YUCATAN

BEFORE AND AFTER THE CONQUEST

BY

FRIAR DIEGO DE LANDA

SEC. I. DESCRIPTION OF YUCATAN. VARIETY OF SEASONS.

Yucatan is not an island, nor a point entering the sea, as some thought, but mainland. This error came about from the fact that the sea goes from Cape Cotoche along the Ascension passage to the Golfo Dulce on the one side, and on the other side facing Mexico, by the Desconocida before coming to Campeche, and then forming the lagoons by Puerto Real and Dos Bocas.

The land is very flat and clear of mountains, so that it is not seen from ships until they come very close; with the exception that between Campeche and Champotón there are some low ranges and a headland that is called Los Diablos.

As one comes from Veracruz toward Cape Cotoch, one finds himself at less than 20 degrees, and at the mouth of Puerto Real it is more than 23; from one point to the other it should be over a hundred and thirty leagues, direct road. The coast is low-lying, so that large ships must stay at some distance from the shore.

The coast is very full of rocks and rough points that wear the ships’ cables badly; there is however much mud, so that even if ships go ashore they lose few people.

The tides run high, especially in the Bay of Campeche, and the sea often leaves, at some places, half a league exposed; as a result there are left in the seaweed and mud and pools many small fish that serve the people for their food.

A small range crosses Yucatan from one corner to the other starting near Champotón and running to the town of Salamanca in the opposite angle. This range divides Yucatan into two parts, of which that to the south toward Lacandón and Taiza1 is uninhabited for lack of water, except when it rains. The northern part is inhabited.

This land is very hot and the sun burns fiercely, although there are fresh breezes like those from the northeast and east, which are frequent, together with an evening breeze from the sea. People live long in the country, and men of a hundred and forty years have been known.

The winter begins with St. Francis day,2 and lasts until the end of March; during this time the north winds prevail and cause severe colds and catarrh from the insufficient clothing the people wear. The end of January and February bring a short hot spell, when it does not rain except at the change of the moon. The rains come on from April until through September, during which time the crops are sown and mature despite the constant rain. There is also sown a certain kind of maize at St. Francis, which is harvested early.

SEC. II. ETYMOLOGY OF THE NAME OF THIS PROVINCE. ITS SITUATION.

This province is called in the language of the Indians Ulumil cuz yetel ceh, meaning  the land of the turkey and the deer.’ It is also called Petén, meaning

the land of the turkey and the deer.’ It is also called Petén, meaning  island,’ an error arising from the gulfs and bays we have spoken of.3

island,’ an error arising from the gulfs and bays we have spoken of.3

When Francisco Hernández de Córdoba came to this country and landed at the point he called Cape Cotoch, he met certain Indian fisherfolk whom he asked what country this was, and who answered Cotoch, which means  our houses, our homeland,’ for which reason he gave that name to the cape. When he then by signs asked them how the land was theirs, they replied Ci uthan, meaning

our houses, our homeland,’ for which reason he gave that name to the cape. When he then by signs asked them how the land was theirs, they replied Ci uthan, meaning  they say it,’ 4 and from that the Spaniards gave the name Yucatan. This was learned from one of the early conquerors, Blas Hernández, who came here with the admiral on the first occasion.

they say it,’ 4 and from that the Spaniards gave the name Yucatan. This was learned from one of the early conquerors, Blas Hernández, who came here with the admiral on the first occasion.

In the southern part of Yucatan are the rivers of Taiza (Tah-Itzá) and the mountains of Lacandón, and between the south and west lies the province of Chiapas; to pass thither one must cross four streams that descend from the mountains and unite with others to form the San Pedro y San Pablo river discovered by Grijalva in Tabasco. To the west lie Xicalango and Tabasco, one and the same province.

Between this province of Tabasco and Yucatan there are two sea mouths breaking the coast; the largest of these forms a vast lagoon, while the other is of less extent. The sea enters these mouths with such fury as to create a great lake abounding in fish of all kinds, and so full of islets that the Indians put signs on the trees to mark the way going or coming by boat from Tabasco to Yucatan. These islands with their shores and sandy beaches have so great a variety of seafowl as to be a matter of wonder and beauty; there is an infinite amount of game: deer, hare, the wild pigs of that country, and monkeys as well, which are not found in Yucatan. The number of iguanas is astonishing. On one island is a town called Tixchel.

To the north is the island of Cuba, with Havana facing at a distance of 60 leagues; somewhat further on is a small island belonging to Cuba, which they call Isla de Pinos. At the east lies Honduras, between which and Yucatan is a great arm of the sea that Grijalva called Ascension Bay; this is filled with islets on which many boats are wrecked, especially those in the trade between Yucatan and Honduras. Fifteen years ago a ship laden with many people and goods foundered, and all were drowned save one Majuelas and four others, who seized hold of a great piece of wood from the ship, and thus went three or four days without reaching any of the islets until their strength gave out and all sank except Majuelas. He came out half dead and recovered himself eating snails and shellfish; then from the islet he reached the mainland on a balsa or raft which he made as best he could out of branches. Having come to land, and while hunting for food, he came upon a crab that bit off his thumb at the first joint, and caused him intense pain. Thence he set out through difficult bush to try to reach Salamanca, and when night came he climbed a tree from which he saw a great tiger waylay and kill a deer; then when morning came he ate what the tiger had left.

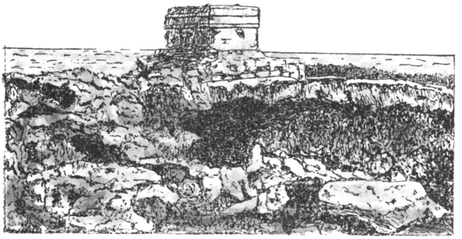

In front of Yucatan, somewhat below Cape Cotoch, lies Cuzmil (Cozumel), across a 5 -league channel where the sea runs with a strong current between the mainland and the island. Cozumel is an island fifteen leagues long by five wide. The Indians are few in number, and of the same language and customs as those of Yucatan. It lies at the 20th degree of latitude. Thirteen leagues below Point Cotoch is the Isla de las Mugeres, 2 leagues off the coast opposite Ekab.

Photo by Maler

ISLA DE LAS MUGERES

SEC. III. CAPTIVITY OF GERONIMO DE AGUILAR. EXPEDITION OF HERNANDEZ DE CORDOBA AND GRIJALVA TO YUCATAN.

It is said that the first Spaniards to come to Yucatan were Gerónimo de Aguilar, a native of Ecija, and his companions. These, in 1511, upon the break-up at Darien resulting from the dissensions between Diego de Nicueza and Vasco Núñez de Balboa, followed Valdivia on his voyage in a caravel to San Domingo, to give account to the admiral and the governor, and to bring 20,000 ducats of the king’s. On the way to Jamaica the caravel grounded on the shoals known as the Viboras, where it was lost with all but twenty men. These went with Valdivia in a boat without sails, and only some poor oars and no provisions, and were at sea for thirteen days. After nearly half of them had died of hunger, the rest reached the coast of Yucatan at a province called that of the Maya, whence the language of Yucatan is known as Mayat‘an, meaning the  Maya speech.’

Maya speech.’

These poor fellows fell into the hands of a bad cacique, who sacrificed Valdivia and four others to their idols, and served them in a feast to the people. Aguilar and Guerrero and five or six others he saved to fatten. These broke their prison and came to another chief who was an enemy of the first, and more merciful; he made them his slaves, and his successor treated them with much kindness. However, all died of grief, save only Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero. Of these Aguilar was a good Christian and had a breviary, by which he kept count of the feast days and finally escaped on the arrival of the Marquis Hernando Cortés, in 1519.

Guerrero learned the language and went to Chectemal (Chetumal), which is Salamanca de Yucatan. Here he was received by a chief named Nachan Can, who placed in his charge his military affairs; in these he did well and conquered his master’s enemies many times. He taught the Indians to fight, showing them how to make barricades and bastions. In this way, and by living as an Indian, he gained a great reputation and married a woman of high quality, by whom he had children, and he made no attempt to escape with Aguilar. He decorated his body, let his hair grow, pierced his ears to wear rings like the Indians, and is believed to have become an idolater like them.

During Lent of 1517 Francisco Hernández de Córdoba sailed from Cuba with three ships to procure slaves for the mines, as the population of Cuba. was diminishing.5 Others say he sailed to discover new lands. Taking Alaminos as a pilot he landed on Isla de las Mugeres, to which he gave this name because of the idols he found there, of the goddesses of the country, Aixchel, Ixchebeliax, Ixhunié, Ixhunieta, vestured from the girdle down, and having the breasts covered after the manner of the Indians. The building was of stone, such as to astonish them; and they found certain objects of gold, which they took. Arriving at Cape Cotoch they directed their course to the Bay of Campeche, where they disembarked on Lazarus Sunday, whence they called the place Lazaro. They were well received by the chief and the Indians marveled at seeing the Spaniards, touching their beards and persons.

