God’s Kingdom? I thought they called it that because only God would want the place.

—CHARLES KINNESON, EDITOR,

The Kingdom County Monitor

Jim pulled out of the dooryard of the farm that wasn’t in the pale light before the sun. It was Labor Day in God’s Kingdom, and he was on his way over the mountains to the university.

The wild asters and goldenrod in the meadow along the river, where four years ago he’d encountered Gaëtan Dubois and his parents, were just acquiring color in the dawn. The river was invisible in its own fog, but the swamp maples along its banks were already showing sprays of red. Soon the brook trout would don their matrimonial attire, in preparation for their annual fall spawning ritual.

For Jim it had been a busy, lonely summer. To take his mind off Frannie, he’d thrown himself into his work at the Monitor. In addition to the constant round of selectmen’s and school board meetings, court arraignments, fairs and old-home days, car wrecks, and ball games on the common—“Outlaws Remain Undefeated with 10-1 Win over Pond in the Sky”—not to mention the appearance on the village green of a snapping turtle as big around as a washtub with “Charles Kinneson 1765” carved into its shell (Jim detected his brother Charlie’s handiwork in the date and signature), there had been several unexpected developments to cover over the short northern summer.

In late June, the Common and its longtime enemy, Kingdom Landing, had voted to build a new consolidated high school midway between the rival villages. No one in God’s Kingdom had ever imagined that such a thing could happen. Two weeks later, all passenger service on the Boston and Montreal Line running through the Common was terminated. Jim could see the time coming when rail freight service would end as well. There was talk of the Eisenhower interstate system reaching the Kingdom, and a ski resort on Jay Peak.

One morning in early August, Mr. Arthur Anderson keeled over at his desk at the factory. His sons, who ran the firm’s sister plants in Michigan and Pennsylvania, shut down the mill on the day of their father’s funeral. It never reopened. “Closed,” the sign on the roof read.

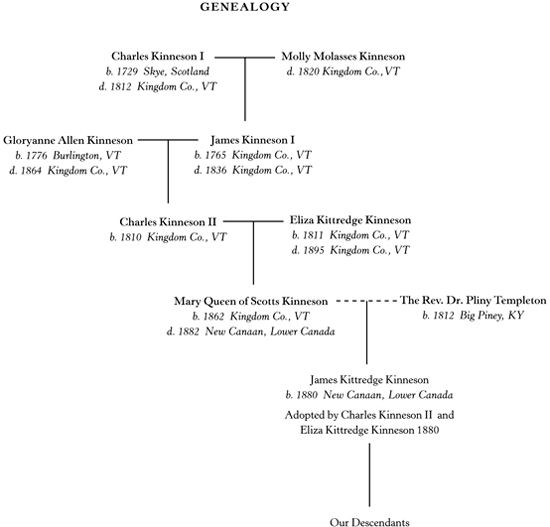

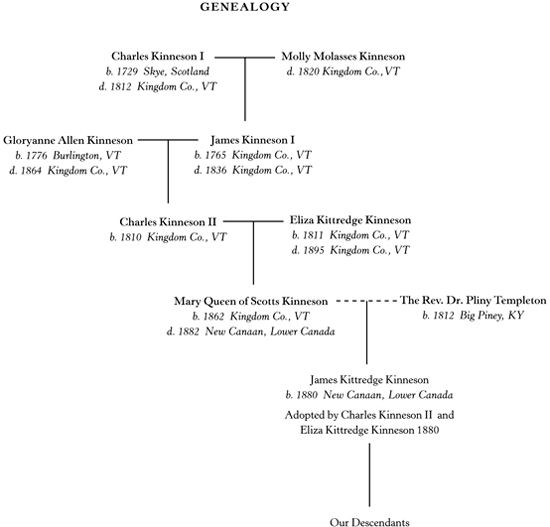

Pliny Templeton had written in his great book that in the Kingdom, all history was Kinneson family history. Over the summer Jim had done a series of articles for the Monitor on his ancestors. He’d written about the massacre of the Abenaki Indians by his great-great-great grandfather Charles Kinneson I, and the defeat and death of Charles I’s son, the secessionist James, at the second-longest covered bridge in the world in 1836. Another article chronicled Charles II’s rerouting of the outlet of Lake Kingdom. Yet another described the burning of New Canaan and three million acres of border country by the Ku Klux Klan.

