SMC

SMCONE OF THE GREAT SCIENTIFIC LEGACIES OF the Civil War was the work of the Army Medical Museum, founded in 1862 by Surgeon General William Hammond in response to the overwhelming tasks faced by the Union Army Medical Corps, which was ill equipped to handle the carnage on the battlefield and the epidemics in soldiers’ camps. The museum became the nation’s first federal medical research facility and compiled documentary evidence on war wounds and diseases that led to advances in treatment during and after the conflict. By 1863 the museum was collecting case histories, photographs, and anatomical specimens from many army hospitals and surgeons. In 1865 William Bell of Philadelphia became head of the museum’s photography department and began systematically documenting on camera the medical experiences, experiments, and travails of military physicians and the men they treated.

Bell’s work for the Army Medical Museum reflects his background both as a portrait photographer and as a Civil War veteran. In images like that of Henry A. Barnum, the wounded officer shown opposite, there is a sharp juxtaposition between the formal elegance of the composition and the brutal nature of the man’s wound, and between clinical detachment and emotional exposure. Bell deliberately posed such wounded survivors in such a way as to reveal distinctive features—in this case, Barnum’s scars where the bullet entered and exited (as reflected in the mirror). By portraying his subjects in uniform, Bell left them some dignity, but the haunted and heartbreaking expressions he captured on their faces were often those of despair, relief, or humiliation. These portraits served as important visual medical references for students and surgeons. Yet they were also poignant reminders of the subject’s individuality and stand as photographic works of art transcending the clinical images found in the typical medical textbook.

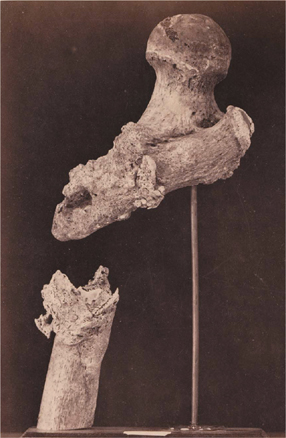

Bell also photographed skeletal remains held at the museum, including shattered skulls and broken bones, but those too were often personalized through the descriptions accompanying them, which named the victim when his identity was known. For example, the shattered bone pictured on this page was labeled “Lieutenant Goodwin, Deceased, Ununited Gunshot Fracture of the Upper Third of the Right Femur.” Naming the deceased helped transform an anatomical study into an act of remembrance at a time when the fate of many soldiers who fell in battle during the Civil War remained unknown.

Beginning in 1870, the museum published its collections in seven volumes entitled Photographic Catalogue of the Surgical Section of the Army Medical Museum. Each volume detailed case histories and documented wounds, treatments, and the results, providing medical students and surgeons with a great fund of knowledge. The vital research begun by the Army Medical Museum continues at the institution known today as the National Museum of Health and Medicine.  SMC

SMC

WAR WOUNDS Among the works by William Bell held at the Smithsonian American Art Museum are his photographs of Brigadier General Henry A. Barnum (FIRST IMAGE)—who returned to action after being shot through the abdomen in 1862 and was awarded the Medal of Honor—and the shattered femur of the late Lieutenant Goodwin (SECOND IMAGE).