PART TWO

SEC. XXXIV. COUNT OF THE YUCATECAN YEAR. CHARACTERS OF THE DAYS. THE FOUR BACABS AND THEIR NAMES. GODS OF THE  UNLUCKY ’ DAYS.

UNLUCKY ’ DAYS.

The sun does not sink or go away far enough in this land of Yucatan for the nights to become longer than the days; thus in their full maximum, from San Andrés to Santa Lucia [Nov. 30 to Dec. 13] they are equal, and then they begin to lengthen. To know the hour of the night the natives governed themselves by the planet Venus, the Pleiades and the Twins. During the day they had terms for midday, and for different sections from sunrise to sunset, according to which they recognized and regulated their hours for work.

They had their perfect year like ours, of 365 days and 6 hours, which they divided into months in two ways. In the first the months were of 30 days and were called U, which signifies the moon, and they counted from the rising of the new moon until it disappeared.

In the other method the months had 20 days, and were called uinal hunekeh; of these it took eighteen to complete the year, plus five days and six hours. Out of these six hours they made a day every four years, so that they had a 366-day year every fourth time.27

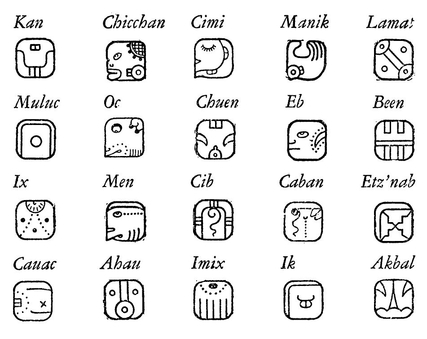

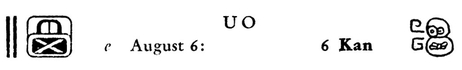

For these 360 days they had 20 letters or characters by which to designate them, without assigning names to the five supplementary days,27 as being sinister and unlucky. The letters are as follows, each with its name above to understand their correlation with ours.

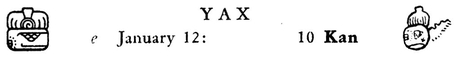

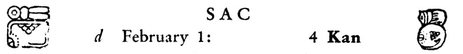

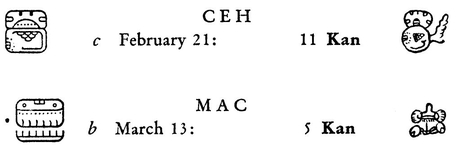

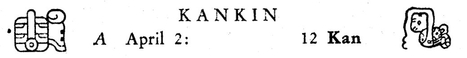

I have already related that the Indian method of counting was from five to five, and four fives making 20; thus then from these 20 characters they take the first of each set of five, so that each of these serves for a year as do our Dominical letters, being the initials days of the various 20-day months (or uinals). Thus:

Among the multitude of gods worshipped by these people were four whom they called by the name Bacab. These were, they say, four brothers placed by God when he created the world, at its four corners to sustain the heavens lest they fall. They also say that these Bacabs escaped when the world was destroyed by the deluge. To each of these they give other names, and they mark the four points of the world where God placed them holding up the sky, and also assigned one of the four Dominical letters to each, and to the place he occupies; also they signalize the misfortunes or blessings which are to happen in the year belonging to each of these, and the accompanying letters.

The evil one, who has in this as in many other cases deceived them, fixed for them the services and offerings that had to be made in order to evade these misfortunes. Thus if they failed to occur, they said it was because of the ceremonies performed; but if they did come to pass, the priests made the people believe that it was because of some error or fault in the ceremonies,

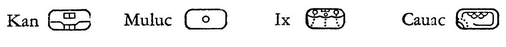

The first of these Dominical letters, then, is Kan. The year served by this letter had as augury that Bacab who was otherwise called Hobnil, Kanal-bacab, Kan-pauahtun, Kan-xibchac. To him belonged the South.

The first of these Dominical letters, then, is Kan. The year served by this letter had as augury that Bacab who was otherwise called Hobnil, Kanal-bacab, Kan-pauahtun, Kan-xibchac. To him belonged the South.

The second letter, or Muluc, marked the East, and this year had as its augury the Bacab called Can-sicnal, Chacal-bacab, Chac-pauahtun, Chac-xibchac.

The second letter, or Muluc, marked the East, and this year had as its augury the Bacab called Can-sicnal, Chacal-bacab, Chac-pauahtun, Chac-xibchac.

The third letter is Ix, and the augury for this year was the Bacab called Sac-sini, Sacal-bacab, Sac-pauahtun, Sac-xibchac, marking the North.

The third letter is Ix, and the augury for this year was the Bacab called Sac-sini, Sacal-bacab, Sac-pauahtun, Sac-xibchac, marking the North.

The fourth letter is Cauac, its augury for that year being the Bacab called Hosan-ek, Ekel-bacab, Ek-pauahtun, Ek-xibchac; this one marked the West.

The fourth letter is Cauac, its augury for that year being the Bacab called Hosan-ek, Ekel-bacab, Ek-pauahtun, Ek-xibchac; this one marked the West.

In whatever ceremony or solemnity these people celebrated for their gods, they always began by driving away the evil spirit, in order the better to perform it. This exorcism was at times by prayers and benedictions they had for this purpose, and at other times by services, offerings and sacrifices which they performed for that end. In order to celebrate the solemnity of the New Year with the greatest rejoicing and dignity, these people, with their false ideas, made use of the five supplementary days, which they regarded as  unlucky,’ and which preceded the first day of their new year, in order to put on a great fiesta for the above Bacabs and the evil one, to whom they gave four other names, as they had done to the Bacabs; these names were: Kan-uvayeyab, Chac-uvayeyab, Sac-uvayeyab, Ek-uvayeyab.28 These ceremonies and fetes being over, and the evil one driven away, as we shall see, they began their new year.

unlucky,’ and which preceded the first day of their new year, in order to put on a great fiesta for the above Bacabs and the evil one, to whom they gave four other names, as they had done to the Bacabs; these names were: Kan-uvayeyab, Chac-uvayeyab, Sac-uvayeyab, Ek-uvayeyab.28 These ceremonies and fetes being over, and the evil one driven away, as we shall see, they began their new year.

SEC. XXXV. FESTIVALS OF THE ‘UNLUCKY ’ DAYS. SACRIFICES FOR THE BEGINNING OF THE NEW YEAR KAN.

In all the towns of Yucatan it was the custom to have at each of the four entrances to the town two heaps of stones, one in front of the other; that is, at the east, west, north and south; and here they celebrated the two festivals of the  unlucky’ days, in the following manner.

unlucky’ days, in the following manner.

For the year whose Dominical letter was Kan, the augury was Hobnil, and they say that both of these ruled the South. In this year, then, they made an image or clay figure of the demon they called Kan-uvayeyab and carried it to the piles of stone they had erected at the South. They chose a leading man of the town, at whose house was celebrated this fiesta on these days, and then they made a statue of a demon whom they called Bolon-tz’acab, which they set at the house of the principal, erected in a public spot to which all might come.

This being done, the chiefs, the priest and the men of the town, assembled and having the road clean and prepared, with arches and green branches, as far as the two heaps of stone where the statue was, there they gathered most devoutly; on arriving there the priest incensed the statue with forty-nine grains of ground maize, mixed with incense; then the nobles put their incense into the brazier of the idol, and incensed it. The ground maize alone was called sacah, and that of the lords chahalté.

Thus incensing the image, they cut off the head of a fowl, and presented it as an offering. When all had done this, they placed the image on a wooden standard called kanté, placing on his shoulders an angel as a sign of water and of a good year, and these angels they painted so as to make them frightful in appearance. Then they carried it with much rejoicing and dancing to the house of the principal, where there was the other statue of Bolon-tz’acab.

