The Sculpin and the Sailfish, in league with six other fleet submarines, made the 5,000-mile passage to the Philippines with every expectation of a skirmish with Japan. Although they were armed for war on the 14-day voyage, war didn’t come—yet.

On November 8, the column of boats negotiated the minefields off the island fortress of Corregidor, a four-mile-long rock, honeycombed with tunnels and controlling the entrance to Manila Bay. The squadron then sailed another 30 miles northeast across the mountain-rimmed bay to the capital city, where they anchored in a nest within sight of Manila’s prosperous business district. Adm. Thomas C. Hart, the crusty 64-year-old commander-in-chief of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, immediately paid a visit to the famous boat his wife had christened. Both Mumma and Tucker impressed on him the need for an engine overhaul. “We had been running all over the Pacific and all of our engines were way beyond the number of hours used when they should have been overhauled,” Tucker explained. “So Admiral Hart told the skipper to sit right where he was and overhaul all four main engines before we did anything else. And that’s the only thing that kept us going for the next 15 months.”

The crews were briefed on local customs, and swarmed ashore on 48-hour leave. For them, the contrast to Honolulu was amazing. At Pearl, the military buildup had overwhelmed the city, causing such friction that there were frequent fights and intercession by shore patrols. But Manila, a sprawling metropolis, absorbed the rates easily. “It was the best liberty that I ever had,” said the Sculpin’s Rocek. “Everything was wide open. Anything you wanted, you could acquire. Liberty was cheap. Your money went two for one.”

Although life seemed carefree, there were clues to the impending war. Each time the Sailfish and Sculpin returned to Manila after training runs off Luzon, both were outfitted with enough stores for 90-day patrols—a sure indication the brass expected something. Also a steady parade of barges loaded with scrap iron bound for Japan from Manila had come to an end. And radio KZRF in Manila continuously broadcast sobering news from China and Europe, overshadowed by saber-rattling between Washington and Tokyo.

Hart, a veteran of World War I submarines, knew he was woefully mismatched in any face-off with the Japanese fleet, the largest armada ever assembled in the Pacific to that time. The newly arrived fleet boats were a help but hardly sufficient. Until the admiral’s arrival in 1940, the Asiatic station had been a refuge for those officers past their prime and winding down their naval careers. Hart immediately shook up the command and, in a highly unpopular move, ordered the evacuation of all naval dependents from the islands. He wanted the undivided attention of his men so they could concentrate on war training exercises. Also, there would be no need for a risky emergency evacuation should Japan launch a surprise attack.

Exactly how the United States could defend the Philippines was unclear. Three times in 1941 Allied plans had changed but eventually Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commander of American and Filipino ground forces, persuaded the War Department that his 100 long-range B-17 Flying Fortress bombers and 100 fighter planes could adequately hold the islands until the U.S. battle fleet from Pearl arrived to vanquish the Japanese. But Hart was skeptical. Decoded MAGIC intelligence pointed to a surprise Japanese attack, probably on Manila. As a result, the admiral began dispersing his fleet to British and Dutch harbors in the Indian Ocean.

In fact, a Japanese imperial conference on November 5 approved unprecedented military action—simultaneous assaults on Pearl Harbor, Manila, and Singapore, all aimed at neutralizing Britain and the United States, securing the oil reserves of the Dutch East Indies, and resuming the conquest of China. If the United States could be dealt a decisive blow—destruction of its Pacific fleet—then perhaps Roosevelt could be forced to the peace table. But Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Japanese navy, feared that failure to do so quickly could lead to a war of attrition, with the colossal industrial might of the United States eventually overwhelming Japan.

In Manila, submarine training drills quickened in November. The boats put out to sea on Mondays and returned on Fridays. Under way, the men of the Sailfish and Sculpin fired practice torpedoes and engaged in countless emergency drills. In port, the Sailfish, as usual, drew attention as the former Squalus. “General MacArthur decided to take a visit over to Corregidor and inspect the area that would become his headquarters in the event of war,” said Tucker. “We were assigned the job. Of course, the general was completely aloof, never went below decks and spent the entire trip on the cigarette deck [aft of the conning tower] surrounded by his staff. I don’t think he even talked to the captain.”

