Figure 11.1.Border vacuum 1. A freeway underpass makes for an uncomfortable walk. This creates a border with the urban fabric of the city. Photo by Maria Koriakovtseva. Stock photo ID: 662661706. Shutterstock.

Chapter 11

Political geography

When we view maps, one of the most salient features we see are divisions into political units, be they countries, states, counties, cities, or neighborhoods. These are some of the most important divisions that influence our lives and how we interact with places. The country we live in influences economic opportunity and political rights. More locally, housing, entertainment, and many other elements of our lives are shaped by our cities and neighborhoods. One or more of these elements can also be an integral part of a person’s identity, be it a patriotic American, a proud Texan, a die-hard Bostonian, or a through-and-through Brooklynite. Political geography is about how humans carve territory into distinct areas of control, such as these types of political units. It examines boundaries and borders and how groups exert control over space. It looks at the formation of political units, such as countries and voting districts, and how groups compete for power within and between them. It also studies the effects that political boundaries and control have on spatial interaction, such as in terms of political and economic cooperation and competition.

Political geography explores the division of space and its control at myriad scales, from the local to the global. Within cities, borders and boundaries can impact the quality of urban spaces, making some places more desirable to live in and visit and others less so. Political geography comes in many forms, from urban design to the presence of street gangs. Moving to a broader scale, political districts play a profound role in who governs the places where we live. Finally, at smaller scales, the development of states, empires, and multinational organizations influences where power is centered and to which sets of laws people become subject. Political geography thus sheds light on myriad historical and contemporary issues, such as the formation of states and empires, underlying causes of civil wars, struggles for independence, battles over voting districts, and people’s emotional ties to specific pieces of land.

Territoriality is the process of enforcing control over a geographic area. Arguably, this is one of the most basic of animal instincts, found in ants and in elephants and in just about everything in between. Of course, human culture complicates our natural instincts, but it is safe to say that territorial control for power over resources and defense is a key feature of human society. Through the control of territory, people can make use of natural resources, such as minerals and agriculture, devise policies that govern industrial and service sector employment, control space for defense against outsiders, set rules on acceptable cultural norms, and more.

Political geography at a local scale

Jane Jacobs’s border vacuums

At an urban scale of analysis, borders and boundaries are often less apparent than at smaller scales. While many maps show county and city limits, other borders exist that are less visible and widely acknowledged yet can still have profound impacts on how people relate to their cities and neighborhoods. The renowned urban writer Jane Jacobs describes development of what she calls border vacuums, places that suck vital urban life out of neighborhoods, leaving them stagnant and absent of vibrant street life. Control over these spaces is minimal, as limited use by people means few eyes on ground, limited informal supervision, and thus, often dangerous environments.

These types of borders are created by single massive land uses that stretch over multiple city blocks. Railroad tracks, large hospital and university complexes, civic centers, freeways, large parks, and industrial developments that inhibit the free flow of people through them divide the city, cutting off vital street life that makes cities interesting, productive, and safe (figure 11.1). Some borders of this sort inhibit the movement of people by preventing them from crossing, as with railways and highways. Others, such as a university campus, park, or civic center, have limited pedestrian activity at night. On the other hand, a municipal concert hall may be used at night but be mostly vacant by day (figure 11.2). In any case, street life is sucked away by these border vacuums.

Figure 11.1.Border vacuum 1. A freeway underpass makes for an uncomfortable walk. This creates a border with the urban fabric of the city. Photo by Maria Koriakovtseva. Stock photo ID: 662661706. Shutterstock.

Figure 11.2.Border vacuum 2. Large block-long developments, such as concert halls, discourage street activity except for limited performance times. This creates a minimally used border that can divide neighborhoods. Photo by Dedo Luka. Stock photo ID: 655184335. Shutterstock.

Border vacuums lie in contrast to diverse city blocks, with regular intersections that allow people to connect with other parts of the city and a variety of businesses. When people are passing through places and visiting businesses at different hours of the day, street life is more interesting and safety is enhanced through the informal control of space by myriad pedestrians (figure 11.3).

Figure 11.3.A vibrant city street in Chicago. Blocks with regular intersections and diverse businesses tie the city together, promoting movement and social interaction. Photo by Lissandra Melo. Stock photo ID: 129054737. Shutterstock.com.

Street gangs

Invisible borders and boundaries in urban areas are also created by street gangs that carve up and control space for economic activity, safety, and pride. For street gangs, territory is a key component of identity and opportunity. Within a gang’s territory, it can control illicit activity, such as drug sales, extortion, and prostitution. It also provides safety for gang members so they can move relatively freely within their territory knowing that members defend the area against intrusion from rival gangs. Gang members also see their territory with a sense of pride. Being from a particular neighborhood infers membership in a social support network with other gang members. In fact, the term used for gang and the term used for neighborhood can be the same, as when a Latino gang member talks about both as “mi barrio.”

Gang borders often lie along border vacuum areas identified by Jacobs (figure 11.4). In Los Angeles, for example, many borders follow the Los Angeles River, freeways, large industrial blocks, and other urban features that are rarely transited by the population at large. Gangs on either side of these places rarely interact, meaning that violence between them is minimal. Danger lies with invisible borders, regular city streets that serve as contested lines of gang demarcation. It is at these places, where people move freely as they navigate the city and live their lives, that violence can be most intense. Since these borders are not clearly fixed by physical features, gangs can try to push them outward and expand their territorial control. Graffiti can be used to mark gang territory, and rival gangs often write over each other’s markings in contested border areas. Violence, such as shootings and other assaults, occur more frequently in these contested border areas than within secure gang territory.

Figure 11.4.Los Angeles Police Department gang injunction map. This map shows gang territory in the central area of Los Angeles. Note how freeways can function as border vacuum areas for gangs, inhibiting interaction between them. Data source: Los Angeles Police Department.

Electoral geography

Political power in the United States is tied much closer to geography than to the popular will, given that the Electoral College ensures that presidents are elected on the basis of state results, not national ones. For this reason, the presidential candidate with the most total votes lost the election five times in US history, twice since the year 2000.

But geography is even more important for other political offices. Seats for the US House of Representatives, as well as state-level legislative positions, are based on political districts that divide states into groups of voters. But there are no fixed rules as to how these districts are drawn, meaning that battles over their borders can be nearly as intense (although much less violent) as border conflicts between street gangs. Interestingly, the art and science of drawing political districts can be more important than any candidate or political platform for winning seats.

The reason for this is that people of different political parties are not randomly distributed throughout cities and across states. Rather, as you have seen in this book, people tend to cluster together on the basis of common characteristics. Support of political parties varies depending on combinations of different socioeconomic factors, such as race and ethnicity, level of education, religious beliefs, income, and more. Democrats tend to cluster in certain neighborhoods, and Republicans cluster in others. Therefore, if political districts can be drawn that bring lots of Democratic neighborhoods together, then that party is likely to win more elections. The same holds true when Republican neighborhoods are combined in their own district.

Gerrymandering is the term used to describe the political partisan drawing of electoral districts. The term was coined in 1812 when Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry redrew state senate districts to link together a string of communities in his favor. The shape of the district was so odd that some said it resembled a salamander, thus the term gerrymander (figure 11.5). Since then, political districts with unusual shapes that favor one group over another have been said to be gerrymandered.

Figure 11.5.The original gerrymander. The 1812 state senate district drawn by Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry was so oddly shaped it was said to resemble a salamander. Thus, the name gerrymander. Image by Elkanah Tisdale; drawing first appeared in the Boston Gazette, 1812.

Two of the most common means of gerrymandering are packing and cracking. Packing involves drawing lines around communities that are likely to vote disproportionately for one party or the other (figure 11.6). When likely Republican voters are packed into a district, then Republican candidates are likely to win there. The same holds true for Democrats. If one party dominates a state, packing in enough districts ensures that one party wins control of the majority of seats, be it in the US House of Representatives or in state legislatures. On the other hand, packing can lump together most voters of a minority party, ensuring that they win only a minority of seats and are unable to exert political power. Cracking involves dividing people with similar political views into different districts, thus diluting their voting power and ensuring that the opposing political party wins.

