consumed out-of-home, and these food choices are believed to be contributing to the obesity problem. People are choosing high-calorie options when lower-calorie options are available. Authorities in New York City decided to do something about it. The problem, they felt, was lack of information. In 2008, the city of New York required any restaurant chain with 20 or more outlets to post the calories of all options as prominently as the price. This is a massive, natural experiment. Thousands and thousands of restaurants dramatically increased the information they provide to millions of consumers across many millions of buying occasions.

What was the impact on buying behavior? Nothing.

Christine Johnson, director of Nutrition Policy, Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control Program, NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, told a committee of the National Institute of Health on October 25, 2010, that restaurant patrons showed no evidence of a reduction in calories purchased after the introduction of the law. Elbel, et al. (2009) reached a similar conclusion. People bought just as many calories after the new law as they bought before the new law.16

We need to deal with who is in charge. With out-of-home food choices, as with many daily decisions, the automatic system, the lizard, is in charge. The reflective system is not in charge and factual information is not the answer. Rational information can have little impact on a decision that is not rationally made.

Even in the world of advertising, the rational model of the mind has long held sway. Advertisers in general and advertising testers in particular assumed the validity of a rational, linear hierarchy of effects process of persuasion. Many different hierarchies have been proposed.17 Probably the most popular hierarchy was AIDA for Awareness, Interest, Desire, Action. What all hierarchies had in common was the conviction that persuasion consisted of an orderly, linear flow from information to attitude to behavior. Gifted creators of persuasive messages knew instinctively that persuasion often didn’t work that way. The conflict between the two notions of how advertising worked led to many years of tension in advertising development.

At last, things may be starting to change, as evidenced by recent articles in The International Journal of Market Research and the Journal of Advertising Research. “Fifty Years Using the Wrong Model of Advertising” is the title of an article by Dr. Robert Heath and Paul Feldwick in The International Journal of Market Research.

“How Emotional Tugs Trump Rational Pushes: The Time Has Come to Abandon a 100-Year Old Advertising Model” is the title of an article by Orlando Wood in the Journal of Advertising Research. Both articles contrast the linear, rational model of decision-making with the automatic, nonconscious model of decision-making revealed by recent psychological, behavioral economic, and neuroscience research, and intuitively understood by gifted persuaders.

Both articles discuss the fact that the linear, rational model makes testing easier. One can easily measure whether people are consciously aware of the message, can repeat some content of the message, and have changed their conscious intention to choose the subject brand. Because most choices don’t work in this rational, linear way, such measurements are reminiscent of the drunk looking for his keys under the lamppost, not because that is where he lost them, but because that’s where the light’s good.

Why did the rational model of the mind so long dominate our thinking and our science even though our most important decisions, such as choice of spouse, or religion, or friends, are clearly not based on a rational consideration of pros and cons? Why do most definitions of persuasion speak of convincing by means of reasoned argument when most of our decisions are not reasoned decisions?

The rational model persists because decision-making feels rational.

We are simply not aware of the forces at work outside of consciousness. We don’t realize we make many of our decisions before we become conscious we have made them.

Benjamin Libet was a scientist and researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, who did groundbreaking work in the study of human consciousness. He was honored for “pioneering achievements in the experimental investigation of consciousness, initiation of action, and free will.” Libet and his colleagues demonstrated in 1983 that we consciously “decide” to act about 200 milliseconds (two tenths of a second) before acting.18 However, we have an unconscious impulse to act about 500 milliseconds before acting—that is, about 300 milliseconds before we consciously “decide” to act. This unconscious impulse likely causes both “deciding” to act and acting.

In a remarkable experiment in 2008 at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Science in Leipzig, Germany, the team led by John-Dylan Haynes also looked at the timing of non-conscious and conscious decision-making.19 Haynes’s results were even more dramatic than Libet’s.

Haynes and his colleagues had people decide if they wanted to press a button with their left or right hand. The experiment was set up so subjects could remember at what time they felt their decision was made. The scientists recorded brain activity in the time before subjects felt the decision was made. The scientists found that non-conscious brain activity up to seven seconds before the decision was consciously made could predict whether subjects would press the button with their left or right hand. The scientists knew what the participant was going to do before the participant was conscious of the decision.

Timothy Wilson is a cognitive psychologist at the University of Virginia who studies the influence of our unconscious mind on how we think, choose, and act. Wilson describes the situation like this: “We often experience a thought followed by an action, and assume it was the thought that caused that action. In fact, a third variable, a nonconscious intention, might have produced both the conscious thought and the action.”20

Some ask if the Haynes findings and the Libet findings call our free will into question. Dr. Haynes responds that the decisions were indeed freely made by the brain, just not by the conscious mind.

The lizard is in charge and we need to use the language the lizard understands—availability, association, action, emotion, and the preferences of others. In most decisions, reason plays a minor role.

When a decision is not made rationally, reasons are unlikely to change it.