On November 27, Hart received an ominous dispatch from the chief of naval operations: CONSIDER THIS A WAR WARNING. NEGOTIATIONS WITH JAPAN LOOKING TOWARD STABILIZATION OF CONDITIONS IN THE PACIFIC HAVE CEASED AND AN AGGRESSIVE MOVE BY JAPAN IS EXPECTED WITHIN THE NEXT FEW DAYS. . . . EXECUTE AN APPROPRIATE DEFENSIVE DEPLOYMENT.

Immediately, the admiral sent his submarines on coastal scouting patrols while tightening security at Manila and Cavite with its huge stockpile of torpedoes. Under Operation Zed, the Sailfish and Sculpin embarked from Manila to circle Luzon, with torpedoes primed for war. Hart’s plan, once hostilities began, was to send his surface ships south to rendezvous with British, Dutch, Australian, and New Zealand vessels in hopes of blunting Japan’s southward drive. The submarines, the only naval weapons remaining in the Philippines, would be divided into three fighting units. Eight boats were to be sent afar to patrol Japanese bases; another eleven were to maintain station around Luzon on the lookout for enemy forces; and the remaining ten boats would be held in reserve for use against the Japanese fleet once it was located. Two other boats, including Sealion, were at Cavite, the U.S. naval station, for overhaul and thus unavailable.

On November 29, the day of the traditional Army-Navy football game, when the services stand down, many thought Japan would spring a surprise. But nothing happened.

On Sunday morning, December 7 (December 6, Hawaii time), the Sailfish and Sculpin returned to Manila to take on supplies. Capt. John Wilkes, commander of the Manila subs, was so fearful of attack by saboteurs or carrier-based bombers that he spread out the subs, anchoring them singly with armed seamen posted on deck. All small craft in the harbor were ordered to stay clear or risk being fired upon. Tension was so high that Bayles on the Sailfish strapped a .45-caliber handgun to his side in the duty section of the boat. The officers and most of the crew took brief liberty to participate in a standing softball game with other boat crews; the losers paid for a keg of beer afterwards. That evening, many of the officers went to the Army-Navy club to socialize, and crewmen straggled back to the boat, crashing in their bunks after hard drinking and partying ashore.

At exactly 0315 on December 8, the world as they knew it came to an end. A message was flashed to the submarines from Hart’s headquarters. Sailfish and the Sculpin signalmen jotted down the startling news: FROM COMMANDER ASIATIC FLEET . . . TO ASIATIC FLEET . . . URGENT . . . BREAK . . . JAPAN HAS COMMENCED HOSTILITIES . . . GOVERN YOURSELF ACCORDINGLY.

Aboard the Sailfish, the order was passed down the conning tower hatch to Bayles who went to awaken Cassedy, the fiery duty officer. “Cassedy got up and read the message. He half jumped out of his bunk and yelled, ‘Hold reveille!’” recounted Bayles. “I went into all the sleeping compartments and turned on the lights and said, ‘Wake up! The war has started!’ I remember someone in the after battery yelling back, ‘Bullshit!’”

A Japanese force of two battleships, three carriers, forty-five destroyers, and 100 transports bearing 43,000 Army troops and supported by 500 land-based aircraft, was en route from Taiwan to take Manila. As Mumma hurried to the Sailfish from the Army-Navy Club, a second message was received from Hart at 0330: CONDUCT UNRESTRICTED AIR, SURFACE AND UNDERSEAS WARFARE AGAINST THE EMPIRE OF JAPAN!

No bombs had fallen, so the crews could only wonder what had happened, completely unaware of the waves of Japanese warplanes that were decimating Pearl Harbor and the Pacific Fleet, including the battleship California (BB-44) to which Naquin was attached.

With the Sailfish crew assembled topside at daybreak, Mumma addressed them forcefully to prepare them for the boat’s long-awaited first war patrol. “This is what we have been trained for,” he began. “This is what our tradition has been for. We have never been tested. Our effort in World War I was negligible. We didn’t have the equipment to compare with the German U-boats. But now we are proficient, and now we are going to do a good job.” The captain then vowed to strike hard at the Japanese. “You are going to sail with the coldest-blooded man who ever captained a ship. I am going to carry you across the line. If anybody is scared, now is the time to get off.”

“Those were his exact words,” recalled Aaron Reese. “I will never forget them.”

At daybreak, with still no evidence of a Japanese attack or any word of what was happening elsewhere, the submarines in Manila prepared to depart. The Sailfish and the Sculpin, each manned by six officers and fifty-eight crewmen, sidled up to two oilers to top off fuel tanks and then to the sub tender Holland (AS-3) to take on ammunition and extra water. They exchanged practice torpedoes for live ones and installed the secret magnetic exploders already aboard. At 1000, the first air-raid siren—a false alarm—sounded over Manila as the sub captains mustered in Wilkes’s quarters for operational orders. He impressed upon each of them the danger and urged extreme caution. His assistant, division commander Stuart “Sunshine” Murray, was more emphatic: “Don’t try to go out there and win the Congressional Medal of Honor in one day. The submarines are all we have left. Your crews are more valuable than anything else. Bring them back.” Wilkes reminded the skippers to be sparing in their use of torpedoes because of a shortage but promised “amazing results” due to the magnetic exploders.

Mumma and Chappell returned to their boats and cast off, as enemy fighter planes and bombers descended over Clark Field, 50 miles to the north, where MacArthur’s air force was caught on the ground and destroyed.

In the harbor, the Sculpin, under cover of darkness on December 8, escorted the aircraft tender Langley (AV-3), the tanker Pecos (AO-6), and the destroyer tender Black Hawk (AD-9) toward Borneo. In an orderly procession, more boats exited Manila Bay through the night and into the next day, each with a different mission. On December 9 reserve subs, including Sailfish, raced down the bay to Corregidor. At 2100, the boat picked her way through the minefield and moved up the western coast of Luzon off loosely defended Lingayen Gulf, a likely landing point for Japanese infantry.

For two days, the boat scoured the area—submerged in the daytime, on the surface at night—as Mumma prowled the boat nervously. “Captain Mumma was a very intense individual. He had to know what was going on in his ship all the time,” recounted Tucker. “This attitude was fine in peacetime, but when the war began, he could not relax. He walked from bow to stern almost constantly the first four or five days we were under way. So when we made our first attack, he was completely exhausted.”

Contact with the enemy’s advance ships came on the fifth day (December 13) at 0230. Tucker, who was the officer of the deck at the time, confirmed three specks on the dark horizon (away from the moon). Because of the sub’s silhouette in the moonlight, the warships spotted the Sailfish and turned toward her, dropping depth charges as they came. “We dove and began listening on sound,” said Bayles of the hydrophones extended into the ocean below the sub. “According to the soundman, there were three sets of propellers. We knew then that three destroyers were operating together. Our soundman was very experienced.”

Mumma used sound bearings to set up an attack. At 0250, with the boat at periscope depth, he fired two torpedoes. “I was in the conning tower after the first exploded,” recalled signalman Claude Braun. “Mumma was on the periscope at the time. But there were no breaking-up noises of any vessel going down. He says to me, ‘Braun, see if you can see anything.’ So I stepped into the periscope and he said, ‘Leave it right there. We haven’t moved that much. You will see one or two [destroyers] up there.’

‘“I see a shape up there, sir, but I don’t see any fire or explosion. Nothing.’ I looked right at Mumma and his face turned white.

“Then the second torpedo hit at a longer range without exploding. When the second one was a dud and the guy on the hydrophone said he had a hit, Mumma said, ‘You got a hit?!’ And nothing happened, no explosion. His knuckles stood out as he gripped the periscope ears. And that’s when he put the ears up, lowered the scope, and said, ‘Take her down!’”

The submarine descended silently below 200 feet as the captain pondered what to do, shocked at the thought that at least one of the “foolproof” Mark VI exploders had not detonated, although the other might have sunk or at least damaged one of the warships. Overhead, the destroyers zeroed in.

“The soundman reported pinging by the enemy,” said Bayles. “When the old man heard it was pinging, he was still in the conning tower. He had a transmitter and a loudspeaker directly connected to the forward torpedo room where the soundman was stationed. So when the word came on his loudspeaker that ‘the [Japanese] are pinging us!’ and he knew that [Raymond] Doritty [RMlc] was on sound and was a first-class radioman, the old man said, ‘Ask Doritty what kind of whiskey he’s been drinking.’ Doritty replied, ‘If you don’t think it’s pinging, listen to it yourself.’ So Mumma did, at which time he voiced concern that we might have sunk an American destroyer. Ray said, ‘No, these aren’t American destroyers. American destroyers use a different frequency. This has to be [Japanese].’” According to Bayles, the revelation was a rude shock to Mumma. American destroyers operating with U.S. subs earlier had positively convinced submarine skippers that with sonar they could sink any submarine. “So, now the old man was convinced he was a dead duck.”

The destroyers obliged by lacing the ocean with twenty depth charges.

An ashen Mumma turned to his exec. “Mr. Cassedy, I’m going into my cabin.” Braun, witnessing the scene, was stunned. “I knew something had happened with Mort. It was a horrible thing to see, knowing this man.”

As it turned out, the depth charges exploded a safe distance away, causing minor damage as the Sailfish slithered away in the commotion. But the skirmish was enough to convince Mumma that he was not cut out for submarine warfare. His unnerving was a precursor to what soon would be revealed as a service-wide “skipper problem”—older boat captains coached in conservative tactics who were unwilling to aggressively attack enemy ships out of fear they would be doomed by unreliable torpedoes and enemy countermeasures.

On December 14, as scores of Japanese transports closed on Lingayen Gulf, Mumma, still in his cabin, told his exec in private that he wanted to return to Manila. Cassedy wrote up the request, encoded it, and bypassed Tucker, the communications officer, to take it directly to the radioman for broadcast. “The radioman reported back to me that the message had been sent and gave me the coded copy,” said Tucker. “I, of course, thought, ‘What message?’ I didn’t know anything about it. So I went back to my small room and decoded it. It had been very poorly phrased, I thought, but it implied that the skipper had broken down, which no one on the sub had any indication of, and desired to return Sailfish to Manila.”

Other submarines at sea intercepted the news with disbelief. Reuben Whitaker, executive officer of the Sturgeon (SS-187) on patrol off Taiwan, recalled the message: ATTACKED ONE SHIP . . . VIOLENT COUNTERATTACK . . . COMMANDING OFFICER BREAKING DOWN . . . URGENTLY REQUEST AUTHORITY TO RETURN TO TENDER.

On the run back to Manila, Braun spoke briefly with Mumma. “I told him, ‘Captain, I know we are going to Manila, and I suspect you are going to leave.’ He said, ‘Yes, I am.’ I wished him the best. He cried.”

The Sailfish anchored off Corregidor, then submerged during the day because of heavy bombardment of Manila, the naval base at Cavite, and Corregidor. That night, December 16, the boat slipped unnoticed across the bay to Manila where she anchored alongside the camouflaged tender Canopus (AS-9). The crew mustered on the deck. “It was the eeriest damn night,” recalled Reese. “A searchlight every once in awhile would flash around. Dark as hell. Then we hear Mumma’s voice out of the dark.”

According to Bayles, “With a teary voice, Mumma said he was sorry, that he was leaving, and that Lieutenant Commander [Richard George] Voge was coming aboard, was a good man, and was a classmate of Mumma’s. All he wanted us to do was give him the same loyal service as we had given to Mumma.” Voge had been skipper of the Sealion, which had been sunk by a Japanese bomber alongside the dock in Cavite, now in flames with its crucial stockpile of 233 torpedoes in ruins. The Navy tried to put the best face it could on the Mumma incident at a time when it was reeling from defeat on all fronts, and awarded him the Navy Cross for the attack and presumed sinking of the destroyer. “Looking back on it,” said Tucker years later, “I have a lot of respect for Captain Mumma for doing what he did. He realized he didn’t have it as a wartime sub skipper and said so. There were a lot of other skippers in Subs Asiatic Fleet who had less guts than he, who ran away from everything they saw for several months until the brass caught up with them and relieved them.”

The new skipper of the Sailfish, Voge, seemed much like Mumma. As one of the most experienced sub skippers in the fleet, the 37-year-old captain had served as skipper of the S-18 and S-33. Prior to that, he had seen duty in S-29, USS Pittsburgh (CA-4), Pecos, and USS Trenton (CL-11), and served a brief stint as engineering instructor at the Naval Academy. To the men aboard the Sailfish, Voge was all business. “He was very competent but rather cold. He looked like he was perpetually mad,” said Reese. But, as Braun put it, “conditions on the boat seemed more relaxed. It was very apparent to the men.”

Hart held Voge and Sailfish at Manila for five days as preparations were made for her second war patrol. Then on December 21, she embarked for the coast of Taiwan. Five days later, as Japanese troops rumbled across the northwest plains of Luzon toward Manila, Admiral Hart and two staff officers abandoned the city, bound for the Dutch naval base at Surabaya, Java, on the USS Shark (SS-174). On New Year’s Day, Wilkes withdrew all remaining submarines south toward Surabaya. Mort Mumma was among the last to be evacuated, boarding the USS Seawolf (SS-197), which sailed from Corregidor to Darwin on the north coast of Australia.

To the far north, the Sculpin patrolled the Philippine Sea. Each day was spent submerged, cruising at three knots in stifling heat. A breakdown of the sub’s air conditioning compounded the situation. At night, she surfaced and raced back and forth in her patrol quadrant, recharging batteries and looking vainly for enemy ships. Radio reports from other submarines revealed repeated failures of torpedoes despite perfect set-ups. They seemed to run under enemy vessels without exploding, or prematurely exploded for unknown reasons. On the Sculpin, the officers concluded the Mark XIV torpedoes were running too deep and adjusted the “fish” to run on the surface.

Nightly, lookouts were amazed by the strange phosphorescence of the ocean near the equator. The combination of tropical heat and abundant micro-organisms caused the sea to glow as the submarine moved across the surface, making the crew fearful of being spotted. Occasionally, large displays of luminescence flashed on and off like a lightbulb, with smaller displays created by schools of fish passing close to the submarine. It wasn’t until late in December that the Sculpin finally encountered enemy shipping moving in and out of Lamon Bay off Luzon. However, bad weather made it impossible for Chappell to attack.

Faced with the futility of an encounter in the patrol area, Chappell headed south toward Australia on January 9. The next day, off Mindanao, the southernmost large island of the Philippines, the boat intercepted a 3,000-ton Japanese cargo ship accompanied by a second ship. During a night surface attack, Chappell fired four torpedoes from a distance of 800 yards. Two exploded against the side of the ship, producing flames 200 feet high. The skipper and his lookouts watched as pinpoint beams from flashlights raced helter-skelter across the deck. Machine-gun fire erupted as the doomed ship listed, the shells forcing the Sculpin to dive. Below, crewmen listened for the first time to a ship in its death throes—the horrifying screech of metal collapsing and tearing, signaling the breakup of the freighter on its way to the bottom of the 30,000-foot-deep Philippine Trench.

On January 16, the submarine crossed the equator into the Southern Hemisphere for the first time. The next day the men surveyed the dense jungles and towering peaks of mysterious Borneo through the periscope. At sunset, the Sculpin surfaced off Balik-Papan to pick up a Dutch lieutenant pilot who guided the submarine inland on a jungle river in pitch blackness. “The jungle, towering on each bank of the river, gave the feeling of being in a black hole,” recalled Corwin Mendenhall, the boat’s junior ensign. The boat put in alongside a dock where rotting manila mooring lines were used to secure the vessel for refueling. Chappell went ashore for a meeting with the Dutch port captain, who informed him of the destruction of the U.S. Fleet at Pearl Harbor, the siege of MacArthur’s 200,000 troops in the Philippines, and the retreat of the Allies in Malaysia.

Quickly, the skipper returned to the boat where a string of lightbulbs had been strung over the deck to illuminate the refueling operations and the transfer of torpedoes from deck storage to the forward torpedo room. At dawn, the Sculpin set sail again, heading further south to Surabaya, Java, where she arrived on January 22.

Java was the main prize in the Japanese drive. Rich mineral supplies and tremendous reserves of petroleum ensured the strategic importance of the Dutch island. The harbor at Surabaya, a modern metropolis of 300,000 on the northern plains, contained a major Dutch submarine repair facility where a quick refit of the Sculpin began. The bearded, unwashed officers and crew were divided into two staggered groups and sent inland by train for a few days’ rest at a camp operated by the Dutch Submarine Force in the mountains at Malang 100 miles away. Rocek and seven other crewmen spent one day on horseback, riding through the countryside past lavish Dutch homes and encountering an elaborate Javanese wedding.