Jim’s favorite piece was the three-part biography he’d written of Pliny Templeton himself. A condensed version had been syndicated by the Associated Press. Jim hoped someday to write a novel about Pliny.

He crossed the red iron bridge and came into the Common on the county road. As he headed south between the east side of the village green and the Academy, he noticed a light in the headmaster’s office. On impulse, he pulled into one of the diagonal parking slots in front of the playground. As Jim walked up the granite steps of the school, it seemed just yesterday that he’d first seen Frannie, standing on the bottom step in her dress of many colors and narrowing her eyes at the jump-rope girls.

The front door was propped open with a cardboard box containing several framed photographs and plaques that Jim recognized. Down the hallway, in his former office, Prof was cleaning out his desk. “Hey, there, Jim,” he said. “I should have done this months ago. You on your way to future fame and fortune this a of m?”

Jim grinned at his old friend. “I’m on my way somewhere. You mind if I slip upstairs and say so long to Dr. T?”

“I don’t mind and it wouldn’t matter if I did,” Prof said. “Congrats again on your scholarship. Hit ’em hard, son.”

They shook hands and Jim went on down the dim hall and upstairs to the science room. Thanks, Dr. Templeton. Thanks for your school. Later, Jim wasn’t sure whether he’d spoken the words aloud or just thought them.

Jim continued along the upper corridor from the science lab to his favorite room in the Academy. The library smelled excitingly of well-read old books. On the lectern next to the librarian’s desk sat Pliny’s wonder-book. Jim began to page through the manuscript. It occurred to him that he might be doing this to put off his departure from the village.

On some pages Pliny had drawn a line through a sentence or paragraph. Here and there he’d inked in a revision. The old headmaster had even made what he’d evidently deemed an improvement to the legend he’d copied from the sounding board above the pulpit. The first three lines, written in the same jet-black ink as the rest of the manuscript, remained unaltered:

The Board casts the Dominie’s voice on high.

But should that Cleric tell a lie,

The Hand of God lets go.

The last two lines—“The Board descends on the man below. The Dominie dies”—had been struck out, then revised in blue ink, to read:

The Board splits apart on the pulpit below.

There end all lies.

To Jim the revision seemed out of sync with the rest of the legend. “There end all lies” was less momentous than “The Dominie dies.”

“See Genealogy,” Pliny’d written in the margin beside the revised lines. But all that remained of the genealogy at the end of the bound manuscript was a jagged strip of paper where the page had been torn out of the book. Why? Why, for that matter, would “all lies end” if the sounding board were to shatter apart on the pulpit of the church? There was a way to find out.

* * *

In those years in God’s Kingdom, no church door was ever locked. A church was a sanctuary. If a member of the congregation needed to go there to pray, no matter the hour of the day or night, the church needed to be open. If a traveler came through town, even a hobo or a bindle stiff off the railroad, the church door must be unlocked.

The eight-foot stepladder used to dust the woodwork around the tall windows stood on the bottom landing of the belfry, where it was kept when not in use. In the cabinet under the sink of the basement kitchen, Jim located a claw hammer. The ladder and hammer should be all he needed.

A layer of dust coated the top of the sounding board and the carved hand gripping the brass handle. To Jim there was still something deeply disturbing about the Hand of God. He was tempted to smash the thing to bits with his hammer.

Instead, he steadied the wooden box from below with his left hand, wedged the hammer claw under one of the top boards, and began to pry the board upward. The square-headed nails shrieked in protest as they pulled away from the checked pine wood. Jim reached inside the box and felt something smooth. In order to remove it, he had to wrench up another board with the hammer claw.

It was a leather-covered briefcase. Embossed on its side in gold letters were the words “To the Reverend Dr. Pliny Templeton in Commemoration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Kingdom Common Academy.” Over time, the metal hasps of the case had tarnished, but with a little pressure they snapped open. Inside was a sheaf of papers bound together with a slender cord. They appeared to be the same high-quality vellum as Pliny’s manuscript. The elegant, copperplate handwriting was almost certainly the headmaster’s.

