Appendix

Literary Narrative: Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” (1927)

Hemingway’s brief story – it has fewer than 1,500 words – focuses on a conversation between an unnamed male character and Jig, the woman who has been impregnated by the male character (one can assume). The story is set on a hot day at a train station in Spain, in a valley through which the Ebro river flows. As they wait for the train to Madrid, the two characters briefly discuss the appearance of the landscape surrounding them (specifically, Jig mentions that the hills across the valley look like white elephants), then order drinks and engage in a sometimes tense conversational exchange about the possibility of Jig’s having an abortion. When the story ends, with the characters expecting the train to arrive momentarily, it remains unclear what course of action they will pursue – although the closing lines perhaps suggest that Jig has acceded to the male character’s suggestion that she get the abortion, or at least decided that any further discussion of the matter with him would be fruitless.

Page numbers inserted in brackets in the text correspond to those in Hemingway ([1927] 1987).

[p. 211] The hills across the valley of the Ebro were long and white. On this side there was no shade and no trees and the station was between two lines of rails in the sun. Close against the side of the station there was the warm shadow of the building and a curtain, made of strings of bamboo beads, hung across the open door into the bar, to keep out flies. The American and the girl with him sat at a table in the shade, outside the building. It was very hot and the express from Barcelona would come in forty minutes. It stopped at this junction for two minutes and went to Madrid.

“What should we drink?” the girl asked. She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.

“It’s pretty hot,” the man said.

“Let’s drink beer.”

“Dos cervezas,” the man said into the curtain.

“Big ones?” a woman asked from the doorway.

“Yes. Two big ones.”

The woman brought two glasses of beer and two felt pads. She put the felt pads and the beer glass on the table and looked at the man and the girl. The girl was looking off at the line of hills. They were white in the sun and the country was brown and dry.

“They look like white elephants,” she said.

“I’ve never seen one,” the man drank his beer.

“No, you wouldn’t have.”

“I might have,” the man said. “Just because you say I wouldn’t have doesn’t prove anything.”

The girl looked at the bead curtain. “They’ve painted something on it,” she said. “What does it say?”

“Anis del Toro. It’s a drink.”

“Could we try it?”

[p. 212] The man called “Listen” through the curtain. The woman came out from the bar.

“Four reales.” “We want two Anis del Toro.”

“With water?”

“Do you want it with water?”

“I don’t know,” the girl said. “Is it good with water?

” “It’s all right.”

“You want them with water?” asked the woman.

“Yes, with water.”

“It tastes like liquorice” the girl said and put the glass down.

“That’s the way with everything.”

“Yes,” said the girl. “Everything tastes of liquorice. Especially all the things you’ve waited so long for, like absinthe.”

“Oh, cut it out.”

“You started it” the girl said. “I was being amused. I was having a fine time.”

“Well, let’s try and have a fine time.”

“All right. I was trying. I said the mountains looked like white elephants. Wasn’t that bright?”

“That was bright.”

“I wanted to try this new drink. That’s all we do, isn’t it – look at things and try new drinks?”

“I guess so.”

The girl looked across at the hills.

“They’re lovely hills,” she said. “They don’t really look like white elephants. I just meant the coloring of their skin through the trees.”

“Should we have another drink?”

“All right.”

The warm wind blew the bead curtain against the table.

“The beer’s nice and cool,” the man said.

“It’s lovely,” the girl said.

“It’s really an awfully simple operation, Jig,” the man said. “It’s not really an operation at all.”

The girl looked at the ground the table legs rested on.

“I know you wouldn’t mind it, Jig. It’s really not anything. It’s just to let the air in.”

The girl did not say anything.

“I’ll go with you and I’ll stay with you all the time. They just let the air in and then it’s all perfectly natural.”

“Then what will we do afterwards?”

“We’ll be fine afterwards. Just like we were before.”

“What makes you think so?”

“That’s the only thing that bothers us. It’s the only thing that’s made us unhappy.”

[p. 213] The girl looked at the bead curtain, put her hand out and took hold of two of the strings of beads.