At Campeche they found a building in the sea near to the land, all square and in steps, on the top of which was an idol with two fierce animals devouring his flanks; also a great thick serpent swallowing a lion; the animals were covered with the blood of sacrifices. At Campeche they learned of a large town nearby, which was Champotón; landing there they found a chief named Moch-Covoh, a warlike man who called his people together against the Spaniards. Francisco Hernández was much disturbed seeing in this what must happen; but not to show a less spirit he put his men in order and had the artillery fired from the ships. The Indians however, notwithstanding the strange sound, smoke and fire of the guns, attacked with great cries; the Spaniards resisted, inflicting severe wounds and killing many. Nevertheless the chief so inspired his people that they forced the Spaniards to retire, killing twenty, wounding fifty, and taking alive two whom they afterwards sacrificed. Francisco Hernández came off with thirty-three wounds, and thus returned downcast to Cuba, where he reported that the land was good and rich, because of the gold he found on the Isla die las Mugeres.

These stories moved Diego Velásquez, governor of Cuba, as well as many others, so that he sent his nephew Juan de Grijalva with four ships and 200 men. With him went Francisco de Montejo, to whom one ship belonged, the expedition sailing on the 1st of May, 1518.

They took with them the same Alaminos as pilot, and landed on the island of Cozumel, from which the pilot descried the coast of Yucatan which with Francisco Hernández he had previously coasted along, on the right hand going south. Desiring to see whether it was an island, they turned left and followed by the bay they called Ascension, because of entering it on that day. Then turning back they followed the whole coast until they reached Champotón for the second time; landing here for water, one man was killed and fifty wounded, among them Grijalva, who received two arrows and lost a tooth and a half. In this maner they departed and named the harbor the Puerto de Mala Pelea. On this voyage they discovered New Spain, Pánuco and Tabasco, where they stayed for Five months, and also tried to make a landing at Champotón. This the Indians resisted with such spirit as to come out close to the ships in their canoes, in order to shoot their arrows. So they made sail and departed.

When Grijalva returned from his voyage of discovery and trade in Tabasco and Ulúa, the great captain Hernando Cortés was in Cuba; and he on the news of such a country and such riches, conceived the desire of seeing it, and even of acquiring it for God, for his king, for himself, and for his friends.

SEC. IV. EXPEDITION OF CORTES TO COZUMEL. LETTER TO AGUILAR AND HIS FRIENDS.

Hernando Cortés sailed from Cuba with eleven ships, the largest being of 100 tons burden, placing in them eleven captains, and himself being one of these. He took along 500 men, some horses, and goods for barter, having Francisco de Montejo as a captain and Alaminos as chief pilot of the armada. On the admiral’s ship he set a banner of white and blue in honor of Our Lady, whose image, together with the cross, he always placed wherever he destroyed idols. On the banner was a red cross surrounded by a legend reading: Amici sequamur crucem, et si habuerimus fidem, in hoc signo vinceinus.

With this fleet and no further equipment he set sail and arrived at Cozumel with ten ships, one becoming separated in a storm; he however recovered it later on the coast. They arrived at Cozumel on the north, where they found fine buildings of stone for the idols, and a fine town; but the inhabitants seeing so great a fleet and the soldiers disembarking, all fled to the woods.

On reaching the town the Spaniards sacked it and lodged themselves. Seeking through the woods for the natives they came on the chief’s wife and children. Through an Indian interpreter named Melchior, who had been with Francisco Hernández and Grijalva, they learned it was the chief’s wife, to whom and the children Cortés gave presents and caused them to send for the chief. Him on his arrival he treated very well, gave him some small grifts and returned to him his wife and children, with all the things that had been taken in the town; and begged him to have the Indians return to their houses, saying that when they came everything that had been taken away from them would be restored. When they were thus restored, he preached to them the vanity of idols, and persuaded them to adore the cross; this he placed in their temples with an image of Our Lady, and therewith public idolatry ceased.

Here Cortés learned that there were bearded men six days away, in the power of a chief, and persuaded the Indians to send a messenger to summon them. With difficulty he found one that would go, because of the fear they had of the chief of the bearded men. He then wrote this letter: :

Noble sirs: I left Cuba with a fleet of eleven ships and 500 Spaniards, and laid up at Cozumel, whence I write this letter. Those of the island have assured me that there are in the country five or six men with beards and resembling us in all things. They are unable to give or tell me other indications, but from these I conjecture and hold certain that you are Spaniards. I and these gentlemen who go with me to settle and discover these lands urge that within six days from receiving this you come to us, without making further delay or excuse. If you shall come we will make due acknowledgment, and reward the good offices which this armada shall receive from you. I send a brigantine that you may come in it, and two boats for safety.

The Indians took this letter wrapped in their hair, and gave it to Aguilar. But the Indians delaying beyond the time appointed, those on the ships believed them killed, and returned to the port of Cozumel. Cortés then seeing that neither the Indians nor the bearded men returned, set sail the next day. On that day, however, a ship sprung a leak and it was necessary to return to port. While the repairs were being made Aguilar, having received the letter, crossed the channel between Yucatan and Cozumel in a canoe; when those of the fleet seeing him approach went to see who it was, Aguilar asked whether they were Christians. When they answered Yes, and Spaniards, he wept for joy and falling on his knees gave thanks to God. He then asked the Spaniards if it was Wednesday.

The Spaniards took him all naked as he was to Cortés, who clothed him and treated him with much affection; and Aguilar related there 6 his peril and labors, and the death of his companions, and how it was impossible to send word to Guerrero in so short a time, he being more than eighty leagues away.

Aguilar having told his story, and being an excellent interpreter, Cortés renewed the preaching of the adoration of the cross, and put the idols out of the temples; and they say that this preaching by Cortés made such an impression on those of Cuzco 7 that they came out to the shore saying to the Spaniards who passed:  Maria, Maria, Cortés, Cortés.”

Maria, Maria, Cortés, Cortés.”

Cortés departed thence, touched Campeche in passing, but did not make a stop until he reached Tabasco. Here among other presents and Indian women which those of Tabasco gave to him was one who was afterwards called Marina. She was from Xalisco, a daughter of noble parents, stolen when small and sold in Tabasco, and later sold in Xicalango and Champotón, where she learned the language of Yucatan. By this she was able to understand Aguilar, and thus God provided Cortés with good and faithful interpreters, through whom he acquired knowledge and intimacy with Mexican matters. With these Marina was well posted, having mingled with Indian merchants and leading people, who spoke of them daily.

SEC. V. PROVINCES OF YUCATAN. ITS PRINCIPAL ANCIENT STRUCTURES,

Some old men of Yucatan say that they have heard from their ancestors that this country was peopled by a certain race who came from the East, whom God delivered by opening for them twelve roads through the sea. If this is true, all the inhabitants of the Indies must be of Jewish descent because, the straits of Magellan having been passed, they must have spread over more than 2000 leagues of territory now governed by Spain.

The language of this country is all one, a fact which aided greatly in its conversion, although along the coasts there are differences in words and accents. Those living on the coast are thus more polished in their behavior and language; and the women cover their breasts, which those further inland do not.

The country is divided into provinces subject to the nearest Spanish settlement. The province of Chectemal and Bak-halal is subject to Salamanca,. The provinces of Ekab, of Cochuah and of Cupul are subject to Valladolid. Those of Ahkin-Chel and of Izamal, of Sututa, of Hocabaihumun, of Tutuxiu, of Cehpech, and of Chakan, are attached to the city of Mérida; Camol (Canul), Campech, Champutun and Tixchel are assigned to San Francisco de Campeche.

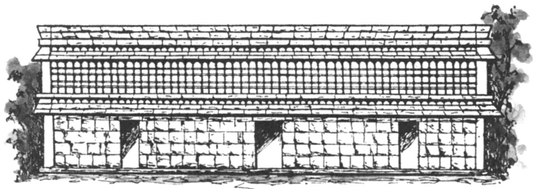

There are in Yucatan many edifices of great beauty, this being the most outstanding of all things discovered in the Indies; they are all built of stone finely ornamented, though there is no metal found in the country for this cutting. These buildings are very close to each other and are temples, the reason for there being so many lying in the frequent changes of the population, and the fact that in each town they erected a temple, out of the abundance of stone and lime, and of a certain white earth excellent for buildings.

These edifices are not the work of other peoples, but of the Indians them-selves, as appears by stone figures of men, unclothed but with the middle covered by certain long fillets which in their language are called ex, together with other devices worn by the Indians.

