STP

STPA LREADY A DYNAMIC VISUAL COMPONENT OF American life when the Civil War began, photography provided the public with captivating three-dimensional views of the conflict to experience at home. Those stereoviews were produced using cameras with two lenses, through which the photographer took two pictures. When viewed side-by-side on a stereoscope, these pictures were perceived as one three-dimensional image. Stereoscopes came in a variety of styles and were handsomely designed to blend in with Victorian parlor décor. Some were handheld devices, some were freestanding like the one at right, others were housed in handsome tabletop cabinets.

Many early stereoviews were pictures from around the world intended for armchair travelers. Informative and entertaining, they took on a more serious and somber tone during and immediately after the Civil War when curiosity about the conflict remained intense. Photographers produced images in series, often with explanatory text, including a set by Alexander Gardner showing how the Union buried its dead. Such images brought the war’s destructive impact home to the public, but other stereoviews made the conflict seem heroic, such as three-dimensional views of generals on their steeds. Some celebrated the Union victory by depicting Fort Moultrie or Fort Sumter (overleaf) after they were recaptured from Confederates in Charleston, South Carolina, in early 1865—or by portraying free African Americans standing outside their church in Richmond at war’s end.

Many stereoviews were sold late in the war, as indicated by the U.S. revenue stamps on their back. These stamps were required for photographs purchased beginning mid-1864. The stereoscope made such images a shared viewing experience and a topic of conversation for family members and friends, much like watching the news today. They allowed people to visually experience the history of their times in a way unsurpassed until motion pictures and newsreels were introduced.  STP

STP

IN-DEPTH VIEW This freestanding viewer holds a stereoview by photographer John P. Soule portraying the ruins of Fort Moultrie. Soule maximized the three-dimensional experience by showing a soldier standing guard by a tunnel through which one’s eyes would travel to the rubble beyond.

Interior of Fort Sumter at war’s end in 1865

House near York River, commandeered as headquarters of Union General Fitz-John Porter, 1862

Union troops preparing for battle near Fair Oaks, Virginia, 1862

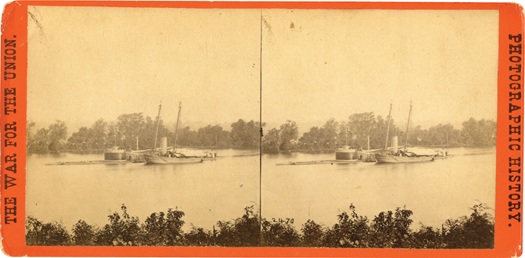

The monitor-class ironclad U.S.S. Canonicus (LEFT), taking on coal in the James River, 1864