“And you think then we’ll be all right and be happy.”

“I know we will. You don’t have to be afraid. I’ve known lots of people that have done it.”

“So have I,” said the girl. “And afterwards they were all so happy.”

“Well,” the man said, “if you don’t want to you don’t have to. I wouldn’t have you do it if you didn’t want to. But I know it’s perfectly simple.”

“And you really want to?”

“I think it’s the best thing to do. But I don’t want you to do it if you don’t really want to.”

“And if I do it you’ll be happy and things will be like they were and you’ll love me?”

“I love you now. You know I love you.”

“I know. But if I do it, then it will be nice again if I say things are like white elephants, and you’ll like it?”

“I’ll love it. I love it now but I just can’t think about it. You know how I get when I worry.”

“If I do it you won’t ever worry?”

“I won’t worry about that because it’s perfectly simple.”

“Then I’ll do it. Because I don’t care about me.”

“What do you mean?”

“I don’t care about me.”

“Well, I care about you.”

“Oh, yes. But I don’t care about me. And I’ll do it and then everything will be fine.”

“I don’t want you to do it if you feel that way.”

The girl stood up and walked to the end of the station. Across, on the other side, were fields of grain and trees along the banks of the Ebro. Far away, beyond the river, were mountains. The shadow of a cloud moved across the field of grain and she saw the river through the trees.

“And we could have all this,” she said. “And we could have everything and every day we make it more impossible.”

“What did you say?”

“I said we could have everything.”

“We can have everything.”

“No, we can’t.”

“We can have the whole world.”

“No, we can’t.”

“We can go everywhere.”

“No, we can’t. It isn’t ours any more.”

“It’s ours.”

“No, it isn’t. And once they take it away, you never get it back.”

“But they haven’t taken it away.”

“We’ll wait and see.”

[p. 214] “Come on back in the shade,” he said. “You mustn’t feel that way.”

“I don’t feel any way,” the girl said. “I just know things.”

“I don’t want you to do anything that you don’t want to do –”

“Nor that isn’t good for me,” she said. “I know. Could we have another beer?”

“All right. But you’ve got to realize –”

“I realize,” the girl said. “Can’t we maybe stop talking?”

They sat down at the table and the girl looked across at the hills on the dry side of the valley and the man looked at her and at the table.

“You’ve got to realize,” he said, “that I don’t want you to do it if you don’t want to. I’m perfectly willing to go through with it if it means anything to you.”

“Doesn’t it mean anything to you? We could get along.”

“Of course it does. But I don’t want anybody but you. I don’t want anyone else. And I know it’s perfectly simple.”

“Yes, you know it’s perfectly simple.”

“It’s all right for you to say that, but I do know it.”

“Would you do something for me now?”

“I’d do anything for you.”

“Would you please please please please please please please stop talking?”

He did not say anything but looked at the bags against the wall of the station. There were labels on them from all the hotels where they had spent nights.

“But I don’t want you to,” he said, “I don’t care anything about it.”

“I’ll scream,” the girl said.

The woman came out through the curtains with two glasses of beer and put them down on the damp felt pads. “The train comes in five minutes,” she said.

“What did she say?” asked the girl.

“That the train is coming in five minutes.”

The girl smiled brightly at the woman, to thank her.

“I’d better take the bags over to the other side of the station,” the man said. She smiled at him.

“All right. Then come back and we’ll finish the beer.”

He picked up the two heavy bags and carried them around the station to the other tracks. He looked up the tracks but could not see the train. Coming back, he walked through the bar-room, where people waiting for the train were drinking. He drank an Anis at the bar and looked at the people. They were all waiting reasonably for the train. He went out through the bead curtain. She was sitting at the table and smiled at him.

“Do you feel better?” he asked.

“I feel fine,” she said. “There’s nothing wrong with me. I feel fine.”

Narrative Told during Face-to-Face Communication: UFO or the Devil (2002)

This story, which I’ve titled UFO or the Devil, was told by Monica, a pseudonym for a 41-year-old African American female, to two white female fieldworkers in their mid-twenties engaged in a research project on the dialects spoken in western North Carolina.

The narrative was recorded on July 2, 2002, in Texana, North Carolina, near where the events recounted are purported to have occurred (see Figures 1 and 2 below for maps).1 Below I provide both a sketch of Texana and a transcript of the narrative, but it should be noted at the outset that the interview during which Monica told this story was not a structured, sociolinguistic interview per se. Rather, the fieldworkers happened to encounter Monica while visiting her sister, whom they had already interviewed on several occasions. After establishing a rapport with Monica, they then retrieved their recording equipment from their car and continued what had become by that point a relatively informal conversational interaction.

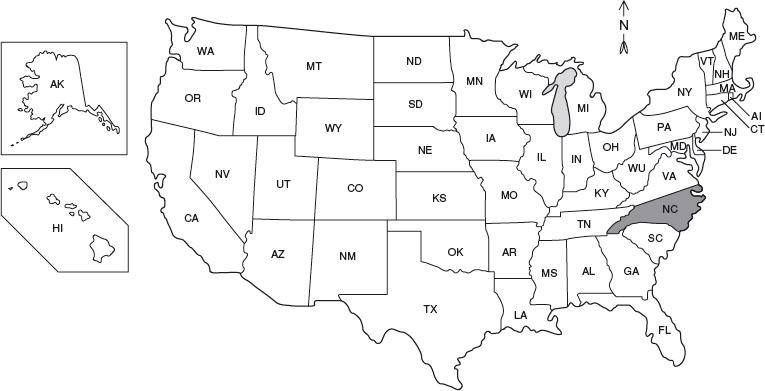

Figure 1 Location of the state of North Carolina within the U.S.

Mapping software provided courtesy of John Adamson, Management Information Specialist, Texas AgriLife Extension, Texas A&M University System. <http://monarch.tamu.edu/~maps2/>

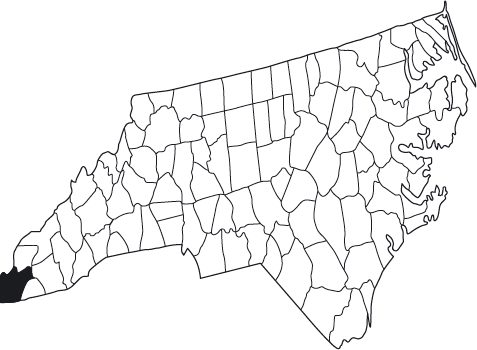

Figure 2 Location of Cherokee County within North Carolina Mapping software provided courtesy of John Adamson, Management Information Specialist, Texas AgriLife Extension, Texas A&M University System. <http://monarch.tamu.edu/~maps2/>.

The fieldworkers initially prompted Monica with questions about her family background and her experiences in places she had lived, but once the interaction got underway it was largely Monica who directed the flow of the discourse, apart from a few follow-up questions by her interlocutors. Thus the story that I have titled UFO or the Devil (based on a phrase used by Monica in the first line) was told as part of a larger sequence of narratives through which Monica cumulatively presents a portrait of herself.2 In this self-portrait, Monica emerges as someone who was profoundly shaped by experiences in her family and community settings; who has explored multiple educational and career options, while living in several urban centers in addition to the more rural environs of Texana; and who is now in a position to look back at these formative experiences and gauge their impact on her current sense of self. As the transcript reveals, the narrative that I have excerpted from this much more extended interaction (the total duration of the tape-recording is more than 145 minutes) concerns not only Monica’s and her friend’s encounter with what Monica characterizes as a supernatural apparition – a big, glowing orange ball that rises up in the air and pursues them menacingly – but also Monica’s and Renee’s subsequent encounter with Renee’s grandmother, who disputes whether the girls’ experience with the big ball really occurred.