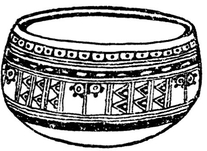

While the author of this work was in that country, there was found in a building that had been demolished a large urn with three handles, painted on the outside with silvered colors, and containing the ashes of a cremated body, together with some pieces of the arms and legs, of an unbelievable size, and with three fine beads or counters of the kind the Indians use for money. At Izamal there were eleven or twelve of these buildings in all, with no memory of their builders; on the site of one of these, at the instance of the Indians, there was established the monastery of San Antonio, in the year 1550.

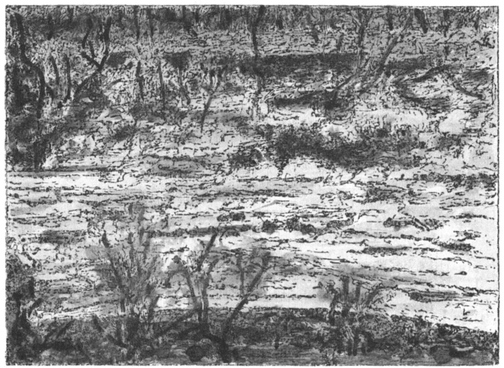

Photo by George Onkicy Totten

THE CENOTE OF SACRIFICE AT CHICHEN JTZA

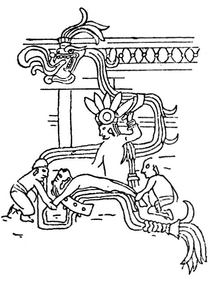

The next most important edifices are those of Tikoch and of Chichén Itzá, which will be described later. Chichén Itzá is finely situated ten leagues from Izamal and eleven from Valladolid, and they tell that it was ruled by three lords, brothers that came to the country from the West. These were very devout, built very handsome temples, and lived unmarried and most honorably. One of them either died or went away, whereupon the others conducted themselves unjustly and wantonly, for which they were put to death. Later on we shall describe the decorations of the main edifice, also telling of the well into which they cast men alive as a sacrifice; and also other precious objects. It is over seven stages down to the water, over a hundred feet across and marvelously cut in the living rock. The water appears green, which they say is caused by the trees that surround it.

SEC. VI. CUCULCAN. FOUNDATION OF MAYAPAN.

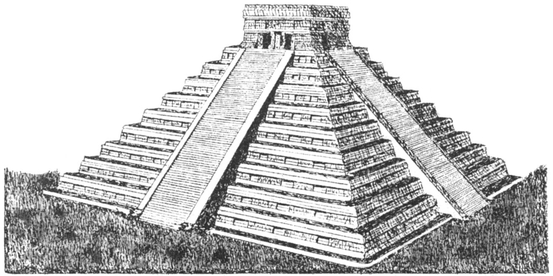

The opinion of the Indians is that with the Itzás who settled Chichén Itzá there ruled a great lord named Cuculcán, as an evidence of which the principal building is called Cuculcán.

THE PYRAMID OF KUKULCAN

As restored by the Mexican Government, under the direction of Don Eduardo Martinez

They say that he came from the West, but are not agreed as to whether he came before or after the Itzás, or with them. They say that he was well disposed, that he had no wife or children, and that after his return he was regarded in Mexico as one of their gods, and called Cezalcohuati [Quetzalcóatl]. In Yucatan also he was reverenced as a god, because of his great services to the state, as appeared in the order which he established in Yucatan after the death of the chiefs, to settle the discord caused in the land by their deaths.

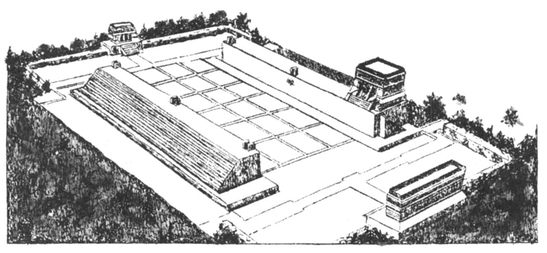

MAYAPAN

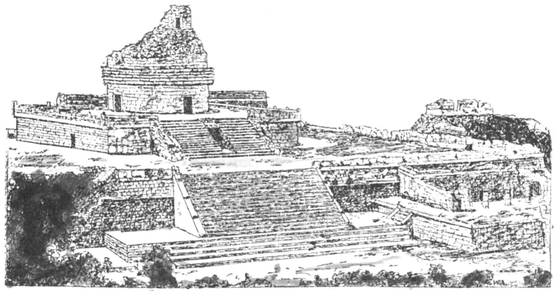

This Cuculcán, having entered into an agreement with the native lords of the country, undertook the founding of another city wherein he and they might live, and to which all matters and business should be brought. To this end he chose a fine site eight leagues further inland from where Mérida now lies, and some fifteen or sixteen from the sea. They surrounded the place with a very broad wall of dry stone some eighth of a league in extent, leaving only two narrow doorways; the wall itself was low. In the middle of the enclosure they built their temples, calling the largest Cuculcán, the same as at Chichén Itzá. They built another circular temple, different from all others in the country, and with four entrances; also many others about them, connected one with the other. Within the enclosure they built houses for the lords alone, among whom the country was divided, assigning villages to each according to the antiquity of their lineage and their personal qualifications. Cuculcán did not call the city after himself, as was done by the Ah-Itzaes at Chichén Itzá (which means the  Well of the Ah-Itzaes ’ ) , but called it Mayapán, meaning the

Well of the Ah-Itzaes ’ ) , but called it Mayapán, meaning the  Standard of the Mayas,’ the language of the country being known as Maya. The Indians of today call it Ich-pa, meaning ‘Within the Fortifications.’

Standard of the Mayas,’ the language of the country being known as Maya. The Indians of today call it Ich-pa, meaning ‘Within the Fortifications.’

After Catherwood

ROUND TOWER AT MAYAPAN

Cuculcán lived for some years in this city with the chiefs, and then leaving them in full peace and amity returned by the same road to Mexico. On the way he stopped at Champotón, and there in memorial of himself and his departure he erected in the sea, at a good stone’s throw from the shore, a fine edifice similar to those at Chichén Itzá. Thus did Cuculcán leave a perpetual memory in Yucatan.

CARACOL AT CHICHEN ITZA

As uncovered under the care of the Carnegie Institution of Washington

SEC. VII. GOVERNMENT, PRIESTHOOD, SCIENCES, LETTERS AND BOOKS IN YUCATAN.

On the departure of Cuculcán the chiefs agreed that for the permanence of the state the house of the Cocoms should exercise the chief authority, it being the oldest and richest, or perhaps because its head was at that time a man of greater power. This done, they ordained that within the enclosure there should only be temples and residences of the chiefs, and of the High Priest; that they should build outside the walls dwellings where each of them might keep some serving people, and whither the people from the villages might come whenever they had business at the city. In these houses each one placed his mayordomo, who bore as his sign of authority a short thick baton, and who was called the Caluac. This officer held supervision over the villages and those in charge of them, to whom he sent advices as to the things needed in the chief’s establishment, as birds, maize, honey, salt, fish, game, clothing and other things. The Caluac always attended in the chief’s house, seeing what was needed and providing it promptly, his house standing as the office of his chief.

It was the custom to hunt out the crippled and the blind in the villages, and give them their necessities. The chiefs appointed the governors and, if worthy, confirmed their offices to their sons. They enjoined upon them good treatment of the common people, the peace of the community, and that all should be diligent in their own support and that of the lords.

Upon all the lords rested the duty of honoring, visiting and entertaining Cocom, accompanying and making festivals for him, and of repairing to him in difficult affairs. They lived in peace with each other, and with much diversion according to their custom, in the way of dances, feasts and hunting.

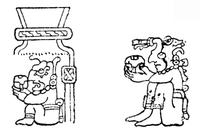

The people of Yucatan were as attentive to matters of religion as of government, and had a High Priest whom they called Ahkin May, or also Ahaucan May, meaning the Priest May, or the High Priest May. He was held in great reverence by the chiefs, and had no allotment of Indians for himself, the chiefs making presents to him in addition to the offerings, and all the local priests sending him contributions. He was succeeded in office by his sons or nearest kin. In him lay the key to their sciences, to which they most devoted themselves, giving counsel to the chiefs and answering their inquiries. With the matter of sacrifices he rarely took part, except on great festivals or business of much moment. He and his disciples appointed the priests for the towns, examining them in their sciences and ceremonies; put in their charge the affairs of their office, and the setting of a good example to the people; he provided their books and sent them forth. They in turn attended to the service of the temples, teaching their sciences and writing books upon them.

They taught the sons of the other priests, and the second sons of the chiefs, who were brought to them very young for this purpose, if they found them inclined toward this office.