While the crew tried to forget the war, MAGIC intelligence tracked a Japanese fleet steaming toward Java from the Philippines. The Sculpin crew returned to the boat at once on January 30, departing in haste for the boat’s second war patrol. Chappell was ordered to rendezvous with the Sailfish south of the Philippines in hopes of intercepting the fleet. Wilkes put every available boat on line to sink the warships, sending eleven subs with the urgent call to “ATTACK. ATTACK. ATTACK. ATTACK.” But again, the force either failed to make contact or inflicted negligible damage because of defective torpedoes.

The Sailfish was able to successfully attack only one ship, a cruiser, in a daylight periscope approach off Mindanao. Voge launched four torpedoes at the warship, which was guarded by two destroyers. One exploded, damaging the cruiser’s propellers. The submarine had no chance to follow up since the destroyers immediately came after her. Voge took the boat to 260 feet for three hours, after which a periscope scan revealed no enemy ships in sight. The boat later surfaced and headed for a three-day refit at Tjilatjap, a poorly equipped port on the arid, dusty south coast of Java. She arrived on February 14 to a harbor crammed with British, Dutch, Australian, New Zealand, and American craft, all clamoring for spare parts, fuel, and food in the only bomb-free port left in Java.

As the Japanese relentlessly closed in, the outlook was grim. In three months of action, Wilkes’s twenty-eight subs had sunk a mere six ships, all freighters, at a cost of three boats—the Shark, Sealion, and S-36. Japanese torpedo bombers sank the British battleships Repulse and Prince of Wales off Singapore. English troops failed to thwart enemy troop landings on the Malay peninsula. Hong Kong was under siege. The Philippines were overrun. Wake Island, the Marianas, Solomon, Marshall, and Gilbert islands in the Central Pacific had fallen. Ships loaded with refugees dotted the Indian Ocean, leaving Java for safety in western Australia. Bombing runs on Darwin, the sweltering northern Australian port, left the new U.S. submarine logistics center in ruins. And, as the Sailfish prepared to cast off from Tjilatjap on her third war patrol on February 19, ninety-six enemy transports supported by forty warships moved on Java from the north and south.

The magnitude of defeat for the Allies was unimaginable to the beleaguered Sailfish crew, which was completely in the dark. “We had never been told what had transpired at Pearl Harbor. The Japanese knew, our politicians and diplomats knew, everybody at Pearl Harbor knew, but we poor bastards out there doing the fighting were not so privileged,” said Tucker.

On February 28 at 0030 in the Java Sea, the Sailfish made contact with a cruiser and two destroyers and prepared to attack. While closing in, Voge and his lookouts suddenly realized the cruiser might be the Houston and broke off the foray. Just as suddenly, the ship turned a searchlight in the direction of the submarine, forcing her to dive and pull clear. In fact, it was the Houston. She and the remnants of the combined Allied Asiatic fleet—five cruisers and five destroyers—were steaming west from the disaster at the Battle of the Java Sea in which two Allied cruisers and three destroyers were lost. The Houston and several other warships barely escaped. Now they were sailing into a Japanese trap in the Sunda Strait separating Java from Sumatra, where all ten ships would be lost.

The 100-foot Submarine Escape Training Tower as it appeared in 1943 at the national submarine school in Groton, Conn. (U.S. Navy photo)

A student surfaces in the Submarine Escape Training Tower with a clip on his nose while breathing through a Momsen lung. The breathing device, strapped around the chest, supplied oxygen during the 100-foot ascent.

A stern view of the USS Squalus on the day of her launch in 1938; note the cradle built under the submarine. The cradle carried the boat down a rail track and into the Piscataqua River at the far, open end of the ways at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. (U.S. Navy photo)

The Squalus at the fitting-out pier in Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on January 7, 1939. The number SI 1 was a hull designation number for shipyard purposes. Later, 192 replaced the number. (U.S. Navy photo)

Diver Martin Sibitzky about to begin his dive to the deck of the sunken Squalus on the morning of May 24, 1939. (courtesy of George Rocek)