Located in Cherokee County, which is otherwise nearly totally white,3 Texana is a community consisting almost exclusively of African Americans; indeed, with about 150 residents, only 10 of whom are white, Texana is the largest black Applachian community in western North Carolina (Mallinson 2006: 69, 78). It is situated about one mile from Murphy, North Carolina, as well as other small white communities, and interactions among residents of Texana and these neighboring communities are sometimes tense (Mallinson 2006: 78). Indeed, as Mallinson discusses (2006: 71–6; cf. Mallinson 2008), the ethnic profile of members of the Texana community is considerably more complicated than this initial characterization would suggest. As Mallinson notes, “Texana residents are descendants of African, Cherokee, Ulster Scots-Irish, and Irish-European ancestors – which is the case for many black Appalachians, particularly those whose ancestors were slaves” (2006: 71). In consequence, feeling that the ethnic categories listed on questionnaires and surveys are unable to capture their complex heritage, most Texanans self-identify as black, since this designation refers to skin color rather than a pariticular ethnic or racial background (2006: 75).

The complex ethnic situation in Texana bears importantly on the way Monica uses her narrative to position herself and others – to invoke a concept that I discuss more fully in chapter 3 of this book. From the start of her narrative, Monica indexes herself as a member of the enclave African American (or at least non-white) community based in Texana and positioned contrastively against the surrounding, predominantly white population of Cherokee County. (As my discussion in chapter 3 suggests, this formulation captures only part of the positioning logic at work in the narrative.) Prior to the time of the interview, Monica had written features for a local newspaper during black history month, and she had also spoken openly about how racism and sexism had prevented her from advancing in the medical field despite her completion of a training course for emergency medical technicians (Mallinson 2006: 89, 97). More generally, as Mallinson remarked in a personal communication, “From what I learned about [Monica], race is very salient to her... she told us a lot of stories about gender/racial prejudice that she faced in her life, how racist Cherokee County is, how she felt growing up in Texana and what happened after she moved to Dayton, Atlanta, etc.”

In the following transcript, I have segmented the narrative into numbered clauses for the purposes of analysis; I have also listed the transcription conventions used to annotate the story. Further, readers can access a sound file containing a recording of Monica’s story at the following URL: <http://www.ohiostatepress.org/journals/narrative/herman-audio.htm>. Indeed, given the importance of prosody in Monica’s narrative, readers may wish to wish to consult this online resource as they assess my subsequent analysis rather than rely solely on my own attempt to capture relevant prosodic details in the transcript.

Adapted from Jefferson 1984; Ochs et al. 1992; Schegloff, “Transcription” [n.d]; and Tannen 1993.

| ... { } | represents a measurable pause, more than 0.1 seconds; approximate durations given in curved brackets ( ... {.3} = a pause lasting 0.3 seconds) |

| .. | represents a slight break in timing |

| - | a hyphen after a word or part of a word indicates a self-interruption or “restart” by the current speaker |

| * | indicates a rising intonational contour, not necessarily a question |

| . | indicates a falling, or final, intonation contour, not necessarily the end of a sentence |

| , | indicates “continuing” intonation (“more to come”), not necessarily the end of a clause |

| : | indicates the prolongation of a sound just preceding it; more than one colon indicates a sound of even longer duration |

| _ | underlining indicates stress or emphasis, either through increased loudness or heightened pitch. UPPER CASE letters indicate extremely loud talk, and UNDERLINING is added for even louder speech productions |

| °° | Two degree signs indicate that the talk between them is noticeably quieter than the surrounding discourse |

| ↑↓ | The up and down arrows mark rises and and falls of pitch; up arrows indicate sharper rises in pitch than those marked with underlining in stressed or emphasized words |

( ) ) | indicates downward change of pitch within the boundaries of a word; inserted before the syllable in which the change occurs |

( ) ) | indicates upward change of pitch within the boundaries of a word; inserted before the syllable in which the change occurs |

| > < | indicate that the talk between these symbols is compressed or rushed relative to the surrounding discourse |

| < > | indicate that the talk between these symbols is markedly slower than the surrounding discourse |

| [ | indicates overlap between different speakers’ utterances |

| = | indicates an utterance continued across another speaker’s overlapping utterance |

| // | enclose transcriptions that are not certain |

| ( ) | enclose nonverbal forms of expression, e.g. laughter unaccompanied by words |

| [....] | in short extracts indicates omitted lines |

| MONICA: | (1) So that’s why I say..UFO or the devil got after our black asses, |

| (2) for showing out. | |

| (3) > I don’t know what was > | |

| (4) but we walkin up the hill, | |

| (5) this ↑ way, comin up through here. | |

| INTERVIEWER 1: | (6) Yeah. |

| MONICA: | (7) And..I’m like on this side and Renee’s right here. |

| (8) And we walkin | |

| (9) and I look over the bank* ... {.2} | |

| (10) and I see this ... {.3} < BI:G BALL>. | |

| (11) It’s glowin, ... {.2} | |

| (12) and it’s orange. ... {.3} | |

| (13) And I’m just like ... {1.0} | |

| (14)°“nah..you know just-° nah it ain’t nothin” you know. | |

| (15) And I’m still walkin you know* | |

| (16) Then I look back over my side again, | |

| (17) and it has °risen up*° ... {2.0} | |

(18) And I’m like “( )SHI::T.” ... {.5} you know. )SHI::T.” ... {.5} you know. | |

(19) So but Re( )nee- I still ain’t say nothin to her )nee- I still ain’t say nothin to her | |

| (20) and I’m not sure she see it or not, ... {.2} | |

| (21) so I’m still not sayin anything | |

| (22) we just °walkin.° ... {1.0} | |

| (23) Then I look over the bank again | |

| (24) and I don’t see it, | |

| (25) and then I’m like °“well, you know.”° ... {.3} | |

| (26) But then ... {.2}forsome reason I feel some heat > or somethin other < | |