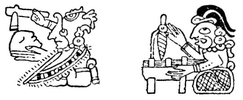

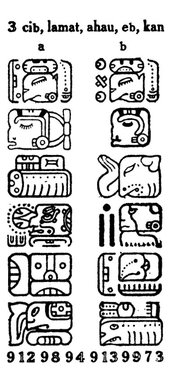

The sciences which they taught were the reckoning of the years, months and days, the festivals and ceremonies, the administration of their sacraments, the omens of the days, their methods of divination and prophecies, events, remedies for sicknesses, antiquities, and the art of reading and writing by their letters and the characters wherewith they wrote, and by pictures that illustrated the writings.

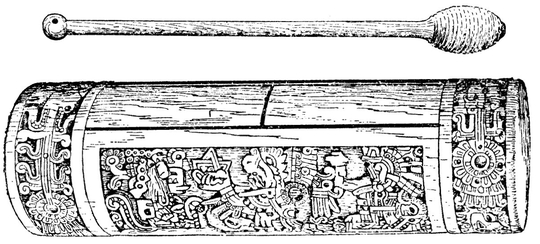

They wrote their books on a long sheet doubled in folds, which was then enclosed between two boards finely ornamented; the writing was on one side and the other, according to the folds. The paper they made from the roots of a tree, and gave it a white finish excellent for writing upon. Some of the principal lords were learned in these sciences, from interest, and for the greater esteem they enjoyed thereby; yet they did not make use of them in public.

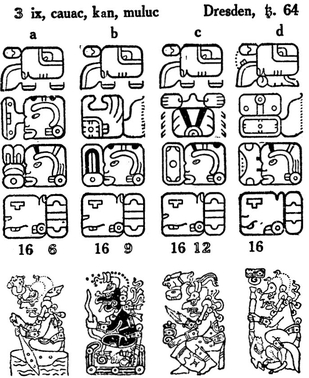

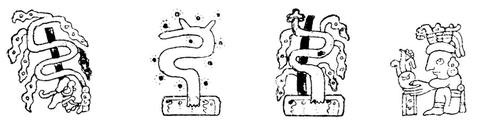

* The text figure shows the general arrangement of the texts in both the Dresden and Madrid codices; that in the Paris codex and on the monuments was quite different.

Here, in section, or tzolkin 64 of the Dresden, we see the figure of Itzamná in four different activities, in each accompanied by one of the four major food animals, the turkey, iguana, fish and deer. Above each are four glyphs, the first identical save for the subfix clement in the fourth column; this may be taken as an introductory to an invocation, or chanting rhythm, such as actually found in one of our most important Maya manuscripts, the Ritual of the Bacabs. The four glyphs across in the second line represent the North, West, South and East. In the next position we see the head as of a ‘lord,’ wearing a ceremonial banded headdress, preceded by the known signs for the four colors attached to the four Directions: White, Black, Yellow, Red. In the bottom row the repeated glyph of ltzamná, accepted as such from its constant occurrence above his figure as shown here.

Finally, since the composition of the original codex of which the existing  Dresden codex ’ is rather clearly a copy, is to be placed from its own internal evidence as relating to the moon and eclipse calculation finally worked out probably at Copan, about the year 750 A. D., the uncertainties involved in any effort to read this in the modern forms of Yucatecan Maya (or other), are just about as great as should one ignorant of historical English try to treat the text of Beowulf as if it showed the spoken English of today.

Dresden codex ’ is rather clearly a copy, is to be placed from its own internal evidence as relating to the moon and eclipse calculation finally worked out probably at Copan, about the year 750 A. D., the uncertainties involved in any effort to read this in the modern forms of Yucatecan Maya (or other), are just about as great as should one ignorant of historical English try to treat the text of Beowulf as if it showed the spoken English of today.

SEC. XIII. ARRIVAL OF THE TUTUL-XIUS AND THE ALLIANCE THEY MADE WITH THE LORDS OF MAYAPAN. TYRANNY OF COCOM, THE RUIN OF HIS POWER AND OF THE CITY OF MAYAPAN.

The Indians relate that there came into Yucatan from the south many tribes with their chiefs, and it seems they came from Chiapas, although this the Indians do not know; but the author so conjectures from the many words and verbal constructions that are the same in Chiapas and in Yucatan, and from the extensive indications of sites that have been abandoned. They say that these tribes wandered forty years through the wilderness of Yucatan, having in that time no water except from the rains; that at the end of that time they reached the Sierra that lies about opposite the city of Mayapán, ten leagues distant. Here they began to settle and erect many fine edifices in many places; that the inhabitants of Mayapán held most friendly relations with them, and were pleased that they worked the land as if they were native to it. In this manner the people of the Tutul-xius subjected themselves to the laws of Mayapán, they intermarried, and thus the lord Xiu of the Tutul-xius came to find himself held in great esteem by all.8

Photo by Maler

EIGHTH CENTURY STONE RESIDENCE IN THE SIERRA DIS ICT

ICT

These tribes lived in such peace that they had no conflicts and used neither arms nor bows, even for the hunt, although now today they are excellent archers. They only used snares and traps, with which they took much game. They also had a certain art of throwing darts by the aid of a stick as thick as three fingers, hollowed out for a third of the way, and six palms long; with this and cords they threw with force and accuracy.9

They had laws against delinquents which they executed rigorously; such as against an adulterer, whom they turned over to the injured party that he might either put him to death by throwing a great stone down upon his head, or he might forgive him if he chose. For the adulteress there was no penalty save the infamy, which was a very serious thing with them. One who ravished a maiden was stoned to death, and they relate a case of a chief of the Tutul-xiu who, having a brother accused of this crime, had him stoned and afterwards covered with a great heap of rocks. They also say that before the foundation of the city they had another law providing the punishment of adulterers by drawing out the intestines through the navel.

The governing Cocom began to covet riches, and to that end negotiated with the garrison kept by the kings of Mexico in Tabasco and Xicalango, that he would put the city in their charge. In this way he introduced the Mexicans into Mayapán, oppressed the poor, and made slaves of many. The chiefs would have slain him but for fear of the Mexicans. The lord of the Tutul-xiu never gave his consent to this. Then those of Yucatan, seeing themselves so fixed, learned from the Mexicans the art of arms, and thus became masters of the bow and arrow, of the lance, the axe, the buckler, and strong cuirasses made of quilted cotton, 10 together with other implements of war. Soon they no longer stood in awe of nor feared the Mexicans, but rather held them of slight moment. In this situation several years passed.

This Cocom was the first who made slaves; but out of this evil came the use of arms to defend themselves, that they might not all become slaves. Among the successors of the Cocom dynasty was another one, very haughty and an imitator of Cocom, who made another alliance with the Tabascans, placing more Mexicans within the city, and began to act the tyrant and to enslave the common people. The chiefs then attached themselves to the party of Tutul-xiu, a man patriotic like his ancestors, and they plotted to kill Cocom. This they did, killing at the same time all of his sons save one who was absent; they sacked his dwelling and possessed themselves of all his property, his stores of cacao and other fruits, saying that thus they repaid themselves what had been stolen from them. The struggles between the Cocoms, who claimed that they had been unjustly expelled, and the Xius, went on to such an extent that after having been established in this city for more than five hundred years, they abandoned and left it desolate, each going to his own country.

SEC. IX. CHRONOLOGICAL MONUMENTS OF YUCATAN. FOUNDATION OF THE KINGDOM OF SOTUTA. ORIGIN OF THE CHELS. THE THREE PRINCIPAL KINGDOMS OF YUCATAN.

According to the reckoning of the Indians it has been 120 years since the abandonment of Mayapán. On the site of that city are to be found seven or eight stones each ten feet in height, round on one side, well carved and bearing several lines of the characters they use, so worn away by the water as to be unreadable, although they are thought to be a monument of the foundation and destruction of the city. There are others like them at Zilán, a town on the coast, except that they are taller.11 The natives being asked what they were, answered that it was the custom to set up one of these stones every twenty years, that being the number by which they reckon their periods. This however seems to be without warrant, for in that event there must have been many others; besides that there are none of them in any other places than Mayapán and Zilán.

The most important thing that the chiefs who stripped Mayapán took away to their own countries were the books of their sciences, for they were always very subject to the counsels of their priests, for which reason there are so many temples in those provinces.

That son of Cocom who had escaped death through being away on a trading expedition to the Ulúa country, which is beyond the city of Salamanca, on hearing of his father’s death and the destruction of the city, returned in haste and gathered his relatives and vassals; they settled in a site which he called Tibulon, meaning ‘we have been played with.’ 12 They built many other towns in those forests, and many families have sprung from these Cocoms. The province where this chief ruled was called Sututa.

