chapter three

Gifts from Japan

An apocryphal story, told in jest, says that when John Creech, the new Director of the U.S. National Arboretum, and Sylvester “Skip” March, the Arboretum’s Chief Horticulturist at the time, left for Tokyo in 1975 to receive Japan’s Bicentennial Gift, they took only two large, empty suitcases to pick up what they expected would be a few tiny trees. Instead, they were thrilled to find 50 trees waiting for them—one for each state in the U.S.—plus six viewing stones, then astonished to learn there would be three more bonsai added to the group. These additions were gifts from the Imperial family—Princess Chichibu, Prince Takamatsu and Emperor Hirohito himself. The trees and the viewing stones packed in their sturdy crates required an entire Pan Am 707 freighter to ship them from Tokyo to California. Two other planes flew them across the continental U.S., arriving in Baltimore, Maryland on March 31, 1975. The trees were unpacked and placed in a special facility for the year-plus quarantine period Creech had negotiated to make their importation possible.

Some bonsai from the Bicentennial Gift soak up the sun they need in the museum’s courtyard on a summer day, with koinobori flags flying, mementos of Children’s Day, and crapemyrtles at their peaks.

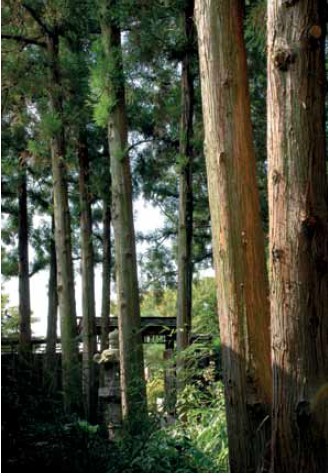

Inspired by entrances to Japanese temples and shrines, the Cryptomeria Walk provides a calming transition from the National Arboretum grounds to the museum’s display areas.

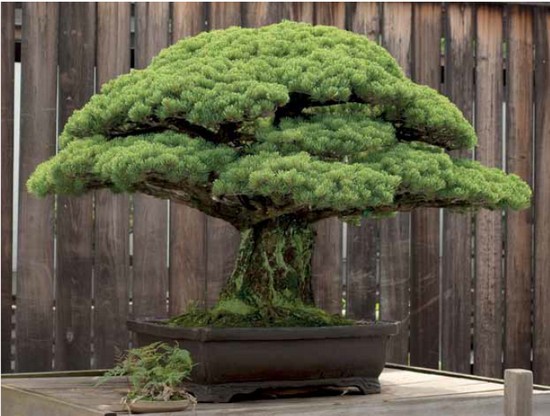

The Imperial Pine, a Japanese Red Pine (Pinus densiflora) in training since 1795, took pride of place as a gift from Emperor Hirohito (1901–1989). It was an unprecedented honor for the emperor to include a tree from the Imperial Collection in the gift to the United States. None had ever left Japan before. Fortunately, Creech and his colleagues realized what an exceptional tree they had received, and they made it possible for the tree to leave quarantine and go to the White House for a dinner on October 3, 1975 honoring Emperor Hirohito and Empress Nagako, hosted by President Gerald and First Lady Betty Ford.

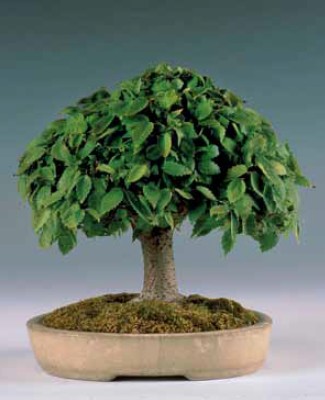

Princess Chichibu (1909–1995), the Emperor’s sister-in-law, wife of the Emperor Taishō’s second son, gave a tree from her personal collection—a Japanese Hemlock (Tsuga diversifolia). The daughter of a Japanese diplomat, Princess Chichibu was born Setsuko Matsudaira in London. Later, her father was named Ambassador to the United States and she graduated from Sidwell Friends School in Washington, D.C. In addition to her interest in bonsai, Princes Chichibu supported activities involving international good will, health, sports and scholarship, serving for many years as President of the Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association. The Japanese Hemlock is in the formal upright style and began training as a bonsai in a pot in 1926.