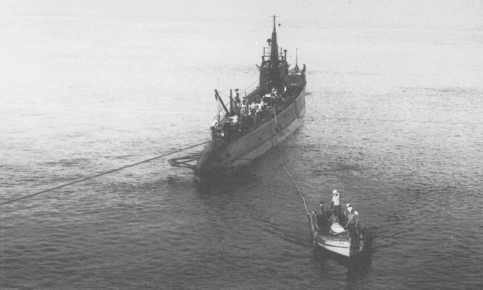

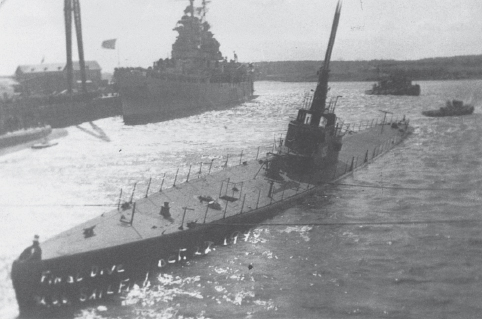

The USS Sculpin sends an air hose to the USS Falcon to boost air pressure during the salvage of the Sculpin’s twin sister ship, the Squalus. On August 12, 1939, divers used the Sculpin during the rescue and salvage operations. It was the Sculpin that discovered the whereabouts of the Squalus and her trapped crew. (U.S. Navy photo)

Squalus rises out of control during the first lift attempt of the salvage operations. This picture gave President Roosevelt the idea of renaming her the Sailfish. (USNI Collection)

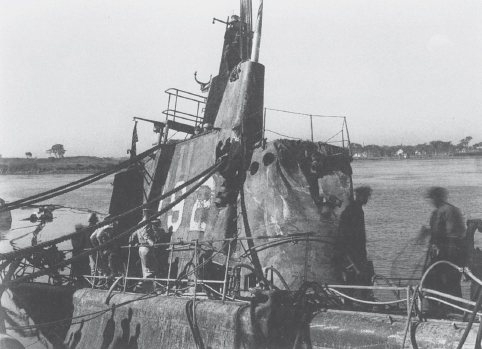

Battered conning tower of Squalus after she was towed back to Portsmouth. (U.S. Navy photo)

Some of the Squalus survivors and other crewmen at a reunion in late 1939. Those whose names are followed by an asterisk were not aboard for the ill-fated voyage. Bottom row, left to right, S. L. Savage,* Roland Blanchard, Allen Carl Bryson, Gavin J. Coyne, Basilio Galvan, Lawrence J. Gainor, and Donato Persico; second row, William D. Boulton, Harold C. Preble (a naval architect and the only civilian survivor), Lt. (jg) R. N. Robertson, Lt. Oliver F. Naquin (holding the silver sailboat given to him by the survivors), Lt. William T. Doyle Jr., Lt. J. C. Nichols, and Theodore Jacobs; third row, Raymond P. O’Hara, Charles A. Powell, Gerald McLees, Carlton B. Powell, S. C. Farwell,* Lloyd B. Maness, Arthur L. Booth, and Roy H. Campbell; top row, Charles Yuhas, Judson Bland, Warren W. Smith, Eugene Cravens, William Isaacs, Robert L. Washburn, Willard W. Blatti,* and Alfred G. Prien. (courtesy of Carl Bryson)

The Sculpin, circa 1940. (U.S. Navy photo)

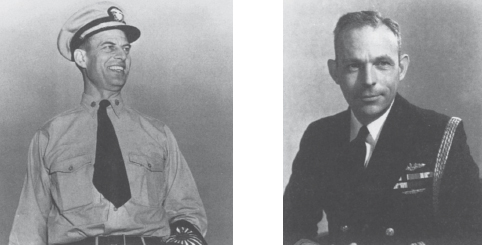

Left: Lt. Cdr. Lucius H. Chappell, skipper of the Sculpin for the boat’s first eight war patrols. (U.S. Navy photo) Right: Lt. Cdr. Morton Mumma, first captain of the Sailfish. (National Archives)

Boats tied up alongside USS Proteus, one of a small fleet of sub tenders in the Pacific during World War II. (U.S. Navy photo)

George Rocek, Sculpin engineman, on his return home from the warfront in 1943. Rocek was a survivor of the Sculpin’s last dive, was taken prisoner by the Japanese, then survived the sinking of a Japanese carrier and 19 months in prison camp. It was the Sailfish that sank the carrier where he was held captive with twenty other shipmates, (courtesy of George Rocek)