The lords of Mayapán took no vengeance on those Mexicans who gave aid to Cocom, seeing that they had been influenced by the governor of the country, and since they were strangers. They therefore left them undisturbed, granting them leave to settle in a place apart, or else to leave the country; in staying, however, they were not to intermarry with the natives, but only among themselves. These decided to remain in Yucatan and not return to the lagoons and mosquitos of Tabasco, and so settled in the province of Canul, which was assigned them, and where they remained until the second Spanish wars.

They say that among the twelve priests of Mayapán was one of great wisdom who had an only daughter, whom he had married to a young nobleman named Ah-Chel. This one had sons who were called the same as their father, according to the custom of the country. They say that this priest predicted the fall of the city to his son-in-law; they tell that on the broad part of his arm the old priest inscribed certain characters of great import in their estimation. With this distinction conferred on him he went to the coast and established a settlement at Tikoch, a great number of people following him. Thus arose the renowned families of the Chels, who peopled the most famous province of Yucatan, which they named after themselves the province of Ahkin-Chel. Here was Izamal, where the Chels resided; and they multiplied in Yucatan until the coming of the admiral Montejo.

Between these great princely houses of the Cocoms, Xius and Chels there was a constant feud and enmity, which still continues even though they have become Christians. The Cocoms call the Xius strangers and traitors, murdering their natural lord and plundering his possessions. The Xius say they are as good as the others, as ancient and as noble; that they were not traitors but liberators, having slain a tyrant. The Chel said that he was as good as the others in lineage, being the descendant of the most renowned priest in Mayapán; that as to himself he was greater than they, because he had known how to make himself as much a lord as they were. The quarrel extended even to their food supply, for the Chel, living on the coast, would not give fish or salt to the Cocom, making him go a long distance for it; and the Cocom would not permit the Chel to take any game or fruits.

SEC. X. VARIOUS CALAMITIES FELT IN YUCATAN IN THE PERIOD BEFORE THE CONQUEST BY THE SPANIARDS: HURRICANE, WARS, ETC.

These tribes enjoyed more than twenty years of abundance and health, and they multiplied so that the whole country seemed like a town. At that time they erected temples in great number, as is today seen everywhere; in going through the forests there can be seen in the groves the sites of houses and buildings marvelously worked.

Succeeding this prosperity, there came on one winter night at about six in the evening a storm that grew into a hurricane of the four winds. The storm blew down all the high trees, causing great slaughter of all kinds of game; it overthrew the high houses, which being thatched and having fires within for the cold, took fire and burned great numbers of the people, while those who escaped were crushed by the timbers.

The hurricane lasted until the next day at noon, and they found that those who lived in small houses had escaped, as well as the newly married couples, whose custom it was to live for a few years in cabins in front of their fathers or fathers-in-law. The land thus then lost the name it had borne, that  of the turkeys and the deer,” and was left so treeless that those of today look as if planted together and thus all grown of one size. To look at the country from heights it looks as if all trimmed with a pair of shears.

of the turkeys and the deer,” and was left so treeless that those of today look as if planted together and thus all grown of one size. To look at the country from heights it looks as if all trimmed with a pair of shears.

Those who escaped aroused themselves to building and cultivating the land, and multiplied greatly during fifteen years of health and abundance, the last year being the most fertile of all. Then as they were about to begin gathering the crops there came an epidemic of pestilencial fevers that lasted for twenty-four hours; then on its abating the bodies of those attacked swelled and broke out full of maggoty sores, so that from this pestilence many people died and most of the crops remained ungathered.

After the passing of the pestilence they had sixteen other good years, wherein they renewed their passions and feuds to the end that 150,000 men were killed in battle. With this slaughter they ceased and made peace, and rested for twenty years. After that there came again a pestilence, with great pustules that rotted the body, fetid in odor, and so that the members fell in pieces within four or five days.

Since this last plague more than fifty years have now passed, the mortality of the wars was twenty years prior, the pestilence of the swelling was sixteen years before the wars, and twenty-two or twenty-three after the destruction of the city of Mayapán. Thus, according to this count, it has been 125 years since its overthrow, within which the people of this country have passed through the calamities described, besides many others after the Spaniards began to enter, both by wars and other afflictions sent by God; so that it is a marvel there is any of the population left, small as it is.

SEC. XI. PROPHECIES OF THE COMING OF THE SPANIARDS. HISTORY OF FRANCISCO DE MONTEJO, FIRST ADMIRAL OF YUCATAN.

As the Mexican people had signs and prophecies of the coming of the Spaniards and the end of their power and religion, so also did those of Yucatan some years before they were conquered by Admiral Montejo. In the district of Mani, in the province of Tutul-xiu, an Indian named Ah-cambal, filling the office of Chilán,13 that is one who has charge of giving out the responses of the demon, told publicly that they would soon be ruled by a foreign race who would preach a God and the virtue of a wood which in their tongue he called vahom-ché, meaning a tree lifted up, of great power against the demons.

The successor of the Cocoms, called Don Juan Cocom after he became a Christian, was a man of great reputation and very learned in matters and affairs of the country, very wise and well informed. He was on familiar terms with the author of this book, Fray Diego de Landa, recounting to him many ancient things, and showing him a book which had belonged to his grandfather, the son of the Cocom whom they killed in Mayapán. In this was painted a deer, and his grandfather had told him that when there should come into the land large deer (for so they called the cows), the worship of the gods would cease; and this had been fulfilled, because the Spaniards brought along large cows.

The admiral Francisco de Montejo was a native of Salamanca, and came to the Indies after the settling of the city of San Domingo, in the Island of Española, after having lived for a time in Sevilla, where he left an infant son whom he had there. He came to the island of Cuba, where he gained a livelihood and made many friends by his fine qualities, among these being Diego Velásquez the governor of the island, and Hernando Cortés. The governor having determined to send his nephew Juan de Grijalva to redeem the territory of Yucatan and to discover new lands, after the news brought by Francisco Hernández de Córdova of how rich the land was, he decided to have Montejo go with Grijalva. He being wealthy supplied one of the ships and much provisioning, and was thus one of the second party of Spaniards that discovered Yucatan; having seen the coast of Yucatan he resolved to enrich himself there instead of in Cuba.

Learning the determination of Hernando Cortés, he followed him with his person and fortune, Cortés giving him command of a ship and making him its captain. In Yucatan they then met Gerónimo de Aguilar, from whom Montejo acquired knowledge of the language of the country and its matters. Cortés having landed in New Spain began at once to make settlements, calling the first town Vera Cruz, after the blazon of his banner. Montejo was appointed as one of the royal alcaldes of the town, acquitting himself discreetly, and being so publicly named by Cortés when he returned from the trip he made around the coast. For this he was sent to Spain as one of the Procurators of the state of New Spain, that he might convey to the King his fifths, together with a relation of the countries discovered, and the things about taking place there.

When Francisco de Montejo arrived at the Court of Castile, Juan Rodriguez de Fonseca, Bishop of Burgos, was president of the Council of the Indies, and he was wrongly informed to Cortés’ prejudice, by Diego Velásquez, the governor of Cuba, who claimed likewise the governorship of New Spain. The majority of the Council thinking that Cortés seemed to be asking money of the King instead of sending it, and Montejo finding that on account of the absence of the Emperor in Flanders the affair went ill, he persevered for seven years from the time he left the Indies (which was in 1519), until he re-embarked in 1526. By his perseverance he challenged the president and Pope Adrian who was regent for the kingdom, and talked with the Emperor to the effect that he gave his approval and disposed of the affairs of Cortés as justice required.

SEC. XII. MONTEJO. SAILS FOR YUCATAN AND TAKES POSSESSION OF THE COUNTRY. THE CHELS CEDE TO HIM THE SITE OF CHICHEN ITZA. THE INDIANS FORCE HIM TO LEAVE.

During the time that Montejo was at Court he got for himself the conquest of Yucatan, although he might have had other things, and received the title of Admiral. He then went to Sevilla, and took with him a nephew thirteen years of age, bearing his own name. He also found his son, twenty-eight years of age, and took him along. He arranged a marriage with a rich widow of Sevilla, and was thus able to gather 500 men whom he embarked in three ships; setting sail he made port at Cozumel, an island of Yucatan. The Indians there did not oppose him, having been made friendly by the Spaniards under Cortés. There he learned many words of their language, and how to make himself understood by them, after which he sailed to Yucatan. Here he took possession, one of his Ensigns saying, banner in hand:  In the name of God I take possession of this land for God and the King of Castile.”

In the name of God I take possession of this land for God and the King of Castile.”

In this way he sailed down the coast, which was then well populated, until he landed at Conil, a town of the coast; the Indians were alarmed at seeing so many horses and men, and sent word to all the country of what was happening, watching the purpose of the Spaniards.

The Indians of the province of Chicaca [Chuaca] came to visit the admiral in peace and were well received; among them came a man of great strength who, taking a cutlass from a young negro who bore it, tried to kill the admiral with it. The latter defended himself and the Spaniards came up and stopped the trouble; but they learned that it was necessary to proceed on their guard.