Figure 11.6.Electoral geography: Gerrymandering. Image by author.

The US Supreme court has ruled that gerrymandering based on race is illegal. Thus, parties cannot draw boundaries to pack or crack racial minorities. However, politically based gerrymandering has not been deemed illegal, and some argue that it is a fair weapon to use in the ultra-competitive world of politics. When a party wins enough power at the state level, some believe it should redraw boundaries to benefit it in future elections. The future of political gerrymandering was being contested in 2017, with the US Supreme Court evaluating its legality.

Given the persistence of gerrymandering in US politics, what have the results been? Often, the popular vote for one political party has little to do with the number of seats that it controls. For instance, in 2012, New York Democrats won 66 percent of the vote for the House of Representatives. However, due to House district boundaries, they won 78 percent of the seats. Thus, the Democrats’ political power in the House was larger than if seats were allocated according to the popular vote. But then, in Pennsylvania, the Republicans held the advantage. There, in 2012, Democrats won 51 percent of the popular vote but held only 28 percent of House seats; over half of the state voted Democrat, but the party controlled less than one-third of House seats.

Another impact of gerrymandering is more extreme with uncompromising political candidates. Landslide victories are more common in autocratic societies than in true democracies. This means that for a political candidate, the greatest threat comes not from the opposing political party but from a primary challenger from the same party. A centrist Democrat or Republican, one who understands the concerns of voters of all political stripes and is willing to compromise to pass legislation, can be outflanked by a candidate from the same party who promises to stick to the party line and take no political prisoners. Given that primary elections tend to draw more partisan voters, the more extreme candidate is likely to win. There is no incentive to win the votes of people from the other party when their numbers are miniscule in your district. Their votes just don’t matter. And in fact, many political-minority voters in gerrymandered districts know this and do not even bother to vote, reducing political participation and leading to greater voter cynicism that the system is rigged. The end result is representatives who promise to legislate only along party lines. Compromise is seen as surrender, radical political views are held, and legislative inaction becomes the norm.

Go to ArcGIS Online to complete exercise 11.1: “How gerrymandered is your congressional district?”

States and nations: Spatial distributions at a global scale

Moving to a broader scale, political control of territory has evolved into what we now call states. All the earth’s land, except for the internationally managed Antarctica, is now under sovereign control of a state. But this was not always the case. For most of human history, small tribes and clans controlled areas of land without fixed borders. People moved relatively freely, and many places were not under regular control by anyone. With time, however, the advantages of uniting into larger political units became clear. A more centralized political hierarchy could marshal economic and military resources for defense, conquest, and economic growth. People would pay taxes to the centralized government in exchange for safety. These revenues could then be used to finance armies, which defended territory from outside invaders and conquered and incorporated new lands. Revenues could also be used for economy-enhancing infrastructure, such as large irrigation systems for agriculture and road networks for trade.

The city-state was the earliest type of state, consisting of a sovereign area with an urban core and surrounding farmland. Around 4000 BCE, city states first appeared in Mesopotamia, within modern-day Iraq. The benefits of this type of political control of territory proved so useful that it appeared independently in many other places as well. Tenochtitlan, at modern-day Mexico City, formed as a city-state, while numerous Mayan city states also developed in Mesoamerica. Athens and other city-states formed around the Mediterranean.

Over time, some city-states gained strength and expanded their influence over wider areas. This led to the formation of the next level of state, the empire. Empires exerted political and economic control over multiethnic territories well beyond their core urban area. These, too, formed independently in different areas, including the Aztecs and Incas in the Americas, the Romans around the Mediterranean, the Persians and Ottomans in parts of Asia and the Middle East, and more.

While there is no single definition, the modern state generally possesses several distinctive features. First, it has a territory with fixed boundaries. Within that territory, a government administrative apparatus manages and controls activity. Two of the most important of these activities are the ability to raise tax revenues and a monopoly on the use of force. Through taxes, the state provides security and facilitates economic growth. A monopoly on violence means that only the state has the right to enforce rules, including the right to detain and punish offenders. No other individual or group has the right to use violence, and those who do face sanction by the state. In the common vernacular, the term state is typically synonymous with country.

The concept of the modern state is often seen as originating in Europe after the Middle Ages. From there, it diffused worldwide, initially via relocation diffusion with European colonialism in the Americas, Africa, and Asia, and then through contagious diffusion as additional territories near colonial states consolidated. Thus, by the end of the twentieth century, the state had become the nearly universal form of political organization.

When discussing the formation of states, it is essential to differentiate the idea from a nation. A nation refers to a group of people with a common history, culture, religion, language, or homeland. The people of a nation have a common identity and view themselves as part of a single, distinct group. This contrasts with a state, which is a political entity that may or may not have a citizenry with these common characteristics. A nation may lie completely within a state or be split among different states. These terms are somewhat confusing given the way in which we commonly use them; the United Nations is actually an organization consisting of many states, not nations.

If a state is a political unit with a government and fixed territory, and a nation is synonymous with a unified cultural group, then a nation-state is a place where cultural and political boundaries are largely one and the same. It is a place where a people exercise sovereign self-government without the imposition of power by another state. In its strictest interpretation, the nation-state consists of a single homogenous people living within a single state. However, this situation is rare. States encompass diverse populations, and perfectly aligned borders that correspond with both a state and single cultural group exist in theory more than in reality. A handful of countries come close to meeting this definition; examples are North and South Korea, where nearly all residents are Korean, and Egypt, where nearly everyone is Egyptian. In the case of pure nation-states, the people have long histories of occupying the land, speaking the same language, practicing the same religion, and following the same customs. They are united, and their national identity matches that of their state.

More commonly, nation-states are actively created. By promoting a national language, common literature, music and folklore, historic events and personalities, and more, countries build patriotism and national pride that tie people together. This is often done through the educational system, where national history is taught that stresses the commonalities of people within a country and builds solidarity. Most Spaniards, French, Americans, Mexicans, Brazilians, and others will identify themselves as members of their corresponding nation-state. It is typically their highest-level identity, even if they have subidentities tied to race, ethnicity, religion, social class, or some other group (figure 11.7).

But while nation-states with diverse populations attempt to build national unity and pride, tensions can exist when strong national identities are held among minority groups. Multinational states are states with two or more national identities. Often, but not always, these national identities can be superseded by an overarching identity with the nation-state. In the Americas, for instance, serious movements for national sovereignty among minority groups are limited, yet still exist. Indigenous groups from Chile and Argentina in the south, through Central America and Mexico, and into the United States and Canada periodically form movements for more autonomy in their ancestral lands. In Europe, Spanish identity is challenged by the Basque and Catalan people, who have distinct languages and desires for independence. Aside from Egypt, in much of the Middle East and North Africa, nation-states struggle to maintain cohesion among people who identify more with their ethnic or religious group than with the state in which they live. Nation-states are further challenged by multistate nations, where the traditional homeland of a people is split between different countries. The Kurdish people, for instance, occupy parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Likewise, the Basque people are split between Spain and France.

Figure 11.7.Mexico’s Revolution Day. National unity is created and reinforced through festivals and the teaching of historical events. Photo by Byelikova Oksana. Stock photo ID: 523997776. Shutterstock.com.

In some cases, a people do not belong to any state, making them a stateless people. Some argue that the Kurds are a stateless people because they do not have their own state of Kurdistan. However, nearly all do have citizenship in their country of residence, be it Turkey, Iran, Iraq, or Syria. The Rohingya people in Myanmar, on the other hand, are one of the largest truly stateless people (figure 11.8). They are a Muslim minority living in Buddhist-dominated Myanmar who have been denied citizenship for generations. Their lack of citizenship results in discrimination, lack of government services, and in 2017, brutal forced eviction into Bangladesh at the hands of the Myanmar military. The Haitians in the Dominican Republic are another example of a people left stateless. In 2013, the Constitutional Court of the Dominican Republic ruled that those born in the country to undocumented parents were not entitled to Dominican citizenship. What made this decision especially draconian is that it was applied retroactively to 1929, leaving thousands of people with Haitian descent instantly stateless. This ruling deprived them of the right to work, travel, own land, attend school, and receive health care. Some migrated to Haiti, lacking official documents in both countries, while others continue to risk deportation or violence from vigilante groups as they stay in the Dominican Republic.