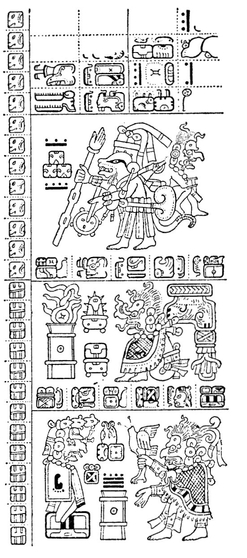

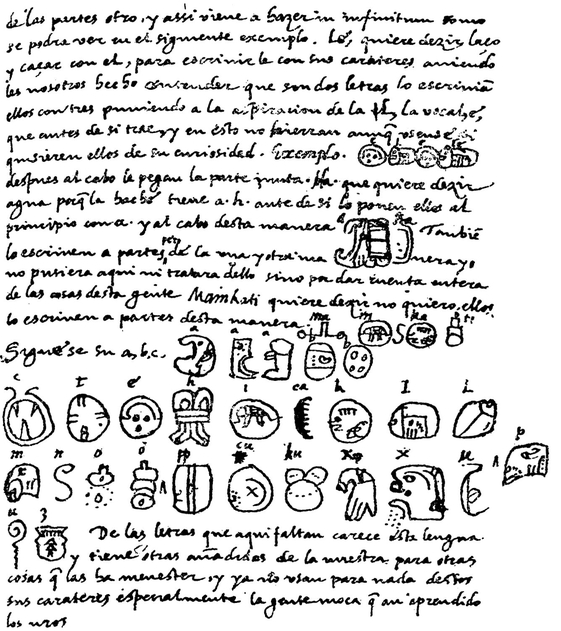

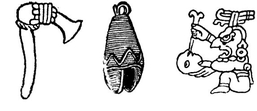

The illustration is a page of the Dresden codex, showing the Kan-uvayeyab ceremonies at the East.

From the house of this principal they brought out to the road, for the chiefs and the priest, a drink made of 415 grains of toasted maize (which they call picula kakla, of which all drank. On arrival at the house they set the image they were carrying in front of the statue of the demon they had there, and then made many offerings of food and drink, of meat and fish; these offerings were given to whatever strangers there were there; and to the priest they gave a leg of venison.

Others drew blood by cutting their ears and anointing therewith a stone image they had there, of the demon Kanal-acantun. They molded a heart of bread and another of calabash seeds, and offered those to the image of the demon Kan-uvayeyab. They kept this statue and image through those fateful days, and perfumed them with their incense, and with the ground maize and incense. They believed that if they did not perform these ceremonies, certain sicknesses would come on them in the ensuing year. When these fatal days were over they took the statue of Bolon-tz’acab to the temple, and the image to the eastern entrance where the next year they would go for it; there they left it and went to their houses to do what was their part in celebrating the new year.

These ceremonies over, and the evil spirit exorcised according to their deluded beliefs, they looked on the coming year as a good one, because it was ruled by the character Kan and the bacab Hobnil; and of him they said that in him there was no sin as in his brothers, and because of that no evils would come upon them. But since they often did so come, the evil one provided ceremonies therefor, so that when they happened they might throw the blame on the ceremonies or celebrants; and thus they continued always deluded and blind.

It was then commanded to make an idol called Itzamná-kauil, and place it in the temple. Then in the temple court they burned three balls of a milk or resin they called kik (rubber), while sacrificing a dog or a man; this they did keeping the same procedure I have described in chapter 100 (Sec. xxvii), except that in this case the method of the sacrifice differed. In the temple court they erected a great pile of stones, and then placed the dog or the man to be sacrificed on something much higher, from which they threw him, tied, upon the pile below; there the attendants seized him and with great swiftness drew out his heart, raised it to the new idol, and offered it between two plates. They offered other gifts of food, and in this festival there danced old women of the town, chosen therefor, clothed in certain vestures. They say that an angel descended and received this sacrifice.

SEC. XXXVI. SACRIFICES FOR THE NEW YEAR OF THE CHARACTER MULUC. DANCES OF THE STILT-WALKERS. DANCE OF THE OLD WOMEN WITH TERRACOTTA DOGS.

In the year whose dominical letter was Muluc the augury was Cansicnal. On this occasion the chiefs and the priest selected a president to care for the festival, after which election they made an image of the demon as they had done in the previous year, and which they called Chac-uvayeyab, and carried this to the piles of stone at the East, where they had left the other one the year before. They also made a statue of the idol called Kinchahau, and placed it in the house of the president in a convenient place; from there, with the road all cleaned and dressed, they all proceeded together for their accustomed devotions before the god Chac-uvayeyab.

On arriving the priest perfumed it with 53 grains of the ground maize, with the incense, which they call sacah. The priest gave this to the chiefs, who put in the brazier more incense, of the kind called chahalté; then they cut off a fowl’s head, as before, and taking the image on a wooden standard called chacté, they carried it very devoutly, while dancing certain war-dances they call holcan-okot, batel-okot. During this they brought to the road for the chiefs and principal men their drink made from 380 grains of maize, toasted as before.

When they had arrived at the house of the president they put this image in front of the statue of Kinch-ahau, and made all their offerings to it, which were then distributed like the rest. They offered to the image bread formed like the yolks of eggs, others like deer’s hearts, and another made of dissolved peppers. Many of them drew blood from their ears, and with it anointed the stone they had there, of the god Chac-acantun. They took boys and forcibly drew blood from their ears, by blows. They kept this statue and the image until the fatal days were passed, meanwhile burning their incense. When the days were over, they took the image to the part of the North, where next year they had to go to seek it; the other they took to the temple, and then went to their houses to care for the works of the new year. If they did not do all these things, they feared the coming especially of eye troubles.

The dominical letter of this year being Muluc, the Bacab Can-sicnal ruled, whence they held it a favorable year, for they said he was the best and greatest of these Bacab gods; for this they put him first in their prayers. Yet for all this the evil one caused them to make an idol called Yaxcoc-ahmut, which they placed in the temple and took away the old images; then they erected in the temple court a stone block on which they burned their incense, and a ball of the resin or milk kik, with a prayer there to the idol, asking relief for the ills they feared for the coming year; these were a scarcity of water, buds (hijos) on the maize, and the like. To gain this protection the evil one ordained offerings of squirrels and an unembroidered cloth, which was to be woven by old women whose office it was to appease Yaxcoc-ahmut.

In spite of this being held a good year, they were still menaced with many other evils and bad signs, if they did not perform the sacrifices ordained. These were having dances on tall stilts, with offerings of heads of turkeys, bread and drinks made of maize. They had to offer clay dogs with bread on their backs, the old women dancing with them in their hands, and sacrificing a virgin puppy with black back. The devotees had to draw their blood and anoint the stone of Chac-acantun with it. This ceremony and sacrifice they regarded as acceptable to their god Yaxcoc-ahmut.

SEC. XXXVII.SACRIFICES FOR THE NEW YEAR WITH THE SIGN IX. SINISTER PROGNOSTICS, AND MANNER OF CONJURING THEIR EFFECTS.

In the year whose dominical letter was Ix and the augury Sac-sini, after the election of the president for the celebration of the festival, they made an image of the demon called Sac-uvayeyab, and carried it to the piles of stone at the North, where they had left the other one the year before. They then made a statue of the god Itzamnáand set that in the president’s house, then all together, with the roadway prepared, they went devoutly to the image of Sac-uvayeyab. On arrival they offered incense in the usual way, cut off the head of a fowl, and placed the image on a wooden stand called Sac-hia, and then carried it ceremoniously and with dances they called aleab-tan kam-ahau.29They brought to the road the usual drinks, and on arriving at the house they set this image before the statue of Itzamná, and there made their offerings, and distributed them; to the statue of Sac-uvayeyab they offered the head of a turkey, pates of quail with other things, and their drink.

Others drew blood and with it anointed the stone of the demon Sac-acantun, and they then kept the idols as they had done the year before, offering them incense until the last day. Then they carried Itzamná to the temple and Sac-uvayeyab to the place of the West, to leave him there to be gotten the next year.

The evils the Indians feared for the ensuing year if they were negligent in these ceremonies were loss of strength, fainting and ailments of the eyes; it was held a bad year for bread and a good one for cotton. And this year bearing the dominical Ix, and which the Bacab Sac-sini ruled, they held as ill-omened, with many evils destined to occur; for they said there would be great shortage of water, many hot spells that would wither the maize fields, from which would follow great hunger, and from the hunger thefts, and from the thefts slavery for those who had incurred that penalty therefor. From this would come great discords, among themselves or with other towns. They also said that this year would bring changes in the rule of the chiefs or the priests, because of the wars and discords.

Another prognostic was that some men who should seek to become chiefs would fail in their aim. They also said that the locusts would come, and depopulate many of their towns through famine. What the evil one ordained that they should do to avert these ills, some or all of which were due to fall on them, was to make an idol of Kinch-ahau Itzamná, which they should put in the temple, where they should burn incense and make many offerings and prayers to the god, together with the drawing of their blood for the anointing of the stone of the demon Sac-acantun. They danced much, and the old women danced as was their custom; in this festival they also built a new oratorio for the demon, or else renewed the old, and gathered there for sacrifices and offerings to him, all going through a solemn revel; for this festival was general and obligatory. There were some very devout persons who of their own volition made another idol like the above, and placed it in other temples, where they made offerings and revels. These revels and sacrifices were held to be very acceptable to the idols, and as remedial for freeing them from the ills indicated as to come.