The admiral sought to learn what was the largest city and found it to be Tikoh [Tikoch], a city of the Chels, situated on the coast further down along the course the Spaniards were taking. The Indians thinking they were on their way to leave the country, were not aroused, nor did they oppose their march. In this way they came to Tikoch, and found it a much larger and finer city than they had supposed. It was fortunate that the chiefs of that country were not the Covohes of Champotón, who were always braver than the Chels. The latter with their priesthood, which still exists today, were not as haughty as the others, and hence allowed the admiral to make a settlement for his people, giving him the site of Chichén Itzá for the purpose, an excellent place seven leagues away. From this position he set out to the conquest of the country, a task rendered easy by the non-resistance of the people of Ahkin-Chel, and the assistance of those of Tutul-xiu, by reason whereof the others offered little resistance.

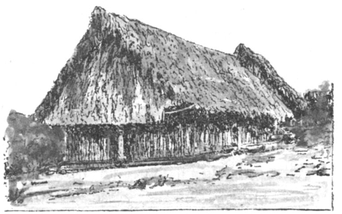

In this way the admiral asked for men to build at Chichén Itzá, and in a short time he built a town, making the houses of wood and the roofs of certain palms and long grass used by the Indians. They say the smallest allotment contained 2000 or 3000 Indians. He also began to fix rules for the natives touching their services to the city, although he was moderate in his demands upon the Indians, and kept his plans hidden for the time.

SEC. XIII. MONTEJO LEAVES YUCATAN WITH ALL HIS PEOPLE AND RETURNS TO MEXICO. HlS SON, FRANCISCO DE MONTEJO, AFTERWARDS PACIFIES YUCATAN.

The Admiral Montejo did not carry out his settlement as he planned ….. of one who has enemies,14 because it was quite far from the sea for entry from and departure for Mexico, and for receiving goods from Spain. The Indians feeling it a hardship to serve strangers where they had been the lords, began to be hostile on all sides, although he defended himself with his horses and men, and killed many. Nevertheless the Indians grew stronger every day, so that he found provisions failing, and at last one night he left the city, leaving a dog tied to the clapper of a bell, near some bread just out of his reach. The day preceding he had harassed the Indians by skirmishes that they might not follow. The dog in trying to reach the bread kept the bell ringing, keeping the Indians uncertain and expecting an attack. When they discovered the ruse, they were furious at what had been played on them, and sought to pursue the Spaniards in all directions, but not knowing what road they had taken. The party that followed in the direction they had gone caught up with the Spaniards, making a great hue and cry as if in a chase of fugitives. Six of the horsemen waited for them in the open and ran many of them down; one of the Indians seized hold of a horse by the leg, and stayed him as if he were a sheep. The Spaniards came to Zilán [Dzilán], a beautiful place, whose chief was a youth of the Chels, and had become a Christian and a friend of the Spaniards; he treated them well. This was near Tikoch, which with all the other towns of that region was under the sway of the Chels; here they remained some months in safety.

The admiral seeing that here they would be unable to receive aid from Spain, and that in case of an uprising by the Indians they would be lost, decided to go to Campeche and Mexico with all his people. From Dzilán to Campeche it was forty-eight leagues, densely populated, so that when he made known his purpose to Namux Chel, the chief of Dzilán, the latter offered to make the road safe and to accompany him. The admiral also arranged with the chief of Yobain, an uncle of him of Dzilán, for the company of his two sons, well disposed youths. Thus with these three youthful cousins, he of Dzilán on horse and the others en croupe, they arrived safely at Campeche and were received there in peace, there taking leave of the Chels who returned to their homes, though the chief of Dzilán died on the way. Thence they departed for Mexico, where Cortés had assigned a quota of Indians to the admiral, notwithstanding his absence.

On arriving at Mexico with his son and nephew, the admiral instituted a search for his wife, Doña Beatrix de Herrera, whom he had married secretly at Sevilla, and a daughter he had had by her, named Beatrix de Mendoza. Some say he refused to recognize her, but Don Antonio de Mendoza, the Viceroy of New Spain, intervened and reconciled them. Thereupon the Viceroy sent him as governor of Honduras, where he married his daughter to the licentiate Alonso Maldonado, president of the Audiencia of the Confines; then after some years they removed to Chiapas, and from there he sent his son, duly empowered, to Yucatan, conquering and reducing it to submission.

This Don Francisco, son of the admiral, was brought up at the court of the Catholic king, and was taken along by his father on his return to the Indies for the conquest of Yucatan; whence he went with him to Mexico. The Viceroy and the Marquis Don Hernando Cortés thought well of him, and he went with the Marquis on the trip to California. On his return the Viceroy made him governor of Tabasco and he married a lady named Doña Andrea del Castillo, who had come to Mexico as a young girl with her parents.

SEC. XIV. STATE OF YUCATAN AFTER THE DEPARTURE OF THE SPANIARDS. DON FRANCISCO, SON OF THE ADMIRAL MONTEJO, RE-ESTABLISHES THE SPANISH RULE IN YUCATAN.

After the departure of the Spaniards from Yucatan, a drought followed in the land, and the corn having been consumed during the wars with the Spaniards they suffered much from famine and were reduced to eating the bark of trees, especially of a certain kind called cumché (kunché), the inside of which is soft and mellow. On account of this famine the Xius of Mani undertook to make a solemn sacrifice to the idols, taking certain male and female slaves to cast into the pool at Chichén Itzá. To do this they had to pass by the town of the Cocom chiefs, their mortal enemies, but thinking that ancient quarrels would be forgotten in such times they sent to ask permission to pass through the country. The Cocoms deceived them with a favorable answer, but having lodged them all together in one great building they set fire to it, and slew those who escaped. From this great wars followed. 15 There was also a plague of locusts for five years, so great that no green thing was left and such a famine ensued that they fell dead on the roads, and when the Spaniards returned they did not recognize the country. However, four good years followed and bettered the situation somewhat.

This Don Francisco set out for Yucatan along the rivers of Tabasco, and entered by the lagoons of Dos Bocas. The first place he touched was Champotón, whose chief Moch-Covoh had received Francisco Hernández and Grijalva so ill. The chief however having died, Don Francisco met no opposition, but was on the contrary supported with his company for two years by the people of the place; during this time he could not advance because of the resistance he encountered. Later he went to Campeche, where he found the inhabitants very friendly, so that with their help and that of the people of Champotón he accomplished the conquest. For their fidelity he promised that the King would reward them, a promise which up to the present time the King has not fulfilled.

Such resistance as he met was not strong enough to prevent Don Francisco from reaching Tiho with his army; here he founded the city of Mérida, and leaving the baggage there he set out to continue the conquest, sending captains in different directions. Don Francisco sent his cousin Francisco, de Montejo to Valladolid to pacify the natives, who had rebelled somewhat, and to settle the city as it now is. In Chectemal [Chetumal] he founded the city of Salamanca [de Bacalar]; Campeche he already had occupied. He established in orderly manner the services of the Indians and the rule of the Spaniards, before the coming of his father the admiral to assume control. The latter on arriving from Chiapas with his wife and household was well received at Campeche, and gave his own name to the city, as San Francisco; and then went on to the city of Mérida.

SEC. XV. CRUELTIES OF THE SPANIARDS TOWARD THE INDIANS. HOW THEY EXCUSED THEMSELVES.

The Indians took the yoke of servitude grievously. The Spaniards held the towns comprising the country well partitioned, but there were some among the Indians who kept stirring them up, and very severe punishments were inflicted in consequence, resulting in the reduction of the population. Several principal men of the province of Cupul they burned alive, and others they hung. Information being laid against the people of Yobain, a town of the Chels, they took the leading men, put them in stocks in a buildings and then set fire to the house, burning them alive with the greatest inhumanity in the world. I, Diego de Landa, say that I saw a great tree near the village upon the branches of which a captain had hung many women, with their infant children hung from their feet. At this town, and another two leagues away called Verey, they hung two Indian women, one a maiden and the other recently married, for no other crime than their beauty, and because of fearing a disturbance among the soldiers on their account; also further to cause the Indians to believe the Spaniards indifferent to their women. The memory of these two is kept both among the Indians and Spaniards on account of their great beauty and the cruelty with which they were killed.