John Creech hosted Princess Chichibu when she visited her tree at the National Arboretum. He described the visit in The Bonsai Saga:

One other amusing event occurred in the spring of 1978 during the visit of Princess Chichibu, the Emperor’s [sister-in-law], who requested to see her tree and the pavilion.... Of course the State Department had them on a tight schedule, with an escort determined to keep the visit on track. They had almost completed their stroll through the pavilion, but just as they were about to leave, Princess Chichibu spotted a robin in a nest in the Emperor’s red pine tree. Well, I must tell you that the excitement was remarkable.... For a good half an hour, they photographed the robin in her nest and chatted excitedly about this wonderful event, much to the distress of their State Department guide [whose] schedule had just been destroyed.

The Imperial Pine, a Japanese Red Pine (Pinus densiflora), in training since 1795, was the first bonsai from the Japanese Imperial Collection to leave the country.

Thin bamboo rods provided shade in traditional Japanese style when the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum was new and the Imperial Pine was on public display.

Princess Chichibu, Emperor Hirohito’s sister-in-law, gave a Japanese Hemlock (Tsuga diversifolia), in training since 1926, from her collection as part of Japan’s Bicentennial Gift to the U.S.

Princess Chichibu visited her gift tree and other bonsai from Japan at the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum in 1978.

During her visit to the museum, Princess Chichibu was delighted to find a robin feeding her hungry babies in her nest in the Japanese Imperial Pine.

Prince Takamatsu, brother of Emperor Hirohito, added this Trident Maple (Acer buergerianum), in training since 1895, to Japan’s Bicentennial Gift to America. Its dramatic shape, with a distinctive arching trunk, and changing foliage delight visitors in every season.

Before he became emperor, Prince Hirohito was photographed in 1921 with his brothers: left to right, the future emperor, Prince Mikasa, Prince Takamatsu and Prince Chichibu.

The third tree with a Japanese imperial connection is a Trident Maple (Acer buergerianum), which was trained as a bonsai from a seedling. It was a gift from Prince Takamatsu (1905–1987), the third son of Emperor Taishō. Prince Takamatsu served in Japan’s navy through World War II, after which he played largely ceremonial roles in a variety of activities, ranging from international relations, health and welfare to fine arts and sports. The Prince’s tree has a quiet nobility and is treasured for its distinctive curving trunk, its artful roots and its dramatic fall foliage. It is believed to have been in training since 1895.

The other 50 trees assembled by the Nippon Bonsai Association may not have had imperial pedigrees, but each was specially selected from private collections to represent Japan, and some had amazing stories of their own.

The oldest tree in the gift and at the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum today is the Yamaki pine, a Japanese White Pine (Pinus parviflora ‘Miyajima’), which has been in training since 1625. Its designation as ‘Miyajima’ shows it is from an island not far from Hiroshima, famous for its torii gate and the Itsukushima Shrine. While the tree was known to be ancient when it arrived in American quarantine in 1975, no one knew its full story until 2001 when grandsons of the bonsai master Masaru Yamaki, who had given it, visited the tree at the U.S. National Arboretum. The young men explained that their family had operated a commercial bonsai nursery in Hiroshima for several generations. On August 6, 1945, the atomic bomb dropped less than two miles from their home, blowing out all of the glass windows. Each family member was cut though miraculously no one suffered any permanent injuries. The Yamaki pine and others in the nursery were protected from the blast by a wall, and its inclusion added a profound and poignant note to the Bicentennial Gift.

Another Japanese White Pine (Pinus parviflora ‘Miyajima’) arrived after the Bicentennial Gift. The distinctive slant of the trunk is balanced by the design of its branches and foliage. It was given to the museum by the late Daizo Iwasaki, a noted bonsai collector in Japan.

A tree treasured by the Japanese is the cryptomeria or Sugi (Cryptomeria japonica). It is often called a Japanese cedar though it is not a true cedar. In Japan, some consider it the national tree because it is often planted around temples and shrines, marking the passage from the “daily” world to a “sacred” space. At the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum, cryptomeria line the entrance walk, creating a transitional space into the museum’s pavilion area, similar to their use in Japan. Its evergreen quality is perceived as a symbol of longevity and strength. In addition to its landscape use, Cryptomeria is also used for lumber and for a variety of crafted products. The bonsai Cryptomeria forest planting in the Bicentennial Gift echoes the “grown up” versions lining the entrance walk and was a gift of a former Prime Minister of Japan, Eisaku Satō.

A Trident Maple (Acer buergerianum), in training since 1856, has a different shape from Prince Takamatsu’s and was included in the Bicentennial Gift. It was also grown from a seedling but this one conveys majesty in a different way. It has a formal upright-style trunk tapering to an apex with flaring surface roots, creating the illusion of great age and magnificence.