Jim climbed down the ladder with the briefcase. For some reason he sat in the same place in the second pew he’d sat in three months ago at graduation. He could feel his heart beating faster as he untied the bow knot in the string. In the early sunshine falling through the east windows of the church, Jim read the following letter, addressed to his grandfather.

Good Friday Eve, 1900

Kingdom Common, Vermont

To: James Kittredge Kinneson

My dear James,

I believe that I may have very little time. I must write quickly. He came at dusk this evening. He will come again tomorrow “before the cock crows thrice.” He told me so.

The all-knowing Common will no doubt suppose that we quarreled over my intention to introduce, of all things, a piano into my school. They will imagine that we fought over a minor point of doctrine. Not so, James. The only doctrine your “Kinneson father,” as I shall refer to him, ever truly subjected himself to was the doctrine of universal freedom and the total and permanent abolition of all slavery everywhere. In this regard, as has been said of him many times, he “out-Browned John Brown.” Yet the great irony, and this you must never forget, is he also has always had only your best interest, and the best interest of your descendants, in mind. He loves you as much as any true father could ever love a child. Where he and I are at variance is whether it is in your best interest to know what I believe I must now tell you, and my dear companion and adoptive brother, your Kinneson father, believes as fervently that I must not.

Might I yet flee? Is there still time? There is. I could flee on the Midnight Special to Boston or the Aurora Borealis to Montreal. I will not be aboard either. I have fled enough, James. First from slavery. Then from Andersonville. And always, since coming here to God’s Kingdom, from my own identity. I flee no more forever.

The hands of the steeple clock have wings. I must make my disclosures without further preamble.

Her name—I mean the one girl born to your branch of the Kinneson family since Charles Kinneson I settled here—was Mary. Mary Queen of Scots Kinneson. She was the daughter of your Kinneson father, Charles II, and his wife, Eliza Kittredge Kinneson, and died in the Great Fire of ’82, five years after you were born.

Now, James, I must tell you that almost from birth, Mary Kinneson was a mystery to everyone. She was much cherished as the first girl in Charles I’s family for many generations, and a very loving child at that. There was no animal, tame or wild, that she did not adore. The birds of the air sometimes flew to her, as they did to St. Francis. As she grew older, it became apparent that she was beloved by small children, whom she would entertain by the hour. She sat for days on end with the sick and elderly and comforted anyone in sorrow. Like you, James, she was a superior student. Yet at heart she was a wilding, with her father’s, your Kinneson father’s, anarchic spirit. It was the injustice in the world that she could not accept. Whereas your Kinneson father devoted his life to opposing slavery, she seemed determined, from an early age, to oppose Him whom she regarded as the architect of all injustice.

She had long red hair and eyes as green as sea glass. She was long of limb, like her father, and well-proportioned, in a womanly way, from her early teens. That, I fear, may have led to her ultimate downfall, and mine. Yet the entire fault for what transpired rests with me, James, not with Mary. I was old enough to be her father. Nay, her grandfather. And I was married. In the eyes of God, and in my own eyes, I was still married to my wife, sold away from me down the river in what now seems like another life.

Why mince words? Suffice it to say that it is far from unheard of for schoolgirls, at an impressionable age, to become infatuated with their teachers, be they men or women, and vice versa. I do not say this in my own defense. I have no defense.

At my invitation, Mary began attending the evening confirmation classes I taught to the youths of my congregation. She who, at sixteen, was already as confirmed in her outspoken atheism as the Pope of Rome in his priest-craft.

On the pretext of correcting her heresies, I catechized her. Oh, Pliny! Self-duped Pliny! You knew precisely what you were doing.

Mary was a gifted artist. This you know. You have seen, many times, her famous mural at the courthouse, The Seven Wonders of God’s Kingdom. In her oils and watercolors she could capture the unique character of a place or a person. I confess to you that I was flattered when she proposed to paint my portrait, to hang in the great front atrium of the Academy.

No doubt the portrait was, and is, an excellent likeness. In it, however, she had laid a subtle emphasis on my wide nose, full lips, and dark coloration. I do not mean to suggest that the painting is in any way a caricature. To the contrary, it honors its subject. But whereas, in my tenure in Kingdom County, I have done all in my power to divert attention from my race, by ignoring it, the painting, The Reverend Dr. Pliny Templeton, Founder of the Kingdom Common Academy, is unmistakably that of a Negro man. What had I expected it to look like? It looked like me.

Meanwhile, at our confirmation classes, she had a hundred questions. How could a wholly good creator fashion a world so full of iniquity? How could this same omnipotent God allow His children to so torment and slaughter one another? To be sure, I had been well schooled at the seminary in all of the stock answers to those conundrums, to which, I fear, there are no humanly understandable answers. I spoke, eloquently enough I suppose, of free will, of paradoxes, of what it is given to us to know and not to know. I spoke and she smiled.

What more can I say? Our “classes” had begun in January. By March she was with child. Soon she began to show. Our ardor only increased. James, I should have married her. I loved her, as much for her fearless mind as for her strange beauty. I believe that, for all her antic ways, she loved me. Why else would she make the portrait in the school lobby far more handsome and noble than he who inspired it?

In desperation, I repaired to my friend and adoptive brother, your Kinneson father. I bared my soul to him. I spared myself nothing. I did everything in my power to exculpate Mary. When I finished my shameful account, Charles regarded me for a moment. I knew that he kept, in his desk drawer, his wartime pistol. I thought he might pull it out and shoot me. I half hoped that he would.

Instead, he gave a harsh laugh. “Hoot, brother,” he said. “I cannot claim to be astonished. True, you of all persons should have known better. Then again, a man’s a man. Leave the matter in my hands. Only pledge me one pledge. Give me your word that you will never tell another what you have just told me. Will you pledge?”

“Aye,” I said. “I give you my word. I pledge never to tell another what I have told you.”

Note this well, James. Sly old Pharisee that I was, I pledged nothing, in our compact, about never writing the truth.

Your Kinneson father—soon enough you will learn why I refer to him as such—then set in motion the machinery of an elaborate scheme. Mary he banished to New Canaan, the community of former slaves that he and I established on the Canadian bank of the Upper Kingdom River. And here a strange story takes a turn stranger still.

Some months before Mary’s baby was born, Charles’s wife, your Kinneson mother, stopped going to church. She no longer came into the Common to market, nor did she call upon, or receive calls from, neighbors. Charles put out word that she was expecting another child. She was, as you know, much younger than him, though by then near the end of her childbearing years. There was a good deal of concern for her. But in due time, and without incident, she brought forth a healthy male child named James Kittredge Kinneson. That, of course, was you. As for Mary, rumors flew. She had left the Kingdom for the art institute in Montreal. She had died in childbirth. In fact, she took up with a stonecutter from New Canaan, a decent young man, by all accounts, who treated her well.

In this way, James, a few years passed. And then, dear God, came Armageddon, Armageddon in the incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan. It was a Sunday evening, when most of the New Canaanites were at vespers worship. The Klansmen barred the church door and burned out the church and the village. So far as Charles and I could tell, Mary and her stonecutter consort perished in the flames, which quickly ignited the nearby woods and, as you know, eventually destroyed three million acres of borderland forest, not to mention several entire towns and scores of farmsteads in Vermont, New Hampshire, Quebec, and Maine.

James, I must cut this missive short. I plan to leave it, with the genealogy, inside the sounding board at the church, and to amend, in my History, the legend carved onto that board, as a guidepost that I hope will lead you to their discovery. I know of no other stratagem to put these documents in your hands. Were I to come tonight to your home, the home of your Kinneson father, I am certain he would—but there I will not venture. I will add only that had I married Mary, had I not been a part of Charles’s plan to deceive the Common, she would not have died. Thus you perceive the terrible consequences, however unintended, of concealing the truth, and will, I hope, understand why it is of such importance to me to reveal the truth to you now.

Earlier this year it was announced that a great dam would be built at the mouth of the Upper Kingdom River, supposedly in order to prevent logjams in the mountain notch upriver. I believe that the true purpose of this structure is to conceal the site of the burned village of New Canaan. To render it out of sight and, therefore, out of mind. It was this development, to further suppress the truth, that caused me to make up my mind to break my own long silence. I told your Kinneson father that I intended to do so, and showed him the genealogy that I recently added to my History. He begged me to reconsider. He implored me. He reminded me of my pledge, and said writing was no different than telling. He went so far as to warn me that the revelation I intended to make to you might make me the agent of my own destruction. I would, he said, become an accessory to my death as surely as if I had furnished the weapon that killed me.

“Why would you care what I reveal, brother?” I said. “You of all people. Who gave so much of your life, and nearly all of your fortune, to the abolition of slavery and the advancement of former slaves. Surely it cannot be the taint of Negro blood in your family?”

“Blood is blood, Pliny. There is no taint. I know who you are. It is an honor to have your ‘blood,’ as well as mine, in the veins of the boy. Already I see in him, and am much pleased by, the signs of scholarship and brilliance that have distinguished your life. What distresses me is how he and his descendants will be regarded, and how treated, in God’s Kingdom and beyond. I of all people? No. You of all people. You, who, after coming here, never once mentioned your own birthright as a Negro. You should know why I wish to shield our descendants from the hatred, scorn, and perhaps, still worse, the fate that befell the New Canaanites and our beloved Mary.”

James, it remains for me to tell you one thing more. My final words to you, or to any of our descendants who may discover this letter, have little to do with your ancestry or mine. Much ado has been made, of late, of my accomplishments over the course of my long life. My Academy. My ponderous old History. My Civil War service, and escape from Andersonville. The scholarship recently established in my name at the state university, of which you are the first recipient.

Yet here and now, with perhaps scant hours left to live, I say to you that I would trade each and every one of these worldly attainments—my school, my degrees, my war medals, all, all, all—for the opportunity to present you to your beloved birth mother, Mary Kinneson, and to show her what a fine and promising young man you have become, a son of whom I, and she, could never have been more proud.

Signed this Good Friday

midnight by your loving

father,

Pliny Templeton

Postscript: Attached is your family genealogy.

* * *

On the height of land south of the Landing, just above the original outlet of Lake Kingdom, Jim pulled off beside the tall granite obelisk carved with the words “Keep Away.” Not quite a year ago, he’d brought Frannie here to view the panorama of God’s Kingdom in its autumn colors. Later, the height of land became their favorite romantic rendezvous. A few times over the past summer Jim had driven out here, hoping to feel closer to Frannie.

Today a bluish haze hung in the air, a hint of the fall days to come. To the north, the Canadian peaks and the big lake between them were slightly indistinct, though Jim could make out the Île d’Illusion, and the Great Earthen Dam at the mouth of the Upper Kingdom River where, two hundred years ago, his great-great-great-grandfather Charles I had come upon the Abenaki fishing encampment. In the opposite direction, guarding the southeastern entryway to the Kingdom, were the White Mountains of New Hampshire and the long, north-and-south-running crease in the hills of the Upper Connecticut River where Abolition Jim had made his last stand against the federal troops at the second-longest covered bridge in the world. Visible to the west were one hundred miles of the Green Mountains. They, too, had kept God’s Kingdom closed off to itself, a territory but little known long after the rest of Vermont had been settled.

“I knew I’d married into a distinguished family,” Mom had said after Jim had burst into the newspaper office with the letter from Pliny and the genealogy, and explained what he’d discovered. “I just didn’t know how distinguished.”

“What should we do with them?” Jim asked his father.

Dad looked at Jim over the top of his reading glasses. “You’re the one who found them, son. I’d say it’s your call.”

Jim hesitated, but only for the briefest moment. “Print them both,” he said.

The editor nodded. “Gramp would be proud of you,” he said. That was all, but coming from Dad, it meant everything to Jim.

“Now,” Dad said, “you’ve got to get to college and your mom and I have a newspaper to get out. Let’s get this show on the road, folks.”

High on the ridgetop, Jim looked up the Lower Kingdom River Valley toward the village that had been his home for eighteen years. Already he was homesick. Yet, as he started his truck and headed over the height of land toward the other side of the hills, he knew in his heart that however far he might go, he would always take with him the stories, the mysteries, and the imperishable past of God’s Kingdom. For now, that was enough.