The Indians of the provinces of Cochuah and Chetumal rose, and the Spaniards so pacified them that from being the most settled and populous it became the most wretched of the whole country. Unheard-of cruelties were inflicted, cutting off their noses, hands, arms and legs, and the breasts of their women; throwing them into deep water with gourds tied to their feet, thrusting the children with spears because they could not go as fast as their mothers. If some of those who had been put in chains fell sick or could not keep up with the rest, they would cut off their heads among the rest rather than stop to unfasten them. They also kept great numbers of women and men captive in their service, with similar treatment. It is affirmed that Don Francisco de Montejo was not guilty of any of those cruelties nor approved them, but condemned them severely, yet was unable to do more.16

In their defense the Spaniards urge that being so few in numbers they could not have reduced so populous a country save through the fear of such terrible punishments. They offer the example from the history of the passage of the Hebrews to the land of promise, committing great cruelties by the command of God. On the other hand, the Indians were right in defending their liberty and trusting to the valor of their chiefs, and they thought it would so result as against the Spaniards.

They tell of a Spanish cross-bowman and an Indian archer, who being both very expert sought to kill each other, but neither could take the other unawares. The Spaniard feigning to be off guard, put one knee to the ground, whereupon the Indian shot an arrow that entered his hand and going up the arm separated the bones from each other. At the same moment the Spaniard shot his cross-bow and struck the Indian in the chest. He, feeling himself mortally wounded, cut a withe like an osier only much longer, and hung himself with it that it might not be said that a Spaniard had killed him. Of such instances of valor there are many.

SEC. XVI. STATE OF THE COUNTRY BEFORE THE CONQUEST. ROYAL DECREE IN FAVOR OF THE INDIANS. HEALTH OF THE ADMIRAL MONTEJO. HIS DESCENDANTS.

Before the Spaniards subdued the country the Indians lived together in well ordered communities; they kept the ground in excellent condition, free from noxious vegetation and planted with fine trees. The habitation was as follows: in the center of the town were the temples, with beautiful plazas, and around the temples stood the houses of the chiefs and the priests, and next those of the leading men. Closest to these came the houses of those who were wealthiest and most esteemed, and at the borders of the town were the houses of the common people. The wells, where they were few, were near the houses of the chiefs; their plantations were set out in the trees for making wine, and sown with cotton, pepper and maize. They lived in these communities for fear of their enemies, lest they be taken in captivity; but after the wars with the Spaniards they dispersed through the forests.

Photo by Eric Thompson

Either led on by their evil way or from their bad treatment by the Spaniards, the Indians of Valladolid conspired to slay the Spaniards when they separated to collect the tribute. In one day they killed 17 Spaniards and 400 servants belonging to those they killed and to the others they left alive. Then they sent arms and feet through the whole country in token of what they had done, in order to arouse the rest. These however would not respond, and so the admiral was able to send aid to the Spaniards of Valladolid and to punish the Indians.

The admiral had difficulties with those of Mérida, particularly through the royal decree which deprived the governors of their Indians. An actuary came to Yucatan, took his Indians from the admiral and placed them under the royal protection. After this a Residencia was instituted before the Royal Audience of Mexico, which ordered him before the Royal Council of the Indies in Spain. There he died, full of years and labors, leaving his wife Doña Beatrix richer than himself; also his son Don Francisco de Montejo, married in Yucatan, and his daughter Doña Catalina, married to the licentiate Alonso Maldonado in Honduras, president of the Audience of Honduras and San Domingo in the island of Hispaniola; also Don Juan de Montejo, a Spaniard, and Don Diego, a son by an Indian woman.

Don Francisco, after he turned over the government to his father the admiral, lived in his home as a simple citiezn, so far as public life went, but much honored by all as having conquered, partitioned and ruled the country. He went to Guatemala to close his Residencia and returned to his home. As children he had Don Juan de Montejo, who married Doña Isabel a native of Salamanca, Doña Beatriz de Montejo who married her uncle, his father’s first cousin, and Doña Francisca de Montejo who married Don Carlos de Avellano, a native of Guadalajara. He died after a long sickness, having seen all of his children married.

SEC. XVII. ARRIVAL OF THE SPANISH FRANCISCAN FRIARS IN YUCATAN. PROTECTION THEY GAVE TO THE NATIVES. THEIR CONTESTS WITH THE SPANISH MILITARY ELEMENT.

Friar Jacobo de Testera, a Franciscan, came to Yucatan and began to instruct the Indian children. The Spanish soldiery, however, wanted to use the services of the youths to such an extent that it left no time for them to learn the catechism; they also hated the friars for rebuking their evil conduct toward the Indians. As a result of this friar Jacobo returned to Mexico, where he died. Afterwards friar Toribio Motolinia sent two friars from Guatemala, and from Mexico friar Martin de Hojacastro sent other friars, all of whom settled in Campeche and Mérida, with the approval of the admiral and his son Don Francisco, who built them a monastery at Mérida, as has been stated. They undertook to learn the language, which was very difficult. The one who succeeded the best was friar Luis de Villalpando, who commenced to learn it through signs and small stones; he reduced it to a certain form of grammar and wrote a Christian catechism in the language.* But he suffered many hindrances, both on the part of the Spaniards who, being absolute masters, wanted everything directed to their own profit and tributes, as well as on the part of the Indians who wanted to persist in their idolatries and debaucheries. Especially was the labor heavy because of the Indians being scattered through the forests.17

The Spaniards took it ill that the friars built monasteries; they drove the young Indians from their domains that they might not come to catechism, and twice they burned the monastery at Valladolid, which was built of wood and straw, so that it became necessary for the friars to go and live among the Indians. When the Indians of that province rebelled they wrote to the Viceroy Don Antonio that it was through their fondness for the friars; as to this the Viceroy investigated and proved that the friars had not yet come into the province at the time of the uprising. They spied at night on the friars, causing great scandal with the Indians, pried into their lives, and deprived them of the alms given.

In the face of this danger the friars sent one of their people to a very upright judge, Cerrato, president of Guatemala, to whom he made report of what had happened. The latter, seeing the disorder and unchristian conduct of the Spaniards, how they levied all the tribute they possibly could, against the King’s orders, besides requiring personal service for every sort of labor even to the transport of burdens, established a certain scale of taxation, which while enough was still bearable, and by which it was specified what property should belong to the Indian after his tribute to his master was paid, instead of everything belonging absolutely to the Spaniards.

From this they appealed, and from fear of the tax they took from the Indians even more than before. The friars went back to the Audiencia and also sent to Spain, succeeding so far that the Audiencia of Guatemala sent an Auditor, who fixed the land tax and abolished the personal service. Some of them he forced to marry, breaking up the houses full of women they had. This man was the licentiate Tomás López, a native of Tendilla. All this caused a great increase of the animosity against the friars, infamous libels were spread about them, and the men ceased to attend the masses.

This very hatred caused the Indians to feel well toward the friars, seeing the troubles they took disinterestedly, and securing their freedom; so far did this go that they undertook nothing without consulting the friars and getting, their counsel. And all this aroused further envy against the friars on the part of the Spaniards, who declared they did all this to get the government of the Indies in their own hands and themselves enjoy all the things they had deprived the Spaniards of.18

SEC. XVIII. VICES OF THE INDIANS. STUDIES OF THE FRIARS IN THE LANGUAGE OF THE COUNTRY. THEIR TEACHINGS TO THE INDIANS. CONVERSIONS. PUNISHMENTS OF APOSTATES.

The vices of the Indians were idolatry, divorce, public orgies, and the buying and selling of slaves, and because of being kept from these things they came to hate the friars. The ones however who, apart from the Spaniards, were most averse to the friars were the priesthood, as being a class who had lost their office and its emoluments.

The method taken for indoctrinating the Indians was by collecting the small children of the lords and leading men, and establishing them around the monasteries in houses which each town built for the purpose. Here all in each locality were gathered together, and their parents and relatives brought them their food. Then among these children they gathered them in for catechism, from which frequent visiting many asked for baptism, with much devotion. The children then, after being taught, informed the friars of idolatries and orgies; they broke up the idols, even those belonging to their own fathers; they urged the divorced women and any orphans that were enslaved to appeal to the friars. Even when they were threatened by their people they were not deterred, but answered that it was for their honor, since it was for the good of their souls. The admiral and the royal judges always backed up the friars in gathering the Indians to catechism, and in punishing those who returned to their old life. At first the lords gave up their children with ill grace, fearing that they wished to make little slaves of them as the Spaniards had done, so that they gave many young slaves in place of their own children; but when they understood the matter they sent them with good grace. In this way the children made remarkable progress in the schools, and the others in the catechism.

They learned to read and write in the Indian tongue, forming a grammatical system, so as to study it like the Latin. They found that six of our letters, D, F, G, Q, R, S, were not used or needed at all. Others however they had to double, and some to add, in order to understand the many meanings of some words. Thus pa means  to open,’ and ppa, spoken by tightly compressing the lips, means

to open,’ and ppa, spoken by tightly compressing the lips, means  to break’; tan means

to break’; tan means  lime,’ or

lime,’ or  ashes,’ and tan (t’an) uttered forcibly between the tongue and upper teeth means a

ashes,’ and tan (t’an) uttered forcibly between the tongue and upper teeth means a  word,’ or

word,’ or  to speak.’ Apart from having different characters for these things, there was no need for inventing new forms of letters, but only to make use of the Latin ones, common to all.

to speak.’ Apart from having different characters for these things, there was no need for inventing new forms of letters, but only to make use of the Latin ones, common to all.