SEC. XXXVIII. SACRIFICES OF THE NEW YEAR OF THE LETTER CAUAC. THE EVILS PROPHESIED AND THEIR REMEDY IN THE DANCE OF THE FIRE.

In the year whose dominical was Cauac and the augury Hosan-ek, after the election of the one to serve as president had been made, they made an image of the demon named Ek-uvayeyab, and carried this to the piles of stone on the West, where they had left the other the year before. They also made a statue of a demon called Vacmitun-ahau, which they put in the president’s house in a convenient place, and from there went all together to where the image of Vacmitun-ahau stood, having the road thither all properly prepared. On arriving the priest and the chiefs offered incense, as they were accustomed, and cut off the head of a fowl. After this they took the image on a standard called yax-ek, placing on the back of the image a skull and a corpse, and on top a carnivorous bird called kuch [ vulture ’], as a sign of great mortality, since they regarded this as a very evil year.

vulture ’], as a sign of great mortality, since they regarded this as a very evil year.

They then carried it thus with their sentiment and devotion, dancing various dances, among which was one like the cazcarientas, which they thus called the xibalba-okot, meaning the dance of the devil. The cup-bearers brought to the road the drink of the chiefs, which they drank and came to the place of the statue Vacmitun-ahau, and then they placed before it the image they brought. Thereupon commenced the offerings, the incense, and the prayers, while many drew blood from many parts of the body, to anoint the stone of the demon called Ekel-acantun; thus the fatal days passed, after which they carried Vacmitun-ahau to the temple, and Ek-uvayeyab to the place of the South, to receive it the next year.

This year whose sign is Cauac and which was ruled by the bacab Hosan-ek , they held as one of mortality and very bad, according to the omens; for they said that many hot spells would kill the maize fields, while the multitudes of the ants and the birds would eat up the seeds that had been sown; but since this would not happen in all parts, in some places they would lack food, and in others have it, though with heavy labor. To avoid this the evil one caused them to make four demons called Chichac-chob, Ekbalam-chac, Ahcanuol-cab, Ahbuluc-balam, and set them in the temple where they should offer incense, and burn two balls of the milk or resin called kik, together with some iguanas, and bread, a miter, a bunch of flowers, and one of their precious stones. After this, to celebrate the festival, they made a great vault of wood, filling it aloft and on the sides with firewood, leaving doors to enter and go out. Then the most of the men took each two bundles of rods, very dry and long, tied together, and a singer standing on top of the firewood sang and made sound with one of their drums, while those below danced in complete unison and devotion, entering and leaving the doors of that wooden vault; dancing thus until the evening, each left there his bundle, and they then went home to rest and eat.

When the night came on they returned, and with them came a great crowd, because this ceremony was held in great regard. Each then took his bundle of rods, lit it, and each for himself put fire to the firewood, which burned high and quickly. When only the coals were left, they smoothed and spread them out; then those who had danced having come together, some of them began to walk unshod and naked from one side to the other across the hot coals; some of these came off with no lesions whatever, some came burned or half burned. In this way they believed to lie the remedy against the ills and bad auguries, and that this was the service most acceptable to their gods. After this they went off to drink and get intoxicated, for this was called for by the customs of the festival, and by the heat of the fire.

SEC. XXXIX.THE AUTHOR’S EXPLANATION AS TO VARIOUS THINGS IN THE CALENDAR. His PURPOSE IN GIVING THESE THINGS NOTICE.

Together with the characters of the Indians shown above in our chapter 100 (Sec. xxxiv), they gave names to the days of their months, and from all the months together they made up a kind of calendar, by which they regulated their festivals, their counting and contracts as business, as we do ours; save that the first day of their calendar was not the first day of their year, but came much later; this being the result of the difficulty with which they counted the days of the months all together, as will be seen in the Calendar itself we shall give herein later. The reason is that although the signs and names of the days of their months are twenty, they were used to count them from 1 to 13; after the 13 they return to 1 again, thus dividing the days of the year into twenty-seven thirteens or triadecads, plus nine days, without the supplementary ones.

With these periodical returns and the complicated count, it is a marvel to see the freedom with which they know how to count and understand things. It is notable that the dominical always falls on the first day of their year, without fail or error, no other of the twenty ever taking that position. They also used this way of counting to bring out by the aid of these characters a certain other count they had for their ages; also other matters which, although they were important for them, do not concern us much here. We shall therefore be content with saying that the character or letter with which they began their count of the days or Calendar is called Hun Imix (One Imix), which is this: and which has no fixed day on which it must fall. For each modifies  its own count,and with all this the dominical letter as they have it never fails to fall on the first day of the following year.

its own count,and with all this the dominical letter as they have it never fails to fall on the first day of the following year.

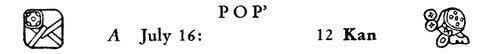

Among these people the first day of the year always fell upon our 16th of July, and was the first of their month Popp. Nor is it to be wondered at that this people, however simple as we have found them in many ways, also had ability in these matters and ideas such as other nations; for in the gloss on Ezekiel we find that according to the Romans January began the year, according to the Hebrews April, according to the Greeks March, and according to the Orientals October. But, although they began their year in July, I put their calendar here in the order of ours, and parallel, so that our letters and theirs will come noted, our months and theirs, together with their above-mentioned count of the thirteens, placed in the order of their progression. 30

And since there is no need for putting the calendar in one place and the festivals in another, I shall place in each of the months its festivals and the observances and ceremonies with which they celebrated it. Thus I shall do as I before promised, giving their calendar and with it telling of their fasts and ceremonies wherewith they made their idols of wood, and other things; all of these things and what else I have told of these people serving no other purpose than to praise the divine goodness which so has permitted and has seen well to remedy in our times. This in order that, in recording them, with Christian entrails we pray Him for their preservation and progress in true Christianity; and that those whose charge this is may promote and aid this end, so that neither to this people for their sins, nor to ourselves, may there be lacking help; nor may they fail in what has been begun and so return to their misery and vomitings of errors, thus falling into worse case than before, returning the evil ones we have been able to drive out of their souls, out of which with so laborious care we have been able to drive them, cleansing them and sweeping out their vices and evil customs of the past. And this is not a vain hope, when we see the perdition which after so many years is to be seen in great and very Christian Asia, in the good, Catholic and very august Africa, and the miseries and calamities which today our Europe suffers, and where in our nation and houses we might say that the evangelical prophecies over Jerusalem have been fulfilled, where her enemies encircle her and crowd her almost to the earth. All of this God already had permitted for us, as we stand, were it not that his Church cannot pass, neither that which is said concerning her: Nisi Dominus reliquisset semen, sicut Sodoma fuis-semus.

SEC. XL. MONTHS AND FESTIVALS OF THE YUCATECAN CALENDAR.

The first day of Popp. which is the first month of the Indians, was its New Year, a festival much celebrated among them, because it was general, and of all; thus the whole people together celebrated the festival for all their idols. To do this with the greater solemnity, on this day they renewed all the service things they used, as plates, vases, benches, mats and old garments, and the mantles around the idols. They swept their houses, and threw the sweepings and all these old utensils outside the city on the rubbish heap, where no one dared touch them, whatever his need.

For this festival the chiefs, the priest and the leading men, and those who wished to show their devoutness, began to fast and stay away from their wives for as long time before as seemed well to them. Thus some began three months before, some two, and others as they wished, but none for less than thirteen days. In these thirteen days then, to continence they added the further giving up of salt or pepper in their food; this was considered a grave penitential act among them. In this period they chose the chacs, the officials for helping the priest; on the small plaques which the priests had for the purpose, they prepared a great number of pellets of fresh incense for those in abstinence and fasting to burn to their idols. Those who began these fasts, did not dare to break them, for they believed it would bring evil upon them or their houses.

When the New Year came, all the men gathered, alone, in the court of the temple, since none of the women were present at any of the temple ceremonies, except the old women who performed the dances. The women were admitted to the festivals held in other places. Here all clean and gay with their red-colored ointments, but cleansed of the black soot they put on while fasting, they came. When all were congregated, with the many presents of food and drink they had brought, and much wine they had made, the priest purified the temple, seated in pontifical garments in the middle of the court, at his side a brazier and the tablets of incense. The chacs seated themselves in the four corners, and stretched from one to the other a new rope, inside of which all who had fasted had to enter, in order to drive out the evil spirit, as I related in chapter 96 (Sec. XXVI). When the evil one had been driven out, all began their devout prayers, and the chacs made new fire and lit the brazier; because in the festivals celebrated by the whole community new fire was made wherewith to light the brazier. The priest began to throw in incense, and all came in their order, commencing with the chiefs, to receive incense from the hands of the priest, which he gave them with as much gravity as if he were giving them relics; then they threw it a little at a time into the brazier, waiting until it ceased to burn.