Following his state visit with President Clinton in 1999, Japanese Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi (1937–2000) gave the museum a gift of seven bonsai. One is a 9-inch-high Japanese Zelkova (Zelkova serrata) that has been in training since 1984 and will never grow any larger. Dr. Thomas Elias, then Director of the U.S. National Arboretum, played an important role in the gift, ensuring the museum collections’ continued pre-eminence among public bonsai collections in North America.

The Yamaki Pine, a Japanese White Pine (Pinus parviflora ‘Miyajima’), in training since 1625, appears to be even older than it is because of the deep fissures in its trunk.

The Yamaki Pine was among the bonsai in the Bicentennial Gift admired by visitors to the National Bonsai Association’s headquarters in Tokyo’s Ueno Park before being crated for shipment to the U.S.

Descendants of donor Masaru Yamaki, including Shigeru Yamaki shown here, have visited the tree in recent years, keeping alive its remarkable story of surviving the bombing of Hiroshima.

About 35 of the original trees from Japan’s Bicentennial Gift survive today, ably fulfilling their role as international ambassadors. Others have joined them in the intervening decades and others will surely be added in the future, ensuring that the bonsai’s expression of the power of beauty, perseverance and peace will abide far into the future.

Cryptomeria trees, considered the national tree of Japan, grow inside the entrance of the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum.

A forest planting of Japanese cedars (Cryptomeria japonica), in training since 1905, was contributed to the Bicentennial Gift by former Prime Minister Eisaku Satō.

A photographer captures the glowing fall foliage of three Japanese bonsai: left to right, a Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), a Zelkova (Zelkova serrata) and a Trident Maple (Acer buergerianum).

Although Zelkovas can surpass 50 feet in nature, as bonsai they are only a few feet tall, or, if a shohin bonsai like this one, just a few inches high.

A slant-style Japanese White Pine (Pinus parviflora ‘Miyajima’), in training since 1879, was a gift of Daizo Iwasaki to the national collection in 2004.

An informal upright Trident Maple (Acer buergerianum), in training since 1856, seems much older than it really is thanks to its strongly tapered trunk and wide-spreading surface roots.

SPOTLIGHT ON Yuji Yoshimura

While the Bicentennial Gift from Japan provided the impetus toward the establishment of the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum, the trees in that collection were not the first bonsai to arrive at the U.S. National Arboretum. Dr. Creech met and befriended Yuji Yoshimura during his plant explorations in Japan and was instrumental in encouraging Yoshimura’s immigration to the United States for a fellowship at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden in 1958, where he cared for their bonsai collection.

Dr. Creech invited Yoshimura to Washington in 1973 to encourage local enthusiasm for bonsai. At a meeting of the Potomac Bonsai Association, Yoshimura stunned the audience with his drastic pruning of a Kingsville Dwarf Boxwood (Buxus microphylla ‘Compacta’). One attendee expressed her shock at the skeletal form, saying, “Oh dear. He’s killing the plant!” Today, more than forty years later, museum visitors can enjoy the results of Yoshimura’s masterful technique that established a basic structure for the future training of the boxwood as a bonsai.

Yuji Yoshimura was an animated and committed teacher, working to encourage enthusiasm for bonsai in the U.S. He often used his students’ bonsai as examples.

Dr. Creech and Yuji Yoshimura considering a Kingsville Dwarf Boxwood (Buxus microphylla ‘Compacta’), a plant prized for its small leaves and slow growth.

On July 9, 1976, during the dedication ceremony, Yuji Yoshimura posed with the Imperial Pine and a Chrysanthemum Stone, both part of Japan’s Bicentennial Gift to the U.S.

Crystals form the flower shapes seen in this Chrysanthemum Stone from Neodani in Gifu Prefecture, Japan, which was polished by a river’s waters, not by hand.

Created by his father Tohiji Yoshimura in 1930, this Crapemyrtle (Lagerstroemia indica) represented a family legacy entrusted to the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum by Yuji Yoshimura in 1990.

Yoshimura’s commitment to teaching the principles of classic bonsai techniques and viewing stone principles that he had learned from his father Toshiji Yoshimura was comprehensive. He taught extensively from his home base in Westchester County as well as traveling worldwide. Notably, he preferred to assist his students in creating bonsai rather than establish a collection of his own. He published many articles and co-authored two books, The Japanese Art of Miniature Trees and Landscapes in 1957, and The Japanese Art of Stone Appreciation: Suiseki and Its Uses with Bonsai in 1984.

Less than two years after Yoshimura’s virtuoso performance in Washington, his living work of art would be joined by 53 other trees and six viewing stones from Japan, leading to the creation of the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum.