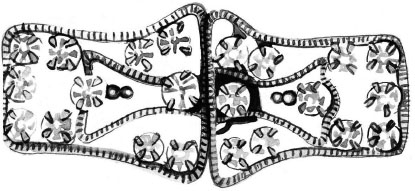

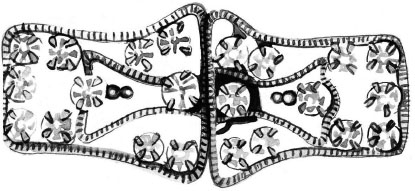

NOW A JEWEL in the button box, the diamanté clasp was once a glinting addition to a stage costume, an extravagance added to the short flared skirt of a pink taffeta dress that was one of several I wore when ‘dressing up’ at my grandma’s. My mum wore the pink taffeta when performing as a pupil of the Miss Iliffe School of Dancing, something she did many times during the 1930s and ’40s. A golden-yellow gown of hers had an emerald green sequined heart beating on its bodice; a scarlet and white blouse, drum majorette-style, fastened with large gilt buttons. Stage clothes catch the light and need to be seen from a distance. It is as well for them to sparkle now and then.

The short pink dress was made for ‘Forget-Me-Not Lane’, a lively troupe number, each girl dressed in the same style but a different colour, wartime expediency resulting in a vivid display. The dancers appeared from the wings in a line, arms linked round waists, low kicks rising higher and higher as they circled in formation, separating to make the spokes of a wheel and then coming together again in a Busby Berkeley kaleidoscope of pattern, kicks and colour. Anyone who has seen 42nd Street knows the pleasurable slam of multiple taps striking the boards. ‘Forget-Me-Not Lane’ was designed to make the audience sit up. Even without a diamanté clasp, the pink dress was obviously meant for the stage.

Buckles or buttons set with brilliants are all about show – and always have been. Aristocrats of earlier centuries had buttons decorated with diamonds. The French court took elaboration to extremes: the Comte d’Artois wore diamond buttons set with miniature watches; Louis XV had his own button-maker. Marcasite was a cheaper mineral substitute; cut steel also glittered and flashed like the diamonds courtiers wore. Cut-steel buttons became extremely fashionable and made the fortunes of several Birmingham manufacturers, notably Matthew Boulton (who later worked with Josiah Wedgwood to produce ceramic buttons). By the late nineteenth century – by which time women were the ones doing the sparkling – lustre glass had replaced steel; the majority of Victorian and Edwardian dazzlers are made from this material. Their popularity for eveningwear led to millions being imported, mostly from France and Czechoslovakia. Where would evening dress be without a little razzle dazzle?

Shoes set with brilliants were among those on sale during Chesterfield’s 1914 Shopping Festival. In 1929, The Needlewoman insisted, ‘You must have a lamé evening wrap.’1 This was the era in which some lucky, unknown woman arrived for dinner wearing a metallic-studded shawl that later came to my great-aunt Eva (probably via one of the big-house sales my great-grandfather frequented). Rich, poor, middling: all ranks of society like to dress up. The 1920s and ’30s, as well as liking beaded and jewelled frocks for eveningwear and the Charleston, were agog for fancy dress, Cleopatras glittering among the Pierrots and Pierrettes.

The ‘brilliant’ cut diamonds favoured today were introduced during this period. By the 1950s, costume jewellery promised never-ending sparkle and even the most sedate matron wore a jewelled brooch on her lapel. Brilliance was itself subject to fashion: yellower diamonds found favour in the 1930s; fifties women preferred white diamonds in their necklaces and floral sprays.

Diamanté sparkle, long dresses, dinner dances. Those 1950s evening gowns were accessorised with little bags for the powder compact every woman carried (the powder compact was that era’s go-to gift for women at works Christmas dos). Compacts also glittered and shimmered. A fifties compact given to me has a black surface with two silver jewelled palm trees and a gold Bambi (suggesting a designer who perhaps did not know when to stop). Dinner dances provided occasions for my mum to wear long black velvet gowns with tight bodices and halter necks. Annie made her a white bolero to soften those backless gowns, a silver lamé dress and a blue taffeta evening coat with a mandarin collar; a pink net skirt she transformed from stage-to eveningwear required hours of hand sewing to create an arc of black net bead-studded flowers which swept from calf to waistband. My mum completed her Coty L’Aimant evenings with elbow-length white (or black) cotton gloves.