After this burning of the incense, all ate the gifts and presents, and the wine went about until they became very drunk. Such was the festival of the New Year, a ceremony very acceptable to their idols. Afterwards there were others who celebrated this festival, in this month Pop’, among their friends, and with the chiefs and the priests, these latter being always first in their banquets and drinking.

In the month Uo the priests, and the physicians and sorcerers (who were one) began, with fasting and the rest, to prepare to celebrate another festival. The hunters and fishermen began to celebrate on the 7th of Sip, each celebrating for himself on his own day. First the priests celebrated their fete, which was called Pocam [‘the washing’]; gathered in their regalia in the house of the chief, they first cast out the evil spirit as was their custom; after that they brought out their books and spread them upon the fresh leaves they had prepared to receive them. Then with many prayers and very devoutly they invoked an idol they called Kinch-ahau Itzamná, who they said was the first priest, offered him their gifts and burned the pellets of incense upon new fire; meanwhile they dissolved in a vase a little verdigris and virgin water which they say was brought from the forests where no woman had been, and anointed with it the tablets of the books for their purification. After this had been done, the most learned of the priests opened a book, and observed the predictions for that year, declared them to those present, preached to them a little enjoining the necessary observances, and then assigning this festival for the coming year to the priest or chief who should then perform it; if he should die within the year his sons were under obligation to carry it for the deceased. After this they ate the gifts and food that had been brought, and drank until they were filled; thus they ended this festival, in which at times they gave the dance okot-uil.

On the following day the physicians and sorcerers gathered in the house of one of them, with their wives. The priest exorcised the evil spirit. After that they opened the wrappings of their medicines, in which they had brought foolish things, including (each of them) small idols of the goddess of medicine whom they called Ixchel, from whom this festival was called Ihcil-Ixchel, as well as certain little stones called am, and with which it was their custom to cast the lots. Then with great devotion they invoked the gods of medicine by their prayers, these being called Itzamná, Cit-bolontun and Ahau-chamahes, the priests offering the incense burned in braziers with new fire; meanwhile the chacs covered the idols and the small stones with a blue bitumen like that of the books of the priests.

After this each one wrapped up the implements of his office, and taking the pouch on his back all danced a dance they called Chantuniah. After the dance the men sat by themselves, and the women by themselves; and after putting over the festival until the next year, they ate the presents, and became drunk without regard; except the priests, who as they say refrained from the wine, to drink it when alone and at their pleasure.

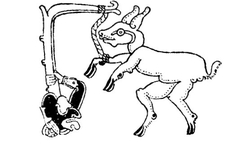

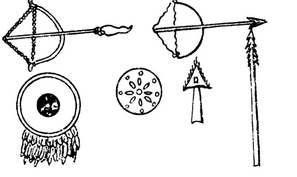

The next day the hunters gathered in the house of one of them, bringing their wives, like the others; the priests came and exorcised the evil spirit in their manner. Then they placed in the center the materials prepared for the sacrifice of the incense and the new fire, and the blue bitumen. Then with worship the hunters invoked the gods of the chase, Acanum, Suhuy-sib, Sipitabai, and others; they distributed the incense, which they then threw in the brazier; while it burned each one took an arrow and the skull of a deer, which the chacs anointed with the blue pitch; some then danced with these, as anointed, in their hands, while others pierced their ears and others their tongues, and passed seven leaves of a broadish plant called ac, through the holes. When this was done, the priest first and then the officers of the festival at once made their offerings, and thus dancing they served the wine and became drunk.

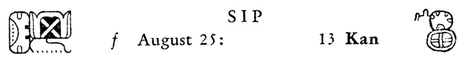

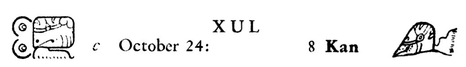

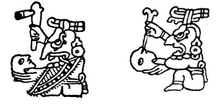

The first two figures on this page are from the Dresden Codex, showing Ixchel as goddess of medicine; of the rest, from the Madrid codex, in one the god Ekchuah traps the deer; next a vulture or kuch preys on the slain deer, and a hunter strikes a rattlesnake as it bites him; in the next a peccary, citàm, is caught in a spring trap, and in the next an aspersarium, previously described, is being used in what is known as the  chapter of the bees.’ A little further on, under the month Xul, is shown one of the very handsome handled incense burners, of which a number of specimens have been found.

chapter of the bees.’ A little further on, under the month Xul, is shown one of the very handsome handled incense burners, of which a number of specimens have been found.

We probably have here a survival from an earlier adjustment of the calendar, as shown both by the month-names and the ceremonies. Xul means  end, termination.’ and on the l6th they created new fire, and continued offerings and other ceremonies for the last five days of the month, paralleling those later carried on before the New Year beginning the 1st of Pop’. Kin means ’ sun, day, time,

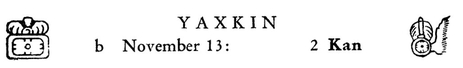

end, termination.’ and on the l6th they created new fire, and continued offerings and other ceremonies for the last five days of the month, paralleling those later carried on before the New Year beginning the 1st of Pop’. Kin means ’ sun, day, time, so that Yaxkin means ’ new time.

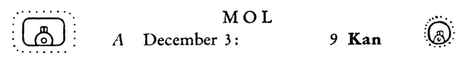

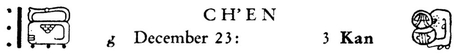

so that Yaxkin means ’ new time. And so even in the later changed arrangement they kept the month Yaxkin for the renewal of all utensils with preparation for the very sacred ceremonial carving of the new images in the following month Mol, and carried through into Ch’en. In the accompanying figures, taken from the Madrid codex, the makers are ceremonially garbed in the habiliments of the gods, and are using what must have been the hardened copper tools elsewhere referred to by Landa, and such as have been actually recovered from the sacred cenote. Then in the months Ch‘en or Yax followed the Oc-na (

And so even in the later changed arrangement they kept the month Yaxkin for the renewal of all utensils with preparation for the very sacred ceremonial carving of the new images in the following month Mol, and carried through into Ch’en. In the accompanying figures, taken from the Madrid codex, the makers are ceremonially garbed in the habiliments of the gods, and are using what must have been the hardened copper tools elsewhere referred to by Landa, and such as have been actually recovered from the sacred cenote. Then in the months Ch‘en or Yax followed the Oc-na ( house-entering ’ ceremony) or renovation of the temples, in honor of the gods of the fields.

house-entering ’ ceremony) or renovation of the temples, in honor of the gods of the fields.

In Landa’s time the l6th of Xul fell on Nov. 8th, beginning Nov. 13th, and Mol ending just at the winter solstice, Dec. 22nd. Owing to our ignorance still as to just how the natural seasons and the months were kept adjusted without our quadrennial leap year method, we have not yet solved the question of the varying New Year dates found through all Middle America; but it is most interesting that this Xul-Yaxkin incidence should be tied in so closely with Quetzalcóatl,in whom we have the most tangled problem in the whole field. Nevertheless, while such specific seasonal ceremonies as planting, harvesting, hunting, etc., must somehow have been kept lined up to their regular month associations, still such a purely historical religious ceremony as this could remain fixed in the months once allotted, regardless of seasonal questions.

What we can say with certainty is that, some thousand years before Landa wrote, the Mayas knew that 1507 true solar years of 365.2422 days equalled 1508  vague ’ years of 365 days; so that New Year’s or any other fixed date would keep falling behind not quite a quarter day every year, to come back in place again only after 1507 revolutions. So that we have here a case where clearly ‘New Year’ ceremonies were celebrated far out of their current place at Landa’s time, and in a secondary

vague ’ years of 365 days; so that New Year’s or any other fixed date would keep falling behind not quite a quarter day every year, to come back in place again only after 1507 revolutions. So that we have here a case where clearly ‘New Year’ ceremonies were celebrated far out of their current place at Landa’s time, and in a secondary  survival ’ form, attached to the transitory presence of Quetzalcóatlin Yucatan (according to the traditions), while the greater and fuller sin-cleansing five-day ceremonies fell in July.

survival ’ form, attached to the transitory presence of Quetzalcóatlin Yucatan (according to the traditions), while the greater and fuller sin-cleansing five-day ceremonies fell in July.