Figure 11.8.Stateless people: The Rohingya. Members of Myanmar's Muslim Rohingya minority in Bangladesh. In 2017, thousands were violently forced from their homes in Myanmar, where they have lived for generations despite having no citizenship rights. Photo by Sk Hasan Ali. Stock photo ID: 714606577. Shutterstock.com.

State borders and boundaries

One of the essential components of the nation-state is fixed territorial borders. Because of this, state borders are the most commonly recognized boundaries in the world, subject to international law that recognizes the sovereignty of territory within them and attempts to adjudicate their location when disputes arise. Their level of permeability varies significantly; in some cases, the flow of people and goods through them is extremely fluid, while in other cases, it is nearly impossible. Thus, borders can be points of tension between restricting flows for security and facilitating flows for economic opportunity. For instance, goods and people can flow relatively easily through most of Europe as part of its integration since the end of World War II. In contrast, waits to cross the border from Mexico to the United States can take hours as US Customs agents interview and inspect all people and vehicles entering the country. While the border between the United States and Mexico is hardened to keep out contraband and unauthorized immigrants, other borders are hardened due to animosity between neighboring states. This can be seen at border crossings between India and Pakistan as well as at the most secure border in the world, that between North and South Korea (figures 11.9 and 11.10).

Figure 11.9.The India-Pakistan border. Ongoing mistrust and rivalry between these two countries has resulted in a heavily fortified border. Photo by Pavel Chepelev. Stock photo ID: 760379995. Shutterstock.com.

Figure 11.10.The South Korea–North Korea border. This is arguably the most heavily fortified border in the world. The demilitarized zone is four kilometers wide, with US and Korean troops on the south and North Korean troops to the north. Land mines, watch towers, razor wire, and electrified fences divide the two countries. Photo by Meunierd. Stock photo ID: 135695417. Shutterstock.com.

Borders have been described in various ways. Those that existed prior to development of most of the cultural landscape are known as antecedent boundaries. Often, these are based on physical boundaries. Clearly, the great oceans have acted as physical boundaries that predate human settlement, but other physical features can also divide people and states. The Andes Mountains have separated the people of South America for centuries and now form the border between states such as Argentina and Chile. The Saharan Desert has also served as a boundary between the Arab states and cultures of North Africa and the people of sub-Saharan Africa.

While there are numerous examples of antecedent boundaries, most borders today can be described as subsequent in that they were drawn after human settlement. As nation-states replaced earlier city-states and empires, their borders were drawn with the goal of encompassing people with common national identities. Sometimes, physical boundaries served as natural places for borders, such as the Rio Grande between Mexico and the United States, and the Pyrenees Mountains between Spain and France. Other times, borders are based on cultural boundaries. The modern borders of Poland, for instance, encompass a population that is over 96 percent Polish, with other groups such as Germans and Ukrainians largely in their own nation-states on either side. Likewise, Czechia and Slovakia are divided along ethnolinguistic lines.

In addition to physical and cultural borders, some are geometric. Geometric borders are those drawn on a map that do not account for physical or cultural features on the ground. Rather, they form straight lines and sharp angles that cut across the landscape. One of the first geometric boundaries was drawn with the Treaty of Tordesillas in the late fifteenth century. This treaty was an agreement between Spain and Portugal that divided the New World along a line from north to south at about 46 degrees longitude. All land to the west was to be under Spanish control, and all land to the east was to be Portuguese (figure 11.11). While the line did not stick as a boundary, it did set the stage for Portugal to control the eastern portion of South America now known as Brazil, while Spain gained all Middle and South American lands to the west.

Figure 11.11.The Treaty of Tordesillas. Data sources: Esri, HERE, Garmin, NGA, USGS.

Another geometric border lies at forty-nine degrees latitude between the United States and Canada. This border was established in the nineteenth century in uncharted lands of the western half of North America, running from Minnesota to Washington. Conflicts between natural physical boundaries and geometric boundaries are seen in a couple of locations, where small protrusions of land are attached to Canada but lie in US territory south of the forty-ninth parallel (figure 11.12).

Superimposed borders are those drawn on the landscape by outside powers. They often follow physical features and geometric lines. In theory, they can also follow cultural boundaries, but in reality, they tend not to. Certainly, borders such as those under the Treaty of Tordesillas and along the forty-ninth parallel were superimposed in the Western Hemisphere with no consideration made for the Native American nations that existed throughout the region.

Figure 11.12.Geometric border: 49th Parallel. Data sources: Esri, HERE, Garmin, NGA, USGS, NPS.

Superimposed borders dominate the regions colonized by European powers and can be clearly seen in much of the Middle East and Africa. There, land was divided among European states searching for raw materials to feed their industrial growth, with consideration of local cultural groups an afterthought at best. In Africa, formal boundaries were negotiated by Great Britain, Germany, Belgium, France, and Portugal at the 1884 Berlin Conference (figure 11.13). This conference, which took place in Berlin, Germany, clarified boundaries that were being superimposed on Africa as part of Europe’s Scramble for Africa. Of course, no African leaders were invited to this conference. Boundaries split some unified African cultural groups into different colonial territories and combined some rivals into a single territory. This disrupted African society and laid the groundwork for later civil and interstate conflict.

Figure 11.13.The Berlin Conference and the Political Division of Africa. Explore this map at https://arcg.is/j5zmW. Data source: Vogt, Manuel et al 2015 and Wucherpfennig et al, 2011.

Go to ArcGIS Online to complete exercise 11.2: “Borders and boundaries.”

Location, shapes, and sizes

Size

Geographers have studied the role that basic geographic characteristics of size, location, and shape play in state viability. In terms of size, Russia, the largest state, covers over seventeen million square miles, while tiny Monaco, the smallest, covers just two square miles (table 11.1). The size of a state can potentially impact its economic viability in a couple of ways. First, size can influence the amount and diversity of natural resources available for economic development. Larger states are more likely to have more of these. For instance, Russia has oil, natural gas, a wide range of minerals, wood products, and agricultural land to grow its economy and feed its population. The same is true for the United States, Canada, Brazil, and other large states. On the other hand, small states can have very limited natural resources. For instance, Monaco has none, while the island state of Tuvalu has only fish and coconuts.

Second, size can impact ease of self-defense. During World War II, Nazi Germany was able to easily conquer the majority of Europe, which consisted of small- and medium-sized countries. However, when it came to Russia (which at the time was the core of the even larger Soviet Union), the Nazis met their match. Russia’s larger population meant that it could fight a war of attrition, sending millions to their deaths as they held the line again Nazi offenses. At the same time, its size allowed for its industrial production facilities to be moved eastward into the Volga region, the Urals region, and Siberia, beyond the reach of German forces. This allowed the Soviets to maintain industrial production to supply weapons and equipment to its armed forces.

Table 11.1.State size: Large to small. Data source: CIA Factbook.

But while size matters sometimes, it is not always the case, as some microstates have highly successful economies. While Monaco has no natural resources, it has one of the highest per capita incomes in the world, based on banking, insurance, and tourism. The same is true for Singapore, which focuses on global trade, business, and finance, and for other small, resource poor yet affluent states such as Lichtenstein and Bermuda. In all of these cases, a lack of size and natural resources was compensated with development of human resources through education and ties to the global economy.

Location

A key locational difference lies between states that are landlocked and those that are not. Landlocked countries are those with no access to open ocean. In a global economy that relies heavily on oceangoing trade, this can present a massive disadvantage. There are forty-five of these countries in the world, and most of them are poor (figure 11.14). In fact, ten of the twenty lowest-scoring states on the 2016 Human Development Report are landlocked. While many of these are poor because they are located in sub-Saharan Africa, they still have even lower GDP per capita levels than adjacent ocean-facing neighbors.