Formal wear required appropriate jewellery: a necklace of graduated ‘diamond’ slabs, crystal beads twinkling rainbows, earrings dangling like chandeliers. An ‘Instant Paris’2 addition recommended by Vogue included a glittering necklace, rhinestone earrings and bracelets, or a string of graduated pearls. This passion for all things sparkling suited the shiny new post-war world. (It even extended into home furnishings: chrome cake stands were popular wedding gifts). Make-up too had its own shimmer. In 1958, Elizabeth Arden promoted a new foundation, ‘Veiled Radiance’;3 Goya advertised thirteen ‘Golden Girl Cosmetics’ in 1965 and ‘a totally new lip finish that turns your lipstick shades into shimmer shades!’4 (for 6s 6d). Shimmery nail polish set the party-goer back 6s.

My parents were among the 5 million people who, by 1961, went to a dance each week; they also liked to invite friends back. For my parents’ circle, after-hours socialising meant dancing (‘Bobby’s Girl’, ‘Move Over Darling’, ‘Fever’…), nibbles and drinks, which is where the cocktail cabinet came in. The cocktail cabinet arrived in 1959. It was described as a wine cabinet on the receipt, which sounds more restrained and decorous. It did not hold wine, however (which, back in the day, was mostly Mateus Rosé) but spirits and the mixes for whisky mac, gin and tonic, gin and French, gin and It. The mirrored interior held a heavy soda siphon, a goblet with a chrome lid for ice, and numerous glasses, some of which were so fine you hardly dared put them to your lips.

Three metal cocktail sticks with billiard-ball tops – red, yellow, green – slotted into a holder inside the left-hand door; the inside-right held a lemon squeezer. If it seems odd that integral cocktail sticks were supplied in traffic-light colours, this was before the breathalyser, in the days of ‘one for the road’. With both cabinet doors open and a mirrored counter resting on an open drawer, the whole was an invitation to pleasure. A narrow drawer held coasters and rinky-dink cocktail stirrers picked up in one place or another: I remember a giraffe with an especially elongated neck and a slim swizzle-stick with a pineapple atop. There were toothpicks for piercing maraschino cherries and tiny forks for skewering cocktail onions. Later came Chiplets, paprika-sprinkled hard-boiled eggs, and grapefruits studded with cubes of cheese, or cheese alternating with pineapple and cocktail onions. How sophisticated it seemed to me, the mirrored interior giving the whole a glamorous sparkle capable of unsettling the tipsy drinker who, while leaning in for a top-up, could see their face in several planes at once. The cocktail cabinet belonged to an adult world of music, perfume, laughter and smart dresses, although the party clothes of my mum’s that I remember best are the ones she wore to go out. They complete a memory of soft fur, intense wafts of newly applied scent, and long cold earrings brushing against me as she leaned in for a goodnight kiss.

Just as, years later, I uncovered treasures at Annie and Eva’s, as a child I loved to explore my mum’s wardrobe and look at her clothes. I also discovered the mysteries of her dressing table: the cigarette lighter shaped like a lipstick, the shimmery beaded purse which held sixpence for the ladies’ cloakroom; the pan-cake make-up and the eyeliner with its slender toothbrush-like applicator that, when discarded, made a perfect doll’s toothbrush; the lace-edged handkerchiefs for patting stray lipstick; and always the faint drift of face powder in the corner of a drawer. Like Kezia in Katherine Mansfield’s ‘Prelude’ discovering a bead, needle and stay button caught between the floorboards of an empty room, I was fascinated by these small-scale intimations of a grown-up world. My mum had a little plastic cape to protect her shoulders from hair combings when she sat at her triple-mirrored dressing table. Who sits at a dressing table now?

Evening dresses were shorter, earrings and dress rings larger, and my parents made occasional forays to the Carlton, a nightclub with gaming tables and a floor show that attracted singers such as Jackie Trent and Nellie Lucker. This sophisticated venue was something I could only imagine, but its name intrigued me because of those scented goodnight kisses. Even now, the name has a certain allure and conjures up little lights on tables, red plush, dicky bows and twinkling earrings. This was the era in which my mum wore a slip of a dress in tangerine and the scarlet one in tiered chiffon that came to me when I was in my twenties. At that time I also shook out an old stage dress of hers and wore it to a party. White sateen, with a soft full skirt, it made me want to sway and swirl. The dance changes, but a taste for dressing up, once discovered, is rarely lost.