| (27) and I <look back> | |

| (28) me and Renee did at the same time | |

| (29) it’s right behind us. ... {1.0} | |

| (30) We like- ... {.2} /we were scared and-/.. | |

| (31) “AAAHHH” you know= | |

| INTERVIEWER 2: | (32) (laughs) |

| MONICA: | (33) >=at the same time. < |

| (34) So we take off runnin as fast as we can, | |

| (35) and we still lookin back | |

| (36) and every time we look back it’s with us. ... {.5} | |

| (37) It’s just a-bouncin behind /us/ | |

| (38) it’s no:t.. > touchin the ground, < | |

| (39) it’s bouncin in the air. ... {.5} | |

| (40)°Just like this ... {.2} behind us° | |

| (41) as we run. ... {1.0} | |

| (42) We run all the way to her grandmother’s | |

| (43) and we open the door | |

| (44) and we just fall out in the floor, | |

| (45) and we’re cryin and we scre:amin | |

| (46) and < we just can’t breathe.>... {.3} | |

| (47) We that scared.. | |

| (48) “What’s wrong with you all” you know | |

| (49) and we tell them..you know..what had happened. | |

| (50) And then her grandmother tell us | |

| (51) it’s some ↓ mineral.. this or ↓ that | |

| (52) they just form | |

| (53) bah bah ↓ bah ↓ bah | |

| (54) and ... {.3} the way we ↓ ran..it’s the ↓ heat | |

(55) and..you know ... {.3}Bull( )shit. )shit. | |

| (56) You know..but so I never knew in my LIFE ... {.2} about that | |

| (57) but we didn’t do that anymore. ... {1.0} | |

| Interviewer 1: | (58) Right. |

| MONICA: | (59) When dark goddamn came |

| (60) our ass was at home. |

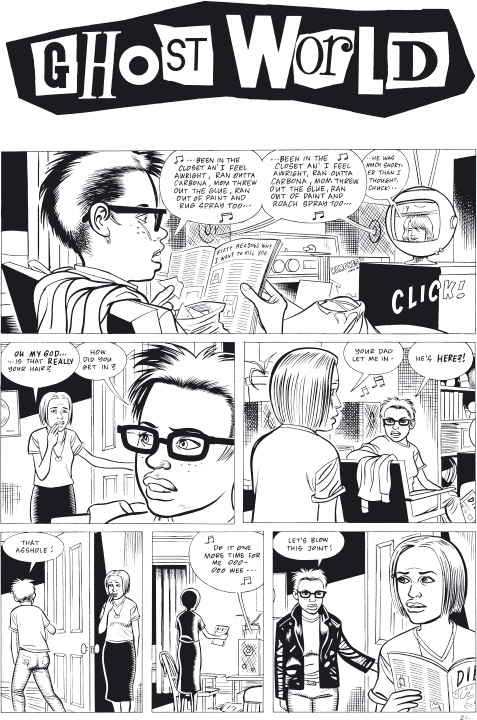

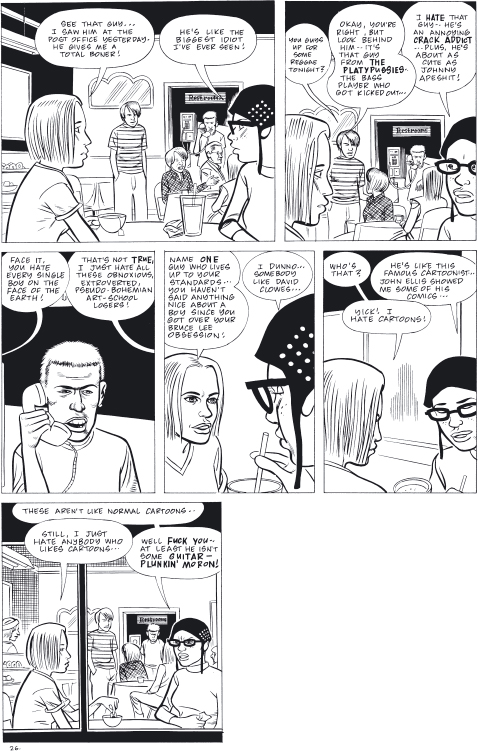

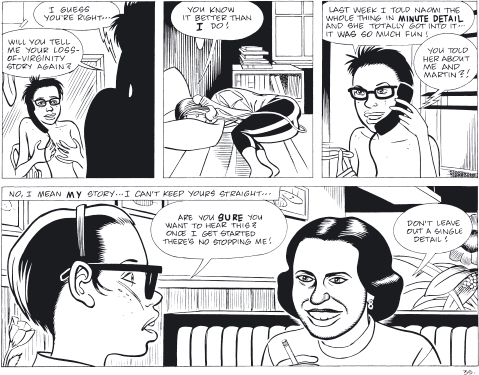

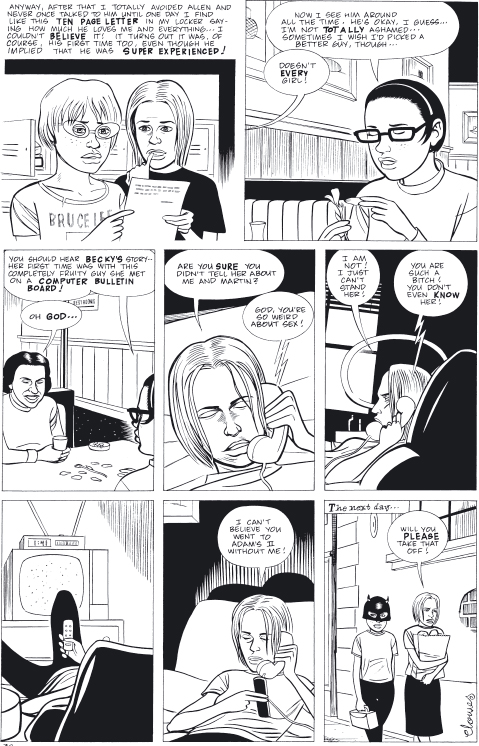

Excerpted Panels from Ghost World (1997), a Graphic Novel by Daniel Clowes

Focusing on two teenage girls trying to navigate the transition from high-school to post-high-school life, Ghost World stands out contrastively against the backdrop afforded by the tradition of superhero comics, for example. Far from possessing superhuman powers, Enid Coleslaw4 and Rebecca Doppelmeyer struggle with familial and romantic relationships, resist the stereotypes their peers try to impose on them, and are bought face to face, on more than one occasion, with the fragility and tenuousness of their own friendship. In this way, closer in spirit to the female Bildungsroman than to action-adventure narratives, Ghost World, which was originally published as installments in the underground comics tradition and subsequently assembled into a novel, overlays a graphic format on content that helped extend the scope and range of comics storytelling generally: the acquisition of gendered identities, the aftermath of fractured families, the attempt to find a path to adulthood that is not tantamount to conformism, and so on.