The reason landlocked countries typically have lower levels of development is that trade costs are higher without direct ocean access. This happens in several ways. First, a landlocked country must rely on transport infrastructure of a neighboring country. Goods must be moved to port along highway or rail, but there is no incentive for the transit neighbor to improve those infrastructures merely to benefit the landlocked country. Then there are bribes and delays associated with crossing borders. Corrupt customs officers at ports and border crossings can demand bribes in exchange for goods passing through. And even when agents follow the rules, there is more red tape in the form of documents and clearances to move goods from port to a landlocked country. This both slows the flow of imports and exports and increases their costs. Ultimately, these barriers to trade limit investment, since companies are reluctant to put resources into places where the costs of moving goods will be higher. Furthermore, with fewer connections to the wider world and lighter flows of goods, people, and ideas, innovation tends to be limited in landlocked states.

Figure 11.14.Landlocked countries. Explore this map at https://arcg.is/Xrb0y. Data source: World Bank.

Only a handful of landlocked states are highly developed, and all of them lie in Europe. Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, and others do just fine despite their lack of ocean access. This is due to the high quality of transportation infrastructure within Europe; a lack of corruption, and affluent, well-integrated markets within the region that landlocked countries can interact with.

Shape

Just as states come in all sizes, they come in all shapes as well. Some are compact, taking the shape of something resembling a circle. France, Uruguay, and Ethiopia have this form (figure 11.15). In theory, a compact state is easier to administer, since transportation linkages and administration from a central capital city can reach surrounding territory in all directions. Elongated states, in contrast, are long and thin. Chile is the most extreme example of an elongated state, stretching over 2,500 miles from north to south, with an average width of only about 100 miles. Panama and Norway are also described in this way. Unlike compact states, elongated state can be difficult to administer, since territories at each extreme can lie far from capital cities. Another type of state that can be difficult to administer is the fragmented state. This type of state is broken into many pieces, such as the multi-island states of Indonesia, with over 13,000 individual islands, and the Philippines, which consists of over 7,000 islands. Perforated states have “holes” in them that are occupied by other states. South Africa is a perforated state, encompassing the small, diamond-rich state of Lesotho. While this shape is not typically a problem for the perforated state, it can be for the smaller enclosed state, which faces the challenges of being landlocked.

Figure 11.15.The shape of states. Data sources: Esri, HERE, Garmin, NGA, USGS.

The fifth common form for states is prorupted or protruded. These states have small pieces of territory that protrude out from the main mass of land like small arms. Thailand is a prorupted state, with a long southern protrusion along the Malay Peninsula. Often, the reason behind a prorupted state is to allow a small piece of land to access an important geographic feature. Namibia, for instance, has the Caprivi Strip, which reaches eastward to the Zambezi River. It was incorrectly thought that the Zambezi River was navigable and would provide access to the eastern coast of Africa. However, it was later discovered that downriver were the Victoria Falls, making navigation impossible. In the case of the Democratic Republic of Congo, a small stretch of land reaches west, giving access to the Atlantic Ocean.

Go to ArcGIS Online to complete exercise 11.3: “Location: The economic consequences of being landlocked.”

Number of countries in the world

After reading about the characteristics of states, you may ask, so how many countries are there? It seems like a straightforward question, but in reality, it comes down to who you ask. There are 193 member states of the United Nations, which many view as the official countries of the world. However, not all agree.

The United States recognizes 195 states, those of the United Nations, plus the Holy See, which holds the Vatican City, home of the Catholic Church, and Kosovo, a region that has declared independence from Serbia in the Balkans region of Europe.

Then there is Taiwan. Many products are labeled “made in Taiwan” and thus many assume it is an independent state. However, the official stance of the United Nations and United States is that it is a province of China. In fact, only twenty states in 2017 recognized Taiwan as independent. China sees it as a renegade province, the result of China’s civil war from 1949, and insists on a “one China” policy, where Beijing is solely in charge of both the mainland and Taiwan. Diplomatic competition between China and Taiwan has resulted in countries switching which of the two they recognize. In 2017, Panama switched sides, ceasing to recognize Taiwan in order to build stronger relations with a globally rising China.

Figure 11.16.Self-proclaimed states: Western Sahara and Somaliland. Data sources: National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, HERE, UNEP-WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, increment P Corp.

Recognition of Israel and Palestine is another area of intense debate among states. Israel, a member state of the United Nations, is not recognized by roughly thirty other UN member states. These are primarily Arab or Muslim states that support the Palestinians. In contrast, over 130 UN states recognize non-UN member Palestine as independent, the United States being one notable exception.

The list goes on, with many places claiming sovereignty but receiving little international recognition. Somaliland says it is independent from Somalia, while Western Sahara has declared independence from Morocco. Another half dozen self-declared states can be found around the Caucuses region and Ukraine. Some cases for sovereignty are stronger than others, reflected cartographically on some maps. For instance, the National Geographic basemap in ArcGIS Online includes both Somaliland and Western Sahara, although with notes that they are not internationally recognized (figure 11.16).

Exercise of power within states

Unitary and federal states

One of the key defining points of the modern nation-state is that the government regulates all activity within its formally recognized borders. This is often described as a monopoly on violence, where only the state has the right to enforce rules and exact punishment. Therefore, governments organize political control within their borders into two general categories: unitary states and federal states.

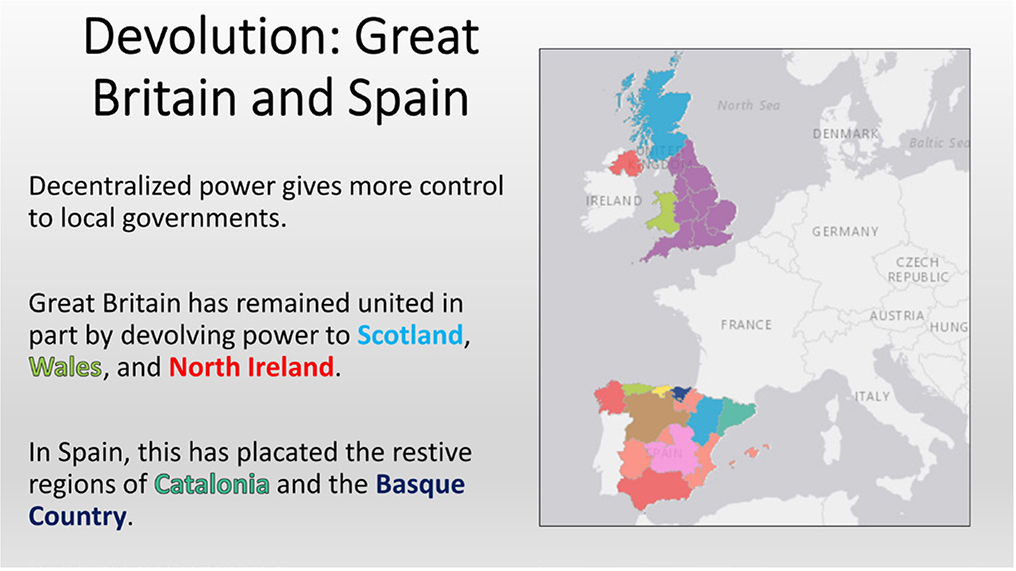

Most countries are unitary states, where power is delegated from a central government. In many cases, regulations and policies are made centrally and apply to all national territory. This can include everything from education standards, environmental regulations, labor rules, tax policy, and more. In some cases, power can be devolved to a subnational regional level, but the central government retains the right to revoke those rights. Regional political leaders can be appointed by the central government or elected to office by the local population. The United Kingdom’s central government in London allows for substantial autonomy in Scotland, Wales, and North Ireland. Each of these countries has its own elected parliament or assembly and regulates a wide range of activities, including education, health and welfare policy, transportation, agriculture, and more. The British central government, in turn, retains control over issues such as immigration, foreign policy, and taxes.