Immediately on the following day the fishermen celebrated their festival in the same order as the others, except that what was anointed was the fishing tackle, and they did not pierce the ears but tore them on the sides; they danced a dance called chohom, and when all this was done they blessed a tall thick tree trunk and set it up erect. After this festival had been celebrated in the towns, it was the custom for the chiefs to go with many of the people to the coast, where they had great fishing and sport, having taken with them a great quantity of drag-nets, hooks and other fishing equipment. The gods who were the patrons of this festival were: Ahkakne-xoi, Ahpua, Ahcitz-amalcum .

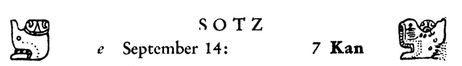

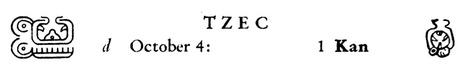

In the month Sotz the proprietors of the bee-hives prepared themselves to celebrate their festival in Tzec, and although the chief preparation here was fasting, there was no obligation save on the priest and the officers who assisted therein, and it was voluntary on the part of the rest.

When the day of the festival had come, they all gathered in the appointed house, and did as in the others, except that there was no drawing of blood, since the patrons were the Bacabs, and especially Hobnil. They made many offerings, and especially to the four chacs they gave four platters with balls of incense in the middle of each, and painted on the rims with figures of honey, to bring abundance of which was the purpose of the ceremony. They ended it with wine as usual, in plenty, the hive owners giving honey for it in abundance.

In the twelfth chapter (Sec. VI) was related the departure of Kukulcán from Yucatan, after which some of the Indians said he had departed to heaven with the gods, wherefore they regarded him as a god and appointed a time when they should celebrate a festival for him as such; this the whole country did until the destruction of Mayapán. After that destruction only the province of Maní kept this up, while the other provinces in recognition of what they owed to Kukulcán made presents, one each year, turn and turn about, of four or sometimes five magnificent banners of feathers, sent to Mani; with which they kept this festival in that manner, and not in the former ways.

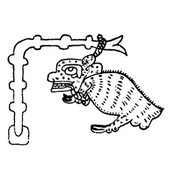

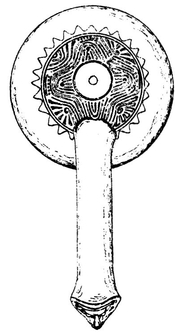

INCENSE BURNER

On the 16th of Xul all the chiefs and priests assembled at Mani, and with them a great multitude from the towns, all of them after preparing themselves by their fasts and abstinences. On the evening of that day they set out in a great procession, with many comedians, from the house of the chief where they had gathered, and marched slowly to the temple of Kukulcán, all duly decorated. On arriving, and offering their prayers, they set the banners on the top of the temple, and below in the court set each of them his idols on leaves of trees brought for this purpose; then making the new fire they began to burn their incense at many points, and to make offerings of viands cooked without salt or pepper, and drinks made from their beans and calabash seeds. There the chiefs and those who had fasted stayed for five days and nights, always burning copal and making their offerings, without returning to their homes, but continuing in prayers and certain sacred dances. Until the first day of Yaxkin these comedians frequented the principal houses, giving their plays and receiving the presents bestowed on them, and then taking all to the temple. Finally, when the five days were passed, they divided the gifts among the chiefs, priests and dancers, collected the banners and idols, returning them to the house of the chief, and thence each one to his home. They said and believed that Kukulcán descended on the last of those days from heaven and received their sacrifices, penances and offerings. This festival they called Chicc-kaban.31

In this month of Yaxkin they began to get ready, as usual, for the general festival they would celebrate in Mol, on the day appointed by the priest for all the gods; they called it Olob-sab-kamyax. After they were gathered in the temple and the same ceremonies and incense burning as in the previous festivals had been gone through with, they anointed with the blue pitch all the instruments of all the various occupations, from that of the priest to the spindles of the women, and even the posts of their houses. For this festival they assembled all the boys and girls, and in place of the painting and the ceremonies they gave to each nine little blows on the knuckles of their hands, outside; for the girls this was done by an old woman, vestured in a robe of feathers, who brought them there; from this she was called Ixmol, meaning the bringer together. These blows they gave them that they might grow up expert craftsmen in their fathers’ and mothers’ occupations. The conclusion was a fine drinking affair, with eating of the offerings, except that we must not believe that the devout old woman was allowed to become so drunk as to lose the feathers of her robe on the road.

In this month the bee-keepers held another festival like they did in the month Tzec, to the end that the gods might provide flowers for the bees.

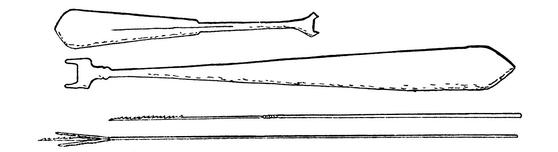

One of the most arduous and difficult things these poor people had to do was the making of images of wood, which they called the gods. Thus they had a particular month designated for this work, and this was the month Mol, or some other if the priest said it was right. Those then who wished to make them first consulted the priest, and after taking his counsel went to the artisans; they say that the artisans always excused themselves, believing that either they or some one of their household would die or would suffer heart attacks or strokes; when however they had accepted, the chacs whom they had chosen to serve in the matter, together with the priest and the artisan, began their fasts. While they were fasting, he who was to have the idols went himself or else sent to the woods for the material, which was always cedar. When the wood arrived they built a small fenced-in hut of thatch, in which they put the wood and a large urn into which to put the idols, and to keep them covered up while they were working. They put incense to be burned to the four deities called the Acantuns, which they brought and placed at the four cardinal points. They also brought the instruments with which to scarify themselves or draw blood from their ears; and also the tools for carving their black gods. When all these were ready in the hut, the priest, the chacs and the artisan shut themselves in the hut, and they began their making the gods, from time to time cutting their ears and anointing the statues herewith, and burning the incense. Thus they worked until they were finished, their families bringing to them their food and needs; during the period they were not to consort with their wives, even in thought; nor could any one enter that place where they worked.

They worked in much reverence and fear, as they say, making the gods. When they were finished and the idols perfected, the owner made them the finest present he was able, of birds, game and their money, to pay for the labor of those who had made them. Then they removed them from the hut and set them in another enclosure of branches prepared for them in the court, where the priest blessed them with great solemnity, and an abundance of devout prayers; but first the priest and the artisans removed the soot with which they had covered themselves during their fasting. Then having exorcised the evil one and burned the sanctified incense, they put the images wrapped in a cloth in a chest and delivered them to their owner, who very devotedly received them. Afterwards the good priest preached a little on the excellence of the artisans’ profession, or making new images of the gods, and on the ills that would have attended them had they not been faithful to the precepts of abstinence and fasting. After that they ate much and drank more.

In whichever of the months Ch‘en or Yax were designated by the priest, and on the day set by him, they celebrated a festival they called Oc-na, meaning the  renovation of the temple,’ in honor of the Chacs, regarded as the gods of the maize fields. In this festival they consulted the predictions of the Bacabs, as we have told at more length in chapters 111 to 116 (Secs. xxxv to XXXVIII), and in conformity with the order there given. Each year they celebrated this festival and renewed the idols of terra cotta, and their braziers, since it was the custom for each idol to have his own little brazier for burning his incense; and if it was necessary they built a new house, or repaired the old one, placing on the wall the record of these things, with their characters.

renovation of the temple,’ in honor of the Chacs, regarded as the gods of the maize fields. In this festival they consulted the predictions of the Bacabs, as we have told at more length in chapters 111 to 116 (Secs. xxxv to XXXVIII), and in conformity with the order there given. Each year they celebrated this festival and renewed the idols of terra cotta, and their braziers, since it was the custom for each idol to have his own little brazier for burning his incense; and if it was necessary they built a new house, or repaired the old one, placing on the wall the record of these things, with their characters.

A: January 29: 1 Imix. Here begins the calendar of the Indians, saying in their language, Hun Imix.*

The hunters, who had celebrated one festival in the month Sip, now celebrated another in the month Sac, on a day set by the priest, doing this to appease the anger of the gods against them and their fields because of the blood they shed in their hunting; for they regarded with abhorrence any shedding of blood except in their sacrifices. For this reason, whenever they went to the hunt, they invoked the god and burned incense to him; and if possible later they anointed the faces with blood from the heart of the game.

f: February 17: 7 Ahau. On whatever day of the year 7 Ahau fell they celebrated a very great festival with incense and offerings, and restrained drinking; and since this was a movable feast it was in the care of the priests to publish it in sufficient time ahead, that they might fast in due manner.