The novel as a whole traces events leading up to the divergent life-courses of the two main characters, caused in part by Rebecca’s willingness to accommodate to dominant social scripts versus Enid’s resistance to those same scripts. Zwigoff’s film adaptation of the novel accentuates even more the increasingly divergent paths of the main characters. In the movie, Rebecca nags Enid to get a job so that they can get an apartment together and, in a moment suggesting incipient conformism on Rebecca’s part, expresses particular admiration for a foldout ironing board built into the wall of the apartment that she has leased.

Ghost World also examines more or less entrenched cultural expectations about male versus female roles – interrogated for example in the scene in which Enid and Josh (Enid and Seymour in the film version) visit an adult bookstore/sex toy shop and Enid openly mocks what is on offer there. Relatedly, the novel explores Enid’s and Rebecca’s difficulty in finding suitable or even tolerable romantic partners, the focus of Sequence B below. In Zwigoff’s 2001 film version, this difficulty helps explain why Enid gravitates toward Seymour, a character more than twice her age but similarly suspicious of dominant social norms and values – at least for most of the film.

Sequence A

Sequence B

Sequences C and D. These two sequences are part of the same chapter of Ghost World but are separated by intervening material not reproduced here.

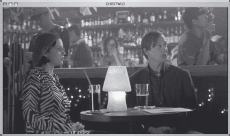

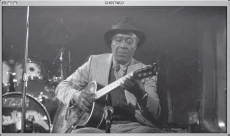

Screenshots from Terry Zwigoff ’s Film Adaptation of Ghost World (2001)

Screenshot 1 Just after Rebecca has said that the “blond guy... like gives me a total boner,” and Enid responds, “He’s like the biggest idiot of all time,” the person in question walks by and says “You guys up for some Reggae tonight?” Enid then points her thumb in his direction and gives Rebecca a “told-you-so” look.

Screenshot 2 At the bar where Seymour, frustrated that he can’t hear the blues musician whose playing he came to see, says, “I can’t believe these people. They could at least turn off their stupid sports game till he’s done playing.” In the middle background is the woman with whom Enid tries to fix Seymour up, but who seems as put off by Seymour’s lecture on ragtime versus blues as he is by her comment that the band Blues Hammer (see Screenshot 7) plays “authentic blues” and is “so great.”

Screenshot 3 The blues artist whose performance Seymour and Enid come to the bar to hear.

Screenshot 4 One of the patrons in the bar where Seymour complains about the “sports game” and the noise level that prevents him from hearing the blues guitarist who he hopes will autograph a rare copy of one of his albums.

Screenshot 5 Another patron in the bar. As Enid sizes up her surroundings, her glance falls on this person, who burps ostentatiously after taking a drink from his beer, as well as another male patron who stares lewdly at the waitress after he has tipped her, and a third in sunglasses that give him a somewhat menacing appearance (see Screenshot 6). Then Enid looks at Seymour sitting at the table with the female patron with whom he proves to have nothing in common.

Screenshot 6 Two other male patrons on whom Enid’s gaze falls as she takes stock of the men near her in the bar. (The waitress, having served beer to the patron on the right, moves away toward the camera in the foreground.)

Screenshot 6 Screenshot 7 The band Blues Hammer begins its first set, the lead singer/lead guitarist having started by shouting out over the microphone: “Alright, people. Are you ready to boogie? ’Cause we gonna play some authentic way down in the Delta blues. Get ready to rock your world!”