A smaller number of countries are organized as federal states. In federal systems, there is a sharing of power between a national government and subnational governments. Unlike in unitary states where some regional autonomy is allowed, in federal systems, the division of power is codified as a permanent relationship that cannot be revoked by the national government. Typically, federal states are larger and/or multiethnic. For instance, seven of the eight largest countries in the world are organized as federal systems: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, India, Russia, and the United States. China is the exception in this group. By establishing subnational power structures, large and diverse areas are more easily managed. Diverse cultures, be they linguistic, religious, ethnic, or something else, are less likely to feel that a central authority is interfering with their rights. Switzerland, for instance, is a federal state divided into twenty-six cantons, each with its own constitution, legislature, and court system. Prior to Switzerland’s formation as a single state in 1848, each of the cantons had existed as a sovereign entity, with one of four dominant languages: German, French, Italian, or Romansh. Thus, it was natural to maintain a high level of independence for each.

Nigeria in West Africa is another example of a federal state. Formed as part of Great Britain’s colonial occupation in the region, it consists of over 250 distinct ethnic groups. It is religiously diverse as well, with about 50 percent Muslim, dominating the north, and 40 percent Christian, primarily in the south. Due to the difficulty of managing such diversity, the country was divided into three regions upon independence in 1960. Since then, there have been numerous revisions to the federal structure, with thirty-six states as of 2017. A federal structure has allowed for accommodation of cultural differences. For instance, the Christian south has a legal structure based on English common law, while Muslim northern states base their legal systems on Islamic Sharia law.

Authoritarianism and democracy

When studying states, one of the most important aspects is the relationship between rulers and citizens. Governments control activities within their borders, but there are different ways in which power can be exerted. One way of viewing the relationship between rulers and citizens is along the spectrum from authoritarian to democratic.

Authoritarian regimes concentrate power. This power can be in the hands of a single dictator or a single group of leaders or political party. It is not subject to any external controls, whether from a political opposition or laws. Dissent is not allowed, and control is typically enforced with state secret police. Sometimes, authoritarian regimes will paint a façade of freedom, through written constitutions, parliaments, or elections, but these hold no real power. For instance, the authoritarian state of North Korea incorporates the façade of liberty in its official name: The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Likewise, presidential elections in Central Asia’s Kazakhstan in 2015 gave nearly 98 percent of the vote to the incumbent president, hardly a sign of a free election.

On the other end of the spectrum is democracy. With democratic systems, power is shared among different competing groups. Political parties have the right to form, and elections are held without influence from the government in power. A free press is allowed and is not subject to government restrictions. The judiciary is independent and makes decisions based on the law, not political considerations. Civil liberties are upheld for the population, and while decisions are made by majority vote, minority rights are protected. The majority is held in check from a “winner takes all” view of power.

Of course, most states lie somewhere along the spectrum from pure authoritarianism to perfect democracy. The independent think-tank Freedom House makes an annual ranking of countries based on their degree of political rights and civil liberties, placing them along a spectrum from free to not free. This ranking is based on a number of variables, including a fair electoral process, allowance for political pluralism, transparent government decision making, freedom of the press and religion, the right to form political and labor groups, judicial independence, and protection of individual rights.

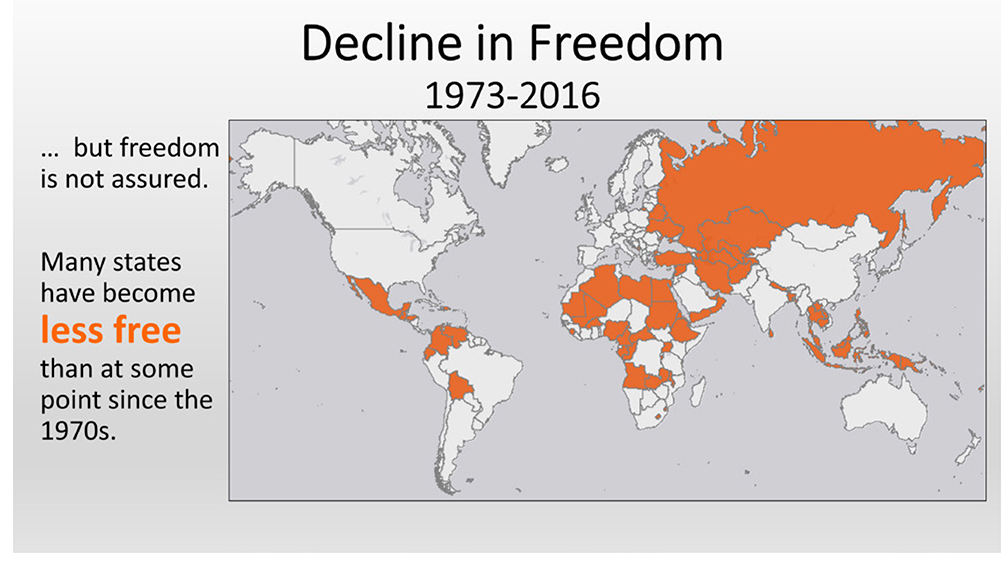

With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the trend toward democracy made great strides. In 1986, 34 percent of countries were considered free, but by 2006, the number had risen to 47 percent. At the same time, not-free states fell from 32 to 23 percent. Gains were made in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where Soviet authoritarianism ended, as well as in regions such as Latin America, where military governments ceded power to democratically elected ones (figure 11.17). But recent years, unfortunately, have seen a backslide. By 2016, the share of free countries had fallen to 45 percent from 47 percent, while non-free countries rose to 25 percent from 23 percent (figure 11.18). And, in many cases, even countries that did not slip to a lower category saw a decline in overall levels of political and civic freedom.

Some of the shift toward authoritarianism has been in countries where democratically elected leaders consolidated power and then stifled opposition. In regions across the globe, such as Turkey, Russia, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Tajikistan, and many others, laws were changed allowing leaders to remain in power well beyond previously established limits. In turn, they have managed to effectively remove opposition parties, vastly restrict press freedom, censure social media, and imprison rivals.

When the Soviet Union ended in 1991, there was much talk among political analysts about the triumph of liberal democracy. But it turns out that the celebrations were premature. Russia was considered partially free from 1991 to 2004 but then dropped to the not-free category after that. This drop corresponded with President Putin’s consolidation of power. He was first elected in 2000, then reelected in 2004. In 2008, being ineligible to run for a third term, he took the role of Prime Minister, placing another “symbolic” candidate in the role of president. In 2012, he once again was elected president, and he won the 2018 presidential election with 76 percent of the vote, cementing a solid twenty years in power.

Putin has managed to retain power through a combination of media control, patronage, and intimidation. He has managed to destroy the free press, shutting down independent TV news outlets and exerting strong influence over those under state control. While the internet has proven harder to totally control, Russia under Putin has managed to successfully manipulate it to his benefits. There are official state-run “trolling factories,” where false information is produced for blogs, video and newspaper comments sections, and social media posts. The idea is to create so much inaccurate and contradictory information that people decide no media can be trusted. Once people think that all of the information they receive is untrustworthy, then the government can say anything it wants without any regard for the truth.

Figure 11.17.Political freedom and civil liberties, 2016. Data source: Freedom House.

Figure 11.18.Decline in freedom, 1973−2016. Data source: Freedom House.

Through patronage systems, Putin channels government contracts to allies and cuts off those who oppose him. This has created a loyal class of multimillionaire businesspeople who benefit from his authoritarian rule. Then there is intimidation and violence. Political opponents have been jailed, and journalists and other opposition figures have been shot on the street and even poisoned in places as far away as London.

Unfortunately for those who support liberal democracy, Putin and other authoritarian leaders have followers around the globe. Nationalist and populist groups in solidly democratic Europe, such as France, Britain, Italy, and Austria, have an affinity for Putin and have consulted with Russian government officials. China is gaining influence globally as well, offering investments in countries from Latin America to Africa and Asia in exchange for closer political ties. Some governments are happy to participate, since China does not push for human rights and transparency as conditions for investment, as many Western democratic governments do.

