DKA

DKAIN THE SPRING OF 1864 THE WAR IN VIRGINIA, AND the fate of the Confederate government in Richmond, came down to a contest between the two contrasting figures pictured here—Ulysses S. Grant, a common man risen to high command, slouching and a bit disheveled, never one to stand on ceremony or rest on his laurels; and Robert E. Lee, erect and dignified, impeccably attired, sword at his side, every inch the patrician, honor-bound to serve his state and region.

Three years earlier, the little-known Grant had to plead for a commission, while Lee had the distinction of being offered command of all U.S. forces in the field before he sided with the South. Now Grant was the Union’s general in chief and held sizable strategic advantages over Lee in men, weaponry, and supplies. Having won notable victories in the Western Theater, Grant also possessed the confidence of his soldiers and his president.

Lee, too, was esteemed by his troops and his commander in chief, but heavy losses at Gettysburg had left him without the capacity to take the offensive and achieve a decisive victory. His one hope now was to hold his ground and prolong the conflict until Northerners lost patience and turned against the war. That was still possible, but only if Lee could make Grant wilt like his ill-fated predecessors in Virginia did.

Their fateful contest began on May 5 in the densely wooded Wilderness, near Chancellorsville, where Lee had trounced Joseph Hooker a year earlier. Grant’s casualties in this battle were as great as Hooker’s, but he fought Lee to a draw and pushed on, assuring Abraham Lincoln that “there will be no turning back.” The opposing armies clashed again several days later at Spotsylvania, where Grant issued a memorable dispatch: “I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.” Pressed hard, Lee’s smaller army bent but did not break. When Grant attacked his entrenched foes on June 3 at Cold Harbor, he took horrific losses to no gain. Shifting course, he crossed the James River east of Richmond and descended on Petersburg. Lee moved quickly to defend that vital junction and prevent his capital from being cut off, but he dreaded being pinned down at Petersburg by Grant’s numerous and well-equipped forces. “This army cannot stand a siege,” Lee warned, and events in 1865 bore out that prediction.

For many Americans looking back in later years, the Civil War was exemplified by the contrast between these two commanders: who they were, how they fought, and what they represented. Lee would be remembered as the genteel champion of the old South and Grant as the gritty hero of the egalitarian Union, which awarded its highest rank and highest office to a man described by a fellow officer as “a marvel of simplicity, a powerful nature veiled in the plainest possible exterior.”  DKA

DKA

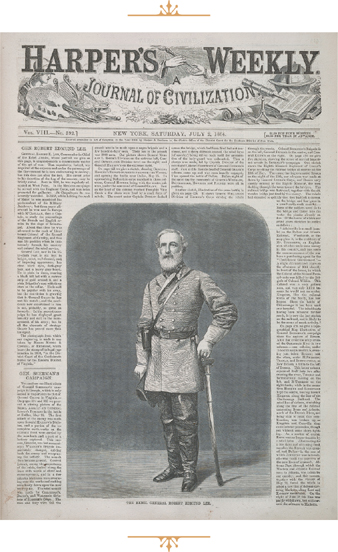

COMMANDING FIGURE Portrayed on the cover of Harper’s Weekly on July 2, 1864, Robert E. Lee was assessed there as follows: “In the present campaign he has displayed great tenacity and skill … but in all the elements of strategy Grant has proved more than his equal.”

GRANT IN THE FIELD Mathew Brady took this photograph of Ulysses Grant in June 1864 at City Point, Virginia, near Petersburg. Brady received permission to visit City Point only after his wife asked Julia Grant for help. The field chair in the photo is similar to the one at right, which Grant gave to Charles Goodsell of the 17th Michigan Infantry after the Battle of the Wilderness. The chair and Grant’s field glasses (ABOVE) are held now by the Smithsonian.