They also gave orders that they should leave their homes in the forests and gather as formerly in proper settlements, that they might be more easily instructed and not make the fathers so much trouble. For their support they also made contributions at the paschal and other festivals, and also contributed to the churches through two aged Indians, appointed for the purpose. Thus they supplied the needs whenever they went visiting among them, and also adorned the churches.

After the people had been thus instructed in religion, and the youths benefitted as we have said, they were perverted by their priests and chiefs to return to their idolatry; this they did, making sacrifices not only by incense, but also of human blood. Upon this the friars held an Inquisition, calling upon the Alcalde Mayor for aid; they held trials and celebrated an Auto, putting many on scaffolds, capped, shorn and beaten, and some in the penitential robes for a time. Some of the Indians out of grief, and deluded by the devil, hung themselves; but generally they all showed much repentance and readiness to be good Christians.19

SEC. XIX. ARRIVAL OF BISHOP TORAL AND RELEASE OF THE IMPRISONED INDIANS. VOYAGE OF THE PROVINCIAL OF SAN FRANCISCO TO SPAIN TO JUSTIFY THE CONDUCT OF THE FRANCISCANS.

At this point fray Francisco Toral, a Franciscan friar, and a native of Ubeda, who had been for twenty years in Mexico and then come as Bishop of Yucatan, arrived at Campeche. He, giving ear to the charges of the Spaniards and the complaints of the Indians, undid the friars’ work, and ordered the prisoners released. The provincial feeling himself aggrieved thereat, determined to go to Spain, after first lodging complaint in Mexico. He thus arrived at Madrid, where the Council of the Indies censured him severely for having usurped the office of bishop and inquisitor. In defense he asserted the privileges held by his order in those territories by the grant of Pope Adrian, at the instance of the Emperor; as well as the support ordered to be given him by the Royal Audience of the Indies, the same as given to the bishops. These defenses alienated the members of the Council yet more, and they decided to refer him and his papers, as well as those which had been sent by the Bishop, against the friars, to fray Pedro de Bobadilla, Provincial of Castile, to whom the King wrote commanding investigation and the performance of justice. Fray Pedro, being ill, committed the examination of the affair to Fray Pedro de Guzmán, of his own order, a man learned and experienced in inquisitorial matters.

To him, then, were presented the opinions of seven learned persons of the kingdom of Toledo, namely: Don fray Francisco de Medina and fray Francisco Dorantes, of the Franciscan order; master frayle Alonso de la Cruz, an Augustinian friar who had spent thirty years in the Indies; the licentiate Tomás López who had been an Auditor in Guatemala in the New Kingdom, as well as a judge in Yucatan; D. Hurtado, professor of canon law; D. Méndez, professor of the Sacred Scriptures; and D. Martinez, Scotist professor at Alcalá. These declared that the Provincial had acted rightly in the matter of the Auto and other things for the punishment of the Indians. This being reviewed by fray Francisco de Guzmán, he wrote fully upon it to the Provincial, fray Pedro de Bobadilla.

The Indians of Yucatan deserve that the King should favor them for many reasons, and especially for the readiness they have shown in his service. While he was occupied in Flanders the princess Doña Juana his sister, who was then regent of the kingdom, wrote a letter asking the assistance of those in the Indies. This an Auditor of Guatemala bore to Yucatan, and having gathered the chiefs together, he directed a friar to preach upon what they owed to his majesty, and what was asked of them. Having finished his discourse, the Indians rose to their feet and said that they recognized their obligation to God for having given them so noble and Christian a king, and that they were grieved not to live where they might serve him in person; wherefore whatever in their poverty they had that he desired, they placed at his service; and if that did not suffice, they would sell their children and wives.

SEC. XX. CONSTRUCTION OF THE HOUSES OF YUCATAN. OBEDIENCE AND RESPECT OF THE INDIANS FOR THEIR CHIEFS. HEADGEAR AND WEARING OF GARMENTS.

In building their houses their method was to cover them with an excellent thatch they have in abundance, or with the leaves of a palm well adapted to that purpose, the roof being very steep to prevent its raining through. They then run a wall lengthways of the whole house, leaving certain doorways into the half which they call the back of the house, where they have their beds. The other half they whiten with a very fine whitewash, and the chiefs also have beautiful frescos there. This part serves for the reception and lodging of guests, and has no doorway but is open along the whole length of the house. The roof drops very low in front as a protection against sun and rain; also, they say, the better to defend the interior from enemies in case of necessity.

Phono by Eric Thompson

The common people build the chiefs’ dwellings at their own expense. The houses having no doors, it is held a grave offense to do any wrong to another’s house; in the back, however, they have a small door for household uses. They sleep on beds made of small rods, covered with mats, and with their mantles of cotton as covering. In the summer they sleep in the front part of the house on the mats, especially the men. Away from the house the entire village sows the fields of the chief, cares for them, and harvests what is required for him and his household; and whenever they hunt and fish, or at the salt gathering time, they always give a part to the chief; in these matters everything is always in common.

If the chief should die his eldest son would succeed him, but the others would always be much respected, favored and held as lords. The leading men, lower than the chief, are favored in all these matters according to who they are, or the favor shown them by the chief. The priests live upon their benefices and offerings. The chiefs govern the town, settling suits, ordering and adjusting the affairs of the commonwealths, doing all through the hands of the leading men. These latter are much honored and obeyed, especially the wealthy, the chiefs visiting them and holding court at their houses fcr the settlement of affairs and business, this being done principally at night.

Whenever the chiefs leave the town they have a great company in attendance, and the same when they leave their houses.

The Indians of Yucatan are people of good physique, tall, robust and of great strength, and commonly are all bow-legged from having in their infancy been carried astride the mother’s hip when they are taken somewhere. It was held as a grace to be cross-eyed, and this was artificially brought about by the mothers, who in infancy suspended a small plaster from the hair down between the eyebrows and reaching the eyes; this constantly binding, they finally became cross-eyed. They also had their heads and foreheads flattened from infancy by their mothers. Their ears were pierced for earrings and much scarified from the sacrifices. They did not grow beards and say that their mothers were used to burn their faces with hot cloths to prevent the growth. Nowaday beards are grown, although they are very rough, like hogs’ bristles.

They allowed their hair to grow like the women; on top they ringed it, making a good tonsure. Thus it grew long below but short on the crown; it was braided and wound around the head, with an end left behind like a queue. All the men used mirrors, and the women not; and to call a man a cuckold they said his wife had put the mirror in his hair behind his head. They bathed a great deal, not troubling to cover themselves before the women, except such as they might do with the hand. They were devoted to perfumes, having bouquets of flowers and odorous plants, arranged with much care and art. They painted their faces and bodies red, disfiguring themselves, though to them it seemed handsome.

Their clothing was a strip of cloth a hand broad that served for breeches and leggings, and which they wrapped several times about the waist, leaving one end hang in front and one behind. These ends were embroidered by their wives with much care and with featherwork. They wore large square mantles, which they threw over the shoulders. They wore sandals of hemp or deerskin tanned dry, and then no other garments.20

SEC. XXI. FOOD AND DRINK OF THE INDIANS OF YUCATAN.

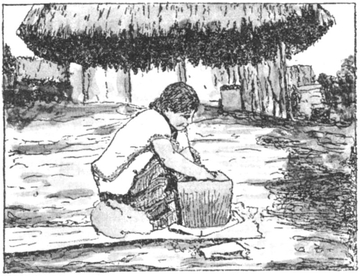

Their principal sustenance is maize, of which they prepare various dishes and drinks; and even drunk as they do it, it serves as their food and drink. The Indian women put the maize to soak the night before in lime and water, and in the morning it is soft and half-cooked, having in the process lost the husk and nib. They next grind it on stones, and when half ground make it into great balls and loads for the use of laborers, travelers and sailors. In that shape it keeps for several months, except for souring. Of this they then take a lump and dissolve it in a vessel or gourd formed by the rind of a fruit that grows on a tree, whereby God has provided them with vessels; out of this they drink the liquor and then eat the rest, it being of excellent taste and very nourishing. From the maize that is more fully ground they take away the milk and thicken it at the fire, making a sort of curd for morning use; and this they drink hot. Upon what is left from the morning they put water for drinking through the day, since they are not accustomed to drink water alone. They also toast the maize and then grind and mix it with water into a very refreshing drink, putting into it a little Indian pepper or cacao.