On some one of the days of this month Mac the oldest people celebrated a festival to the Chacs, the gods of sustenance, and Itzamná.One or two days ahead of this they performed the following ceremony, which they called tuppi-kak (‘fire-quenching’). They hunted for as many animals and creatures of the fields as they could, and as there were in the country. With these they gathered in the temple court, where the chacs and the priest placed themselves in the corners to exorcise the evil spirit according to custom, and each with a jar of water, as brought there to him. In the middle they placed, set up erect, a large bundle of dry sticks, tied together; then first burning the incense in the braziers they set fire to the sticks, and as they burned they drew out the hearts of the birds and animals, liberally, and threw them into the flames. If they had been unable to get any of the larger animals, such as tigers, lions or caimans, they made hearts out of incense instead. If they had killed any, they brought their hearts for the fire. Then when the hearts were all consumed, the chacs extinguished the fire with their jars of water. This and the coming festival were to obtain the needed rains for their maize crops in the ensuing year; they thereupon celebrated the fiesta.

This was done in a different manner from the others, since for this they did not fast, except that the provider of the festival did his fast. When the time arrived, all the townsfolk, the priest and the officials assembled in the temple court, where they had a pyramid of stones, with stairways, all clean and dressed with green branches. The priest then gave the prepared incense to the one providing, and he burned it in the brazier, whereby they said the evil spirit was exorcised. This being done with their accustomed reverence, they spread the lower step of the pyramid with mud from the well, and the other steps with blue pitch.

They used much incense and invoked Itzamná and the Chacs with prayers and rituals, and made their offerings. When this had been done they took their comfort in eating and drinking what had been offered, confident that their service and invocations would bring a prosperous new year.

During the month Muan the owners of cacao plantations made a festival for the gods Ekchuah, Chac and Hobnil, who were their protectors. To do this they went to the property of one of them, where they sacrificed a dog spotted with the colors of the cacao, burned incense to their idols, and offered up iguanas of the blue sort, with certain bird’s feathers, and other game; then they gave to each one of the officers a branch of the cacao fruit. After the sacrifice and the prayers they ate the gifts and drank, but (as they tell) no more than three draughts of the wine, no more than this having been brought. After this they went to the house of him who had provided the fiesta, for various diversions.

In this month of Pax they celebrated a festival called Pacum-chac, for which the priests and chiefs of the smaller villages gathered at the larger towns, where they all watched for five nights in the temple of Cit-chac-coh, with prayers, offerings and incense, as has been related of the festival to Kukulcán in the month Xul, in November. Before these days were passed, they all went to the house of their war general, the Nacon (of whom we spoke in chapter 101) (See. xxx), and with great pomp they conducted him to the temple, offering incense to him as to an idol, and then seating and incensing him as if he were a god; there he and they stayed through the five days, during which they ate and drank of the gifts that had been brought to the temple, and performed a great dance in the style of war manoeuvers, called in their language Holcan-okot, or the dance of the warriors. After these five days they went on to the fiesta which, since it was for matters of war and victory over their enemies, was very solemn.

First they went through the ceremony and sacrifices of the Fire, as I told under the month Mac; then in the usual manner they drove out the evil spirit with great solemnity. After this came prayers and the offering of gifts and incense, and while they were doing this the chiefs and those who had before assisted in this, again carried the Nacon on their shoulders around the temple, with incense. When they returned with him, the priests sacrificed a dog, drew out its heart and presented it between two platters to the demon, while the chacs each broke large jars full of liquor, and with this ended the festival. When it was over they ate and drank the gifts that had been brought, and then reconducted the Nacon to his home, with great ceremony, but without perfumes.

There they held a great fiesta in which the lords and the priests and leading men drank to intoxication, and the rest of the people went to their towns; but the Nacon did not join in the intoxication. On the next day, when the effects of the wine had passed off, all the lords and priests of the towns who had remained at the chief’s house and taken part in this last act, received from him a great quantity of incense prepared for the purpose, which had been blessed by the holy priests. He then joined them and gave a long discourse in which with much emphasis he enjoined on them the festivals they should, in their own towns, celebrate for the gods, that the coming year might yield many things for their support. After the address, all departed with much expression of affection and noise, each going to his town and home.

There they busied themselves with the fiestas, which according to the circumstances, continued until the month Pop’, and which they called Sabacil-than, and performed as follows. They looked through the town for the richest men able to afford the costs of the fiesta, and set a day, to provide the most entertainment during the remaining three months before the new year. They gathered at the house of the feast maker, went through the ceremonies of driving away the evil spirit, burning copal, with offerings and dances, and making themselves such wine kegs, and such was the excess in these fiestas for these three months that it was painful to see them; for they went about scratched and bruised and red-eyed with the drink, all for this love of the wine for which they had destroyed themselves.

It has been told in the preceding chapters how the Indians began their year following these  nameless days,’ preparing there as with vigils for the celebration of the New Year festival; in the same interval they celebrated the festival of the Uvayeyab demon, for which they left their houses, which otherwise they left as little as possible; they offered besides gifts for the general festival, and counters for their gods and those of the temples. These counters they thus offered they never took for their own use, nor anything that was given to the god, but with them bought incense for burning. During these days they neither combed nor washed, nor otherwise cared for themselves, neither men nor women; neither did they perform any servile or heavy work, fearing lest evil fall on them.

nameless days,’ preparing there as with vigils for the celebration of the New Year festival; in the same interval they celebrated the festival of the Uvayeyab demon, for which they left their houses, which otherwise they left as little as possible; they offered besides gifts for the general festival, and counters for their gods and those of the temples. These counters they thus offered they never took for their own use, nor anything that was given to the god, but with them bought incense for burning. During these days they neither combed nor washed, nor otherwise cared for themselves, neither men nor women; neither did they perform any servile or heavy work, fearing lest evil fall on them.

SEC. XLI. CYCLE OF THE MAYAS. THEIR WRITINGS.

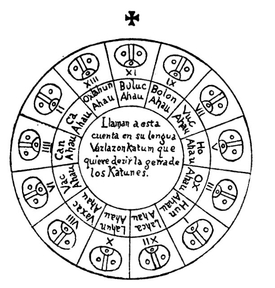

Not only did the Indians have a count for the year and months, as has been before set out, but they also had a certain method of counting time and their matters by ages, which they counted by 20-year periods, counting thirteen twenties, with one of the twenty signs in their months, which they call Ahau, not in order, but going backwards as appears in the following circular design. In their language they call these periods katuns, with these making a calculation of ages that is marvelous; thus it was easy for the old man of whom I spoke in the first chapter to recall events which he said had taken place 300 years before. Had I not known of this calculation I should not have believed it possible to recall after such a period.32

As to who it was that arranged this count of katuns, if it was the evil one it was so done as to serve in his honor; if it was a man, he must have been a great idolater, for to these katuns he added all the deceptions, auguries and impostures by which these people walked in their misery, completely blinded in error. Thus this was the science to which they gave most credit, held in highest regard, and of which not even all the priests knew the whole. The way they had for counting their affairs by this count, was that they had in the temple two idols dedicated to two of these characters. To the first, beginning the count with the cross above the circular design, they offered worship, with services and sacrifices to secure freedom from ills during the twenty years; but after ten years of the first twenty had passed, they did no more than burn incense and do it reverence. When the twenty years of the first had passed, they began to follow the fates of the second, making their sacrifices; and then having taken away that first idol, they set up another for veneration during the next ten years.

Verbi gratia. The Indians say that the Spaniards finally reached the city of Mérida in the year of Our Lord’s birth 1541, which was exactly at the first year of the era of Buluc (11) Ahau, which is in that block where the cross stands; also that they arrived in the month Pop’, which is the first month of their year. If the Spaniards had not arrived, they would have worshipped the image of Buluc Ahau until the year ’51, that is for ten years, and then would have set up another idol for Bolon (9) Ahau up to the year’ 61, when they would remove it from the temple and replace it with the idol for Vuc Ahau, then following the predictions of Bolon Ahau for another ten years, thus doing with all in their turn. Thus they venerated each katun for twenty years, and during ten years they governed themselves by their superstitions and deceits, all of which were so many and such as to hold in error these simple people, that one would have to marvel over it who did not know the things of Nature and the experience the devil possesses in dealing with them.