State and territorial stability

Nation-states function only as long as those within their borders agree to cooperate with each other and the established national government. A state can have a name, a government, international recognition, and fixed boundaries, yet still be subject to territorial instability. Some states are stable, lasting centuries, while others fracture into competing groups and civil war. These results come from different forces that bind countries together or tear them apart.

Centripetal forces

Forces that bind places together are known as centripetal forces. In order to be stable, a state must have a raison d’être, or reason for being. It must have something that draws people to see members of a country as their in-group. In other words, the people of a state must see themselves as a nation, a single group with a common past and common future. Sometimes, the centripetal force is a common language or religion. Pakistan has Islam that binds it together (notwithstanding some militant terrorist groups), while Poland has the Polish language. Ethnicity can also bind a country together, although ethnicity is typically tightly bound with language and/or religion.

More important than religion, language, and ethnicity, however, are common values and ideals. These centripetal forces are larger than any single cultural group and can serve to tie people together as a nation despite other cultural differences. As stated previously, national identities are often created after state boundaries have been established. The United States has been able to absorb people from around the world and turn them into Americans. This successful integration is based on a common belief in ideas such as democracy and individual rights, which immigrants have absorbed and embraced for centuries. Great Britain was successful in building a British national identity from disparate groups in England, Wales, Scotland, and North Ireland. Likewise, French kings established effective control over areas with distinct languages, ultimately consolidating them into a French national identity. Through belief in and acceptance of common political ideologies, historical events, and heroes and through trust in institutions, states can be transformed into nation-states, bound by these powerful centripetal forces.

Devolution of power can also serve as a centripetal force in culturally diverse countries. It consists of granting power to regional governments at the expense of the central one. Be it a unitary or a federal state, when decision making is decentralized, geographically based resentments can be mitigated. Devolution has held the four nations of Great Britain together (as of 2018, at least). Likewise, Spain has been able to keep the restive Basque Country and Catalonia within its control by allowing its seventeen autonomous regions to run their own regional governments, with police, education and health systems, environmental regulations, abilities to tax, and protection of regional languages (figure 11.19). Canada is divided into ten provinces, with Quebec recognized as an official nation with French as its official language. Similarly, in the United States, dense urban states on the East Coast, sparsely populated prairie states, Latino-heavy southern-border states, and many more, have been held together through the federal devolution of power to state governments.

Figure 11.19.Devolution: Great Britain and Spain. Data sources: Esri, HERE, Garmin, NGA, USGS.

Centrifugal forces

Centrifugal forces are those that tear a country apart. These can result in separatist movements, whereby a group of people in a region push to break away and form their own nation-state. Another term commonly used in this situation is balkanization, coined in reference to the Balkan Peninsula and the breakup of the Ottoman Empire into multiple nation-states in the early twentieth century.

Size and shape have the potential to act as centrifugal forces, with large countries being more difficult to integrate with transportation and communications networks and elongated or fragmented countries having similar problems. However, evidence that these factors play a substantial role in tearing countries apart is limited. Russia, Canada, the United States, China, and other large countries have proven to be very stable, as has Chile, the most elongated of states in the world. Both the Philippines and Indonesia, highly fragmented states, do have separatist movements, but neither has succumbed to them and broken apart.

The centrifugal pull caused by population diversity is the most significant cause of balkanization and separatist movements. When states fail at unifying people into a common national identity, regionally based minority groups may call for independence. This can be along a wide range of socioeconomic and cultural lines. Language, ethnicity, and religion are common lines of division, but education and standard of living can be another. Differing views of economic policy, political philosophy, and race have led to separatism as well. Often, multiple variables work together as centrifugal forces, so it can be difficult to say, for instance, that religion alone or ethnicity alone is the proximate cause of a separatist movement.

At this point, it is useful to return to the discussion of colonial-drawn state boundaries. As discussed previously, European colonial powers often drew boundaries without regard for cultural patterns as they existed on the ground. Thus, some cohesive groups were split into different states, while others, who may have been historical rivals, were lumped together into a single state. For instance, the country of Sudan was formed under British colonialism in the late nineteenth century. It contained a majority Arab Muslim population, but much of the south consisted of non-Arabs who practiced animist and Christian religions. Upon independence in 1956, the Arab majority attempted to impose its religion and culture, including Islamic law, throughout the entire country, leading to resistance among the people of the south. Civil wars between north and south raged off and on for decades and resulted in millions of deaths until South Sudan finally gained independence in 2011 (figure 11.20).

Figure 11.20.Centrifugal forces and Balkanization Data sources: Esri, HERE, Garmin, NGA, USGS.

In Europe, the Balkans region erupted in conflict during the 1990s as the former Yugoslavia disintegrated along religious, ethnic, and linguistic lines. This conflict resulted in the deaths of over 100,000 people, the displacement of millions, and convictions of military and political leaders in the International Criminal Court for genocide. The single state of Yugoslavia, created after World War II, broke up into the nation-states of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Macedonia, Serbia, and Montenegro. Kosovo currently seeks independence from Serbia.

Active European secessionist movements are also found in Great Britain and Spain (figure 11.21). Both have devolved power to regional authorities, successfully maintaining their borders intact, yet pressures still exist. In Great Britain, Scotland, an independent nation until it was absorbed by Great Britain in the early 1700s, held an independence referendum in 2014, but a majority voted not to secede. In Spain, Catalonia, which contains the well-known city of Barcelona, has been seeking independence as well, partially on the basis of its Catalan language and partially on the basis of its higher standard of living; the people of Catalonia complain that the region sends much more tax revenue to Madrid than it receives from the central government. Spain has also faced many years of separatist activity from the Basque Country, a region with a distinct language and history. While quiet in recent years, Basque separatists have committed terrorist acts, including the murder of police officers and soldiers.

Figure 11.21.March for independence. Protesters in Barcelona supporting the secessionist movements of Scotland and Catalonia. Photo by ONiONA. Stock photo ID: 217160461. Shutterstock.com.

In much of the Middle East, the cradle of agricultural and urban civilization, territorial conflicts have shifted boundaries for millennia. In relatively recent history, the Ottoman Empire rose, drew new boundaries, then collapsed and was replaced with European colonial control and another set of boundaries. To this day, myriad groups are struggling for new nation-states tied to religious, linguistic, and ethnic identities. Most salient has been the conflict in Iraq (figure 11.22). When the strongman Saddam Hussein was removed from power by US and coalition forces in 2003, it was assumed that the country would become a stable democracy in the region. However, a long history of conflict and mistrust between different culture groups made this ideal difficult to realize. The Shiite Muslim majority, who had been severely repressed under Hussein’s rule, was happy to see him gone but then wanted to exercise its majority control. The Sunni Muslim minority population, who had enjoyed disproportionate power under Hussein, resisted Shiite attempts to take power. Then there were the Kurds, who had suffered greatly under the rule of Hussein and wanted to expand control of territory in the north of Iraq, possibly forming an independent Kurdistan with other Kurdish populations in Turkey, Syria, and Iran. Rather than achieving a peaceful democracy, these groups have fought bitter political and military battles. What was supposed to be a quick military intervention to remove a brutal dictator has transformed into civil conflict and political instability that has lasted well over a decade and resulted in over 250,000 deaths of civilians and combatants.

Border conflicts

Centrifugal forces can tear a country apart as a region attempts to break away and form a new nation-state. But there are other situations that can cause territorial instability and conflicts over borders. These can be broken down into four broad categories: identity, demarcation, resources, and security.

The case of identity relates most closely to the discussion on centrifugal forces. When a group sees itself as a nation distinct from the state it currently lives in, it can seek to break free. Sometimes its national identity straddles two or more countries, driving a movement that impacts multiple states. This is the case of the Kurds and their secessionist dreams of an independent Kurdistan, as mentioned. In other situations, a region of one state will be incorporated, voluntarily or by force, and join another state. This process is referred to as irredentism. Typically, irredentism takes place when the incorporated region is viewed as an integral part of the larger state. It can be based on historical claims to territory, as when Argentina attempted unsuccessfully to take the British-controlled Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) in 1982 or based on cultural affinity, as with Russia and the Russian-speaking population of Ukraine (figure 11.23).