Sculpin crewmen in 1943. Kneeling, left to right, Carlos Tulao, Lt. Corwin Mendenhall, Weldon E. Moore, and Lt. John H. Turner; standing, John J. Pepersack, Alvin W. Coulter, Keith E. Waidelich, John B. Swift, John J. Hol-lenbach, Ralph S. Austin, Frank J. Dyboski, and Chesley A. DeArmond. (courtesy of George Rocek)

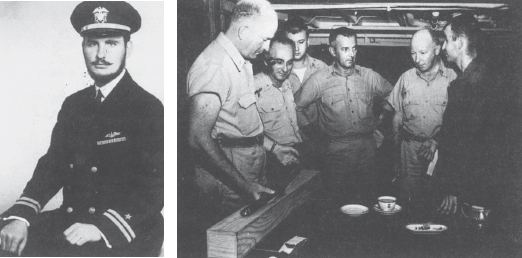

Admiral Nimitz presenting the Presidential Unit Citation to Capt. Robert Ward for the tenth war patrol of the Sailfish, July 1944, Pearl Harbor. During the patrol, the boat sank nearly 30,000 tons of enemy shipping, including the Japanese carrier Chuyo, on which twenty-one Sculpin POWs were imprisoned; only one (George Rocek) survived the sinking, (courtesy of Larry Macek)

The happy Sailfish crew on their return to Pearl Harbor after the tenth war patrol in 1944. Kneeling, left to right, Clemon E. Newkirk, Albert A. Kasuga, Robert Bradley, Lester Warburton, and John M. Good; standing, Lt. Joseph Sahaj, Thomas L. Ulhman, Henry K. Robertson, and Maurice D. Barnes. (courtesy of Larry Macek)

The footbridge spanning the Watarase River and linking the POW camp (against hillside in background) with the town of Ashio, where twenty Sculpin survivors were forced to labor in the Ashio copper mine. (courtesy of Arthur McIntyre)

The POW camp at Ashio, with barracks to left and right, (courtesy of Arthur McIntyre)

George Brown (left) before capture and (far right) after his liberation and arrival in Guam to discuss his ordeal with Admiral Lockwood and his staff. Brown was incarcerated at the Japanese secret prison of Ofuna for a year and a half and not listed as a POW. Later he was attached to a labor camp in central Japan where prisoners built a hydroelectric project. Forty-three Americans died there; Brown brought their ashes back to their relatives in the United States, (courtesy of George Brown)

The last dive of the Sailfish, October 27, 1945, in the Piscataqua River at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. The people of Kittery, Maine, and Portsmouth led a successful fight to keep the former Squalus from being scrapped in Philadelphia. The boat’s conning tower is today preserved at the shipyard as a memorial to the rescue of the Squalus survivors and as a World War II submarine shrine, (courtesy of Larry Macek)

Lowering the colors at the decommissioning of the Sailfish on Navy Day, October 27, 1945, in Portsmouth, N.H. (U.S. Navy photo)

George Rocek (left) talks with Capt. Bob Ward at the first Squalus/Sailfish/Sculpin reunion in Mobile, Ala., in 1979. Ward, who died less than a year later, was captain of the Sailfish when the boat sank the carrier Chuyo, where Rocek was held prisoner with twenty other POWs. (courtesy of George Rocek)

Adm. Oliver Naquin (right) talks with Rear Adm. Corwin Mendenhall (Sculpin veteran) at the national reunion of crews of Squalus / Sailfish / Sculpin, Baltimore, 1989. (courtesy of Carl Bryson)

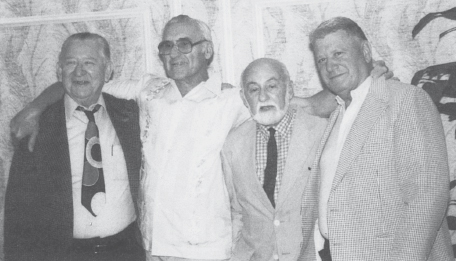

Left to right: Squalus survivor Jud Bland, Sculpin survivor George Rocek, and Squalus survivors Leonard de Medeiros and Danny Persico at reunion in 1993 in Pasadena, Calif. (courtesy of George Rocek)