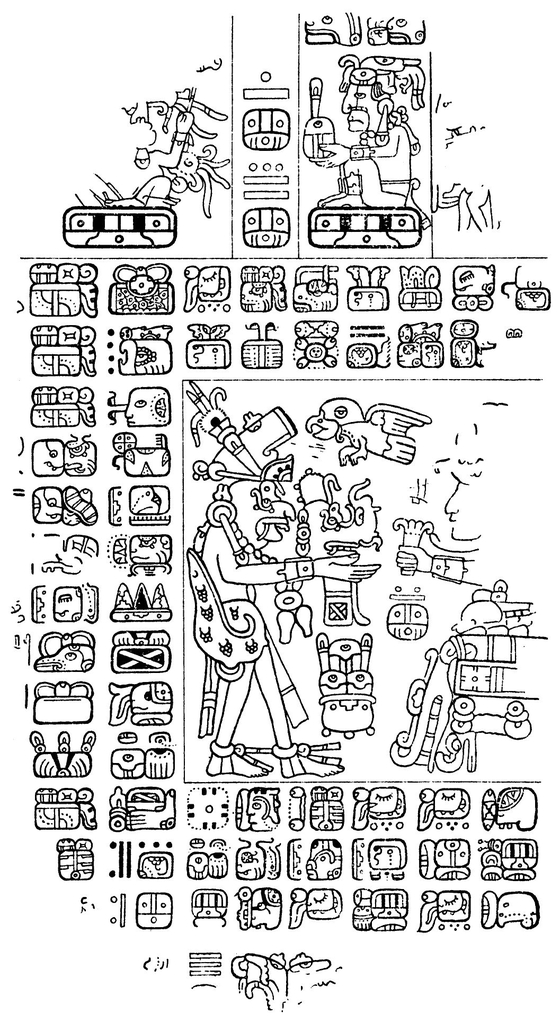

These people also used certain characters or letters, with which they wrote in their books about the antiquities and their sciences; with these, and with figures, and certain signs in the figures, they understood their matters, made them known, and taught them. We found a great number of books in these letters, and since they contained nothing but superstitions and falsehoods of the devil we burned them all, which they took most grievously, and which gave them great pain.

Of their letters we give here an a, b, c, their cumbersomeness not permitting more, because for all the aspirations of the letters they use one character, and then for uniting the parts another, going on in this way ad infinitum, as in the following example. Le means a lasso, and to hunt with one; to write it with their letters, they wrote them with three, at the aspiration of the 1 the vowel e, put before it; in this they are not at fault, although they use the e if they wish to do so for definiteness. Example: e l e lé; afterwards they put the syllable joined:

Há means water; because the sound of the letter aitch is composed of a, h, before it, they put it at the beginning with a, and a ha at the end in this fashion:

They also wrote in syllables, but in one and the other style: I only put it here in order to give a complete account of the matters of this people. Ma in kati means ‘I do not wish,’ and they write it in syllables in this manner:

Here begins their a, b, c:

The letters that do not appear are wanting in this language; and they have others in addition to ours, for other things where they are needed. But they no longer use any of the characters, especially the young people who have e learned ours.

PARIS CODEX, PAGE 6

SEC. XLII. MULTITUDE OF BUILDINGS IN YUCATAN. THOSE OF IZAMAL, OF MERIDA, AND OF CHICHEN ITZA.

If the number, grandeur and beauty of its buildings were to count toward the attainment of renown and reputation in the same way as gold, silver and riches have done for other parts of the Indies, Yucatan would have become as famous as Peru and New Spain have become, so many, in so many places, and so well built of stone are they, it is a marvel; the buildings themselves, and their number, are the most outstanding thing that has been discovered in the Indies.

Because this country, a good land as it is, is not today as it seems to have been in the time of prosperity when so many great edifices were erected with no native supply of metals for the work, I shall put here the reasons I have heard given by those who have seen these works. These are that they must have been the subjects of princes who wished to keep them occupied and therefore set them to these tasks; or else that they were so devoted to their idols that these temples were built by community work; or else that since the settlements were changed and thus new temples and sanctuaries were needed, as well as houses for the use of their lords, these being always constructed of wood and thatch; or again, the reason lay in the ample supply in the land of stone, lime and a certain white earth excellent for building use, so that it would seem an imaginary tale, save to those who have seen them.

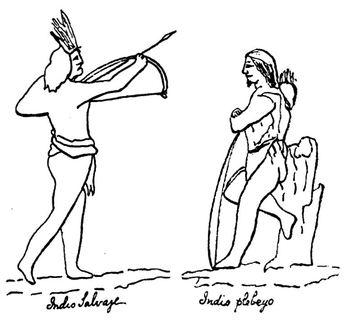

It may be that this country holds a secret that up to the present has not been revealed, or which the natives of today cannot tell. To say that other nations compelled these people to such building, is not the answer, because of the evidences that they were built by the Indians themselves; this is bared to view in one out of the many and great buildings that exist, Whereon the walls of the bastions there still remain figures of men naked save for the long girdles over the loins called in their language ex, together with other apparel the Indians of today still wear, worked in very hard cement.

While I was living there, in a building we were demolishing there was found a large jar with three handles, adorned with figures applied on the outside; within, among the ashes of a cremated body, we found three counters of fine stone, such as the Indians today use as money, all showing the people were Indians. It is clear that if such they were, they were of higher grade than those of today, and greater in bodies and strength. This shows more clearly here in Izamal than elsewhere, there being here, as I say, today on the bastions figures in semi-relief, made of cement, and of men of great height. The same is true of the extremities of the arms and legs of the man whose ashes we found in the jar I have referred to; these also were very thick, and their burning a marvel. We see the same thing on the steps of the buildings, here only in Izamal and Mérida, of a good two palms in height.

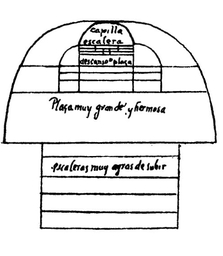

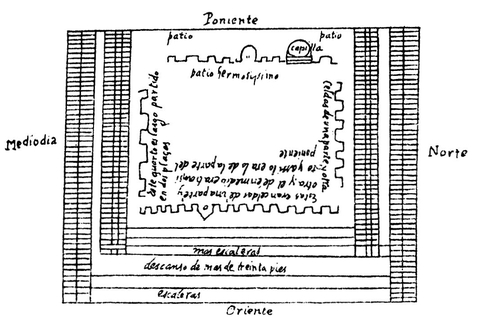

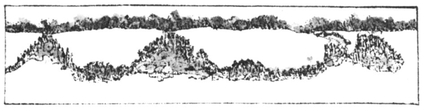

Here in Izamal is a building, among the others, of a startling height and beauty, as is seen in this sketch and its explanation. 33 It has twenty steps, each more than two palms in height and in breadth, and being over a hundred feet in length. These steps are of very large carved stones, although now much worn and damaged by time and water. Around them, as is shown by the curved line, is a very strong dressed stone wall; at one and a half times the height of a man there is a cornice of beautiful stone going all the way around, from which the work continues to the height of the first stairway, and the plaza in the sketch.

From this plaza there rises another stairway like the first, but not so long nor with so many steps, again with an encircling wall. Above these steps there is another fine small platform, on which, close to the surrounding wall, is a very high mound with steps facing the south like the other great stairs, and on top of this a beautiful finely worked chapel of stone. I went to the top of this chapel, and Yucatan being a flat country I could see as far as the eye could reach, an amazing distance, as far as the sea. There were eleven or twelve of these buildings at Izamal, this being the largest, and all near together. There is no memory of the builders, who seem to have been the first inhabitants. It is eight leagues from the sea, in a beautiful site, good country and district, and so in 1549, with some importunity, we had the Indians build a house for St. Anthony on one of these structures. There and all around great benefit has come in its Christianity; so that two good communities have been established in this place, distinct from each other.

The second of the chief ancient structures, such that there is no record of their builders, are those at Tiho, thirteen leagues from those at Izamal, and like them eight leagues from the sea; and there are traces of there having been a fine paved road from one to the other. The Spaniards established a city here, and called it Mérida, from the strangeness and grandeur of the buildings; the chief one of which I shall show here as well as I can, as I did that at Izamal, that it may be seen what it was like.

This is the sketch I have drawn; to understand it, it must be noted that it is a squared site of great size, more than two runs of a horse. 34 On the east front the stairway begins at the ground level, with seven steps as high as those at Izamal; on the other three sides, the south, west and north, there runs a very broad strong wall. On top of this first mass, all squared and of dry stone, and flat, there starts again on the east side another stairway, 28 to 30 feet further in than the other stairway, as I judge, and with steps equally large. On the north and south, but not on the west, it is again set back the same distance, with two strong walls reaching the height of the stairway, and continuing until they meet those of the west face, forming a great mass of dry stone in the center, built by hand, of an amazing height and greatness.

On the East, stairway, platform of more than 30 feet; then more stairs. At the South, a long apartment, divided; at the North, another, same. At the West another range broken by an arcade, and with a chapel, and patios in front and behind. In the center a great patio, between the two ranges, each made up of rooms, broken by arcades.

On the level top are buildings in the following manner: six feet back of the stairway is a long range not reaching to the ends, of very fine stonework, made up of cells on each side, twelve feet long by eight wide; the doors of these have no sign of facings or hinges for closing, but are flat and of stone elaborately worked, the whole marvelously built, and the tops of the doorways formed of single large stones. In the middle is a passageway like the arch of a bridge; above the doors of the cells there projected a relief of worked stone the whole length of the structure. Above this was a line of small pillars, half inset in the wall with the outer part rounded, and reaching to the level of the cell roofs. Above these there was another relief extending the whole length of the range; and then came the terrace, finished with a very hard stucco made with the water from the bark of a certain tree.

On the north was another range with cells, the same as the above, but the whole only half the length. On the west was another line of the cells, pierced at the fourth or fifth by an arcade going clear through the whole, like the one in the east front; then a round, rather tall building; then another arcade, and the rest cells like the others. 35 This range crosses the whole court not quite in the center, thus making two courts, one to the back at the west, the other on the east, surrounded by four ranges as described. The last of these ranges however, to the south, is quite different. This consists of two sections, arched along the front like the rest, the front being a corridor of very thick pillars topped by very beautifully worked single stones. In the middle is a wall against which comes the arch of the two rooms, with two passageways from one to the other; the whole is thus enclosed above and serves as a retreat.

About two good stone-throws distant from this edifice is another very high and beautiful court, containing three finely ornamented pyramids, on top of them chapels, arched in the fashion they were used to employ. Quite a distance away was a pyramid, so large and beautiful that even after it had been used to build a large part of the city they founded around it, I cannot say that it shows any signs of coming to an end.

The first of the above structures, with the four ranges, was given to us by the admiral Montejo, all covered with heavy trees; we cleared it, and there built us a proper monastery all of stone, and a fine church which we called after the Mother of God. There was so much stone that after leaving the southern range, and part of the others, we gave much stone to the Spaniards for their houses, particularly for their doors and windows; such was the abundance.

The buildings at Tikoch are not so many nor so sumptuous as many of these others, although they were good and noteworthy; I only mention them here on account of the great population there must have been, as I have before had to relate; thus I leave this here. These buildings are three leagues from Izamal toward the east, and seven leagues from Chichén Itzá.

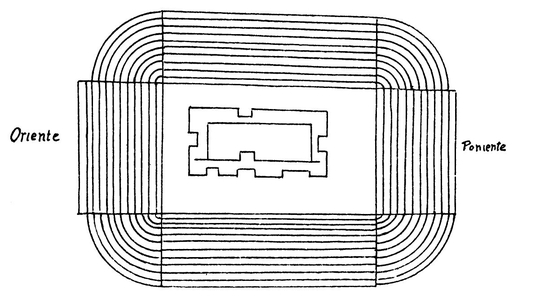

Chichén Itzá, then, is a fine site, ten leagues from Izamal and eleven from Valladolid. Here as the old men of the Indians say, there reigned three lords, brothers who (as they recall to have been told them by their ancestors) came from the land to the west, and gathered in these places a great settlement of communities and people whom they ruled for some years in great peace, and with justice. They greatly honored their god, and thus erected many magnificent buildings; especially one, the greatest, whose design I shall give here as I sketched it by standing on it, the better to explain it.

They say that these lords lived as celibates and with great propriety, being highly esteemed and obeyed by all while they so lived. In the course of time one of them failed, so that he died; although the Indians say that he went away by the port of Bacalar, out of the country. However that was, his absence resulted in such a lowering among those who ruled after him that partisan dissensions entered the realm; they lived dissolutely and without restraint, to such a degree that the people came to hate them so greatly that they killed them, overthrew the regime, and abandoned the site. The buildings and the sites, both beautiful, and only ten leagues from the sea, with fertile fields and districts all about, were deserted. The following is the plan of the principal edifice:

This structure has four stairways looking to the four directions of the world, and 33 feet wide, with 91 steps to each that are killing to climb. The steps have the same rise and width as we give to ours. Each stairway has two low ramps level with the steps, two feet broad and of fine stonework, like all the rest of the structure. The structure is without corners, because starting from the base it narrows in, as shown, away from the ramps of the stairs, with round blocks rising by stages in a very graceful manner.

When I saw it there was at the foot of each side of the stairways the fierce mouth of a serpent, curiously worked from a single stone. When the stairways thus reach the summit, there is a small flat top, on which was a building with four rooms, each having a door in the middle, and arched above. The one at the north is by itself, with a corridor of thick pillars. In the center is a sort of interior room, following the lines of the outside of the building, with a door opening into the corridor at the north, closed in the top by wooden beams; this served for burning the incense. At the entrance of this doorway or of the corridor, there is a sort of arms sculptured on a stone, which I could not well understand.

Around this structure there were, and still today are, many others, well built and large; all the ground about them was paved, traces being still visible, so strong was the cement of which they were made. In front of the north stairway, at some distance, there were two small theatres of masonry, with four staircases, and paved on top with stones, on which they presented plays and comedies to divert the people.

From the court in front of these theatres there goes a beautiful broad paved way, leading to a well two stone-throws across. Into this well they were and still are accustomed to throw men alive as a sacrifice to the gods in times of drought; they held that they did not die, even though they were not seen again. They also threw in many other offerings of precious stones and things they valued greatly; so if there were gold in this country, this well would have received most of it, so devout were the Indians in this.

This well is seven long fathoms deep to the surface of the water, more than a hundred feet wide, round, of natural rock marvelously smooth down to the water. The water looks green, caused as I think by the trees that surround it; it is very deep. At the top, near the mouth, is a small building where I found idols made in honor of all the principal buildings in the land, like the Pantheon at Rome. I do not know whether this is an ancient invention, or one of the modern ones, that in coming with offerings to the well, they might come into the presence of their idols. I found sculptured lions, vases and other things, so that I do not understand how anyone can say that these people had no tools. I also found two immense statues of men, carved of a single stone, nude save for the waist-covering the Indians use. The heads were peculiar, with rings such as the Indians use in their ears, and a collar that rested in a depression made in the chest to receive it, and wherewith the figure was complete.

SEC. XLIII. FOR WHAT OTHER THINGS THE INDIANS MADE SACRIFICES.

The calendar festivals of this people that have been described above, show us what and how many they were, and wherefor and how they were celebrated. But because their festivals were only to secure the goodwill or favor of their gods, or else holding them angry, they made neither more nor bloodier ones. They believed them angry whenever they were molested by pestilences, dissensions, or droughts or the like ills, and then they did not undertake to appease the demons by sacrificing animals, nor making offerings only of their food and drink, or their own blood and self-afflictions of vigils, fasts and continence; instead, forgetful of all natural piety and all law of reason they made sacrifices of human beings as easily as they did of birds, and as often as their accursed priests or the chilánes said it was necessary, or as it was the whim or will of their chiefs. And since there is not here the great population there is in Mexico, nor were they after the fall of Mayapán ruled by one head but by many, there were no such mass killings of men; nevertheless they still died miserably, since each town had the authority to sacrifice whomever the priests, or the chilán, or the chief saw fit; and to do this they had in their temples their public places as if it were the one thing of most importance in the world for the preservation of the state. In addition to this slaughter in their towns, they had those accursed sanctuaries of Chichén Itzá and Cozumel whither they sent an infinite number of poor creatures for sacrifice, one thrown from a height, another to have his heart torn out. From all such miseries may the merciful Lord see fit to free us forever, He who saw fit to sacrifice himself to the Father, on the cross for all men.

O Lord my God, light, being and life of my soul, holy guide and safe road for my customs, consolation of my griefs, inner joy of my sadnesses, refreshment and rest of my toils: Why, O Lord, dost thou command me tasks that I cannot perform, rather than rest? What dost thou lay on me that I cannot carry through? Lord, dost thou not know the measure of my cup and the extent of my members and the quality of my forces? Dost thou perchance fail me, Lord, in my labors? Art thou not the loving Father of whom the holy prophet spoke in the psalm, I will be with him in tribulation and labors, and I will liberate him and glorify him? Lord, if thou art, and thou art He of whom the prophet spoke when full of thy holy spirit, that makest of thy command a burden, and thus it is, Lord, that those who have not enjoyed the sweetness of thy service and the performance of thy precepts, find a burden in them; but Lord, it is a pretended burden, a burden feared, a burden to the pusillanimous, and they fear it who never put the hand to the plow to finish; but those who give themselves to thy services find them sweet, they seek after the odor of their unctions,36 their sweetness refreshes them at every step; many more pleasures do they find daily that the others cannot know, as in the other kingdom of Saba.