Figure 11.22.Centrifugal forces in Iraq. Data sources: Vogt, Manuel et al 2015 and Wucherpfennig et al, 2011.

In the case of Ukraine, deep division lies between its western Ukrainian speaking half, which wants stronger relationships with Western Europe, and its eastern half, where Russian is the dominant language and residents prefer ties with Russia. Disagreement between the two halves rose to a point of crisis, and in 2014, Russia invaded and annexed the Crimean Peninsula. At the same time, Russia sent troops and military equipment to support pro-Russian rebels in eastern Ukraine (figure 11.24). In one especially tragic event, a commercial airliner flying over eastern Ukraine was shot down by poorly trained rebels using sophisticated Russian antiaircraft systems. Many of these pro-Russian rebels desire unification of their region with Russia.

Border disputes can also arise from disagreements and uncertainty over demarcation. Many times, natural features are used to divide states, but detailed land surveys are not always available. For instance, a border may follow the peak of a mountain range, and countries may disagree exactly where the line lies. Another problem can come from the use of rivers as borders. While rivers can serve as a natural division between two states, they are not static features. With time, rivers can change course, potentially shifting borders. This was the case between Mexico and the United States along a segment of the Rio Grande near El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. In 1864, heavy rains caused the river’s channel to shift south, adding about 700 acres to the United States. Over the years, roughly 5,000 Americans moved into this area, known as the Chamizal, and built homes and businesses. Mexico protested this loss of land, and the dispute continued until 1964, when much of the land was returned to Mexico and US residents were forced to relocate. The river is now channelized in cement and can no longer change location.

Figure 11.23.Irredentism and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Data sources: Vogt, Manuel et al. 2015 and Wucherpfennig et al, 2011.

Figure 11.24.Destroyed airport in Donetsk, eastern Ukraine. In 2014–15, pro-Russian rebels and the Ukrainian military fought for control of the airport, ultimately leaving it destroyed. Photo by Denis Kornilov. Stock photo ID: 443034715. Shutterstock.com.

Conflict over natural resources is another reason behind border disputes. The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 was partially related to oil resources and partly related to irredentism. From an irredentist standpoint, the Iraqi government had viewed Kuwait as an integral part of Iraq going back to the Ottoman Empire. But ultimately, it was a dispute over oil that led to the invasion. Iraq had major debts from its war with Iran and desperately needed oil revenue. It accused Kuwait of exceeding its OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) quota, driving down world oil prices, and of slant drilling into Iraqi oil fields along its border. Iraq therefore invaded Kuwait, taking control of the country in a matter of hours. The international community rejected Iraq’s invasion, resulting if the US-led Gulf War of 1991 that expelled Iraq from Kuwait.

Border conflicts can also occur when one state feels threatened by a neighboring state. Again, we can look at Russia’s intervention in Ukraine to illustrate the point. While one reason for Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula and support of pro-Russian rebels in Ukraine’s east was to support the Russian-speaking population, another was for security purposes. The Ukrainian government was pursuing membership in the European Union, which would draw it closer to Western interests. Ukraine had been a Republic of the Soviet Union and upon its dissolution gave Russia a long-term lease on a naval base located in Ukrainian territory. One fear of Russia was that Ukrainian ties with Europe could threaten its base, a key strategic point of naval access from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean Sea and on to the Atlantic Ocean.

An ongoing border conflict related to control of natural resources and national security is taking place in the South China Sea. Here, China is making claims to nearly the entire sea, claiming economic rights to its resources and projecting its power deep into Southeast Asia. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea states that countries have sovereign control twelve nautical miles beyond their coast and exclusive economic zones for 200 nautical miles. Within exclusive economic zones, a country has the right to fisheries, energy generation, mineral and oil extraction, or any other economic activity. China, in 1947, made claims to most of the South China Sea, delineating its claims with what is now known as the nine-dash line. Yet this line infringes on the 200-mile claims of countries such as Vietnam, Philippines, and Malaysia. To bolster its claims, China has claimed ownership of a series of islands and coral outcroppings in the sea, thus claiming all territory around them. On some of these islands, it is constructing thousands of acres of new land and building military facilities to show that it indeed has full control (figure 11.25). Conflict over these disputed maritime borders threaten stability in the region, as thousands of commercial and military ships from numerous countries ply its waters.

Terrorism

Terrorism is, unfortunately, a topic of everyday news, yet there is no agreed-upon international definition of what it is. The term implies that a group or individual uses violence in an illegitimate way for political ends. Often, but not always, it is seen as committed by non-state actors. This view contrasts with the actions of states, whose use of inappropriate violence within borders can be viewed in terms of human rights abuses and outside of borders can be considered war. Despite a lack of consensus on a definition, the United States government defines terrorism as “the unlawful use of force and violence against persons or property to intimidate or coerce a government, the civilian population, or any segment thereof, in furtherance of political or social objectives.” The key component of this definition is that an act has objectives aimed at some sort of political or social change.

Given that terrorism has political or social objectives, the reason behind it is some perceived injustice against a marginalized or oppressed group. Through terrorism, it is hoped that power or territory can be gained and the perceived injustice remedied. There are several broad categories that terrorism often falls into. With diffusion of the nation-state concept, some groups began using terrorism in struggles for national self-determination. It was used to oust European colonial powers, such as by Jewish paramilitaries against the British in Palestine. Across the Middle East and Africa, such as in Algeria, Kenya, and beyond, other nationalist groups also used guerrilla and terror tactics to strike against European colonial control. Terror has also been used by nationalist separatist movements. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) used bombings and assassinations in Great Britain from 1917 to the late 1990s, while Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA, Basque Homeland and Liberty) did the same in a struggle for Basque independence in Spain. Back in the region of Palestine, the successful creation of the Jewish state of Israel created a new terrorist movement, that of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). The PLO used bombings, hijackings, and assassinations in its struggle for the independence of Palestinians under Israeli occupation.

Figure 11.25.Chinese island building: Spratly Islands, South China Sea. Data sources: DigitalGlobe, National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, HERE, UNEP-WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, increment P Corp.

In addition to nationalist terrorist movements, other groups are based on political ideology. In these cases, the goals are broader than the creation of a nation-state. Rather, they seek to change systems that they see as unfair or exploitative. Many have been tied to international Marxism and anti-imperialism, with the goal of destroying capitalist systems and their imperial control of developing states. In Latin America, Marxist groups such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and Shining Path used bombings, murder, kidnapping, extortion, and hijacking in attempts to bring down the governments of Colombia and Peru. The 1970s and 1980s saw active Marxist terrorist groups in Europe and the United States as well, with the Italian Red Brigades and the American Weather Underground. More recently, militant environmental and animal-rights groups have been active in the United States and Europe. These groups focus primarily on destroying property rather than harming people, yet the political and social intent of their actions places them in the terrorist category. Right-wing terrorist groups, such as white-supremacists and antigovernment militias, have been active in the United States and other countries as well. One of the worst acts of terrorism in the US was committed by an antigovernment “lone wolf” who blew up the Oklahoma City Federal Building in 1995, killing 168 people, including children in an on-site day-care center.

In recent years, another motivating factor has grown in influence: religion. All major religions have fundamentalist splinter groups that commit terrorism in the name of their faith. In the United States, this has involved bombings of abortion and reproductive health clinics by right-wing fundamentalist Christian militants. Also in the United States, members of the Jewish Defense League were arrested by the FBI in 2001 prior to bombing a mosque in California. Buddhists and Hindus have assassinated and bombed Muslims in South Asia. But in recent years, the most active religiously linked terrorist groups have been Islamic (figure 11.26). The deadliest groups globally in 2016 were Islamic State, followed by Boko Haram, the Taliban, and al Qaida. Based on these groups’ regions of activity, the majority of deaths occurred in the Muslim world: Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Nigeria, and Pakistan. For instance, in 2016, seventeen of the twenty most deadly terrorist attacks took place in Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria, and Syria.

Looking specifically at the United States, both Islamists and far-right extremist groups have been the deadliest in recent decades. The largest death toll by Islamists was the September 11, 2001, attack that killed 2,996 people, while the largest far-right attack was the 1995 Oklahoma City Federal Building attack that killed 168 (figure 11.27). In addition to these outliers in terms of deaths, there were an additional thirty-eight homicide events by Islamists between 1990 and early 2017 that resulted in 136 deaths. Much less salient in the minds of many Americans is the death toll from far-right extremists. During this same time, these groups killed an additional 272 people in 178 homicide events. While Islamist extremists tended to target random victims in crowded places, more than half of the targets of far-right extremists were selected because of their religion, race or ethnicity, sexual orientation, or gender identity.

Figure 11.26.Terrorism deaths, 2007–2016. Data source: National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism

(START), 2017.

Regardless of the motivating factor driving terrorism, be it national self-determination, political ideology, or religion, there are clear geographic conditions that drive it. Most terrorist attacks occur in places with political terror and/or internal conflict. Political terror involves state-sanctioned killings, torture, disappearances, and political imprisonment by repressive governments. This was the case in Egypt and Turkey in the 2010s, when uprisings against the government resulted in political turmoil and hard-handed crackdowns on dissent. The human rights abuses that often accompany crackdowns such as these frequently result in further radicalization and easier recruitment for terrorist organizations. Likewise, high levels of terrorism are found in conflict zones, such as Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq, where myriad factions use violence against civilians and the government in their struggle for power.

Figure 11.27.September 11, 2001, terrorist attack. The South Tower of the World Trade Center collapsing. On this day, 2,996 people were killed, the largest terrorist attack in US history. Photo by Dan Howell. Stock photo ID: 83242102. Shutterstock.com.

In countries with stable political situations, such as most of Europe and North America, as well as in relatively stable places such as Tunisia in North Africa, terrorism is more likely to arise from places with a lack of opportunity, low social cohesion, and alienation. In low-income neighborhoods, lower levels of education and fewer job opportunities leave many youths in this situation. This situation can be compounded by alienation from the majority culture when communities have large immigrant populations. For instance, in the European Union, first-generation immigrant youth have much higher levels of unemployment than nonimmigrant youth and thus struggle to feel that they are full members of society.

Terrorist organizations recruit from populations that feel under attack, either from a perceived threat against their religion, an animosity against the ruling government, or alienation and lack of opportunity. People in marginalized neighborhoods and in prisons and those with criminal histories are frequently targeted for recruitment. With people in these situations, terrorism can offer a feeling of companionship and a collective group identity that makes individuals feel more secure and powerful.

From a geographic standpoint, terrorism can be seen in terms of nodes and conduits. Between each node, groups must move money, people, weapons, and information. Recruitment, training, and ultimately execution of the terrorist act must be coordinated between linked nodes. At the center of networks are the core nodes. These are often located in places with weak government control. For instance, al Qaeda has been centered in Afghanistan and northern Pakistan, while Islamic State is based in Syria. The highest levels of strategy and planning are done in these core nodes. Peripheral nodes are those that undertake the attack and are thus located close to the target area. Between the core and peripheral nodes are junction nodes that link leadership’s plans with those who will carry them out. They must recruit people for peripheral nodes, and then provide funding, training, and materiel directly to them. Both the junction and peripheral nodes are the most exposed to antiterrorism authorities, since they must work in the areas they plan to strike. From a counterterrorism perspective, the most effective strategy is to disrupt junction nodes, since they connect the core with those who will carry out attacks. If recruitment, training, and support from junction nodes is disrupted, peripheral nodes cannot succeed in carrying out attacks.

The problem with stopping so called lone wolf terrorists is that they are not tied to the typical node and conduit system. Rather, they are inspired by terrorist social media but act independently and without direct assistance from organized groups. But while it may be harder to prevent lone wolf attacks, the individuals who carry them out typically are less effective in causing damage and casualties because they work independently, without experienced trainers and sophisticated weaponry.

Go to ArcGIS Online to complete exercise 11.4: “Law of the sea: Global flash point in the South China Sea.”

Supranational organizations: Cooperation among states

To mitigate threats to stability, countries frequently cooperate in terms of trade, national security, international dispute resolution, and other areas. For these reasons, countries voluntarily form supranational organizations, agreements between three or more states that grants some decision-making powers, and thus state sovereignty, to a larger body.

The United Nations

The United Nations is a supranational organization established in 1945 for the purpose of maintaining international peace and security and solving economic and social problems facing the world community. It consists of 193 states that meet each year in the General Assembly to debate issues of global concern. A smaller Security Council works to resolve conflicts between states peacefully and can impose economic sanctions or authorize use of force against countries if negotiations fail. In addition, the Economic and Social Council coordinates work on economic, social, and environmental issues, while the International Court of Justice adjudicates legal disputes over international law. The United Nations has additional specialty programs (table 11.2) that focus on many of the issues discussed in this book.

The European Union

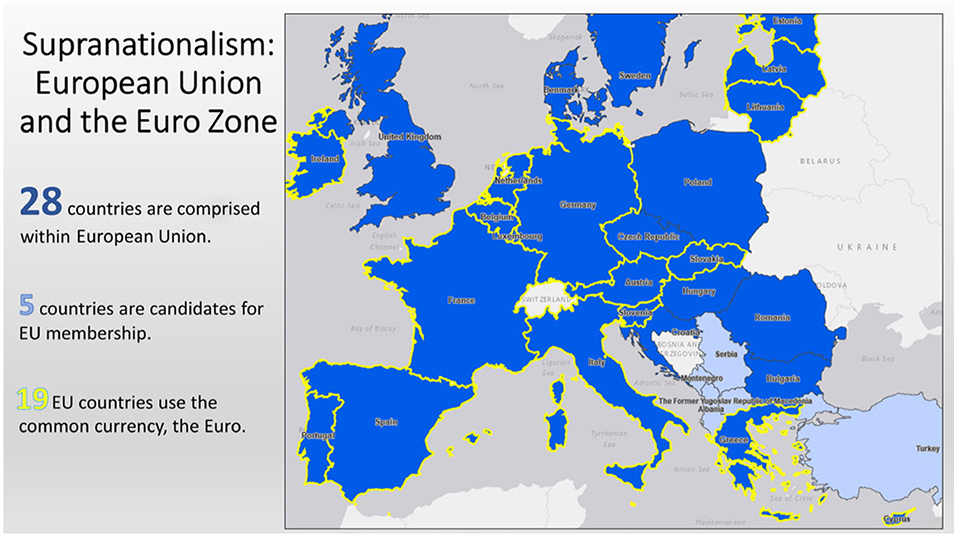

Another supranational organization that makes the news on a regular basis is the European Union. Soon after World War II, European states began a process of integration, culminating in the formation of the European Union in 1992. In 2017, there were twenty-eight member countries, but the United Kingdom was in the process of leaving the union. This union performs many functions, but the most important are that it creates a single market for goods and services, allows for free movement of EU residents, and manages a single currency (figure 11.28).

With a single market, a unified set of rules and regulations means that products made in Spain can be sold in Germany, products made in France can be sold in Poland, and so on. The same is true for services and investment. No additional regulations can limit their sale within the union, and there are no customs or border restrictions on their movement. It also means that international trade agreements are made at an EU level, not at the individual country level. With 500 million residents, it is the world’s largest single market and has trade agreements with dozens of countries outside the union. International trade increases economic growth, and the size of the EU market gives it the weight to promote a global trading system with rules that reflect EU values.

Free movement is another key function of the European Union. Residents of EU states can live and work in any other EU state. Thus, both Germany and the United Kingdom had over three million residents from other EU countries in 2016, while Spain, France, Italy, and Switzerland had well over one million. These residents work in the full spectrum of jobs, from low-skill services in hotels and restaurants to high-paying positions in banking and technology. Free movement is also enhanced by the Schengen border-free area. This agreement allows for the free movement of people between member states without being subject to border controls. Free movement applies to all people, including non-EU tourists and businesspeople. The Schengen area consists of most, but not all, EU countries as well as a few non-EU countries.